The present chapter will consider not only the mechanical aspects of the problem, but also the impact on the autonomic nervous system of factors such as menstruation, infection, meteorological changes, hormonal disturbances, or psychological stress. Because the term ‘back pain’ is altogether inadequate for a proper clinical understanding, it will be imperative to focus close attention on each individual section of the spinal column.

7.2. Pain in the thoracic spine and thorax

The thoracic spine is the least mobile section of the spinal column. Because of this stability it is only relatively rarely the site of the primary lesion in dysfunctions. On the other hand, pain in the thoracic region is often referred pain from the viscera, and it is here that vertebrovisceral inter-relationships are most clearly apparent. A special warning against diagnostic error is particularly apposite in this region. One important condition that manifests itself primarily in the thoracic spine is juvenile osteochondrosis, the commonest cause of kyphosis in adolescents. Stiffness of the kyphosed thoracic spine has to be compensated for by lumbar hyperlordosis, and it is there that pain is most commonly felt.

Patients complain mostly of pain between or below the shoulder blades. Here, again, pain in the dorsal region may be the result of excessive strain due to external factors or to muscle imbalance and excessive static loading. One particularly common culprit is a kyphotic sitting position associated with working at the computer. The typical muscle imbalance is shortening of the pectoralis major and weakness of the interscapular muscles and of the lower fixators of the shoulder blade. Major stiffness is detected especially at the point where the kyphosis peaks. On the other hand, hypermobility can also be linked with pain, generally in a flat back in the upper thoracic region.

Movement restrictions may be present not only in the apophyseal joints between the individual vertebrae but also at the joints between vertebrae and ribs, and they produce very similar symptoms. Deep breathing can be painful in both scenarios. Of course, this is particularly the case with rib lesions, where it is useful to distinguish between pain on inhalation and pain on exhalation. It is essential for the differential diagnosis to exclude pleural disease.

The techniques for diagnosis and therapy have been discussed in the appropriate sections in

4 and

6, with regard to both movement restrictions and TrPs. The deep stabilization system with TrPs in the diaphragm and pelvic floor also plays an important role here. Patients with restricted trunk rotation suffer not only from low-back pain but also from pain between or beneath the shoulder blades (attachment points of the iliocostal muscle).

Therapy and self-mobilization (see

Figure 6.74) simultaneously serve to strengthen the interscapular component of the erector spinae. Where painful tender points are present at the sternocostal joints, specific relaxation of the bundles of the pectoralis major with insertion there has proved effective (see

Figure 6.109). While highly effective, self-mobilization (see

Figure 6.38) is indicated only if lordosis in the thoracolumbar region does not occur in the process.

Less frequently than in the lumbar and cervical spine (where acute low-back pain and acute wry neck are common conditions), acute episodes of pain may occur in the thoracic spine, due especially to rib dysfunction. Such episodes can be even more dramatic than acute low-back pain or neck pain, because patients are unable not only to move but also even to breathe without pain. Manipulation and mobilization are complicated by the fact that mere contact at the rib is excessively painful; on the other hand, local anesthesia at the transversocostal joint is easy to perform because the structure is superficial. However, a similar acute pain on respiration may also be produced in the very early stage of pneumonia (before the typical rise in temperature).

7.2.1. Slipping rib

Symptoms

Here attention will be drawn to a clinical condition that is by no means rare but is only seldom recognized. Slipping rib presents as intense pain localized in the lower thorax and upper abdomen, sometimes associated with pain on respiration and coughing (or sneezing). Large, forceful movements of the upper extremity on the side of the lesion may also be painful. Generally, suspicion falls on a wide variety of diseases of the thoracic and upper abdominal organs, and these patients usually undergo a great many visceral examinations (which all prove negative).

Therapy

Therapy consists of

mobilization using the fingers hooked beneath the inferior costal arch to exert repetitive springing pressure ventrally and laterally. This mobilization is always painful but generally brings instantaneous relief. Only in exceptional cases is

local anesthesia necessary at the inner margin of the tenth rib, while surgical removal of the painful rib may be considered as a last resort. Treatment of the spinal column or of the costovertebral joints is ineffective in this condition and the true pathogenesis is unknown.

C M; female; born 1929.

Medical history

First seen by us on 4 June 2002 complaining of burning pains in the thorax, usually occurring at rest and apparently without any provoking factors. Onset of pain just one month previously. The patient had undergone surgery in 1992 to remove her left breast, after which she experienced transient swelling of the feet; no symptoms at all prior to surgery.

Clinical findings and therapy

Restricted movement at C3/C4 to the left side, TrPs in the diaphragm on the left side, the thoracic fascia on the left side showed reduced mobility relative to the underlying structures, and the fifth sternocostal joint was painfully tender. The fascia was treated and the attachment point of the pectoralis at the fifth costotransversal joint was released. The restriction at C3/C4 was also treated, after which the TrP in the diaphragm could no longer be palpated.

At follow-up examination on 25 June 2002 the patient reported no major improvement. She also still complained of ‘spasm-like back pain.’ On this occasion a slipping rib (left side) was diagnosed and treated. Following further examination on 4 July 2002 the patient’s condition was considerably improved, and she reported feeling only slight tension in the axilla. The serratus anterior was found to be shortened; this was relaxed and stretched. Relaxation of the serratus anterior was then assigned as her home exercise.

Case summary

The slipping rib was found to be crucially important for the symptoms experienced by this patient. The far more typical findings made at the initial examination proved to have little relevance.

7.5. Entrapment syndromes

Entrapment syndromes have become fashionable especially in circumstances where the intention is to ignore the potential role of dysfunctions. It is then possible to explain pain in terms of trapped nerve structures. This view fails to recognize that pain is registered not in the nerve itself but in its receptors. In principle, neurology teaches us that peripheral nerves process not only pain but also other modalities. Therefore if nerve compression causes pain at all, then alongside pain other modalities (including motor activity) must also be impaired. Consequently, if only pain is present without hypesthesia or weakness, we should never simply assume nerve compression or an entrapment syndrome.

The entrapment syndromes of the upper extremity not infrequently occur in combination.

7.5.1. Carpal tunnel syndrome

This condition is attributed to compression of the median nerve in the narrow tunnel formed by the carpal bones and crossed by the transverse carpal ligament. Compression first affects the blood vessels supplying the nerve, and this explains the important role of ischemia.

Symptoms

The patient complains chiefly of numbness and tingling in the hand and fingers, and later also of pain. In the initial stages, these symptoms are felt only on waking up in the morning but later they are sufficiently severe to waken the patient at night. In the more advanced stage, pins and needles and pain are felt even during the day, particularly on raising the arms. Pain may then also radiate up the arm as far as the shoulder. Relief is obtained when the arms hang down loose, while shaking the hands improves the blood supply. Heavy physical work exacerbates the symptoms.

Clinical signs

In the initial stages, we have to provoke the symptoms for the purpose of examination; the simplest method is to instruct the supine patient to raise the arms vertically and then wait to establish whether paresthesia occurs. In the more advanced stages, pressure or percussion on the median nerve above the wrist may elicit a sharp tingling pain (Tinel’s sign). There is also constant hypesthesia in the territory of the hand supplied by the median nerve and weakness with atrophy of the abductor pollicis brevis; this muscle must always be tested. Characteristic thenar wasting is encountered only in the advanced stages of the disease. On the basis of our own experience we would stress that even in the early stages of carpal tunnel syndrome increased resistance is found when testing joint play between the carpal bones.

Therapy

In the early stages,

mobilization,

carpal bone distraction and

stretching of the transverse carpal ligament are indicated (see

6.98,

6.99,

6.100 and

6.101) and self-applied traction is prescribed as a home exercise (see

Figure 6.82). It has been found to be particularly helpful for patients to wear an orthosis or elasticated support at night to fix the wrist in mild dorsiflexion, the position in which intra-articular pressure in the carpal tunnel is least pronounced.

If increased resistance is not detected when joint play is tested, local anesthesia or cortisone preparations may also be tried. In the stage characterized by incipient weakness and atrophy and by typical electromyography changes, surgery to release the transverse carpal ligament is usually indicated.

Pathogenesis

The carpal tunnel is a channel that is formed by a large number of small bones that move in relation to one another. This channel must be able to accommodate its contents comfortably in response to every type of hand movement. It is easy to understand, therefore, that a disturbance of joint play will result in conflict between the walls of the channel and its contents, and that restoration of joint play constitutes a form of treatment that reflects the pathogenesis.

K O; female; born 1936.

Medical history

The patient first came to us on 24 June 2003 complaining of tingling in her right hand that kept her awake at night. To get rid of it she had to get up and shake her arm. The symptoms started on or about 10 June 2003 after she had been painting a fence.

Clinical findings

Examination disclosed increased resistance on testing for joint play of the carpal bones and tingling was promptly elicited in the arm elevation test with the patient supine.

Therapy

The individual carpal bones were mobilized and distraction manipulation was performed at the wrist. The patient was prescribed an orthosis to wear at night.

Case summary

Typical carpal tunnel syndrome in the functionally reversible stage. This was diagnosed most elegantly using the arm elevation test with the patient supine; tingling was elicited after a brief latency period.

7.5.2. Thoracic outlet syndrome

This syndrome is attributed to compression of the brachial plexus mainly in the gap between the anterior and middle scalenes and the muscle attachments at the first rib, and in the region of the superior thoracic outlet. Principally, it causes paresthesia (numbness, pins and needles, pain) in the upper extremities, this being most intense on the ulnar aspect of the fingers.

This syndrome is predominantly the result of dysfunctions involving the highly complex structures that constitute the superior thoracic outlet. The prerequisite for effective therapy is to identify any disturbances in these individual structures and their relevance in each case. In detail, these comprise increased tension (TrPs) of the scalenes, TrPs in the pectoralis minor (

Hong & Simons 1993), increased tension of the upper fixators of the shoulder girdle, and TrPs in the diaphragm. Closely related to these muscle disorders, there may be movement restriction at the craniocervical junction, the cervicothoracic junction, and the upper ribs, in particular the first rib. The true cause of this increased tension (TrPs) is clavicular breathing (i.e. lifting the thorax during inhalation), which is associated with insufficiency of the deep stabilizer system.

It is no wonder, in view of this complexity and the lack of understanding concerning dysfunctions, that surgical decompression procedures are performed on the scalenes, the first rib, or a cervical rib, instead of pursuing the true cause, the treatment of which is highly rewarding.

Symptoms

The symptoms consist principally of paresthesia involving the upper extremity (including the hands), more apparent on the ulnar aspect, and typically becoming worse when carrying heavy loads. Because of the plethora of individual dysfunctions, the clinical picture (especially the pattern of pain) is anything but uniform; for example, headache may also be present due to movement restriction at the craniocervical junction. It is worth emphasizing that, by contrast with the carpal tunnel syndrome, severe weakness or atrophy rarely occur.

Clinical signs

The following tests are useful for provoking the symptoms:

• Adson’s maneuver: the pulse at the radial artery is weakened (or disappears) on bending the patient’s head back and turning it to the same side.

• Hyperabduction test: the patient’s arm, bent at the elbow, is taken into maximal abduction and the radial artery pulse is palpated.

• Pulling the arm downward, as when carrying a load, and feeling for the radial artery pulse.

More important, however, is diagnosis of the individual dysfunctions in the region of the superior thoracic outlet. Only in exceptional cases are there signs of neurological deficit. Cervical myelopathy is generally present where there is major weakness with atrophy and, of course, paresthesia.

Therapy

Therapy depends on the analysis of the individual clinical findings forming the links in the chain. Given the unmistakable role of the scalenes, it is evident that clavicular breathing is the crucial factor in the pathogenesis, coupled with involvement of the deep stabilizer system.

B I; female; born 1960.

Medical history

First seen on 18 October 2000 complaining of pain in the cervical region with stiffness, headache, shoulder pain, and tingling in the fingers. Her symptoms started in the cervical region, and she had experienced tingling in her hands for the past two or three years, especially when working at the computer for long periods. Apart from an operation to correct hallux valgus, her other details were unexceptional.

Clinical findings and therapy

Examination disclosed thoracic dextroscoliosis, increased tension in the scalenes on both sides, and movement restriction of the first rib on both sides and of the cervicothoracic junction. The patient’s breathing was normal. Her first rib and cervicothoracic junction were treated and her scalenes were relaxed; self-mobilization of the first rib was assigned for home exercise.

At the follow-up examination on 1 November 2000 the patient felt better, less stiff, and reported only occasional tingling in her hands. TrPs were now detected in the subscapularis and pectoralis major on the left side, and her thoracic fascia showed poor mobility relative to underlying structures. When the fascia were treated the TrPs disappeared; self-treatment of the thoracic fascia was recommended as a home exercise (see

Figure 6.62 b).

The patient was seen again on 16 May 2001. She had been symptom-free up to the start of that month, but now her neck was painful again and she was experiencing tingling in her hands. She also complained of shortness of breath. TrPs were found in the diaphragm and again there was increased tension in the scalenes with restricted movement of the first rib on both sides. Her left fibular head was also restricted. Her diaphragm and scalenes were relaxed, the first ribs and cervicothoracic junction were treated, and her fibula was mobilized. As a home exercise we prescribed relaxation of the diaphragm and self-treatment for the first rib.

On 5 June 2001 she had only transient tingling in her fingertips. Her pelvic floor was painful on the right side. Her pelvic floor was relaxed and her fingertips were treated using skin stretching.

The patient was again symptom-free and appeared for a further examination on 9 May 2002. Since April 2002 she had been complaining of shortness of breath, with feelings of tightness in the left half of her thorax. Since the beginning of May she had also been experiencing pain in her neck and upper extremities. Once again there were TrPs in the diaphragm and TrPs on the left side in the pectoralis major, psoas major, quadratus lumborum, pelvic floor, hip adductors, and biceps femoris, and movement restriction at the fibular head. After PIR of the diaphragm, all TrPs were eliminated, including the restriction at the fibula; only the first ribs with the cervicothoracic junction were treated. On 11 June 2002 the patient had only tingling in her fingertips, and this was treated with skin stretching; her scalenes were also relaxed.

The patient was once more symptom free until 4 August 2004 when she was seen again because tingling had reappeared in her upper extremities and fingertips and she was experiencing knee pain. Examination now revealed only skin changes at the fingertips and tingling on the soles of her feet; these were treated by exteroceptive stimulation. The thoracic outlet syndrome itself was no longer present.

Case summary

Typical thoracic outlet syndrome with increased tension in the scalenes (although without characteristic clavicular breathing), and with the repeated finding of TrPs in the diaphragm and pelvic floor (coccygeus). The ‘glossy skin’ changes at the fingertips (erasure of skin creases and slight reddening) are not unusual in this context. Skin stretchability at the fingertips is invariably limited, and skin stretching eliminates tingling. The combination of increased tension in the scalenes and TrPs in the diaphragm often produces feelings of tightness, interpreted by this patient as shortness of breath.

7.5.3. Ulnar nerve weakness

Ulnar nerve weakness will be mentioned here only in passing. The cause is generally to be found in the ulnar nerve canal and only very rarely in Guyon’s canal in the wrist region. This condition is not an object for manipulative therapy, but it does need to be distinguished from the two entrapment syndromes described above. In terms of carpal tunnel syndrome it is necessary to differentiate between median nerve and ulnar nerve involvement. In terms of differentiation from the thoracic outlet syndrome, it is important to identify patterns of weakness and atrophy that are characteristic of the ulnar nerve, as well as a true hypesthesia, since these hardly ever occur in thoracic outlet syndrome.

7.5.4. Nocturnal meralgia paresthetica

This condition is the commonest entrapment syndrome affecting the lower extremity.

Therapy

Therapy consists of relaxation of the iliopsoas and tensor fasciae latae muscles.

V V; male; born 1950.

Medical history

The patient had complained of numbness and pain on the lateral surface of the left thigh since February 1988. Otherwise he had never been ill.

Clinical findings

Examination on 13 April 1988 revealed TrPs in the psoas major and iliacus on the left side. Trunk rotation was restricted to the right (40° to the right and 60° to the left) and extension was restricted at L5/S1. Hypesthesia in the territory characteristic for the lateral cutaneous femoral nerve was detected on the lateral aspect of his left thigh.

Therapy

Treatment consisted of mobilization of trunk rotation to the left and mobilization of L5/S1. For exercising at home the patient was recommended to self-treat using gravity-induced PIR of the iliopsoas and tensor fasciae latae.

When seen again on 5 December 1988 the patient complained of pain between the shoulder blades. Asked about the pain in his thigh, he reported that this had cleared up within a few days.

7.7. Active scars

In a publication dating from 1947, Huneke described how symptoms of pain in the locomotor system, often at remote locations, subsided immediately following local anesthesia of scars, a finding that he termed the ‘instant relief phenomenon’. He attributed this effect to the use of novocaine. While at the time his observations attracted widespread attention and ushered in the era of neural therapy, that is administration of local anesthetics into pathogenic foci (Dosch 1964,

Gross 1979), general interest in its use for the treatment of scars slipped back into oblivion.

Despite this, the efficacy of treating scars continued to be investigated and over the years it was found that it was not the local anesthetic but rather the act of needling that was responsible for the effect (

Lewit 1979). However, the crucial development here was that the clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and therapy of soft tissue came to be recognized. Today, scars have become a model for the study of soft-tissue pathology. This is because a scar may involve all layers, from the epidermis, subcutaneous tissue, muscles, and fascia, right through to the abdominal cavity, for example, and each layer has to be diagnosed and treated separately.

All these layers share a common feature: if they do not behave normally, then their ability to stretch and move relative to each other is impaired. As with all other mobile structures, it is also necessary here to differentiate between a normal (physiological) barrier and a pathological one. Where a pathological barrier is diagnosed, we speak of ‘active scars’. And it is only when the surface of the skin is stroked that we may also diagnose increased skin drag, which enables us to recognize active scars very quickly.

The importance of active scars in pathogenic terms is also easy to understand: when our body moves, this movement is not limited to our muscles, joints, and bones, that is the locomotor system proper, but all other tissues have to contribute harmoniously to this movement, that is they have to stretch and shift relative to each other. If this associated movement is disturbed (and this is a largely neglected field of research), then the function of the locomotor system will also be impaired by reflex mechanisms. And this also applies to the visceral organs.

7.7.1. Diagnosis

At first sight the diagnosis of an active scar appears to be extremely straightforward: in each layer we look for a

pathological barrier, that is we test for skin stretch, subcutaneous folding and stretching of the fold, the typical resistance pattern of TrPs, the degree to which fascia and areas of resistance can be shifted, and pathological barriers in the abdominal cavity. However, the following

difficulties should be highlighted, on the basis of extensive clinical experience: in the case of surgical scars, the skin incision is often selected so as not to produce a cosmetic blemish. However, the actual surgical procedure involving the deeper-lying structures may take place some distance away from the incision, and this fact needs to be realized if pathological barriers are to be detected there. The diagnosis of resistance in the abdominal cavity demands special skill. Surgery today makes widespread use of laparoscopic procedures, and for this reason nothing will be palpated in the superficial layers. We therefore have to rely on our palpatory skill if we are to identify the location and direction of resistance in the abdominal cavity. And it is no less important to be able to recognize the release phenomenon reliably; for if there is no release phenomenon, then we are dealing not with a scar but with a pathological process in the abdominal cavity. The requisite diagnostic steps then have to be initiated. Clinically, it is important that palpation for resistance should not be limited to areas above the pubic symphysis. Resistance is commonly found below the symphysis in toward the pelvis, especially after gynecological operations, and complicated deliveries are a frequent cause. As abdominal scars are stretched by backward bending they restrict extension of the lumbar spine, and the patient interprets this as low-back

pain. In the absence of segmental restriction in the lumbar spine, backward bending is then restored by treatment of scars in the abdominal region.However, diagnosis alone is not enough; it is also important to determine relevance. An active scar need not necessarily be a factor in the symptoms for which the patient is being treated. In order to determine relevance, a complete examination should be followed initially by treatment of the scar so that we can determine whether or not the dysfunctions and their chain reaction pattern can be influenced by our intervention there. This is important because if the effect is positive, then we continue to target the scar with our treatment. Conversely, if a relevant active scar is not treated, then all other therapy will remain unsuccessful.

7.7.2. Therapy

In every case therapy consists of taking release through to the very end. In the case of areas of resistance in the abdominal cavity it is often necessary to change direction, depending on where further resistances can be palpated. The patient will often indicate where the referred pain is felt in the locomotor system (usually in the back). It is important to understand that a single treatment will not usually suffice and that it is generally helpful also to stroke the skin surface and to prepare the deeper layers for treatment by using hot packs. The number and frequency of treatments will be determined by the clinical course.

The pathogenic effect of resistance in the abdominal cavity depends not on the organ or even on its position, or whether this or that structure in the abdominal cavity is palpated, as practitioners of visceral osteopathy insist. It is determined solely by the pathological barriers in the abdominal cavity that interfere with the harmonious cooperation of the viscera as the body moves.

B W; female; born 1967.

Medical history

First seen on 3 October 2000 complaining of pain in her arms and shoulders. She had given birth three years previously; the baby weighed 4kg and the patient lost a great deal of blood, had a high fever, and received antibiotics. Her shoulder pain started soon after the baby was born.

Clinical findings and therapy

Examination of the patient revealed a chain of TrPs extending down to her left foot. The patient’s history evoked a suspicion of an active scar in her lower abdomen, and in fact resistance was palpated in her left hypogastric region. Once the release phenomenon was obtained, the patient’s symptoms (including TrPs) cleared up.

At follow-up examination one month later the patient’s condition had largely improved, treatment in the lower abdomen was repeated and at the same time her cervicothoracic junction was treated by traction manipulation. After this the patient was symptom-free.

Case summary

This case is instructive for the following reasons: the patient’s symptoms started shortly after she had given birth; palpation of her hypogastric region confirmed painful resistance; and a release phenomenon was obtained, simultaneously with the ‘instant relief phenomenon’ described by

Huneke (1947).

7.9. Vertebrovisceral inter-relationships

7.9.1. General principles

The possibility that reflex inter-relationships between different structures may exist side by side with referred pain in the same body segment has already been discussed in

Section 2.11. The practical clinical aspects of this phenomenon will now be considered.

In very broad terms, the following five

possibilities should be envisaged:

1. The spinal column (motion segment) is causing symptoms that are mistaken for visceral disease.

2. Visceral disease is causing symptoms that are interpreted as a lesion in some part of the locomotor system.

3. Visceral disease is producing changes in the locomotor system, such as TrPs, movement restrictions, etc.

4. Visceral disease that has caused changes in the locomotor system has subsided; however, the resultant dysfunctions have persisted and are simulating visceral symptoms.

5. A disturbance in the motion segment is triggering visceral disease or (more likely) is activating already latent visceral symptoms (hypothetical).

The first two points highlight the necessity for precise differential diagnosis and the problems associated with this. The spinal column with its motion segments can in fact produce symptoms that may mimic symptoms arising in the viscera and that are frequently interpreted as such by both patients and practitioners. This explains why patients who have been successfully treated by lay manipulators believe they have been ‘cured’ of their visceral disease.

No less important is the fact that these differential diagnoses are not always sufficiently recognized; consequently, when no pathological changes are found in the visceral organs, the term ‘functional’ is used to describe these disturbances. And given the prevailing ignorance concerning dysfunctions, the word ‘functional’ tends to be used as a euphemism for ‘of psychogenic origin’ or even for ‘malingering’. As already stated in

Section 1.1, any practitioner who finds no pathological changes to corroborate a diagnosis should first look for a disturbance in the corresponding segment of the locomotor system before labeling a disorder as psychogenic. The pejorative use of the word ‘functional’ in general and especially in connection with the locomotor system reflects a lack of awareness that tends to underestimate the significance of locomotor system dysfunctions. It is this underestimation, combined with ignorance, that gives unqualified lay manipulators the opportunity to claim ‘miracle’ cures.

The other side of the coin (point 2) is the warning that pain perceived in the locomotor system may be a deceptive sign masking serious underlying visceral disease. This suspicion is strengthened if the symptoms of spinal segmental disturbance tend to relapse repeatedly without obvious cause. While the error in point 1 is more common, that in point 2 is all the more fraught with danger.

Point 3 is of major theoretical significance and demonstrates that visceral disease is actually one of the possible causes of dysfunction in the motion segment (see

Section 1.1). Clinical experience teaches that certain visceral diseases are associated with characteristic patterns in the locomotor system. These patterns are of considerable diagnostic importance and are described below. They are so specific that their recurrence is in all probability predictive of a recurrence of the visceral disease. It is therefore literally ‘in our hands’ to make the diagnosis and influence the prognosis.

Point 4 follows on from point 3. If the visceral disease has been cured and we manage to treat the reflex dysfunctions caused by it, we obtain most satisfactory results and can thus confirm the success of visceral treatment. Here patients and practitioners alike tend to draw the following incorrect conclusion: because of persistent symptoms due to secondary dysfunctions in the motion segment, the patient still feels affected by the visceral disease. If after treatment of the dysfunction the patient is symptom-free, all the credit for the success of therapy is then given to the practitioner who treated the dysfunction, even though the underlying visceral condition had already been cured. However, if the dysfunction recurs in the same motion segment, this is generally an early sign of a recurrence of the visceral disease.

Point 5 is the pipe-dream cherished by many (lay) practitioners in the past; even today, however, it remains conjectural. Nevertheless, it would seem

justifiable to assume that lesions in a motion segment of the spinal column may impair function in the corresponding internal organs. This is borne out by the vasomotor response in the whole segment to which pain is referred. In such cases we can see the disorder clearing up as soon as we treat the motion segment. Reactions of this kind have been noted particularly in connection with the cervicocranial syndrome, especially at the craniocervical junction, including disturbances of equilibrium. Similar phenomena have been observed in connection with certain cardiac arrhythmias. According to Schwarz (1996), a motion segment dysfunction may activate latent disease in an internal organ. Multiple pathogenic factors may also need to be considered in terms of their cumulative impact. As well as those that affect the locomotor system, other factors may be important in terms of their influence on the organism as a whole, for example infections, metabolic disturbances, menstruation, diet, etc. None of these individual factors on its own would be sufficient to provoke disease, but it is legitimate to refer to them as risk factors.

7.9.2. Tonsillitis

Systematic questioning when taking the case history in patients with vertebrogenic disturbances reveals a strikingly high incidence of tonsillitis. In a randomly selected sample of 100 cases from our files, 56 patients had a history of chronic relapsing tonsillitis and/or tonsillectomy. This finding was made particularly often in patients with movement restriction of the occiput against the atlas. It therefore seemed justifiable to investigate this problem further.

In a study sample of 76 predominantly adolescent patients with chronic tonsillitis, movement restriction at the craniocervical junction was detected in 70 cases, in the great majority of them between the occiput and atlas. Following tonsillectomy, movement restrictions were still present in the vast majority of these cases. However, where movement restrictions were previously not present or had been treated, they developed only in exceptional cases after tonsillectomy. They could therefore not be interpreted as a consequence of surgery.

In 40 non-operated patients in long-term follow-up who underwent just one manipulative procedure, 26 remained without tonsillitis recurrence and 15 without movement restriction recurrence (

Lewit & Abrahamovič 1976). Thirty-seven of these patients were followed up again three years later. Eighteen patients remained without tonsillitis recurrence, but in 7 cases movement restriction did recur and had to be treated. Two patients had a few recurrences of tonsillitis without movement restriction, 3 suffered repeatedly from tonsillitis, and 9 underwent tonsillectomy. In total, 13 patients remained without any recurrence of movement restriction. Interestingly, the tonsillitis patients had hardly any HAZs in the cervical region, but there was increased muscle tension (

défense musculaire) laterally at the floor of the mouth below the tonsillar bed.

It can be concluded from this study that chronic tonsillitis goes hand in hand with movement restrictions at the craniocervical junction, mainly in segment C0/C1, and that these have a tendency to become chronic. This means that there is a danger of permanently disturbed function in one of the key regions of the locomotor system. In addition, our experience suggests that movement restriction in this region is associated with an increased susceptibility to recurrent tonsillitis.

7.9.3. The lungs and pleura

Recognition of the close interplay between respiration and the locomotor system has also improved our understanding of the relationship between the lungs and the function of the thorax. Pronounced clavicular breathing or paradoxical breathing may be the underlying cause of dyspnea in the absence of any disturbance of the organs of respiration. Of course, pain experienced in the context of pleurisy or pneumonia needs to be differentiated from pain due to rib movement restriction or a slipping rib.

Palpation of rib mobility is useful here. In pleural disease the impairment of mobility involves the greater part of one side of the thorax whereas movement restrictions affect one or just a few motion segments.

The respiratory disease in which involvement of the thorax has been studied most is

obstructive respiratory disease (

Bergsmann 1974,

Köberle 1975,

Sachse & Sacshe 1975,

Steglich 1971). The following factors play a key role here: rigidity of the chest wall further increases resistance during respiration, and the inspiratory position of the thorax in asthma patients is worsened by clavicular breathing, which is typical for that disease. Movement restrictions of the ribs are also associated with pulmonary rigidity,

as detected by Köberle (1975) principally in segments T7–T10. In a group of 23 patients,

Sachse & Sachse (1975) found a taut pectoralis major in 15 cases and a weakened lower trapezius in 15 cases. Increased tension in the scalenes is the most frequent change associated with clavicular breathing. TrPs in the diaphragm are also common.

Therapy comprises mobilization of movement restrictions in the thoracic spine and ribs, and remedial exercise for asthma patients who adopt a clavicular breathing pattern, so that respiratory resistance (which is increased in this disease) can be kept as low as possible.

As a result of thoracic rigidity, extremely pronounced clavicular breathing in combination with abdominal breathing, both with and without shortness of breath, is often encountered in ankylosing spondylitis. This is important because despite the presence of ankylosis, specific remedial exercises can achieve a correct thoracic breathing pattern thanks to the elasticity of the ribs.

7.9.4. The heart

Of all the vertebrovisceral inter-relationships, that between the heart and the spinal column has received most attention. This is due not only to the importance of the problem, but also to the fact that in the largest group of patients, that is in those with angina, the role of pain is comparable to that in thoracic dysfunctions. Pain of cardiac origin is also felt in the thorax, while pain referred from the heart is localized mainly to the shoulder and left arm.

Patients with angina show a characteristic pattern of disturbance that includes movement restrictions involving the thoracic spine, especially segments T3–T5 and most commonly T4/T5, the third to fifth ribs on the left side, the cervicothoracic junction, and often the craniocervical junction. Most commonly, TrPs are located paravertebrally at the level of T4, in the pectoralis major, subscapularis, serratus anterior, and upper part of the trapezius on the left side. TrPs in the scalenes go hand in hand with painful sternocostal joints in the vicinity of T3–T5 on the left side where the attachment points of the pectoralis minor are also located. Clavicular breathing is also often encountered in this setting, with the patient experiencing sensations of tightness not dissimilar to those felt in angina.

It is obviously imperative to distinguish as clearly as possible between angina with its characteristic pattern of disturbances and the

pseudocardiac syndrome emanating primarily from the locomotor system.

Rychlíková (1975) has shown that the more complete the described pattern of (reflex) changes in the locomotor system, the more likely it is to be secondary to primary heart disease. A number of important clinical criteria can aid the distinction between true angina and pseudoangina. Pain in true angina is dependent on physical effort, such as climbing stairs, and responds within seconds to administration of nitroglycerine. Retrosternal pain also tends to be indicative of a cardiac origin. On the other hand, pain provoked by certain positions of the body or by specific movement(s) is more characteristic of pseudoangina. Attacks are shorter in true angina than in the pseudoangina syndrome. The course of the disease is also different: if locomotor system dysfunctions recur or are aggravated despite specific treatment, this should be taken to indicate that the true cause is primary heart disease. The role of the locomotor system in pain of cardiac origin is borne out by the fact that

Rychlíková (1975) did not find any signs of locomotor system dysfunction in a group of patients who suffered a myocardial infarction without pain.

Regardless of whether the locomotor system dysfunction pattern is primary or secondary, its treatment is always justified, as is rehabilitation for locomotor system dysfunction. If increased resistance is detected when shifting fascia around the thorax, the gentlest approach is to begin by releasing the fascia before using neuromuscular treatment techniques that address movement restrictions and TrPs simultaneously. This is followed by rehabilitation with training to correct breathing and posture. In view of the difficulties of diagnosis, cardiological monitoring is always indispensable. In cases where cardiological treatment is successful and locomotor system dysfunctions recur during the course of rehabilitation, it should be emphasized that these are often the first sign of a recurrence of heart disease, even before any evidence appears on the electrocardiograph (ECG).

The prime significance of the treatment of locomotor system dysfunction in heart disease lies in the relief of pain, which greatly enhances the rehabilitation of these patients, as illustrated by the following case study.

K H; female; born 1937.

Medical history

The patient reported pain between the shoulder blades and radiating into her neck and thorax, mainly on the left side. The pain had an acute onset on the morning of 5 February 1980. The patient reported retrosternal ‘burning,’ and an ECG was taken, revealing normal findings. The patient first became aware of pain in her neck and thorax in 1976. In her youth she had repeatedly suffered from angina. She had also received psychiatric treatment for depression. The patient played basketball as an adolescent.

Clinical findings and therapy

Examination on 9 December 1980 revealed a bilateral movement restriction at C0/C1, and limited retroflexion at T4/T5 and T6/T7. TrPs were present in the pectoralis major and there was a pain point at the sternocostal joint at T4 on the left side. The patient also presented with pronounced clavicular breathing but without any increase in scalene muscle tension. The movement restrictions at C0/C1, T4/T5, and T4/T7 were treated, as well as the painful attachment point of the pectoralis major at the fourth sternocostal joint. The patient experienced relief immediately after treatment and a start was made on correcting her faulty breathing pattern.

On 6 January 1981 the patient developed acute cervical myalgia with a typical movement restriction to the right at C2/C3 and C5/C6. Isometric traction and mobilization of C5/C6 was followed by traction manipulation of C5/C6 with the patient seated, and a residual TrP in the upper part of the trapezius was treated by PIR. On 13 January 1981 the patient was symptom-free. This was evidently a case of a vertebrocardiac syndrome.

7.9.5. The stomach and duodenum

As in heart disease, painful conditions in these organs may well produce reflex changes in the locomotor system. We had the opportunity to study the characteristic pattern in a group of young

ulcer patients aged between 15 and 22 years (

Rychlíková & Lewit 1976). The characteristic pattern of disturbance was noted primarily in segment T5/T6. Compared with a control group of similar age, there was an increased incidence of movement restrictions at the craniocervical junction. However, the most striking finding was pelvic distortion (87% as compared with 44.4% in the controls). There was also increased muscle tension in the thoracic erector spinae in segments T5–T9 on both sides, with a maximum at T6, and a HAZ in the same region on both sides – also significantly more common than in the control group. It is interesting that these changes were almost symmetrical, with a very slight preponderance on the right side. However, there was no difference between the cases of gastric and of duodenal ulcer.

In this group, the intensity of reflex changes correlated with the intensity of pain; where there was no pain, as in some cases after surgery, there were also no locomotor system dysfunctions. It must be added that this was the pattern found in young patients; in older patients suffering from ulcers the incidence of pelvic distortion is very much lower.

V S; male; born 1922; X-ray technician.

Medical history

Since 1960 the patient had suffered from low-back pain that radiated into his thighs. He had been treated for a gastric ulcer since 1948.

Clinical findings and disease course

7.9.6. The liver and gall bladder

Because pain is a prominent feature in disorders of the liver and gall bladder, reflex changes must be anticipated here too. According to

Rychlíková (1974), the motion segments most frequently affected by dysfunction are T6–T8. There is also frequently pain that is referred to the right shoulder, as borne out by a HAZ in the C4 dermatome and TrPs in the upper part of the trapezius on the right. Non-inflammatory gall bladder dysfunction can sometimes be halted successfully using reflex techniques.

Professor L O; male; born 1906; theater manager.

Medical history

The patient was referred to us for treatment because of chronic low-back pain radiating into both legs. Despite many treatments, his symptoms had been constant since 1956. He also complained of pain between the shoulder blades that troubled him particularly when he moved his head.

Clinical findings and therapy

When he was examined on 18 January 1961 the patient omitted to mention his gall bladder condition. Pelvic distortion was detected, together with faulty movement patterns that necessitated remedial exercise therapy. On 11 July 1961 the patient complained of gall bladder pain. His low-back pain worsened. On 26 October 1961 he suffered an episode of biliary colic that made remedial exercise impossible. Extensive HAZs were found in the thoracic region and there was a painful spinous process at T9, which was treated by rotation manipulation. The pain disappeared almost at once. The patient returned regularly for follow-up until 1965 and there were no further recurrences of biliary colic.

7.9.7. The kidneys

Reflex changes are most clearly apparent in patients with

renal colic. They always occur on the painful side in segments T10–T12 in the lower back and pain radiates into the groin. A thorough analysis of reflex changes in the locomotor system in kidney disease has been made by

Metz (1986). In 208 cases of chronic kidney disease (

glomerulonephritis, pyelonephritis) he found the following pattern: movement restriction at the thoracolumbar junction (T11–L1), and increased tension at the lowest ribs and in the psoas major, quadratus lumborum, and the thoracolumbar erector spinae. Metz emphasized that pain only became manifest in these patients with ‘genuine’ renal disease when the above locomotor system findings were apparent.

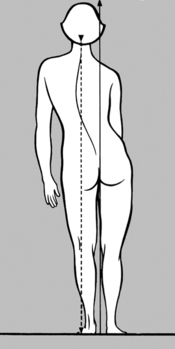

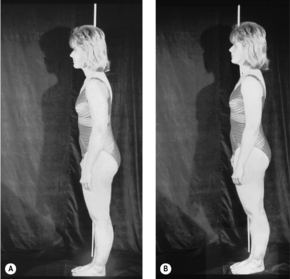

Pelvic distortion and a markedly increased incidence of faulty statics in the lumbar spine and pelvis were present (according to Metz) especially in nephroptosis (downward displacement of the kidney), where the symptoms were also determined decisively by locomotor system dysfunctions. Symptoms and locomotor system disturbance patterns were identical in a group of 40 patients with nephroptosis and another 40 patients after nephropexy: they primarily involved the thoracolumbar junction with unilateral hardening of the psoas major. The patients were mainly asthenic, hypermobile women with faulty statics, recurrent movement restrictions at L5/S1, and ligament pain. (Nowadays we would seek to identify insufficiency of the deep stabilization system.) In these cases, however, locomotor system dysfunction proved to be the decisive cause of the renal symptoms.

7.9.8. Importance of the psoas major and rectus abdominis

TrPs in the psoas major may also be the cause of pain in the ‘post-cholecystectomy syndrome.’ Like other painful structures in the abdominal cavity, TrPs in the psoas major may also give rise to tension and rigidity (défense musculaire) in the rectus abdominis. Because of the location and size of the psoas major, TrPs in this muscle can simulate symptoms associated with most of the abdominal viscera: duodenum, gall bladder, kidneys, pancreas, and vermiform appendix. Not only is the pain intense, but there may also be autonomic reactions such as loss of appetite and a feeling of indigestion, etc. Therapy involving PIR and RI is simple and effective.

Increased tension in the abdominal muscles, especially the

rectus abdominis, is often a sign of painful visceral disease. However, it is also encountered in locomotor system dysfunction, particularly in patients with a forward-drawn posture on standing, where it is caused by a chain reaction pattern extending from the feet via the fibula and associated with TrPs in the biceps femoris. As a result the anatomical fixation of the pelvis is disturbed from below, leading to TrPs in the rectus abdominis with painful attachment points at the pubic symphysis, xiphoid process, and neighboring ribs, with forward-drawn posture, restricted retroflexion while standing, and (referred) low-back pain (see

Figure 6.121). Needless to say, TrPs in the abdominal muscles are also capable of simulating visceral pain.

7.9.9. Gynecological disorders and low-back pain

Gynecological disorders have always been traditionally associated with low-back pain. From our modern-day perspective the role of gynecological disorders as a leading cause of low-back pain in women has been overestimated. It was the gynecologist

Martius (1953) who placed critical emphasis on the importance of the locomotor system.

Novotný & Dvorák (1984) conducted a study in 600 women attending a gynecology clinic at the University of Prague. They subdivided these patients as follows: the first group comprised 113 women with dysmenorrhea and normal gynecological findings who had low-back pain with typical onset at the menarche. This condition rarely deteriorates and very often improves after childbirth. A second large group developed symptoms during pregnancy and after delivery, that is dysfunctions occurred at a period when there is increased strain on and vulnerability of the spine and pelvis. A third group consisted of 59 patients with gynecological conditions giving rise to low-back pain. These were apparently viscerogenic disorders. The fourth and largest group of patients were women suffering from minor dysfunctions of the spine and pelvis, in whom gynecological examination was carried out as a routine diagnostic procedure, but with negative findings.

In a group of 150 pregnant women, 48 had a history of dysmenorrhea (

Lewit et al 1970). Of these 48 patients, 38 had lumbosacral movement restriction or pelvic distortion. Findings in the lumbosacral spine and pelvis were ‘normal’ in only 10 women. ‘Normal findings’ meant that pain was generally felt only in the hypogastric region but not in the lumbar region. Moreover,

low-back labor pains during an otherwise normal delivery were closely correlated with dysfunctions of the spinal column and pelvis.

In another group of 70 women with menstrual pain and normal gynecological findings, treatment of the spine, mainly by manipulation, brought considerable improvement in 43 cases, improvement in 13 cases, and no improvement in 14 cases.

In summary, it appears that low-back pain may have its origin in the female pelvic organs and may become manifest during childbirth and menstruation as well as following gynecological disease or surgery. In a very large number of patients, low-back pain is of locomotor system origin and is mistakenly attributed to primary gynecological disturbances. One reason for this may be a TrP in the iliacus which is palpated as a site of tender resistance in the hypogastric region. Menstrual pain with otherwise normal gynecological findings, especially when localized in the low back, is usually of vertebrogenic origin and is often the first clinical manifestation of locomotor system dysfunction

Labor pains felt in the low back in an otherwise normal delivery should also be interpreted as being of vertebrogenic origin. Current knowledge also points to the importance of the pelvic floor. Screening for a TrP there should also be conducted as routine (see

Figure 4.12) and, if found, its treatment is a major preventive factor.

Research conducted by

Mojžísová (1988) and

Volejníková (1992) suggests that manual therapy may offer some prospect of success in women with sterility of cryptogenic origin (i.e. with negative organic findings).

In women with locomotor system dysfunction, history taking should include questions to elicit information about dysmenorrhea, especially in adolescence, and low-back labor pains during childbirth.

B B; female; born 1933.

Medical history

The patient had suffered from headaches since the age of 12, and subsequently from metrorrhagia and pain on menstruation. She was first referred to us by her gynecologist on 16 October 1958.

Clinical findings and therapy

Examination revealed pelvic distortion with deviation to the left, and her left PSIS was painful as was retroflexion in the lumbosacral region. Segments C1/C2 and L5/S1 were treated.

On 15 January 1959 the patient reported that menstruation was much improved but her headaches were unchanged. Manipulation of L5/S1 and of the cervicothoracic junction was repeated.

The patient subsequently reported that menstruation now lasted for one week instead of two weeks as in the past, and her headaches were more bearable. She remained under our treatment but her headaches never disappeared completely. Low-back pain was now present only from time to time.

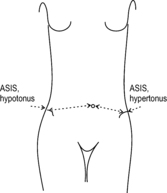

On 20 February 1962 menstruation had again increased to eight or nine days. Pelvic distortion to the left had returned and temperature measurement revealed a difference of 0.5° at the PSIS. Treatment of the lumbosacral junction was repeated.

The patient was last seen by us on 9 July 1967 because her menstrual pain had worsened. On this occasion we detected pelvic distortion to the right.

Case summary

The case of this patient repeatedly illustrates the dependence of menstrual symptoms on lumbosacral segment dysfunction.

7.10. Post-traumatic states

The important role of trauma in the causation of vertebrogenic disorders was pointed out in

Section 2.4.7 and it was emphasized in

Section 4.1 that a record of

trauma in the patient’s history is a

characteristic feature of vertebrogenic disorders. Right from childhood people are exposed to the risk of injury, and when spinal dysfunction is detected in children, trauma is often one of the key causes. These dysfunctions may remain latent and unnoticed due to compensatory adjustments (by other motion segments, for example), and these in turn may lead on to secondary changes.

In this way, the ground is prepared that allows the effects of subsequent trauma to be even more devastating. Trauma impacting an already compromised spinal column readily produces further decompensation, and even apparently trivial trauma may set this in motion. The words ‘apparently trivial trauma’ deserve emphasis here because the forces acting on the spinal column are so great that even an uncoordinated movement may expose it to a sudden load amounting to several hundred kilograms.

Once the acute consequences of trauma have subsided, it is often noted that there is a latency period after which the post-traumatic syndrome develops gradually – a pattern that is typical in cranial trauma, for example. It is often forgotten that the spinal column also suffers following most injuries to the extremities, the trunk and, in particular, the head. In the initial phase, however, the local injury takes center stage, and because the spinal effects are still in the latency period referred to above, they are commonly neglected.

7.10.1. Cranial trauma

To illustrate this point, let us take

concussion as an example. It stands to reason that any force acting on the head must also affect the cervical spine. Similarly, from the size and weight of the human skull compared with the

cervical spine, it will be obvious which of these two structures represents the site of lessened resistance, in relative terms. It is also therefore no coincidence that the majority of injuries to the cervical spine, including vertebral fractures, are concomitant effects of craniocerebral trauma. This fact is also borne out by autopsy

findings: without exception, in all 20 cases of death after head injury, Leichsenring (1964) also found serious damage to the cervical spine.

We can only concur with

Junghanns (1952) who wrote that symptoms usually attributed to concussion were in reality caused by trauma to the cervical spine. And this opinion is also shared by Gutmann and others. In fact, a striking similarity exists between the post-concussion syndrome and the cervicocranial syndrome. In both conditions, patients experience headache that is frequently paroxysmal and is associated with dizziness or vertigo. This was first described by Barré & Liéou (1926) as ‘

posterior cervical sympathetic syndrome’ and later by

Bärtschi-Rochaix (1949) as ‘

cervical migraine’ occurring in the wake of cranial trauma.

The close relationship between concussion (closed head injury) and whiplash injury is also evident from a study conducted by

Torres & Shapiro (1961) in which they compared the clinical and

electroencephalogram (EEG)

findings after concussion or whiplash injury. The neurological findings were virtually identical, with the difference that pain was more common in the neck and arms after whiplash injury. EEG abnormalities were present in 44% of patients after concussion and in 46% of patients after whiplash injury. In both cases temporal lobe foci were seen predominantly.

With ever-increasing numbers of vehicles on the roads, the incidence of whiplash injury is rising all the time. Whiplash injury often causes disproportionately severe symptoms and poses a problem in terms of therapy. Such incidents usually involve an

unexpected rear-end impact that causes the trunk of the individual(s) leaning back against the automobile seat to suddenly jerk forward at high speed; in this process the head and neck engage in a whiplash movement relative to the trunk. This can be particularly harmful if the head is also rotated relative to the trunk. Immediately after the accident it is common for the whiplash injury victim to feel that little of note has occurred, with any symptoms being minimal. It is not until hours or a few days later that the often considerable symptoms of a severe post-traumatic cervicocranial syndrome develop, and these commonly take a chronic course. In very recent whiplash injury, gentle examination often reveals hypermobility, whereas movement restrictions develop later due to muscle TrPs.

T M; female; born 1949.

Medical history

The patient was first seen by us on 25 May 1959 complaining of headache. In November 1958 she had received a blow in the neck from a school bag and had experienced intense local pain to begin with. She then vomited before lunchtime. Ever since that first day she had had headaches every day and had to stay at home for three weeks. At the time of her initial presentation she was suffering from headaches several times a week, localized to her occiput, frontal region, and sometimes involving her entire head.

Clinical findings and therapy

The clinical findings were unexceptional, although X-rays revealed dextrorotation of the axis. A repositioning effect was achieved by manipulation and at the follow-up examination on 22 October 1959 the patient stated that she had been symptom-free up until the middle of October when the pain had returned, prompting the repeat of manipulation (after five months).

Case summary

In this young girl’s case the blow to her cervical spine simulated a post-concussion syndrome with headache and vomiting.

As this case illustrates, forceful rear-end impact is not the only mechanism capable of causing whiplash injury. For example, it may also be produced by a fall on to the shoulder and we even know of one case where the condition was brought about by the impact of a wave against the head while the patient was in the sea. Although the underlying mechanism bears some similarity to distortion, the clinical course is far more severe. In computed tomography scans obtained in such patients, Dvorák (1989) detected tears in the alar ligament with hypermobility of the craniocervical junction, a finding that explains the often unfavorable response to HVLA thrust techniques.

One complication of whiplash trauma has been described by Berger (personal communication) under the designation ‘

stiff or frozen neck syndrome’. He has reported the following characteristic pattern based on an analysis of 20 cases: movement is restricted, slow and jerky on

cervicomotography (which involves registration of head movements in three planes simultaneously: fast movement; slow movement, eyes and head following a pendulum; passive movement). Passive movement is less restricted than active, and slow movement has a greater range than fast movement. Rotation with the patient supine (fixation at T1) is less restricted than rotation in the sitting position. There is marked hypertonus in muscles and soft tissues and there are extensive HAZs. Patients report intense pain radiating into the head and arms, often accompanied by dizziness and blurred vision. In this stage, patients cannot tolerate any type of physical therapy, whether mobilization, manipulation, or massage. They require immobilization, a supportive cervical collar, and sometimes cryotherapy.By 1965 we had followed up more than 65 post-concussion patients who had lost consciousness after an accident. Abnormal neurological findings (signs of disturbed equilibrium) were present in one case. By contrast, clinical findings in the cervical spine were normal in only six cases. The results of manipulation and reflex therapy were excellent in 37 cases, good in 8 cases, and unsatisfactory in 10 cases.

In a further group of 95 cranial trauma patients without concussion, seen during the period from 1964 to 1970, movement restrictions involving the cervical spine were absent in only 4 cases. Interestingly, the predominant finding was movement restriction at C1/C2. A painful anteflexion test, indicative of ligament pain, was present in 10 patients who were treated without success.

From the perspective of

prevention, the acute stage following trauma is most important of all. In this respect, post-concussion patients offer a model for acute spinal trauma because they are routinely admitted to hospital and therefore are not lost to medical examination. With a view to preventing later complications, a series of 32 patients in the acute post-trauma stage was referred to us for examination and treatment. All the patients were fully conscious, with no suspicion of intracranial hemorrhage, and with negative X-ray findings in the skull and cervical spine. A chronic disease course evolved in only one patient, who also developed arterial hypertension. Treatment was further unsuccessful in one patient with dizziness and a calcaneal fracture. Twenty-four patients (75%) became symptom-free immediately after treatment.

K E; female; born 1941.

Medical history

The patient had slipped and fallen over on 5 April 1958. Although she did not lose consciousness after the fall, she vomited and complained of headache.

Clinical findings and therapy

Neurological findings were normal. The transverse process of the atlas was tender to the touch and its movement was slightly restricted. The pain ceased instantaneously following manipulation on the left side.

At follow-up examination on 12 August 1958 the patient reported that she had experienced no further symptoms at all since manipulation.

K J; male; born 1910; bricklayer.

Medical history

The patient fell from a height of 2 meters on 6 August 1958 and was unconscious for a short time. When first seen by us on 7 August 1958 he complained of pain in the temples.

Clinical findings and therapy

His nasopalpebral and labial reflexes were exaggerated, and head rotation to the right was restricted. After treatment of C1/C2, head rotation was normal.

At follow-up examination on 23 April 1959 the patient notified us that he had been entirely symptom-free since manipulation.

V B; male; born 1910.

Medical history

While riding his motorbike, the patient collided with an automobile and was unconscious briefly, later complaining of headache with dizziness.

Clinical findings and therapy

At examination, Hautant’s test showed deviation to the right with first-degree nystagmus to the left. However, manipulation was not successful.

Bartel, 1980a and Bartel, 1980b has published almost identical results: in 50 cases examined immediately after head injury he detected movement restriction in all patients but 2, the lesion being most frequently located at C1/C2. In 40 cases, a single treatment was sufficient, usually involving neuromuscular techniques. Treatment had to be repeated in 6 cases, in 2 of these without success. (As a historical footnote to the three case studies presented above, it should be pointed out that neuromuscular techniques were still unknown in 1958.)

These experiences suggest a preventive role for manipulative therapy in acute head injury while movement restrictions are still in the early stage. Lack of awareness and understanding concerning manual diagnosis and therapy means not only that this opportunity is frequently missed but also that the patient complaining of pain quite literally has insult added to injury, being told that there are no organic findings and hence the pain must be ‘all in the mind.’

7.10.2. Trauma to the extremities

What is true for head injury is equally valid for other parts of the locomotor system: a patient who falls on a hand may also suffer from indirect injury to the cervical spine, while one who falls on a foot may also sustain injury to the pelvis and lumbar spine. A fall on to the shoulder may have the same effect as whiplash injury.

A number of typical lesions are encountered in the extremities after injury. A fall on to the hand, whether the radius is fractured or not, generates a force on the radius that pushes it upward at the elbow, causing dysfunction at the elbow joint. Clinically, this is often manifest as pain at the styloid process; and this may not start until after the plaster cast has been removed following a Colles’ fracture. Examination then regularly reveals impaired radial abduction at the wrist with movement restriction between the radius and ulna; however, the cause is located at the elbow where there are signs of a lateral epicondylopathy. Any treatment administered at the site of the pain is futile, but pain is immediately relieved by treatment for movement restriction at the elbow.

A fall on to the shoulder is likely to affect not only the cervical spine but also the structure that bore the direct brunt of the impact, namely the acromioclavicular joint and/or a first rib.

After foot injury, with or without fracture, we usually find movement restrictions in the tarsometatarsal and intertarsal joints, as well as in the ankle joint. After knee injury there is often movement restriction at the fibular head.

Functional coxalgia is not uncommonly the sequel to a sprain of or fall on to the hip. Appropriate mobilization or manipulation is the proper procedure immediately after injury, and the effect is often seen promptly. However, this depends on diagnostic precision in excluding fracture and hematoma. Early treatment will avoid later complications and prevent the condition from becoming chronic.

As described in Section

7.1.8, major lesions such as outflare and inflare dysfunction result mainly from trauma following a fall on to the buttocks (coccyx).

7.11. The clinical picture of dysfunctions in individual motion segments

7.11.1. The temporomandibular joint (TMJ)

The main symptom is headache on the side of the affected joint, with pain radiating strongly into the ear and face. When taking the patient’s history, questions should always be asked about missing teeth, badly fitting false teeth, or trauma. However, pain may also be caused by increased tension in the masticatory muscles, and psychological tension (teeth grinding, bruxism) may also be a factor. The masticatory muscles are in a chain with the muscles at the craniocervical junction and consequently the clinical picture may be difficult to distinguish from dysfunction at the craniocervical junction. Dizziness or vertigo or possibly tinnitus may also be present. Dysphagia and dysphonia may be noted where there is increased tension at the floor of the mouth, also involving the digastricus.

7.11.2. Atlanto-occipital segment

Patients commonly complain of headache felt at the occiput, mainly on one side. History taking often reveals evidence of recurrent tonsillitis or otitis media. Pain typically occurs in the morning and may waken the patient during the night.

TrPs are located primarily in the short extensors of the craniocervical junction and in the upper part of the sternocleidomastoid. Other pain points are found at the posterior arch of the atlas, at the transverse processes of the atlas, at the nuchal line, and at the posterior margin of the foramen magnum. Mobility testing reveals restriction of anteflexion and retroflexion most commonly, followed by restriction of side-bending to the left, and then of side-bending to the right. Joint play is reflected in dorsal shifting of the occipital condyles relative to the atlas. As with all motion segments in the cervical spine, there is frequently an important TrP in the diaphragm. The mobility of the scalp is restricted relative to the underlying tissues.

7.11.3. Atlantoaxial segment

Dysfunction in this segment is most commonly the result of trauma, but otherwise it is encountered less frequently. Although headache predominates, neck pain is usually also present.

There is a typical pain point at the lateral surface of the spinous process of the axis, more commonly on the right side. There are characteristic TrPs in the sternocleidomastoid and levator scapulae. Head rotation is restricted, usually to the right, whereas side-bending (‘nodding’) is more often restricted to the left. This is the only cervical segment in which rotation restriction is not necessarily in the same direction as restriction of side-bending. In this segment, rotation takes place precisely around a vertical axis.

7.11.4. Segment C2/C3

This is the segment where acute wry neck occurs. However, this does not mean that it is the only segment in acute wry neck where movement is restricted.

The most prominent TrPs are found in the sternocleidomastoid, levator scapulae, and the upper part of the trapezius. Pain may therefore be felt not only in the head but also in the shoulder. A pain point is routinely found at the lateral edge of the spinous process of the axis (usually on the right side), and rotation and side-bending are usually restricted to the right.

7.11.5. Segments C3/C4–C5/C6

Although headache may be present, pain referred to the arms is the characteristic finding here, in particular epicondylar pain at the elbow, more frequently on the lateral aspect. This may occur in combination with pain at the styloid process and with tenovaginitis that is common on the forearm.

Most TrPs are found in the deep layers of the paravertebral muscles, in the upper part of the trapezius, in the middle part of the sternocleidomastoid, and in the muscles with increased tension in epicondylar pain – the supinator, the finger and hand extensors, and the biceps and triceps brachii. Movement restriction at C3/C4 is sometimes also accompanied by symptoms of restriction at the

craniocervical junction. There may be ‘binding’ of the cervical fascia.

7.11.6. The cervicothoracic junction (C6/C7–T2/T3)

Even here headache is no exception, but cervicobrachial and shoulder pain in particular is typical, in association with paresthesia. All the joints of the shoulder may thus be involved, as well as the first ribs.

Muscle tension is increased (with TrPs) primarily in the upper and middle parts of the trapezius, and in the sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, diaphragm, subscapularis, and infraspinatus as well as in the corresponding fascia. Together with the movement restrictions at the cervicothoracic junction, the scalenes and the pectoralis minor are responsible for the thoracic outlet syndrome, which is frequently in a chain with the carpal tunnel syndrome.

7.11.7. Thoracic segments T3/T4–T9/T10

Because pseudovisceral pain is particularly common in these segments, differential diagnosis is of prime importance. Symptoms on the left side may simulate pain from the heart, lung, stomach, and pancreas; on the right side they may simulate pain from the gall bladder, liver, duodenum, and lung. If thoracic pain is not of visceral origin, it is usually secondary to dysfunction either of the cervical or of the lumbar spine (assuming that the patient is not suffering from a severe form of juvenile osteochondrosis). The exception to this rule is pain in the region where thoracic kyphosis peaks and the erector spinae is weakest, approximately at the level of T5. In rib dysfunctions there may also be pain at the sternocostal joints, which provide the main attachment points for the pectoralis major and minor. If the rib lesion is acute, breathing in and out is painful. Painfulness in the vicinity of the inferior costal arches is a characteristic sign of a slipping rib.

The most important TrPs are in the pectoralis major and minor subscapularis, serratus anterior, erector spinae, the diaphragm and pelvic floor, and only rarely in the latissimus dorsi. The mobility of the deep fascia is disturbed on the back (in a cranial direction) and especially around the thorax.

7.11.8. Restricted trunk rotation (segments T10/T11–L1/L2)

Pain is characteristically felt in the low back or between the shoulder blades. If the condition is acute, the patient will often volunteer the information that it has been provoked by straightening up suddenly from anteflexion with rotation. Because limited trunk rotation is not due to restricted joint movement but to TrPs in the thoracolumbar erector spinae, psoas major, and quadratus lumborum, the pain is felt principally at the attachment points for these muscles – at the iliac crest (low back) and at the lower ribs (below the shoulder blades), but hardly ever at the thoracolumbar junction. Kyphotic posture is the consequence of psoas spasm, which may also provoke pseudovisceral symptoms. If TrPs are simultaneously present in the abdominal muscles, then the pubic symphysis and xiphoid process may be tender. There is a viscerovertebral inter-relationship between these motion segments and the kidneys. Trunk rotation here is generally restricted in the direction opposite to the side where the muscle TrPs are located.

7.11.9. Segment L2/L3

It is rare for this segment to suffer from dysfunction; when it does, it causes low-back pain. TrPs are found in the gluteus medius, below the iliac crest.

7.11.10. Segment L3/L4

Like the other more caudal lumbar segments, dysfunction here is characterized by pain that is referred to the lower extremities. It is largely identical to pain originating in the hip joint, and is felt in the hip and the groin, radiating ventrally down the thigh to the knee and sometimes beyond as far as the tibia.

Muscle spasm with TrPs in the rectus femoris is characteristic, and therefore the femoral nerve stretch test is positive; the straight-leg raising test is usually negative. Further TrPs are found in the hip adductors, and for this reason Patrick’s sign is mildly positive.

7.11.11. Segment L4/L5

Pain in this segment is felt in dermatome L5 that travels down the lateral aspect of the leg, from the thigh to the lateral malleolus.

The characteristic TrP is in the piriformis, and therefore pain is felt mainly in the hip. There is usually also increased tension in the hamstring muscle group, especially the biceps femoris, and the straight-leg raising test is therefore positive. There may be pain and movement restriction at the fibular head. Increased tension in the rectus femoris and hence also in the ischiocrural ligament and piriformis muscle often results in secondary movement restriction at the sacroiliac joint.

7.11.12. Segment L5/S1

The pattern of pain here is consistent with dermatome S1, and radiates down the back of the leg as far as the heel and lateral malleolus.

There is increased tension in the hamstring muscle group and the straight-leg raising test is positive. As in dermatome L5, there is therefore often movement restriction of the fibula, with secondary sacroiliac restriction. A TrP in the iliacus is very characteristic, with pseudovisceral symptoms in the lower abdomen. In hypermobile patients there is often a pain point at the spinous process of L5.

7.11.13. The sacroiliac joint

Because the pattern of pain distribution here too is consistent with dermatome S1, it is virtually indistinguishable from that experienced in lumbosacral movement restriction. Owing to the wide variations in anatomical topography in this region, the pain point (indicated by many patients as lying above and medial to the PSIS) cannot be differentiated from the neighboring lumbosacral joint.