Chapter 26 Classification of Knee Dislocations

INTRODUCTION

The concept of a dislocated knee has changed markedly over the past few decades. In 1971, Meyers and Harvey10 predicted that most orthopaedists would not see more than one knee dislocation in their entire career. However, evidence indicates that knee dislocations are being seen with increasing frequency for a variety of reasons. Increasing trauma, changes in automotive design, and recognition of spontaneously reduced knee dislocations have all added to the increased incidence. The increasing number of knee dislocations has created the need for a classification system that will help guide the management of these complex injuries. Classification systems should be simple and reproducible; they should give information to the clinician that will be helpful in making treatment decisions and aid in the communication of like injuries as well as in developing prognoses for injuries. This chapter reviews the shortcomings of the older classification systems of knee dislocations and presents the anatomic classification system that is simple, accurate, reproducible, and useful.18–20,28

DEFINITION OF KNEE DISLOCATION

Classically, a knee dislocation was defined as greater than 100% displacement of the tibiofemoral articulation. This displacement had to be present on either physical examination or radiographic imaging. Since the 1990s, several authors have recognized the existence of “reduced” knee dislocations. These are knees that present to the treating physician reduced but have multiple injured ligaments (usually including both cruciates) and gross instability on stress testing. Some of these injuries represent a spontaneous reduction of a knee dislocation, and others are dislocated knees that are reduced in the field before transport to a medical facility. The incidence of this type of reduced knee dislocation may be as high as 50% of all knee injuries classified as a dislocation.3,28,32 A study from our institution showed that the incidence of vascular injury in the reduced dislocations was equal to that of knees that presented dislocated (Fig. 26-1).32 In general, more recent studies have shown that the risk of arterial injury is approximately 7% to 12% with a diagnosis of a dislocated knee.26 Clinicians must be alert to the presence of reduced dislocations in order not to miss a limb-threatening arterial injury, as shown in Figure 26-1. A multiligament-injured knee with gross instability must be treated the same as a knee that presents dislocated.

Critical Points ASSESSMENT OF KNEE DISLOCATIONS

Although most knee dislocations involve tears of both cruciate ligaments (posterior cruciate ligament [PCL] and anterior cruciate ligament [ACL]), case reports of cruciate-intact knee dislocations do exist. A PCL-intact knee dislocation was first described in 1975.11 Several authors2,23 have reported on patients with a radiographically documented knee dislocation that, upon reduction or operative exploration, demonstrated a functioning PCL or ACL. Although some of these patients were noted to have suffered partial PCL tears, the presence of a functioning PCL provides increased stability and changes the management of these PCL-intact dislocations. In most PCL-intact knee dislocations, the tibia is perched anterior on the distal femur (Fig. 26-2). In addition to an ACL tear, there is often complete rupture of either the medial collateral ligament (MCL) or the posterolateral structures.

POSITION CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

In 1963, Kennedy9 was the first to classify knee dislocations. He proposed a classification system based on the tibial position with respect to the femur. For example, an anterior knee dislocation implies that the tibia is positioned anterior to the femoral condyles. He identified five types of knee dislocation: anterior, posterior, lateral, medial, and rotatory. Rotatory dislocations were further subdivided into four groups: anteromedial, anterolateral, posteromedial, and posterolateral, with posterolateral being the most frequently described type of rotatory knee dislocation.5,6,14,15 This classification system has been widely utilized in the literature.*

The position classification system can help the physician plan a reduction maneuver for the dislocated knee. However, most knee dislocations can be easily reduced with longitudinal traction. The position classification system can also be useful to alert the clinician to the possibility of coexisting injuries. For example, several studies have shown a higher incidence of popliteal artery injury in anterior dislocations.5,8–10 However, vascular injury can occur with any position of knee dislocation; one must have a high index of suspicion for associated neurovascular injuries in any dislocated knee, regardless of position. Although knowing that an anterior dislocation carries an increased risk of vascular injury is helpful to the clinician, it does not give any information about what structures (ligamentous, neurovascular) have been injured and what treatment is required.

Critical Points POSITION CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

The position classification system is based on the tibial position with respect to the femur.

Uses

One example of the utility of the position classification system is the rare but important posterolateral dislocation (Fig. 26-3). The mechanism of injury is an abduction force to a flexed knee coupled with internal rotation of the tibia. This force causes the medial femoral condyle to “buttonhole” through the medial capsule and the MCL invaginates into the knee joint. The trapped condyle and MCL prevent closed reduction. The clinical hallmark of the posterolateral dislocation and irreducibility by closed means is a transverse furrow seen on the medial aspect of the knee.6,15 Peroneal nerve palsy, theoretically resulting from a traction injury to the nerve over the lateral femoral condyle, is frequently associated with this type of dislocation. Skin necrosis secondary to pressure from the medially displaced femur has also been reported. For a posterolateral knee dislocation, the position classification system alerts the clinician to the injured structures and the means of treating the injury.

ENERGY OF INJURY CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

Knee dislocations have also been classified by the degree of energy imparted to the knee joint. Most commonly, knee dislocations result from high-energy mechanisms such as motor vehicle wrecks, industrial accidents, and falls from a height (Fig. 26-4). The injury mechanisms in high-energy knee dislocations often cause significant associated head, chest, abdominal, and extremity injuries as well as soft tissue injury about the affected knee. Many of these injuries can be life-threatening, and their management takes precedence over the knee ligaments. Regardless of the energy of injury, the clinician must remain vigilant about the possibility of a popliteal artery injury in any knee dislocation. The orthopaedic surgeon must be alerted to the possibility of other life-threatening trauma in a patient with a knee dislocation. Conversely, trauma surgeons must include a gross assessment of knee stability in all patients involved in high-energy injury mechanisms. The risk of vascular and nerve injury is increased in high-energy knee dislocations.9,13,22,30

Knee dislocations can also occur from low-energy trauma such as that seen in sports activities or in minor falls. Sports in which knee dislocations are occasionally encountered include football, rugby, horseback riding, and skiing. Patients with dislocated knees from minor falls are often obese. Patients who sustain low-energy knee dislocations rarely have associated traumatic injuries. Although the risk of vascular injury is lower in low-energy mechanisms, the physician must still be vigilant in assessing the popliteal artery in all patients with a knee dislocation. In the past, knee dislocations have been described as low- or high-velocity injuries.22 It is our opinion that the term energy, rather than the term velocity, more accurately describes the injury mechanism.

ANATOMIC CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

A classification system for knee dislocations has been described and is based on what ligamentous structures are torn.28 The ligament anatomy of the knee is complex, with many injury patterns possible when a knee dislocation occurs.18,20,32 Conceptually, the knee can be separated into four simply identifiable structures: the ACL, the PCL, the medial ligamentous structures, and the posterolateral corner. The medial structures include the superficial and deep MCL as well as the posteromedial capsule. The posterolateral corner is primarily composed of the fibular (lateral) collateral ligament, the popliteofibular ligament, the popliteus tendon, and the lateral joint capsule. This simplistic representation of knee anatomy can be useful to the clinician in planning treatment of a dislocated knee.

Critical Points ANATOMIC CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

Advantages

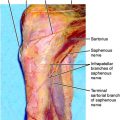

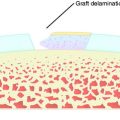

In order to classify a knee dislocation by the injured anatomy, it is important to obtain a thorough assessment of the injured knee. The clinician must perform a thorough physical examination of the knee on initial presentation to the emergency room or office. At a minimum, this should include a Lachman test, a posterior drawer test, varus and valgus stress testing at 0° and 30°, and a spin or dial test at 30° and 90°. A thorough neurovascular examination must also be performed. Any vascular abnormality warrants careful evaluation, which may include serial examinations, ankle brachial index evaluation, angiography, and/or popliteal artery exploration and repair/reverse saphenous vein graft. A complete neurologic examination may be difficult in a patient with head trauma, but in most cases, a gross assessment of tibial and peroneal nerve function can and should be obtained. As soon as the patient’s overall condition allows, we recommend obtaining a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the knee to better assess the degree and location of ligament injuries. Several authors3,17,19,31 have commented on the utility of the MRI in the evaluation of ligament injury in knee dislocations. Certain injuries (e.g., the presence of a PCL peel-off injury or a popliteus tendon avulsion) can be accurately detected preoperatively only by MRI. Knowing preoperatively which ligaments are torn and detecting the presence of avulsions can help the surgeon plan the number and types of allografts required and the fixation devices necessary to restore functional stability to the knee.19,21,31 The final and most critical assessment of knee ligament function occurs with an examination under anesthesia (EUA) at the time of knee reconstruction. The EUA provides a final assessment of the degree of translation, the presence of an endpoint on ligament stress testing, and the overall functionality of the specific ligamentous structure. Whereas MRI can identify which ligaments are injured, the EUA gives an accurate assessment of the functional stability of the injured knee ligaments.1,7,20,23,29 In the dislocated knee, partial ligament tears can often be treated nonoperatively. To summarize, the assessment of the dislocated knee consists of three parts: an initial examination in the trauma room or office, a preoperative MRI, and an EUA at the time of surgery.

The anatomic classification system of knee dislocation (KD) is a simple system based upon which ligaments are torn. Five major injury patterns can occur (Table 26-1). Injuries are classified by roman numerals; in general, higher-number injuries have sustained greater trauma than lower-number injuries. A KD I is a cruciate-intact knee dislocation and includes both PCL-intact and ACL-intact injuries (see Fig. 26-2). A KD II is a bicruciate injury with functionally intact collateral ligaments (Fig. 26-5). KD III, the most common injury pattern, involves tears of both cruciate ligaments and one of the collateral ligaments. These injuries are further subdivided into medial (KD III-M) (Fig. 26-6) or lateral (KD III-L) (Fig. 26-7) injuries. A KD IV involves complete disruption of all four major knee ligaments (Fig. 26-8). Finally, the KD V group is a knee dislocation with the presence of a major periarticular fracture and is described by other authors as a fracture-dislocation of the knee (Fig. 26-9).12,21 Fracture-dislocations of the knee involve a ligamentous injury to the knee in association with a major fracture of the tibial plateau or femoral condyles that further destabilizes the knee joint. Although avulsion injuries are frequently seen in purely ligamentous knee dislocations (arcuate avulsion fractures, tibial spine avulsions, or segond fractures), they should be classified as a ligamentous injury in one of the first four categories, despite the small fracture present.4,25

| Class | Injury |

|---|---|

| KD I | PCL or ACL intact KD, Variable collateral involvement |

| KD II | Both cruciates torn, collaterals intact |

| KD III | Both cruciates torn, one collateral torn, Subset M or L |

| KD IV | All four ligaments torn |

| KD V | Periarticular fracture-dislocation |

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; KD, knee dislocation; L, lateral; M, medial; PCL, posterior cruciate ligament.

FIGURE 26-5 Lateral radiograph demonstrates a bicruciate injury with functionally intact collateral ligaments (KD II).

FIGURE 26-6 AP radiograph (A) and MRI (B) of a bicruciate injury with involvement of the MCL (KD III-M).

FIGURE 26-7 Lateral radiograph (A) and MRI (B) of a bicruciate injury with involvement of the FCL (KD III-L).

FIGURE 26-8 AP radiograph (A) and MRI (B) demonstrate complete disruption of all four major knee ligaments (KD IV).

Finally, the anatomic classification system will help the clinician predict outcomes in the treatment of dislocated knees. On average, knees with a higher roman numeral classification will have inferior outcome scores. Likewise, it has been shown that KD III-L injuries fare worse than KD III-M injuries.3,28 Knee dislocations with neurovascular injuries (subtypes C or N) are also more likely to have unsatisfactory outcome measurements. KD V injuries are associated with a high complication rate related to the increased incidence of arterial injury, inadequate fracture reduction, or difficulty in achieving a satisfactory ligament reconstruction.

1 Almekinders L., Logan T. Results following treatment of traumatic dislocations of the knee joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;284:203-207.

2 Cooper D.E., Speer K.P., Wickiewicz T.L., et al. Complete knee dislocation without posterior cruciate ligament disruption: a report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop. 1992;284:228-233.

3 Eastlack R.K., Schenck R.C.Jr., Guarducci C. The dislocated knee: classification, treatment, and outcome. US Army Med Dep J. 1997;11(12):2-9.

4 Frassica F.S., Franklin H.S., Staeheli J.W., et al. Dislocation of the knee. Clin Orthop. 1992;263:200-205.

5 Green N.E., Allen B.L. Vascular injuries associated with dislocation of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:236-239.

6 Hill J.A., Rana N.A. Complications of posterolateral dislocation of the knee: case report and literature review. Clin Orthop. 1981;154:212-215.

7 Honton J.L., Le Rebeller A., Legroux P., et al. Traumatic dislocation of the knee treated by early surgical repair. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1978;64:213-219.

8 Jones R.E., Smith E.C., Bone G.E. Vascular and orthopaedic complications of knee dislocation. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979;149:554-558.

9 Kennedy J.C. Complete dislocation of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45:889-904.

10 Meyers M., Harvey J.P. Traumatic dislocation of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:16-29.

11 Meyers M., Moore T., Harvey J.P. Follow-up notes on articles previously published in The Journal: traumatic dislocation of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:430-433.

12 Moore T.M. Fracture-dislocation of the knee. Clin Orthop. 1981;156:128-140.

13 Muscat J.O., Rogers W., Cruz A.B., et al. Arterial injuries in orthopaedics: the posteromedial approach for vascular control about the knee. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:476-480.

14 O’Donoghue D. Treatment of Injuries to Athletes, 2nd ed., Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1970:508-510.

15 Quinlan A.G., Sharrard W.J.W. Posterolateral dislocation of the knee with capsular interposition. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1958;40:660-663.

16 Reckling F.W., Peltier L.F. Acute knee dislocations and their complications. J Trauma. 1969;9:181-191.

17 Reddy P.K., Posteraro R.H., Schenck R.C.Jr. The role of MRI in evaluation of the cruciate ligaments in knee dislocations. Orthopedics. 1996;19:166-170.

18 Schenck R.C. Knee dislocations. Instr Course Lect. 1994;43:127-136.

19 Schenck R.C., DeCoster T., Wascher D. MRI and knee dislocations. Sports Med Rep. 2000;2:89-96.

20 Schenck R.C., Hunter R., Ostrum R., et al. Knee dislocations. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:515-522.

21 Schenck R.C., McGanity P.L.J., Heckman J.D. Femoral-sided fracture-dislocations of the knee. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11:416-421.

22 Shelbourne K.D., Porter D.A., Clingman J.A., et al. Low velocity knee dislocations. Orthop Rev. 1991;11:995-1004.

23 Shelbourne K.D., Pritchard J., Rettig A.C., et al. Knee dislocations with intact PCL. Orthop Rev. 1992;21:607-611.

24 Shields L., Mitral M., Cave E.F. Complete dislocation of the knee: experience at the Massachusetts General Hospital. J Trauma. 1969;9:192-215.

25 Sisto D.J., Warren R.F. Complete knee dislocation. Clin Orthop. 1985;198:94-101.

26 Stannard J.P., Sheils T.M., Lopez-Ben R.R., et al. Vascular injuries in knee dislocations following blunt trauma: evaluating the role of physical examination to determine the need for arteriography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:910-915.

27 Taylor A.R., Arden G.P., Rainey H.A. Traumatic dislocation of the knee: a report of forty-three cases with special references to conservative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1972;54:96-109.

28 Walker D.N., Hardison R., Schenck R.C. A baker’s dozen of knee dislocations. Am J Knee Surg. 1994;7:117-124.

29 Wascher D.C. High-velocity knee dislocation with vascular injury: treatment principles. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19:457-477.

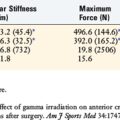

30 Wascher D.C., Becker J.R., Dexter J.G., et al. Reconstruction of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments after knee dislocation: results using fresh-frozen nonirradiated allografts. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:189-196.

31 Wascher D.C., DeCoster T.A., Schenck R.C. 10 commandments of knee dislocation. Orthopedics Spec Ed. 2001;7(2):28-31.

32 Wascher D.C., Dvirnak P.C., DeCoster T.A. Knee dislocation: initial assessment and implications for treatment. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11:525-529.