Clinical decision-making

Introduction

Appropriate clinical decision-making is an intrinsic and frequently complex process at the heart of clinical practice (Hardy & Smith 2008) with some situations being more complex than others as they involve more unknowns and uncertainties (Cioffi & Markham 1997, Cioffi 1998). Decisions should be based on best practice and have an evidence base to them, this is essential to optimize outcomes for patients, improve clinical practice, achieve cost-effective nursing care and ensure accountability and transparency in decision-making (Canadian Nurses Association 2002). This process should not, therefore, be underestimated. The assessment, evaluation and subsequent changes made to a patient’s care are intrinsically involved. The assessment process and the effective use of assessment information through appropriate decision-making are essential to improve outcomes of care (Aitken 2003). Within the patient assessment the nurse should, through a systematic approach, support clinical findings with hard scientific fact.

Requesting tests and the analysis of data completes this process. Simply put, if a nurse omits to request a relevant test there will be no scientific evidence to support the initial working diagnosis. Bochund & Calandra (2003) identified that requesting relevant tests during the initial assessment significantly reduced morbidity and mortality rates.

In order to understand the processes involved in clinical decision-making it is essential to consider the context in which decision-making activities are being performed. The ED was the portal for over 12.3 million annual visits in England in 2007–8, of which 20 % required hospital admission (Health and Social Care Information Centre 2009). These millions of patients attend with any number of clinical presentations and complaints requiring the assistance of every medical specialty. The role of the emergency nurse is unique in this respect, as in no other clinical setting is the nurse called upon to assess and identify the needs of such a wide range of potential patient conditions.

Initial assessment

The ED is the interface between patients and emergency care. Within this setting a patient’s first contact with a healthcare professional will usually be with a nurse; the process of initial assessment. Nursing triage is a dynamic decision-making process that will prioritize an individual’s need for treatment on arrival to an ED and is an essential skill in emergency nursing (Smith 2012). An efficient triage system aims to identify and expedite time-critical treatment for patients with life-threatening conditions, and ensure every patient requiring emergency treatment is prioritized according to their clinical need. The ethos of triage systems relates to the ability of a professional to detect critical illness, which has to be balanced with resource implications of ‘over triage’ i.e., a triage category of higher acuity is allocated. A decision that underestimates a person’s level of clinical urgency may delay time-critical interventions; furthermore, prolonged triage processes may contribute to adverse patient outcomes (Travers 1999, Dahlen et al. 2012).

In this context, the triage nurse’s ability to take an accurate patient history, conduct a brief physical assessment, and rapidly determine clinical urgency are crucial to the provision of safe and efficient emergency care (Travers 1999). These responsibilities require triage nurses to justify their clinical decisions with evidence from clinical research, and to be accountable for decisions they make within the clinical environment. The legal significance of undertaking an assessment relates to whether the nurse has sufficient knowledge to perform the assessment competently: if the patient care is compromised a tort of negligence could be issued (Dimond 2004).

It has been identified that many factors impact on the nurse’s ability to make accurate decisions; for example, an unpredictable workload, poor professional continuity in relation to communication, and inexperience of the initial nursing assessor, or subsequent nursing staff (Tippins 2005). This has been exacerbated by demographic changes, such as an ageing population and the subsequent associated chronic pathologies, which have placed an enormous strain on primary care services (Dolan & Holt 2007), and secondly on the subjective clinical decision-making of the triage nurse (Cooke & Jinks 1999). If there is a failure to recognize deterioration in a patient’s condition and intervention is delayed, the condition of these patients can potentially become critical. The care provided during the ED stay for critically ill patients has been shown to significantly impact on the progression of organ failure and mortality (Rivers et al. 2002, Church 2003). It is, therefore, essential that the care provided in the ED reflects the severity of the condition of the patient, the focal point being that accurate and dynamic patient assessment is imperative.

Continued assessment

The continued assessment and monitoring of patients is imperative in order that subtle changes in their condition can be recognized and intervention instigated and evaluated. Physiological monitoring and the identification of deterioration in patients’ conditions are an essential part of the role of the ED nurse; however, it remains uncertain whether this translates into the clinical setting. Patients who are critically ill are more likely to be recognized as such at initial assessment than if they deteriorate following that assessment (Cooke & Jinks 1999, Tippins 2005). For example, a patient who presents to the ED with a blood pressure of 89/38, pulse of 127 and respiratory rate of 31 is likely to be allocated a high clinical priority. In contrast, if the same patient presented an hour earlier with a blood pressure of 109/72, pulse of 98 and a respiratory rate of 24, they may not be allocated as high a priority on initial assessment, and their subsequent deterioration an hour later (after their first set of observations) will not necessarily result in a reallocation of priority (Cooke & Jinks 1999, Tippins 2005).

This phenomenon can be explained by a failure in the reassessment process and priority reallocation necessary to reflect the patient’s changing physical condition. The introduction of education programmes, such as the Acute Life-threatening Events, Recognition and Treatment (ALERT) course, and tools such as the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), may be of benefit to assist staff in identifying patients who are deteriorating or are at risk of doing so. At the very least they ensure a structured approach to patient assessment and the regular and accurate recording of basic physiological observations, a crucial first step in recognizing patients at risk. Other possible explanations for the delay in recognizing patient deterioration could be external factors such as workload pressures, breakdown of communication, and lack of senior input (National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death 2009). The inexperience of staff in dealing with critically ill patients, the impact of teamwork and complacency when faced with certain conditions have also been shown to have an impact on clinical decision-making and, therefore, the care of critically ill patients (Bakalis & Watson 2005, Tippins 2005).

Clinical decision-making

Decision-making can be divided into three categories: normative, descriptive and prescriptive approaches. Each of these categories has its own unique features, ideas and terminology. Normative decisions can be described as assuming the decision-maker is logical, rational and concentrates on how decisions are made in the ideal world. In comparison, descriptive theories attempt to describe how decisions are made and so are more concerned with the process of decision-making and how individuals reach that decision. Prescriptive theories try to improve the individual’s decisions by looking at how decisions are made by understanding how a decision is formulated (Thompson & Downing 2009). Of these different approaches to decision-making, prescriptive and descriptive approaches are the most common approaches used by practitioners (Cioffi & Markham 1997, Lurie 2012).

Clinical decision-making can be defined as the process nurses use to gather patient information, evaluate that information and make a judgement which results in the provision of patient care (White et al. 1992). This process involves collecting information with the use of both scientific and intuitive assessment skills. This information is then interpreted through the use of knowledge and past experiences (Cioffi 2000a, Evans 2005, Evans & Tippins 2007).

There are many theories on how to teach these essential and dynamic skills; however, learning or the acquisition of new knowledge does not necessarily guarantee the clinical application of expert practice (Tippett 2004) or critical thinking. Many theories of teaching and learning the art of critical thinking and expert clinical decision-making exist; behaviourist, cognitive, and humanistic being the commonly used three (Sheehy & McCarthy 1998). The behaviourist theory relates to reactionary learning whereby the learning occurs when an unmet need causes the learner to embrace the learning process; unfortunately the inclination to learn is often stimulated due to the learner feeling inadequate due to uncertainty and a lack of confidence. The cognitive theory relates to the interaction between the learner and their immediate environment, i.e., learning through experience and professional stimulation. The humanistic theory relates to adult-based learning where the focus is clearly on the learner to ascertain new knowledge through the process of self-discovery. A teacher who has understanding will present organized subject matter that is relevant to the learner’s need and will, therefore, propagate learning. The expert practitioner perceives the situation as a whole, uses past concrete situations as paradigms and moves to the accurate region of the problem without wasteful consideration of a large number of irrelevant options.

Nursing process

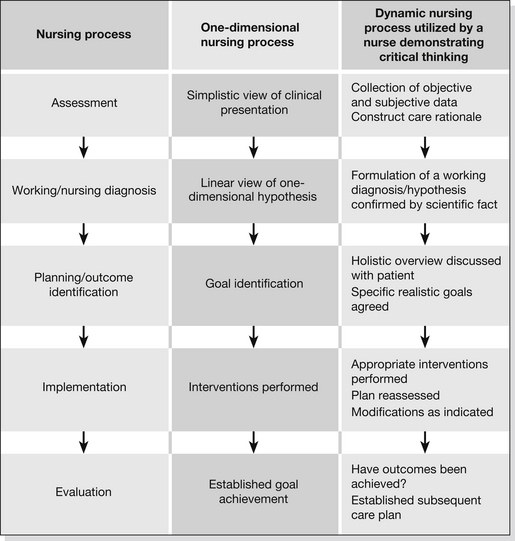

The nursing process is a tool used by nurses to assist with decision-making and to predict and evaluate the results of nursing actions (Reeves & Paul 2002). The deliberate intellectual activity of the nursing process guides the professional practice of nursing in providing care in a systematic manner. The nursing process has evolved over recent years to incorporate five or six phases or stages (Box 37.1 and Fig. 37.1) (Reeves & Paul 2002, Ryan & Tatum 2012).

Movement between these phases is unusually linear; there is free movement among the phases during clinical practice. Once an assessment begins the nurse should begin to formulate diagnoses and eliminate others. As more information is gathered, through physical and technological findings, the practitioner should begin to narrow the possibilities. The worst possible diagnosis should be paramount in the practitioner’s hypotheses, as this must be addressed and eliminated before moving on. By using a systematic approach patient problems can be identified and acted upon in the most effective way to ensure the best possible outcome for the patient. Examples of a systematic approach are those adopted by the Resuscitation Council (2011) on the Advanced Life Support (ALS) course with the ABC mnemonic (airway, breathing and circulation) and ABCDE (airway, breathing, circulation, disability and environment), taught by the Royal College of Surgeons (2005) and American College of Surgeons (2008) in the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) course.

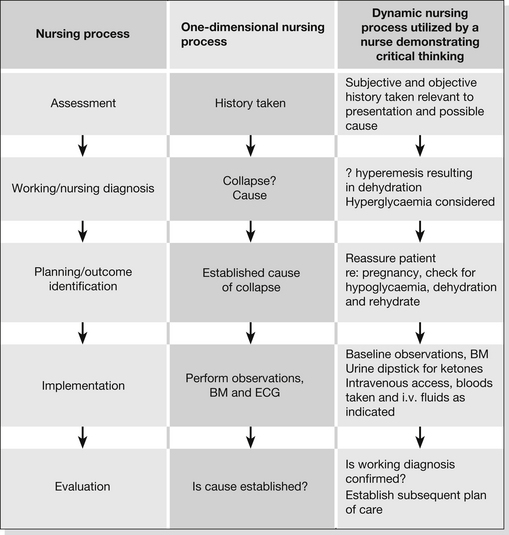

In order to demonstrate the nursing process a clinical scenario will be presented and discussed to demonstrate the practice from both a unilateral and a critical thinking perspective (Box 37.2 and Fig. 37.2).

Figure 37.2 The nursing process applied to scenario 1.

The nurse assessing the patient in a one-dimensional way will focus only on the patient’s presenting complaint, and in this case attempt to establish a cause for the collapse. The nurse demonstrating critical thinking, however, will take into account all available information gained from the assessment and utilize it in order to establish a working diagnosis. In this example the one-dimensional process disregards the fact that the patient is pregnant. The dynamic model will take this information into account and process it along with all other available information, considering the bigger picture. With the use of critical thinking a working diagnosis/hypothesis will be formulated: hyperemesis; and appropriate scientific fact sought to either confirm or refute it. When the evaluation phase is reached, the nurse in the one-dimensional example may not have established a cause for the patient’s collapse and, as a result, may have to go back to previous phases. In contrast, the critical thinker may have confirmed a working diagnosis, established a subsequent care plan and moved on.

The current demands placed on clinicians require the ED practitioner to be proactive and dynamic in their utilization of the nursing process. They need to know which stages can be safely omitted, combined or delayed, and also which situations warrant a rigorous, comprehensive approach (Alfaro-LeFevre 2004). There is, therefore, a clear need to implement a tool or structure to the diagnostic process directly aimed at ED nurses to facilitate the application of critical thinking. Novice practitioners frequently require a clear-cut approach to patient assessment; this can be achieved by applying the DEAD mnemonic as an aide-memoire or self-questioning analytical tool. This approach is outlined in Box 37.3 (Evan & Tippins 2007).

Critical thinking

The clinical scenarios outlined in Box 37.4 will be discussed to demonstrate the critical thinking and clinical decision-making involved in the initial and continuing assessment process.

Data The data the initial assessor will require are based on the patient’s presenting complaint and medical history. The initial nursing or working diagnosis in this case would be an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The nurse should be quick to ascertain the nature of the patient’s pulse. A radial pulse can reflect the onset of physiological shock or the presence of life-threatening arrhythmias, including complete heart block, atrial fibrillation and tachycardias. The nursing diagnosis and need for immediate intervention can be either validated or negated by the recording of an ECG which would reflect the pathological changes associated with acute ST segment elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI). The data recording at this point should include the requesting of blood tests, particularly as other co-existing pathologies may be exacerbating this presentation, such as anaemia.

Emotions The assessor’s gut reaction in this case should be to consider the working diagnosis of STEMI. Comparing the current presentation with previously experienced situations should alert the nurse to the potential severity of the condition, the process of pattern recognition and experiential learning (Cioffi 2001, Muir 2004, Tippins 2005).

Advantages The advantages involved in this situation would be an early door to treatment time, which has been shown to dramatically improve morbidity and mortality rates. The rapid diagnosis and treatment of life-threatening pathologies such as ACS is essential (Department of Health 2000a).

Disadvantages (differential diagnosis). The priority in this case is to confirm or dispel STEMI. The assessor also needs to consider other possible diagnoses, for example a dissecting aneurysm, which would be a contraindication to therapy. This possibility would result in the assessor returning to the data collection phase of the process in order to negate a potential aneurysm via further data collection.

Past experiences

In decision-making involving complexity, studies have shown that decision-making strategies are dependent on the individual’s experiences (Cioffi 1998, Tippins 2005). Nurses use past experiences to assist in decision-making by comparing the current situation to previously experienced situations held in their memory (pattern recognition). This can manifest itself in a variety of forms, including recognizing a similarity between the present patient’s condition/situation and a group of patients previously cared for with this presenting condition/situation, to describing quite specifically identified characteristics (Grossman & Wheeler 1997, Cioffi 1998, 2001). For example, a nurse who has previously cared for a patient with meningococcal meningitis may identify a future patient with the condition by recognizing a specific sign or symptom witnessed in the first instance, such as the petechial rash. Benner (1984) discusses the differences between a novice and an expert and proposes that they can be attributed to the know-how that is acquired through experience.

Furthermore, past experiences with patients’ symptoms and their probable outcomes is a factor that will determine the action a nurse will take in response to a patient’s presentation (Radwin 1998). A recommendation for practice, therefore, must be to provide teaching to staff on conditions and situations common, but infrequently experienced, within the ED. This could facilitate the development of pattern-recognition skills, and improve response to critical care events. This could also address the retention of knowledge and skills gained in continuing professional development courses (Department of Health 2000b).

The use of reflection to assist in personal debriefing has an impact on the management of future practices when patients present with similar conditions (Evans 2005, Tippins 2005). By reflecting both on and in practice, with the use of critical thinking, best outcomes can be hypothetically discussed. This will result in modifications in an individual’s clinical practice, and ultimately a positive impact on the care of future patients. Reflective practice has become an integral part of daily nursing life (Johns & Freshwater 1998). The need to reflect, critically analyse, develop and, where possible, improve is the constant aim of the nursing profession in the twenty-first century.

Intuition

Generally it is accepted that hard facts or science are the base from which nursing practice is delivered, and that intuition or logic do not directly influence clinical practice. In contrast the reality is very different, the rationalist paradigm of knowledge is logic, and the empiricist paradigm is science. Interestingly, empirical knowledge is less certain than logic; it is tentative, responsive to new evidence and better research, and always open to re-testing. The primary aim of applying theory in practice is to improve the patient’s quality of care. Experts are able to generate better hypotheses due to a larger database of knowledge from which to pull ideas. This expert knowledge may also be assembled from intuition. Robinson (2000) identifies that clinical decision-making is the foundation of how an expert clinician can utilize their experientially based knowledge base to draw conclusions when assessing each new encounter.

Nurses’ experience plays a major role in the development of critical observations, skills and subsequent intuition (Benner & Tanner 1987). When confronted with situations in which clinical judgements are characteristically uncertain, the nurse will rely upon the use of intuition to assist with their clinical decision-making (Benner & Tanner 1987). It has been argued that intuition actually accelerates the analytical process that leads to a nursing intervention (King & Appleton 1997). The use of intuition and systematic processes of decision-making has predominantly been believed to have occurred only in the more experienced and expert nurses (Benner & Tanner 1987, Watkins 1998, Rew 2000). Intuitive aspects of decision-making may, however, commence in nurses at an early point in their career and strengthen or lessen with time depending on their experiences and developing expertise (Sirkka et al. 1998, King & MacLeod Clark 2002).

Emergency nurses often have to deal with patients with life-threatening conditions, and sometimes reach a critical stage of perceiving a change in a patient’s condition signifying that the patient may soon deteriorate. This use of intuitive judgement has been shown to be useful in the recognition of patient deterioration (Cioffi & Markham 1997, Cioffi 2000b, Tippins 2005, Harties et al. 2011). When used to identify deterioration this feeling is associated with knowing the patient (Cioffi 2000b), for which continuity of care is necessary (Grossman & Wheeler 1997).

Conclusion

The ultimate aim of emergency education is learning how to apply knowledge and understanding within the clinical setting. In order to achieve satisfactory outcomes the nurse must use elements from both the rationalist and empirical paradigms. The characteristics associated with advanced nursing practice centre on the practitioner utilizing the process of lateral thinking. Experts within the field of clinical decision-making suggest that in the absence of critical thinking, change and subsequent progress within the nursing profession would not have occurred. The ability of the nurse to reflect upon their role within the assessment process enables them to develop key analytical skills, which are essential within the role of emergency practitioners. Once the practitioner is able to demonstrate critical thinking they are able to construct more in-depth hypotheses. Emergency nurses play a pivotal role within the patient’s journey by instigating the plan of care through the validation of the working diagnosis or hypothesis. Their role is, therefore, unique and paramount to the patient’s subsequent care and clinical outcome.

References

Aitken, L.M. Critical care nurses’ use of decision-making strategies. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 12, 2003. [476–183].

Alfaro-LeFevre, R. Critical Thinking and Clinical Judgment: A practical approach. Philadelphia: Elsevier Science; 2004.

American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support, eighth ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2008.

Bakalis, N.A., Watson, R. Nurses’ decision-making in clinical practice. Nursing Standard. 2005;19(23):33–39.

Benner, P. From novice to expert: Excellence and power in Clinical Nursing Practice. California: Addison-Wesley Publications; 1984.

Benner, P., Tanner, C. Clinical judgment: how expert nurses use intuition. American Journal of Nursing. 1987;87:23–31.

Bochund, P.Y., Calandra, T. Science, medicine and the future: Pathogenesis of sepsis: new concepts and implications for future treatment. British Medical Journal. 2003;326:262–266.

Canadian Nurses Association. Evidence-Based Decision-Making and Nursing Practice. Ottawa: Canadian Nurses Association; 2002.

Church, A. Critical care and emergency medicine. Critical Care Clinics. 2003;19(2):271–278.

Cioffi, J. Decision making by emergency nurses in triage assessment. Accident and Emergency Nursing. 1998;6:184–191.

Cioffi, J. Recognition of patients who require emergency assistance: a descriptive study. Heart and Lung. 2000;29(4):262–268.

Cioffi, J. Nurses’ experiences of making decisions to call emergency assistance to their patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;32(1):108–114.

Cioffi, J. A study of the use of past experiences in clinical decision making in emergency situations. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2001;38:591–599.

Cioffi, J., Markham, R. Clinical decision making: managing case complexity. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25:265–272.

Cooke, M.W., Jinks, S. Does the Manchester triage system detect the critically ill? Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine. 1999;16:179–181.

Dahlen, I., Westin, L., Adolfsson, A. Experience of being a low priority patient during waiting time at an emergency department. Psychology Research and Behaviour Management. 2012;5:1–9.

Department of Health. National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease. London: Department of Health; 2000.

Department of Health. Comprehensive Critical Care – A Review of Adult Critical Care Services. London: Department of Health; 2000.

Dimond, B. Legal Aspects of Nursing, fourth ed. London: Longman; 2004.

Dolan, B., Holt, L. Preface. In Dolan B., Holt L., eds.: Accident and Emergency Theory into Practice, second ed, London: Baillière Tindall, 2007.

Evans, C. Clinical decision making theories: patient assessment in A&E. Emergency Nurse. 2005;13(5):16–19.

Evans, C., Tippins, E. Foundations of Emergency Care. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

Grossman, S.C., Wheeler, K. Predicting patients’ deterioration and recovery. Clinical Nursing Research. 1997;6:45–58.

Hardy, D., Smith, B. Decision Making in Clinical Practice. British Journal of Anaesthetic & Recovery Nursing. 2008;9(1):19–21.

Harties, C., Morgenthaler, B., Kugler, C., et al. Intuitive decision making in emergency medicine: An explorative study. In: Sinclair M., ed. Handbook of Intuition Research. London: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2011.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Accident and Emergency Statistics in England. Leeds: NHS Information Centre; 2009.

Johns, C., Freshwater, D. Transforming Nursing Through Reflective Practice. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1998.

King, L., Appleton, J. Intuition: a critical review of the research and rhetoric. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;26:194–202.

King, L., MacLeod Clark, J. Intuition and the development of expertise in surgical ward and intensive care nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;37(4):322–329.

Lurie, S.J. History and practice of competency based assessment. Medical Education. 2012;46(1):49–57.

Muir, N. Clinical decision-making: theory and practice. Nursing Standard. 2004;18(36):47–52.

National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Caring to the End? A review of the care of patients who died in hospital within four days of admission. London: NCEPOD; 2009.

Radwin, L.E. Empirically generated attributes of experience in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;28:590–595.

Reeves, J.S., Paul, C. Nursing theory in clinical practice. In: George J.B., ed. Nursing Theories: The Base for Professional Nursing Practice. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2002.

Resuscitation Council. Advanced Life Support Course Provider Manual, sixth ed. London: Resuscitation Council (UK); 2011.

Rew, L. Acknowledging intuition in clinical decision-making. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2000;18:94–108.

Rivers, E., Nguyen, H., Bryant, M.D., et al. Critical care and emergency medicine. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2002;8(6):600–606.

Robinson, D. Clinical Decision-Making: A Case Study Approach, second ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2000.

Royal College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support. London: Royal College of Surgeons; 2005.

Ryan, C., Tatumm, K. Objective measurement of critical-thinking ability in registered nurse applicants. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2012;42(2):89–94.

Sheehy, C., McCarthy, M. Advanced Practice Nursing Emphasizing Common Roles. Philadelphia: Davis Company; 1998.

Sirkka, L., Salantera, S., Callister, L.C., et al. Decision-making of nurses practising in intensive care in Canada, Finland, Northern Ireland, Switzerland and the United States. Heart and Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care. 1998;27:133–142.

Smith, A. Using a theory to understand triage decision making. International Emergency Nursing. 20, 2012.

Thompson, C., Downing, D. Essential Clinical Decision Making and Clinical Judgement for Nurses. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

Tippett, J. Nurses acquisition and retention of knowledge after trauma training. Accident and Emergency Nursing. 2004;12:39–46.

Tippins, E. How emergency department nurses identify and respond to critical illness. Emergency Nurse. 2005;13(3):24–33.

Travers, D. Triage: how long does it take? How long should it take? Journal of Emergency Nursing. 1999;25:238–241.

Watkins, M.P. Decision-making phenomena described by expert nurses working in urban community health settings. Journal of Professional Nursing. 1998;14:22–33.

White, J., Nativo, D.G., Kobert, S.N., et al. Content and process in clinical decision making by nurse practitioners. Image. 1992;24:153–158.