Chapter 4 Clinical Assessment of the Elbow

Physical examination

General examination of the elbow

Inspection

Inspection requires appropriate exposure of the cervical spine, shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand. When assessing the skin, notable features include skin integrity, quality, pigmentation, scars or incisions, fistulas or sinuses, masses or ecchymosis. As an example, depigmentation may occur as a result of prior corticosteroid injections (Fig. 4.1).

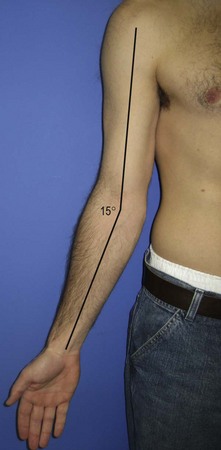

Assessment of the patient’s carrying angle (Fig. 4.2) is also important and should be compared to the contralateral elbow. It is measured with the arm adducted and externally rotated, the elbow extended, and the forearm supinated. The carrying angle is the angle formed by the long axis of both the arm and the forearm. Although there is with some dispute amongst authors as to whether differences exist between the sexes,1–3 the normal ranges for men and women are 10–15° of valgus. Some patients may demonstrate excessive cubitus valgus or cubitus varus as a result of previous trauma or disorders of physeal growth. Some overhead-throwing athletes have an increased physiological valgus carrying angle.4

Palpation

A systematic approach to palpation will ensure that no significant abnormality is missed. Table 4.1 provides a list of structures to include in the examination. On the lateral aspect of the elbow, the key anatomic landmarks to palpate are the lateral epicondyle, lateral collateral ligament, radial head, lateral soft spot (Fig. 4.3), crista supinatoris and the common extensors (Fig. 4.4).

Table 4.1 Structures to include during palpation of the elbow joint

| Lateral |

On the medial aspect of the elbow, the key structures are the medial epicondyle, the ulnar nerve (Fig. 4.5), the sublime tubercle and the flexor–pronator group. The latter is best visualized when placed under tension (Fig. 4.6).

Anteriorly, the coronoid (Fig. 4.7) is important to palpate, as is the distal biceps tendon (Fig. 4.8).

Motion

Determining the range of motion of the elbow is incomplete without an assessment of the range of motion of the cervical spine, shoulder and wrist. The use of a goniometer is helpful in collecting reproducible data that may be used for comparison in subsequent visits. The standard deviation of error for a single observer using a manual goniometer is 3.7° for any joint. With respect to the elbow, the standard deviation of measurement error varies with each motion. The following are the reported standard deviations of measurement error for elbow extension, flexion, pronation and supination, respectively: 2.7°, 4.9°, 5.3° and 4.0°. Given the imprecision of these measurements, Boone and Azen recommend that a single observer should perform repetitive measurements over successive encounters.5

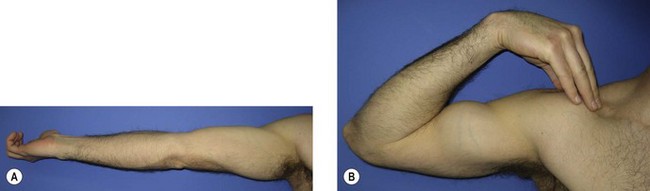

Documenting the range of motion with standardized methods is important to ensure consistency of information across clinic visits and providers. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons defined these standards in 1965.6 In 1979, Boone and Azen studied normal elbow range of motion in 109 normal subjects. In patients older than 19 years, the flexion–extension arc measured from 0° (full extension) to 140° (full flexion) (Fig. 4.9). Flexion was significantly greater (145°) in subjects younger than 19 years.5 Patients with some generalized ligamentous laxity may demonstrate hyperextension of the elbow, and this should be indicated with negative values (e.g. −10°). The functional arc of motion, allowing for most activities of daily living, is 30–130°.7

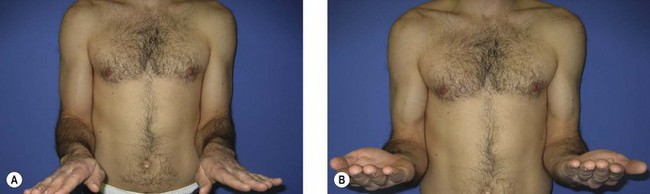

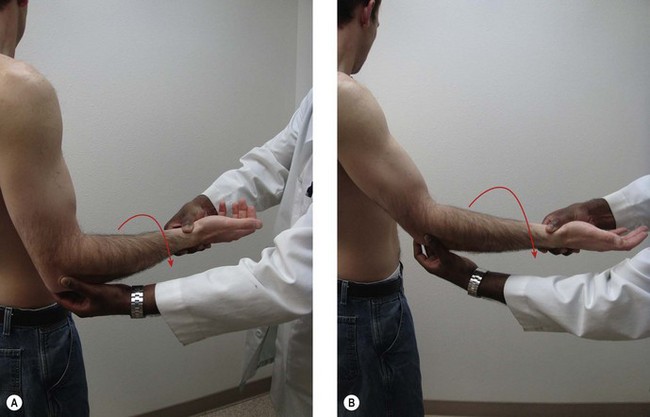

In a normal examination, most patients should achieve approximately 75° of pronation and 82° of supination (Fig. 4.10).5 Although it may appear that patients achieve 90° of rotation when observing the final hand position, as much as 15° of rotation is generated through the carpus and does not represent isolated forearm rotation. The functional arc of motion for forearm rotation is 50° of pronation to 50° of supination.7 It is important when pronation and supination are being measured that the patient’s elbow is flexed to 90° and at their side, since many patients will abduct or adduct the shoulder to compensate for loss of forearm rotation.

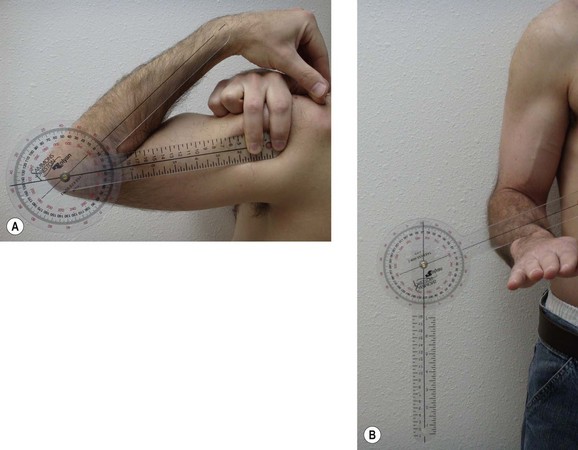

When using the goniometer to measure angles, consistent surface landmarks should be used to ensure that the arms of the goniometer are parallel to the humeral and ulna diaphyses. In muscular or overweight patients, it can be difficult to palpate the humeral shaft and it is better to use the anterolateral corner of the acromion as a reproducible landmark as it represents the approximate location of the humeral shaft. The hinge of the goniometer is placed at the rotational axis of the patient’s elbow, which is approximated by the lateral epicondyle. The distal arm of the goniometer is aligned with the subcutaneous border of the ulna. This is usually easy to see and palpate regardless of the patient’s body habitus. Flexion and extension should be measured with the forearm in supination (Fig. 4.11A). Measuring forearm pronation and supination should be done with the elbow at the patient’s side and in 90° of flexion. The goniometer arm should be placed parallel to the plane of the volar or dorsal aspect of the distal radioulnar joint and the other arm directed either downward with gravity (perpendicular to the floor) or upward (perpendicular to the ceiling) (Fig. 4.11B).

Neurological

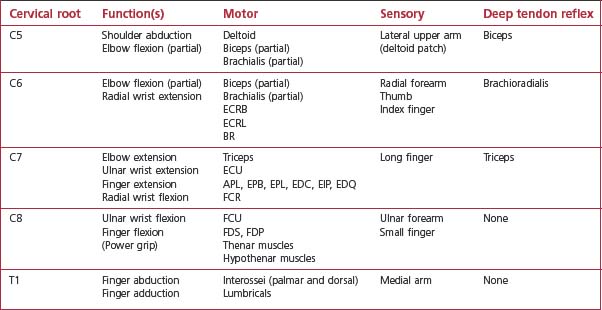

A complete neurological examination of the upper extremity should be conducted. This includes cervical roots C5–T1, the brachial plexus and the peripheral nerves. The accompanying tables are provided to guide in the examination of individual cervical roots (Table 4.2), as well as the individual peripheral nerves (Table 4.3).

| Axillary |

An important part of the neurological examination is an assessment of strength. This is done with the patient’s elbow flexed 90° and the arm adducted at the side. Table 4.4 lists some common associations regarding elbow strength assessment.

Table 4.4 Strength assessment8

| Elbow strength assessment | Relative strength |

|---|---|

| Extension | 70% of flexion |

| Pronation | 85% of supination |

| Non-dominant arm | 90% of dominant arm |

Clinical assessment of specific elbow disorders

Epicondylosis

Lateral epicondylosis (tennis elbow)

Provocative manoeuvres include resisted wrist and long finger extension. Both of these will be more painful for the patient when the elbow is extended (Fig. 4.12). In addition, the examiner should check passive stretch of the ECRB by extending the elbow and passively flexing the patient’s wrist with the forearm in pronation. Each of these three manoeuvres should elicit pain over the ECRB origin and re-create the patient’s typical symptoms. Grip strength is a very useful objective test to evaluate response to treatment and recovery of function.

Medial epicondylosis (golfer’s elbow)

Patients with medial epicondylosis have pain on palpation of the common flexor–pronator origin on the anterior aspect of the medial epicondyle. The provocative manoeuvre for medial epicondylosis involves resisted wrist flexion and forearm pronation. This will cause more pain when the elbow is extended (Fig. 4.13), rather than flexed. Passive extension of the wrist with the elbow extended and supinated may also reproduce the patient’s typical pain. In patients with suspected medial epicondylosis, it is important to assess the ulnar nerve since associated ulnar neuropathy occurs in 50% of cases (see specific tests for cubital tunnel syndrome below). As with lateral epicondylosis, grip strength provides a useful objective measure of functional change over time.

Instability

Lateral collateral ligament pathology (varus and posterolateral rotatory instability)

Several clinical tests have been described to assess for lateral collateral ligament pathology (Table 4.5).

| Special tests for LCL pathology (varus and posterolateral rotatory instability) |

Posterolateral rotatory instability test (lateral pivot shift test)

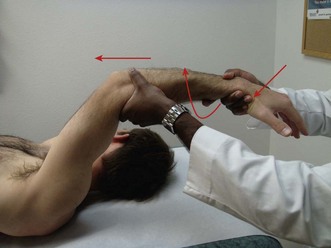

Described by O’Driscoll et al in 1991, the posterolateral rotatory instability test (lateral pivot shift test) is difficult to perform in the awake patient due to apprehension and guarding. The patient is positioned supine on the examination table with the affected shoulder placed in full forward elevation and in full external rotation. The examiner stands at the head of the table and grasps the patient’s wrist with one hand and braces the lateral aspect of the patient’s elbow with the other hand. Beginning with the elbow extended, the examiner fully supinates the patient’s forearm, applies an axial load with simultaneous valgus stress and brings the elbow from extension to flexion (Fig. 4.14). A positive test occurs when a palpable clunk is generated as the radial head reduces from the posteriorly subluxated or dislocated position to become reduced on the capitellum. Reduction usually occurs as the elbow approaches 40° of flexion.9 Taking the elbow from a flexed to an extended position causes the radial head to subluxate or dislocate posterior to the capitellum. A posterolateral skin dimple may be seen while the radial head is dislocated. O’Driscoll subsequently modified this test to one in which a positive test is denoted by apprehension of this manoeuvre. This is more easily elicited in the awake patient and is one of the most sensitive special tests for PLRI.10

Posterolateral drawer test

The patient lies supine with the shoulder extended and externally rotated. The elbow is flexed to 90° and the examiner grasps the proximal forearm while applying a posteriorly directed force (Fig. 4.15). Subluxation of the radial head and ulna denotes a positive test as these rotate away from the humerus and pivot on the MCL.10

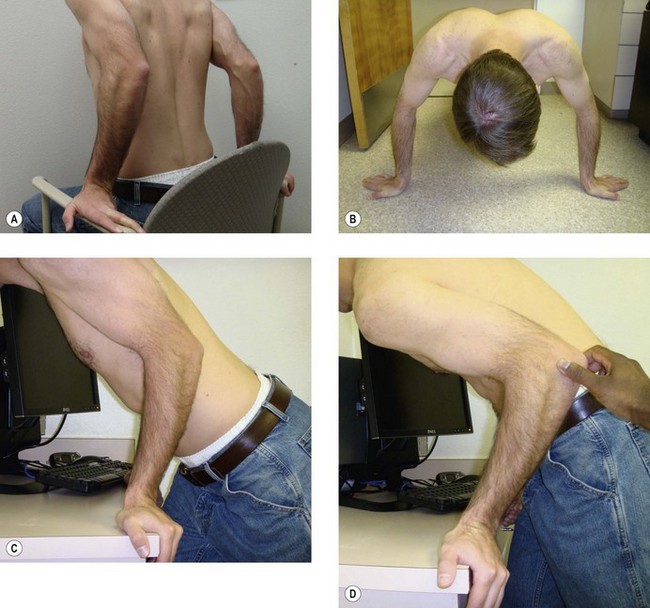

Chair sign, push-up sign, tabletop relocation test

Each of these manoeuvres is performed by the patient and, when positive, generates apprehension and pain. In the chair sign, the seated patient places their hands on the armrest in full supination and then pushes up from the chair using only the arms (Fig. 4.16A). As the affected elbow reaches 40° of flexion, apprehension is created. The same apprehension is generated when the patient performs a push-up with the affected forearm placed in full supination (Fig. 4.16B). Both of these signs were described by Regan and Lapner, and in their small series were noted to be more sensitive in the awake patient than the lateral pivot shift test.11

In the tabletop relocation test, the standing patient places the hand of the affected extremity in the fully supinated position on a table and pushes up from elbow flexion to extension (Fig. 4.16C). Again, apprehension is created at 40° of elbow flexion if PLRI is present. In this test, the patient then repeats the motion while the examiner places the thumb on the posterolateral aspect of the radial head to prevent subluxation (Fig. 4.16D). Relief of apprehension helps confirm a positive test and differentiates true PLRI from radiocapitellar articular pathology, which may cause a false positive result in any of these three tests.12

Hypersupination test

This is the test most commonly used by the authors to test for PLRI. It is easier to perform on the awake patient than the lateral pivot shift and posterolateral drawer tests. Unlike the lateral pivot shift test, which is a reduction manoeuvre, this test re-creates instability. The patient is positioned with the elbow at 90° of flexion. The examiner grasps the patient’s wrist with one hand and places the thumb of the other hand on the posterolateral aspect of the radiocapitellar joint. With hypersupination of the patient’s forearm the examiner palpates for radial head glide, subluxation or dislocation with respect to the capitellum. If instability is noted, pronation of the forearm will reduce the radial head. A dimple may be seen with subluxation of the radial head and, in addition, rotation of the ulna away from the lateral epicondyle may occur. The test should be repeated at about 45° of elbow flexion if it is equivocal or negative at 90° (Fig. 4.17). Whether in the clinic or in the operating room, performing this test under fluoroscopy will demonstrate the instability with posterolateral subluxation of the radial head on the capitellum and associated rotation of the ulna away from the trochlea (Fig. 4.18).

Medial collateral ligament pathology (valgus instability)

Injuries to the MCL may be traumatic or chronic in nature. Classically, high-velocity overhead-throwing athletes develop pain and instability with continued throwing after attritional injury to the MCL of the elbow. There are several clinical tests that help determine the presence and magnitude of instability (Table 4.6).

| Special tests for MCL pathology (valgus Instability) |

Valgus stress test

It may be difficult to detect valgus instability as the magnitude of joint laxity is often small, resulting in only a few millimetres of ulnohumeral opening. In addition, some overhead athletes may have increased unilateral physiological valgus laxity. Therefore, a comparison to the uninjured contralateral elbow, although important in every case, may not always be helpful. The patient is seated with the shoulder in maximal external rotation to lock the humerus in position, and the elbow is placed in 25–30° of flexion to unlock the olecranon from the olecranon fossa and to relax the anterior capsule. The examiner then braces the patient’s hand and wrist between their own arm and chest wall and applies a valgus stress to the elbow while palpating the medial ulnohumeral joint for increased opening with no definitive endpoint (Fig. 4.19). A soft endpoint may also indicate an attenuated or incompetent ligament. In Jobe’s original report using the valgus stress test in patients with confirmed MCL tears, 41 of 59 patients had a positive valgus stress test.13 The degree of instability is measured in millimetres of ulnohumeral opening and is considered positive when greater than 3 mm.

Moving valgus stress test

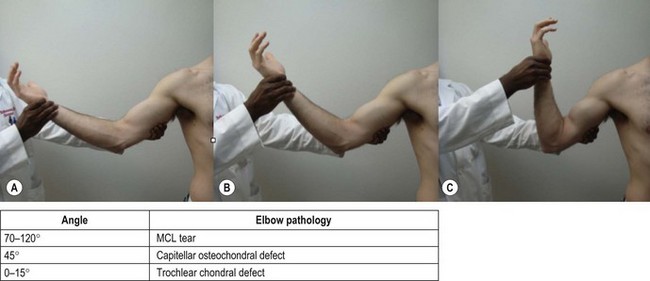

The patient is positioned such that the arm is abducted to 90° and is in maximum external rotation. The test is begun with the elbow in maximum flexion. The examiner grasps the patient’s wrist with one hand and places the other hand to pivot on the lateral aspect of the elbow. While applying a valgus stress to the elbow, the elbow is moved from full flexion to full extension (Fig. 4.20). Pain on the medial side of the elbow between 70° and 120° of elbow flexion denotes a positive test for MCL pathology. O’Driscoll described this test and reported it as both sensitive (100% in 17 patients) and specific (75% in 4 patients).14 Pain with the elbow at 45° is more indicative of a capitellar osteochondral defect, while pain at terminal extension may indicate a trochlear chondral defect.

Milking manoeuvre

This test derives from a common stretching manoeuvre done by baseball pitchers during warm-ups. The patient begins by placing the affected elbow on the antecubital fossa of the contralateral arm and then grasps the thumb of the affected extremity with the unaffected extremity. Pulling downward on the thumb with the elbow flexed greater than 90° creates a valgus moment, thus loading the MCL (Fig. 4.21). Pain elicited at the medial elbow with or without apprehension denotes a positive test for MCL injury.15 If the patient is not flexible enough to perform this unaided, the examiner may re-create the same effect by forward elevating and maximally externally rotating the arm of the patient and then applying a valgus stress to the flexed elbow. Again, a positive test elicits pain at the medial elbow.

Valgus extension overload test

Some overhead-throwing athletes with physiological MCL laxity or chronic MCL insufficiency will develop osteophytes at the posteromedial olecranon, with pain at terminal extension. To test for valgus extension overload syndrome, the elbow is gently forced into full extension with a valgus moment. Pain with this test, or tenderness to palpation over the posteromedial aspect of the olecranon, denotes a positive test and may indicate symptomatic abutment of osteophytes on the olecranon or in the olecranon fossa.16

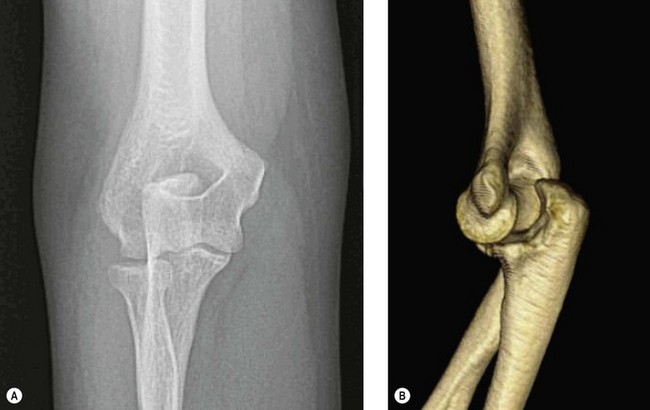

Posteromedial rotatory instability

This instability pattern typically occurs after a fall on the outstretched hand where the forearm is pronated, axially loaded and undergoes a varus stress. The anteromedial coronoid fails as the trochlea rotates and displaces anteriorly, while the lateral collateral ligament fails under tension at the lateral epicondyle. The posterior bundle of the MCL also tears due to ulnar rotation (Fig. 4.22).17 Tests for this type of instability include the varus stress test described above and the reverse pivot shift test.

Reverse pivot shift test

This reduction test is performed in an analogous fashion to the lateral pivot shift test. The patient is supine, with the affected shoulder in full forward elevation. With the elbow in extension, the forearm is pronated and a varus and axial load is applied to subluxate the elbow. As the elbow is gradually flexed the joint will reduce with an audible clunk or grinding sensation from the associated coronoid fracture (Fig. 4.23).

Tendon rupture

Distal biceps rupture

Examination of a patient with an acute distal biceps rupture will often display ecchymosis about the anteromedial aspect of the elbow. In the setting of a complete rupture, the biceps muscle is often proximally retracted and there is no rise and fall of the muscle with supination and pronation, respectively. Partial ruptures are more difficult to diagnose. Patients typically present with antecubital pain, aggravated by resisted elbow flexion and forearm supination. Tenderness over the bicipital tuberosity in the antecubital fossa is also commonly seen. Special tests to identify a complete distal biceps tendon rupture are listed in Table 4.7.

| Special tests for distal biceps tendon rupture |

Hook test

The hook test is very useful for diagnosing a complete distal biceps tendon rupture. With the patient’s elbow at 90° of flexion and the forearm in full supination, the examiner attempts to hook the distal biceps tendon with their index finger from lateral to medial. In the setting of an intact tendon, the examiner will be able to hook their finger behind the tendon (Fig. 4.24A). If there is a complete distal biceps tendon rupture, the brachialis tendon will be palpable but it will not be possible to place a finger behind it (Fig. 4.24B). O’Driscoll et al described this test in 2007 in a series of 45 patients using the uninjured arm as the normal control for the study. In this series, the authors reported a higher diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for the hook test (both 100%) than for MRI (92% and 85%, respectively).18 If the examiner brings the hooked finger from medial to lateral, an intact lacertus fibrosus may lead to a false negative test. Therefore it is important always to perform the hook test from lateral to medial.

Squeeze test

For this test, the patient is seated and has the elbow in 90° of flexion with the forearm resting on a table or on their lap. The examiner squeezes the biceps muscle belly and observes the forearm for passive supination. A positive test occurs when the distal biceps tendon is completely torn and no supination occurs (Fig. 4.25). With an intact tendon, the forearm should passively supinate.19

Distal triceps tendon rupture

In the acute setting, ecchymosis and swelling may be present about the posterior elbow. The examiner may be able to palpate a defect in the tendon just proximal to the olecranon tip in the presence of a complete rupture. In addition, the patient will be unable to extend the elbow against gravity. Viegas described a modification of the Thompson test to detect complete triceps tendon ruptures.20 The arm is supported with the elbow at 90° and the hand hanging free. In the presence of an intact tendon, the forearm will extend when the triceps muscle is squeezed. With a complete rupture, there will be no forearm extension. With a partial rupture, it may not be possible to palpate a defect. The modified Thompson test may show some forearm extension, and the patient may demonstrate some active elbow extension.

Arthritis

Osteoarthritis and post-traumatic arthritis

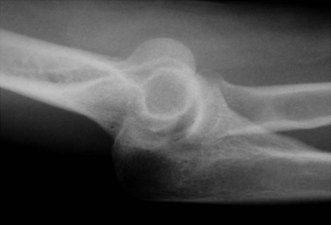

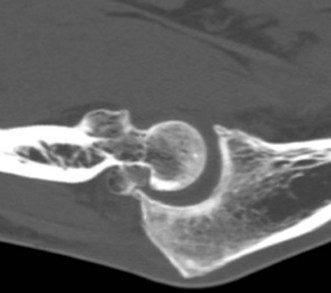

Patients with elbow arthritis often complain of pain, stiffness, swelling and mechanical symptoms such as locking or catching. Physical examination begins by means of inspection, with particular attention given to any swelling or deformity that may be present. Range of motion examination is important and specific attention should be directed toward impingement signs and crepitus. Impingement pain is pain experienced at the extremes of motion (flexion or extension) due to the impingement of hypertrophic osteophytes against one another. The build-up of osteophytes may not only cause pain but may also restrict range of motion (Fig. 4.26).

Elbow plicae

Elbow plicae typically occur at the radiocapitellar joint and represent a hypertrophied annular ligament.21 Patients describe pain and/or mechanical symptoms. Provocative tests to illicit snapping or pain from the plicae are listed in Table 4.8.

| Special tests for plicae about the elbow |

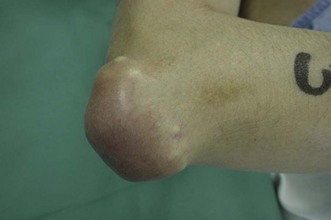

Bursitis

Olecranon bursitis is more readily examinable as it is typically obvious on initial inspection of the elbow (Fig. 4.28). Swelling and fluctuance are typical, and the patient may or may not be tender over the bursa. In septic olecranon bursitis, particular attention should be given to any erythema and its extent, as well as any breaches in skin integrity such as puncture wounds, lacerations or chronically draining sinuses.

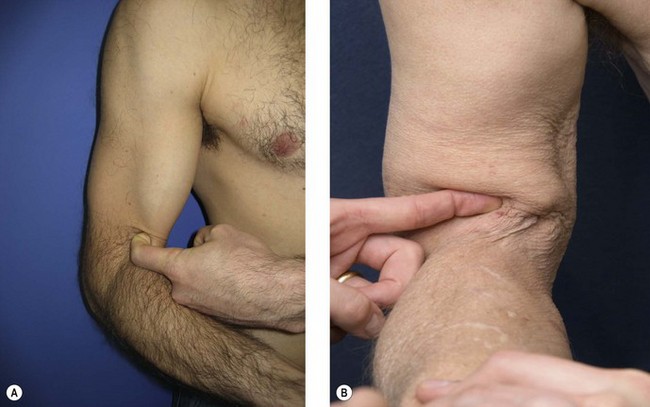

Subluxating ulnar nerve and snapping medial head of triceps

Ulnar nerve subluxation and a snapping medial head of triceps are medial elbow pathologies that are often overlooked. These conditions should be ruled out in any patient presenting with medial elbow pain. To assess for these conditions, the examiner supports the patient’s elbow on their open hand and places the thumb on the posteromedial aspect of the medial epicondyle. As the patient’s elbow is passively moved from extension into flexion, the ulnar nerve and medial head of the triceps are palpated to determine whether they displace anteriorly over the medial epicondyle. If both findings are present, it is important to remember that the ulnar nerve will likely subluxate first, followed by the medial head of the triceps (Fig. 4.29).22

Compression neuropathies

Cubital tunnel syndrome

Ulnar neuropathy is the most common nerve compression about the elbow. Physical examination includes inspection, motor and sensory examination, palpation and special tests. Inspection specific to ulnar neuropathy should assess the carrying angle of the elbow, any visible evidence of a subluxating ulnar nerve, any masses, atrophy of the hand intrinsics (especially atrophy of the first dorsal interosseous muscle) or hypothenar eminence, or any clawing of the small and ring fingers (Fig. 4.30).

Tinel’s test should be performed. A positive test reproduces paraesthesias into the small and ring finger by tapping the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel. Another provocative test involves maximally flexing the patient’s elbow with or without applying simultaneous pressure over the ulnar nerve just proximal to the cubital tunnel. Again, a positive test reproduces paraesthesias in the small and ring finger.23,24

Novak et al looked at the reliability of some of these more commonly performed provocative tests.25 Table 4.9 summarizes their findings.

| Sign | With cubital tunnel syndrome | Normal subjects |

|---|---|---|

| Tinel’s | 71% | 23% |

| Elbow flexion | 75% | 6% |

| Elbow flexion with pressure | 93% | 7% |

Other physical examination findings that may be present in severe ulnar neuropathy or with other ulnar nerve injury and dysfunction are listed in Table 4.10.

Table 4.10 High ulnar nerve palsy physical exam findings

Posterior interosseous nerve compression syndrome and radial tunnel syndrome

In contrast, radial tunnel syndrome presents with pain but no functional deficit.37 In many instances, it can be confused with the more commonly occurring lateral epicondylosis. To diagnose radial tunnel syndrome, the examiner should apply pressure over the arcade of Frohse, the most common site of compression as the posterior interosseous nerve enters the leading edge of the supinator muscle. This is located approximately 2 cm medial and 3 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle. One should compare the pain elicited to a similar test on the contralateral elbow, as this is often a tender area in the normal patient.

Provocative tests to identify PIN syndrome are typically nonspecific and may overlap with those for lateral epicondylosis. They include pain with resisted forearm supination, active forearm supination with simultaneous wrist flexion and resisted long finger extension with the elbow extended. Pain in the region of the arcade of Frohse with any of these manoeuvres constitutes a positive test.38,39

1 Morrey BF, Chao EY. Passive motion of the elbow joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(4):501-508.

2 Paraskevas G, Papadopoulos A, Papaziogas B, et al. Study of the carrying angle of the human elbow joint in full extension: a morphometric analysis. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004;26(1):19-23.

3 Zampagni ML, Casino D, Martelli S, et al. A protocol for clinical evaluation of the carrying angle of the elbow by anatomic landmarks. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(1):106-112.

4 Cain ELJr, Dugas JR, Wolf RS, et al. Elbow injuries in throwing athletes: a current concepts review. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(4):621-635.

5 Boone DC, Azen SP. Normal range of motion of joints in male subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61(5):756-759.

6 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Joint motion: method of measuring and recording. Chicago, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1965.

7 Morrey BF, Askew LJ, Chao EY. A biomechanical study of normal functional elbow motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(6):872-877.

8 Askew LJ, An KN, Morrey BF, et al. Functional evaluation of the elbow: normal motion requirements and strength determination. Orthop Trans. 1981;5:304.

9 O’Driscoll SW, Bell DF, Morrey BF. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(3):440-446.

10 O’Driscoll SW. Classification and evaluation of recurrent instability of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;370:34-43.

11 Regan W, Lapner PC. Prospective evaluation of two diagnostic apprehension signs for posterolateral instability of the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(3):344-346.

12 Arvind CH, Hargreaves DG. Table top relocation test: new clinical test for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(4):500-501.

13 Conway JE, Jobe FW, Glousman RE, et al. Medial instability of the elbow in throwing athletes: treatment by repair or reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(1):67-83.

14 O’Driscoll SW, Lawton RL, Smith AM. The ‘moving valgus stress test’ for medial collateral ligament tears of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(2):231-239.

15 Jobe FW, Kvine RS. Elbow instability in the athlete. Instr Course Lect. 1991;40:17-23.

16 Wilson FD, Andrews JR, Blackburn TA, et al. Valgus extension overload in the pitching elbow. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11(2):83-88.

17 O’Driscoll SW, Jupiter JB, Cohen MS, et al. Difficult elbow fractures: pearls and pitfalls. Instr Course Lect. 2003;52:113-134.

18 O’Driscoll SW, Goncalves LB, Dietz P. The hook test for distal biceps tendon avulsion. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1865-1869.

19 Ruland RT, Dunbar RP, Bowen JD. The biceps squeeze test for diagnosis of distal biceps tendon ruptures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;437:128-131.

20 Viegas SF. Avulsion of the triceps tendon. Orthop Rev. 1990;19(6):533-536.

21 Antuna SA, O’Driscoll SW. Snapping plicae associated with radiocapitellar chondromalacia. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(5):491-495.

22 Spinner RJ, Goldner RD. Snapping of the medial head of the triceps and recurrent dislocation of the ulnar nerve: anatomical and dynamic factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(2):239-247.

23 Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL. Surgery of the peripheral nerve. New York: Thieme; 1988. p. 79

24 Buehler MJ, Thayer DT. The elbow flexion test: a clinical test for the cubital tunnel syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;233:213-216.

25 Novak CB, Lee GW, Mackinnon SE, et al. Provocative testing for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg (Am). 1994;19(5):817-820.

26 Earle AS, Vlastou C. Crossed fingers and other tests of ulnar nerve motor function. J Hand Surg (Am). 1980;5(6):560-565.

27 Wartenberg R. A sign of ulnar nerve palsy. JAMA. 1939;112:1688.

28 Froment J. La paralysie de l’adducteru du pouce et le signe de le prehension. Rev Neurol (Paris). 28, 1914.

29 Mannerfelt L. Studies on the hand in ulnar nerve paralysis: a clinical-experimental investigation in normal and anomalous innervation. Acta Orthop Scand. 1966;87:1-176.

30 Jeanne M. La deformation du pouce dans la paralysie cubitale. Bull Mem Soc Chir. 1915;41:703.

31 Duchenne G. Reserches electro-physiologiqes et pathologiques sur les muscles de la main, et sur les extenseurs communs des doigts, extenseurs propes de l’index et du petit doigt. Arch Gen Med. 1851;25:361.

32 Masse L. Contribution a l’etude de l’achon des interosseus. J Med (Bordeaux). 1916;46:198.

33 Andre-Thomas T. Le tonus du poignet dans la paralysie du nerf cubital. Paris Med. 1917;25:473.

34 Mumenthaler M. Die Ulnarisparesen. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme; 1961.

35 Bunnell S. Surgery of the Hand, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 1956.

36 Bouvier S. Note sur une paralysie partielle des muscles de la main. Bull Acad Nat Med (Paris). 1851;18:125.

37 Lubahn JD, Cermak MB. Uncommon nerve compression syndromes of the upper extremity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(6):378-386.

38 Lister GD, Belsole RB, Kleinert HE. The radial tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg (Am). 1979;4(1):52-59.

39 Sponseller PD, Engber WD. Double-entrapment radial tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg (Am). 1983;8(4):420-423.