CHAPTER 12 CIVILIAN HOSPITAL RESPONSE TO MASS CASUALTY EVENTS

On February 20, 1993, six people were killed and more than 1000 injured when a bomb exploded at the World Trade Center in New York City. Two years later, on April 19, 1995, 168 people died and 850 were injured when a bomb destroyed the Alfred P. Murrah Building in Oklahoma City. On September 11, 2001, 2986 people lost their lives when the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center collapsed after two hijacked civilian airliners were piloted into the towers by Islamic fundamentalists. These events served as a stimulus to the medical community to better prepare for mass casualty events caused by attacks with both conventional and unconventional weapons. The tsunami that destroyed coastal areas in Southern Asia on December 26, 2004 and the flooding of New Orleans after hurricane Katrina in September 2005 demonstrated inadequate responses to loss of infrastructure caused by natural disasters. A thoughtful and well-rehearsed disaster plan is essential to an effective response.

KEY DEFINITIONS

Patients are triaged into four categories at the scene: minor, delayed, immediate, and dead. In military triage systems, a fifth category, expectant care, is used for patients with a small chance of survival who would use scarce resources to such an extent as to adversely affect the chance of survival of other more salvageable patients. This category is rarely used in civilian situations as mobilization of additional personnel resources is usually possible. Numbers, colors, or symbols may be used to denote the categories (Table 1). “Undertriage” refers to assignment of patients to a level of care inadequate for their level of injury. An under-triage rate greater than 5% is unacceptable as it may lead to unnecessary morbidity and mortality in severely injured patients. “Overtriage” refers to assignment of patients to a level of care greater than required for their level of injury. An overtriage rate of 50% is considered acceptable to minimize undertriage. Excessive overtriage at the scene threatens the response of the entire system due to expenditure of limited resources on the wrong patients.

| Minor—Green | Delayed care/can delay up to 3 hours |

| Delayed—Yellow | Urgent care/can delay up to 1 hour |

| Immediate—Red | Immediate care/life-threatening |

| Dead—Black | Victim is dead/no care required |

Adapted from Los Angeles Community Emergency Response Team.

PREHOSPITAL CARE IN MASS CASUALTY EVENT

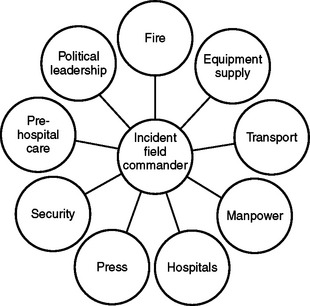

The response to a mass casualty event requires the coordinated effort of many agencies with disparate cultures, command structures, and even communications equipment (Figure 1). Appropriate agencies should submit to the authority of the incident field commander at the scene. Prior joint training can break down these barriers and improve overall response to the event.

HOSPITAL TRIAGE

If either a large number of casualties suddenly arrive without warning, or the hospital is informed of their impending arrival, the hospital should initiate its mass casualty plan. In a true mass casualty event, all area hospitals must participate in the care of victims to avoid exhaustion of the resources of any one facility. The common goal is salvaging as many lives as possible. A contingency plan for patients not involved in the mass casualty event must be in place as part of emergency preparedness. This plan permits the hospital to convert to mass casualty mode in a short period of time.

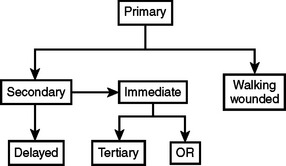

The initial hospital triage (Figure 2) should occur outside the ED as patients arrive by ambulance. Ideally, ambulances should pass through a security checkpoint prior to entrance to the hospital grounds to identify terrorists or ordinance that may be on board. Initial triage need not be done by a surgeon, but should be done by a highly experienced clinician. If possible, the walking wounded should be escorted through a separate entrance.

As soon as stretcher patients enter the ED, a senior surgeon should triage each patient to either immediate or delayed care (see Figure 2). The immediate treatment area should be reserved for salvageable patients with life-threatening problems. This area should have enough space for equipment and provide a one-way flow of traffic. The following personnel should be present at each bed in the immediate care area: a senior surgeon for decision making, an anesthesiologist to provide airway control, two ED or critical care nurses, and a junior surgeon for vascular access and tube thoracostomy as necessary.

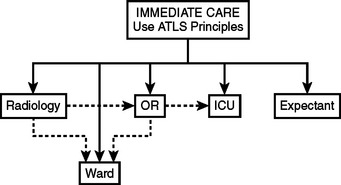

Treatment in the immediate care area is based upon the principles of advanced trauma life support. The goals of therapy in the immediate care area are airway control, ventilation, cessation of external hemorrhage, vascular access, and rapid transfer of the patient to the next appropriate treatment station, usually the intensive care unit (ICU) or the operating room (OR), for completion of the primary and secondary surveys and further diagnostic or therapeutic interventions. Factors affecting the decision as to where to perform the secondary survey and the patient’s ultimate disposition include the patient’s condition and the number of immediate care patients (Figure 3). This decision should be made by a senior surgeon.

HOSPITAL EMERGENCY INCIDENT COMMAND SYSTEM

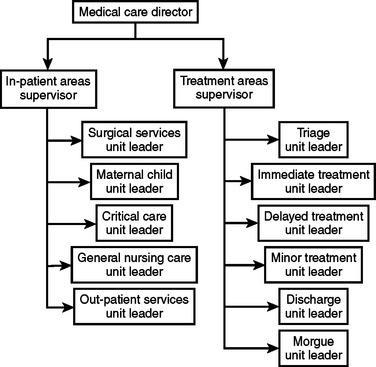

The basic principle of HEICS is that one individual supervises no more than five people and reports to only one person. A senior surgeon is the ideal incident commander. This system allows for efficient and manageable lines of communication and easy accountability. There are four main section chiefs: planning, logistics, finance, and operations. The operations chief has overall responsibility for the triage of victims and their clinical care, and potential coordination with other area hospitals (Figure 4).

CAUSES OF MASS CASUALTY EVENTS

Conventional Weapons/Blast Injury

Physics of Blast Wave

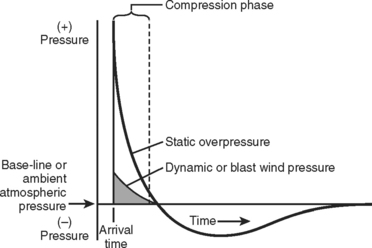

Energy is transferred from the explosion to the atmosphere generating a supersonic blast wave that rapidly slows to the speed of sound (Figure 5). In an open space, the blast wave dissipates rapidly. In a closed space, however, the blast wave reverberates against a solid wall increasing the force of the wave. For this reason, the mortality rate and severity of injuries of the victims are significantly higher in closed-space as opposed to open-space explosions.

A primary blast injury occurs when the pressure wave directly hits the body surface. Gas-filled organs are particularly susceptible to injury, such as the lungs, intestines, and ears. Damage to the eye and brain may also occur. Specific injuries are summarized in Table 2. A secondary blast injury occurs as a result of flying debris and bomb fragments. It can cause both blunt and penetrating injury and can affect any part of the body. Tertiary blast injury occurs as a result of blunt trauma as victims are thrown against solid objects by the blast impulse. A quaternary blast injury encompasses miscellaneous explosion-related injuries such as burns, crush injuries, and impalements. Illnesses directly related to the blast such as post-traumatic stress disorder, asthma exacerbations, angina, infection, or other complications secondary to inhalation of toxic fumes are also classified as quaternary blast injuries.

| Organ System | Effect |

|---|---|

| Auditory | Ruptured tympanic membrane (almost always seen with blast lung), ossicular disruption, foreign body |

| Eye, orbit, face | Ruptured globe, foreign body, fracture, air embolus |

| Respiratory | Blast lung, pulmonary contusion, pneumothorax, left-sided air embolism, aspiration |

| Circulatory | Myocardial contusion, myocardial infarction (air embolism), hemorrhagic shock |

| Central nervous system | Closed or open head injury, stroke or spinal cord injury from air embolism, spinal cord injury from blunt trauma |

| Renal | Contusion, laceration, acute renal failure from hypotension or rhabdomyolysis |

| Gastrointestinal | Bowel perforation, hemorrhage, solid organ injury, mesenteric ischemia (air embolus) |

| Extremity | Amputation, crush, fracture, compartment syndrome, burns, vascular injury. Most common system needing operative intervention |

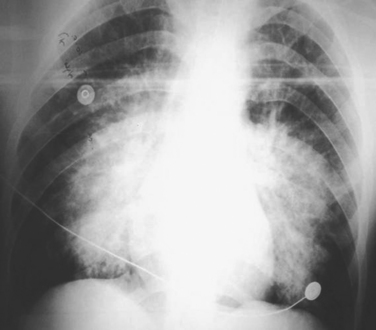

Blast lung injury, the most serious common primary blast injury, is a direct result of injury to the pulmonary parenchyma due to barotrauma. Many victims of blast lung injury are dead at the scene. The clinical presentation is similar to pulmonary contusion. The most common symptoms and signs are hemoptysis and hypoxia leading to dyspnea, tachypnea, and poor compliance. Unlike pulmonary contusion, blast lung injury does not usually have associated rib fractures. Typical chest radiographic findings (Figure 6) include a “butterfly” pattern of infiltrates, pneumomediastinum, hemothorax, and pneumothorax.

Biological Agents

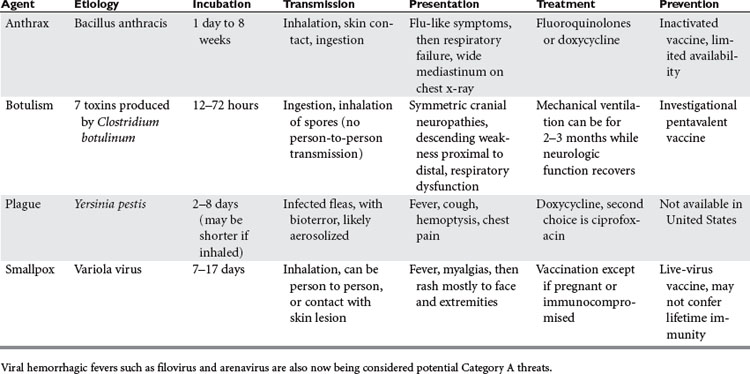

The United States categorizes agents based on their risk to national security and the safety of its citizens. Category A agents, the highest risk category, can be easily disseminated, have a highmortality rate, may cause panic, and require a major public health effort to contain the spread of disease. The four major agents in Category A, their characteristics, and management strategies are listed in Table 3.

Chemical Agents

Radiation Injuries

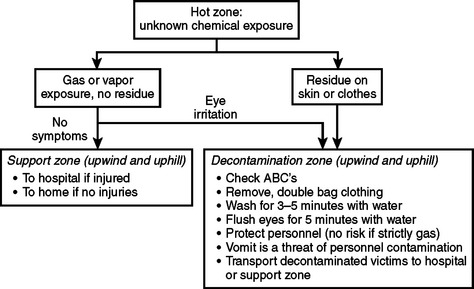

The response to release of radiation should include protection of first responders and hospital personnel. At the scene, all efforts should be made to put emergency equipment and decontamination zones upwind and uphill. Responders should wear full masks and protective garments. Individuals without life-threatening blast injuries should be decontaminated at the scene prior to being transported to a hospital.

California Emergency Medical Services Authority: Hospital Incident Command System, 1998. Available at www.HEICS.com/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Available at www.cdc.gov/

Community Emergency Response Team—Los Angeles Available at: www.cert-la.com/triage/

Einav S, Feigenberg Z, et al. Evacuation priorities in mass casualty terror-related events. Implications for contingency planning. Ann Surg. 2004;39(3):304-310.

Frykberg ER. Principles of mass casualty management following terrorist disasters. Ann Surg. 2004;239:319-321.

Hirshberg A, Holcomb J, Mattox K. Hospital trauma care in multiple-casualty incidents: a critical review. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:647-652.

Kennedy K, Aghbabian RV, et al. Triage: techniques and applications in decision making. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28(2):136-144.

Klein JS, Weigelt JA. Disaster management: lessons learned. Surg Clin North Am. 1991;71:257-266.

Lee S, Morabito D, et al. Trauma assessment training with a patient simulator: a prospective, randomized study. J Trauma. 2003;55(4):651-657.

Leibovici D, Gofrit O, et al. Blast injuries: bus versus open air bombings-a comparative study of injuries in survivors of open-air versus confined-space explosions. J Trauma. 1996;41:1030-1035.

U.S. Department of Defense Available at www.defenselink.mil/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Available at www.hhs.gov/

U.S. Department of Homeland Security Available at www.dhs.gov/dhspublic/

Waeckerle JF. Disaster planning and response. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:815-821.