Chapter 118 Cingulotomy for Intractable Psychiatric Illness

Historical Developments

For millennia, physicians have attempted to treat diseases of the mind with surgery1–7 initially in the form of cranial trepanations. In the modern era, psychiatric neurosurgery was first proposed by the Portuguese neurologist, Egas Moniz.8 Initially, Moniz injected alcohol into the white matter of the frontal lobes of institutionalized patients and while this early experience received only cautious support, the concept of a surgical therapy for psychiatric patients was rapidly adopted, culminating in Moniz being awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1949. One of the most enthusiastic proponents of this new therapy was Walter Freeman9 in the United States, who championed prefrontal lobotomy. At first his technique involved bilateral coronal sectioning of the frontal lobes via burr holes and later by a transorbital approach. These early surgical techniques were crude and associated with major morbidity and mortality as high as 10%. Complications included severe cognitive impairment, personality changes, intracranial hemorrhage, and seizures.10 The patients were believed to be “no longer distressed by their mental conflicts but also seem to have little capacity for any emotional experience.” Standard intelligence quotient (IQ) tests, however, revealed no significant postoperative deficits, and Freeman along with other practitioners at the time considered the side effects acceptable.

Surgery for intractable psychiatric illness thus became widely accepted and was used for a variety of diagnoses, including major depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and schizophrenia. Between 1942 and 1954, more than 10,000 cases in England and Wales and more than 18,000 cases in the United States were performed.10 However, there was much controversy among neurologists, neurosurgeons, and psychiatrists who had reservations regarding the scientific, ethical, and technical aspects of psychosurgery. This controversy prompted more rigorous clinical trials with a goal to reduce lesion size to more anatomically specific brain regions.

Stereotactic neurosurgical techniques were introduced in 1947, to create accurate lesions in cortical and subcortical structures, and numerous target areas were identified, including the cingulate cortex. The methodical study of the cingulate cortex in primates was pioneered by John Fulton.11 Fulton12 was the first to suggest that the anterior cingulum would be an appropriate target for psychiatric neurosurgical intervention, and cingulotomy was initially carried out as an open procedure.13,14 Whitty in 1955 described 35 such patients of open cingulectomy,15 with most of the surgery being carried out by the late Sir Hugh Cairns of Oxford. Patients were selected based on predominant symptoms of either anxiety or obsessive behavior. The procedures were successful on the whole, with the outcome described as a “slight loss of inhibition and a reduction in tension and in the persistence of emotional and cognitive activity.”15 Foltz and White16 reported their experience with stereotactic cingulotomy for intractable pain, and noted that optimal results were achieved in patients with concurrent anxiety-depressive states. Ballantine and colleagues17 subsequently demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of cingulotomy in a large number of patients, and it has been the surgical procedure of choice in North America over the last 3 decades. In Europe, alternative targets were being used, such as subcaudate tractotomy,18 anterior capsulotomy, and limbic leucotomy (a combination of cingulotomy and subcaudate tractotomy).19

Concurrent to the development of stereotactic surgical techniques and safer more discrete lesions, psychotropic drugs were introduced that offered a safe alternative therapy and new hope. Chlorpromazine became available for use in the United States as an antipsychotic in 1954, and approval of major antidepressant medications soon followed. Pharmacotherapy was rapidly embraced by the psychiatric community, and consequently there was a dramatic decrease in the demand for surgical intervention. Currently the accepted therapeutic approach to most psychiatric disease involves a combination of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy. Despite these modern treatment methods, many patients fail to respond adequately and remain severely disabled. In these patients, surgical intervention may still be considered appropriate if the therapeutic result and overall level of functioning are improved. Although our understanding of the anatomy and physiology of surgical lesions has improved and our ability to place discrete and accurate lesions in targets of interest has progressed, the debate and controversy in this area continue.

Functional Neuroanatomic Basis for Cingulotomy

The cingulate (from the Latin for belt) gyrus lies on the medial surface of each cerebral hemisphere adjacent to the falx cerebri and forms part of the “limbic lobe.” The underlying subcortical white matter, the cingulum bundle, connects the cingulate gray matter with various regions, including prefrontal cortical areas, basal ganglia, thalamus, and mesial temporal structures, as well as connecting the anterior perforated substance with the parahippocampal gyrus.7,20,21 Histologically, the cingulate cortex consists of mesocortex and a transitional cortical architecture between the six-layer neocortex and the three-layer paleocortex.22 Based on function and architecture, the cingulate cortex is often divided into an anterior and posterior division. The anterior division is involved in executive functions, whilst the posterior part is sensory and limbic related. The anterior cingulate may be further subdivided into dorsal and ventral parts, involved in cognitive and affective functions respectively.

In 1937, Papez23 published “A Proposed Mechanism of Emotion,” in which he postulated that a reverberating circuit in the brain might be responsible for emotion, anxiety, and memory. The anatomic components of this circuit consisted of the hypothalamus, septal area, hippocampus, mammillary bodies, anterior thalamic nuclei, cingulate gyri, and their interconnections. This rudimentary limbic system was subsequently expanded to include paralimbic structures, including orbitofrontal, insular and anterior temporal cortices, the amygdala, and dorsomedial thalamic nuclei.24 The hypothalamus, a central component in this system, controls autonomic function, and these functions in humans are often accompanied by subjective experiences and behavioral patterns. Stimulation of the hypothalamus in animals produces autonomic, endocrine, and complex motor effects, which supports the idea that the hypothalamus integrates and coordinates the behavioral expression of emotional states.25 The neural outflow from the hypothalamus can be modulated by cortical and brainstem inputs, and the limbic system represents a direct pathway to the hypothalamus. Neocortical areas are connected to the limbic system proper by paralimbic structures.26 The limbic system appears to interconnect visceral and somatic stimuli with higher cortical functions and in this way may “add an emotional component to the psychic process.”23

Although the exact neuroanatomic and neurochemical basis of emotion in health and disease remains undefined, there is evidence that the limbic system and its interconnections with the basal ganglia and forebrain play a central role in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Electrical stimulation of specific areas within the limbic system (i.e., the anterior cingulate) has been shown in humans to alter autonomic responses and anxiety levels27,28 and can cause movements in awake patients that resemble compulsive actions.29 Neuroimaging studies also implicate a circuit composed of orbitofrontal cortex, striatum, thalamus, and anterior cingulate cortex in the pathophysiology of OCD. Abnormalities of glucose metabolism have been found in the caudate nucleus, orbitofrontal cortex, and cingulum in patients with OCD on positron emission tomography (PET).30,31 Specialized PET images taken of patients during obsessive states reveal uniform hypermetabolism in the caudate nucleus, anterior cingulum, midfrontal cortex, and left thalamus, all structures connected with the limbic system.32 Similarly, PET studies have shown that reduced glucose metabolism in the lateral frontal cortex is a correlate of the depressive state in certain patients.33

The cortical-striatal-pallido-thalamic connections that have been well characterized for the control of motor function may explain some features of OCD. Modell et al.34 proposed that this network consists of two components: an orbitofrontal-thalamic loop mediated by the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate and an orbitofrontal-striatal-thalamic loop mediated by various transmitters, including glutamate, dopamine, serotonin, γ-aminobutyric acid, and glutamate. With this model, overactivity of the orbitofrontal-thalamic loop results in obsessive compulsive behavior. Neurochemical models suggest that affective and anxiety disorders may be mediated via monoaminergic systems. In particular, the serotoninergic system has received emphasis with respect to OCD. Because of the diffuse nature of the monoaminergic projections and their role as neuromodulators, however, these models are not particularly instructive in terms of the functional neuroanatomy relevant to different neurosurgical treatments as they are currently used.

Although the exact neuroanatomical and neurochemical mechanisms underlying depression, OCD, and other anxiety disorders remain unclear, it is appealing to believe that these psychiatric disorders might reflect a final common pathway of limbic dysregulation, which can be modulated surgically. Neurobiological models of anxiety and affective disorders have also emphasized the fundamental role of the limbic system and its related structures.34–36 Almost all psychosurgical procedures have been directed at some component within this system, giving rise to the less emotive term of limbic system surgery.

Indications

Cingulotomy has been performed successfully for a number of psychiatric disorders including major affective disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, addiction, as well as chronic pain. Patients considered for cingulotomy should have demonstrated a severe, chronic, disabling, and treatment-refractory psychiatric illness. Illness severity should be manifest in terms of subjective distress and a decrement in psychosocial functioning. Chronicity refers to the enduring nature of the illness and in some cases may be less important than severity. The illness must also be refractory to systematic trials of pharmacologic, psychological, and, when appropriate, electroconvulsive therapy before considering neurosurgical intervention.

The major psychiatric diagnostic groups that might benefit from cingulotomy are1 chronic anxiety states, including OCD, and2 major affective disorder (i.e., major depression or bipolar disorder). Patients who present with mixed disorders demonstrating a combination of symptomatology of anxiety, depression, and OCD, may still be candidates for psychosurgery. Schizophrenia is currently not considered an indication for cingulotomy. Relative contraindications include a history of a significant personality disorder, other axis II symptoms substance abuse, or acute suicidality. Patient selection is probably the single most important issue in psychiatric surgery, and although the patient undergoes a multidisciplinary review, the responsibility of selection for surgery rests with the psychiatrist, who may also be responsible for long-term postsurgical management.

Surgical Technique

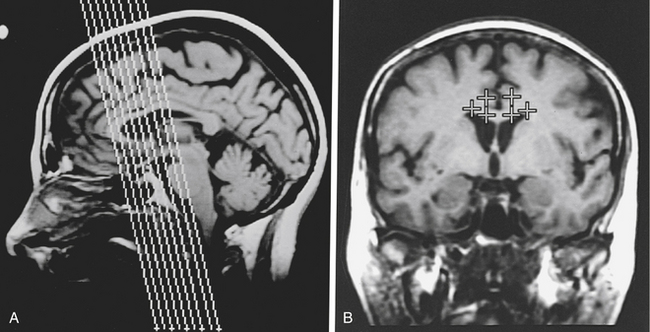

Briefly, an MR stereotactic compatible frame is fixed to the patient’s cranial vault under intravenous sedation and after infiltration of the pin insertion sites with local anesthesia. Oblique coronal MR images are then obtained and typically, target coordinates are calculated for a point in the anterior cingulate gyrus 2 to 2.5 cm posterior to the tip of the frontal horn, 7 mm from the midline, and 2 to 3 mm above the corpus callosum bilaterally (Fig. 118-1).

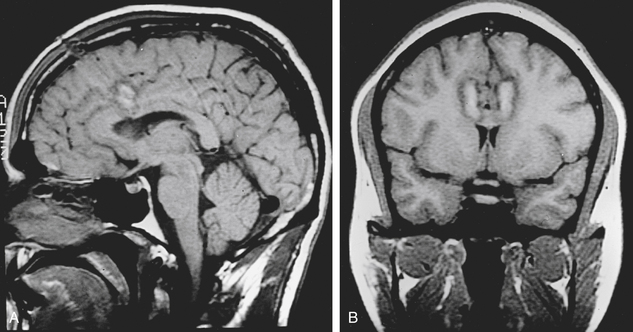

After the target coordinates are calculated, the trajectory is optimized and entry point noted. The patient is positioned on the operating table and the stereotactic frame is secured to the table. A supine or semireclining position on the operating table is suitable with the head positioned low enough to prevent air embolism. Under local anesthesia, the skin is then incised. A variety of skin incisions may be chosen, such as bilateral 1-cm straight incisions or a bicoronal skin incision. Intracranial access is gained via bilateral burr holes with a perforator 15 to 25 mm from the midline. In general, a handheld drill is preferred to a pneumatic-powered drill to minimize patient anxiety. The dura is opened and an entry point chosen to avoid cortical vessels. A standard thermocoagulation electrode (Radionics, Inc., Burlington, MA) with a 10-mm uninsulated tip is inserted to the target and heated to 85°C for 90 seconds. After adequate cooling, the electrode is then withdrawn 5 to 10 mm, and a second lesion is made, using the same lesion parameters to ensure complete ablation of the cingulate gyrus. This results in a lesion of approximately 1 to 2 cm in vertical height and 8 to 10 mm in diameter in the anterior cingulum (Fig. 118-2). The procedure is then performed in an identical fashion on the opposite side.

Long-Term Multidisciplinary Management

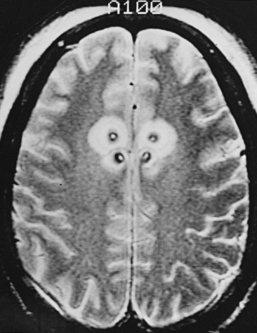

Postcingulotomy patients require regular long-term psychiatric management to readjust pharmacotherapy doses and proceed with other conventional therapies, such as psychotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy, which are often more effective postoperatively. Cingulotomy should not be considered curative but rather as an adjunct to optimal psychiatric treatment. The support of family members and close friends is essential to the successful management of postcingulotomy patients. They provide emotional support for the patient and can alert the psychiatrist to any abnormal behavior or symptoms postoperatively. Up to 50% of cingulotomy patients require a repeat cingulotomy. Repeat surgery lesion enlargement is considered if there has been minimal or suboptimal response to the initial surgery at the 6-month follow-up. Multiple cingulotomies can be performed safely after adequate time has elapsed between procedures (Fig. 118-3). Advanced neuroimaging techniques may be useful in these patients to determine degree of cingulum-fiber-bundle disruption. Repeat lesions are made anterior to the initial lesion but not more than 2.5 cm posterior to the tip of the frontal horn to avoid injury to the premotor area. Occasionally, a third cingulotomy can be considered if the results of the initial two operations provided temporary benefit. In those scenarios, a limbic leucotomy, which entails addition of a subcaudate tractotomy lesion, provides another surgical option.

Cingulotomy for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive compulsive disorder has been one of the primary indications for cingulotomy. Although many patients experience an immediate reduction in anxiety, there is generally a delay to the onset of beneficial effect on both obsessive compulsive and depressive symptoms. This latency has been observed by many centers and may suggest that the beneficial effects are related not only to interruption of neural pathways but also to reorganization of neural pathways after injury. This delay in treatment effect may take up to 3 to 6 months, and the patient and caregivers should be made aware of this prior to surgery.

Ballantine et al.17 presented the retrospective review of results of bilateral cingulotomy in 198 patients suffering from a variety of psychiatric disorders. This cohort came from a larger group of 696 cingulotomies in 465 patients, of whom 273 were operated on for psychiatric disease. Adequate follow-up data were available on 198 of 273 patients and included questionnaires, review of clinical records, and outpatient visits. The psychiatric diagnosis was reclassified retrospectively with newer DSM criteria. A 5-point clinical rating scale of outcome was used. This scale defined postoperative results as follows: 5, normal and on no treatment; 4, functionally normal but requiring medication or psychotherapy; 3, much improved; 2, slight improvement; 1, no change; 0, worse; and S, suicide. Any patient with a postoperative result of 3 (much improved) or better was considered a successful outcome. The outcome was rated by the referring clinicians and is open to rater bias but still has some validity. With a mean follow-up of 8.6 years, 56% of patients with OCD were found to have experienced worthwhile improvement.

Using the identical outcome measures,17 a more recent retrospective study of MR-guided stereotactic cingulotomy37 yielded similar success rates underscoring the positive bias that may occur with subjective outcome rating scales. A more detailed retrospective study evaluating cingulotomy in 33 patients with refractory OCD using unbiased observers has also been reported. Outcome scores included the Massachusetts General Hospital Visual Analog Assessment scale, Maudsley Obsessional Compulsive Inventory, YBOCS, Clinical Global Improvement (CGI), and BDI. In this study, at least 25% to 30% of patients benefited substantially from cingulotomy.38 Baer et al. reported prospective long-term follow-up on 18 patients who underwent cingulotomy for intractable OCD.39 Preoperative evaluation included administration of a YBOCS, YBOCS symptoms checklist, CGI, and BDI. At the 6-month follow-up, the YBOCS, Massachusetts General Hospital Visual Analog Assessment scale, CGI, BDI, and Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) were performed and treatment “responder” status was determined if a greater than 35% improvement on YBOCS and a CGI of 1 or 2 was established. Patients who had a greater than 35% improvement on YBOCS or a CGI of 1 or 2 were considered possible responders. Five patients met the criteria for treatment responders, and two others were considered possible responders. The entire cohort improved significantly in terms of functional status, and no significant adverse effects were encountered. Evidence of clinical efficacy of surgical therapy does not suffice, for it must also be proven safe.

A quantification of surgical risk is necessary to determine the benefit–risk profile for the patient and this information needs to be explained in detail preoperatively. In more than 900 cingulotomies performed at the Massachusetts General Hospital since 1962, there have been no deaths and only two infections. Two acute subdural hematomas occurred early in the series secondary to laceration of a cortical artery at the time of introduction of ventricular needles, and only one patient suffered permanent neurologic impairment.40 Corkin et al. reported 34 patients who underwent cingulotomy and demonstrated no significant behavioral or intellectual deficits as a result of the cingulate lesions.41

Other targets have been used for patients with severe OCD and by applying the Pippard Postoperative Rating Scale42 with patients in categories A (symptom-free) and B (much improved with no additional treatment necessary) considered satisfactory outcomes, then subcaudate tractotomy was effective in 50%, cingulotomy in 56%, limbic leucotomy in 61%, and capsulotomy in 67% of OCD patients. In patients with major affective disorder, subcaudate tractotomy was effective in 68%, cingulotomy in 65%, limbic leucotomy in 78%, and capsulotomy in 55%. Kullberg compared cingulotomy and capsulotomy in the treatment of 26 patients in a randomized fashion.43 Six of 13 capsulotomy patients and 3 of 13 cingulotomy patients were improved, although transient deterioration in mental status was more pronounced after capsulotomy compared with cingulotomy. Similar findings were noted in a smaller study of 4 patients.44 Two prospective studies were compared in an attempt to evaluate the efficacy of cingulotomy and capsulotomy in OCD.45 Forty-five percent of capsulotomy patients and 39% of cingulotomy patients demonstrated improvement. Again, procedure-related side effects were more evident after capsulotomies.

The superiority of any one of the above targets for OCD is not clearly established, although individual centers prefer certain procedures over others. The clinical outcome appears similar but cingulotomy has been the more prevalent treatment in the United States, whereas in Europe, capsulotomy and limbic leucotomy are preferred. This is changing with the more common use of DBS for OCD. Regardless of the choice of procedure, surgical failures should be investigated, and if the lesion size or location is suboptimal, consideration should be given to a repeat procedure. In 5 of the 24 patients in the series by Mindus and Nyman,46 a significant correlation was found between neuroradiologic ranking of a target site and the psychiatric outcome, suggesting that the site and extent of lesion may be important influences on outcome. Further prospective trials using standardized clinical instruments with long-term follow-up are needed to validate what have over decades been promising results of cingulotomy for OCD.

Cingulotomy for Depression

Major depressive disorder is an extremely disabling condition that poses a significant health burden on society. The pathophysiologic basis of this disorder is not fully understood; however, numerous surgical treatment options have been developed and applied for decades. Advances in pharmacotherapeutic options have significantly improved treatment of depression, although treatment-resistant depression (failure of antidepressant medication and electroconvulsive therapy) affects 10% to 20% of these patients. Psychiatric neurosurgery offers numerous options for treatment including stereotactic lesional surgery, vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) and DBS. Lesional surgery may involve anterior cingulotomy, subcaudate tractotomy, limbic leucotomy, and anterior capsulotomy.53–55 Shields et al. reported long-term outcome data of ablative surgery in treatment resistant depression.54 Of 33 patients in the series, 17 underwent placement of a single stereotactic cingulotomy lesion without other ablative procedures. Forty-one percent were classified as responders and 35% as partial responders. The remaining 16 patients who did not respond to initial lesioning underwent either repeat cingulotomy or subcaudate tractotomy with 25% responders and 50% partial responders. Therefore, the overall response rate to surgery was 75%. Clinical effects may take months to manifest, which suggests that target ablation may have an effect on neuroplasticity and limbic networks rather than being a direct effect of ablating the target lesion.

In Ballantine’s study,17 most of the depressed patients (83%) were suicidal, and 9% of patients committed suicide during the follow-up period. This annual suicide rate postcingulotomy of 1%, however, is less than the expected average annual suicide rate for severely depressed patients.56

Patient selection for cingulotomy remains a difficult clinical issue, although advances in imaging may be able to predict surgical response. Dougherty et al.57 were able to show that selective hypermetabolism in the subgenual cingulate cortex demonstrated with positron emission tomography (PET) can predict response to cingulotomy in a linear correlation. It may be that stereotactic ablation of hypermetabolic regions simply “switch off” pathologically active structures and their “downstream” action although the exact mechanisms are likely much more complex.

Cingulotomy for Addiction

Addiction is defined as a chronic relapsing disorder characterized by a pronounced physical and psychological substance or drug dependence, resulting in a withdrawal syndrome when intake ceases.47 Disease progression typically starts with “social” substance use, followed by compulsive use and subsequently dependence with the consequence of withdrawal. During intake of a psychoactive substance, dopamine is released in the nucleus accumbens.48 The result is an activation of the reward system, a circuit that involves dopaminergic neurons which project from the ventral tegmentum to the nucleus accumbens, amygdale, and prefrontal and cingulate cortices.49,50 Positive reinforcement as a result of the “high” that is experienced as well as negative reinforcement in the form of withdrawal symptoms disrupt the biological reward system. Dopaminergic dysfunction of the prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices have been linked to an impairment of decision-making and inhibitory control. As a result of this complex pathophysiology and the multiple target areas involved in the neural circuits of addiction, psychosurgery has involved intervention into multiple target areas including the hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens and cingulate cortex.

In 1973, Balasubramaniam et al.51 described 28 patients with pethidine or morphine addictions who underwent bilateral cingulotomy with success in 22 patients. Results in a larger series followed52 with a series of 73 patients, with treatment success in 80% of morphine addicts, 90% of meperidine addicts, and 68% of alcohol addicts. More recently, a series of bilateral cingulotomy in heroin addicts reported a 45% abstinence of drugs at 2-year follow-up. Retrospective surgical series and case reports form the majority of literature in this field. Randomized trials would add increased value to current evidence for the success of this procedure and in addition to efficacy, side effects need to be quantified in a robust manner.

Cingulotomy for Other Psychiatric Indications

The large experience of cingulotomy at the Massachusetts General Hospital for a variety of psychiatric indications has increased our understanding of other disorders and the potential for intervention in the cingulate cortex.17 In 1987, Ballantine et al. reported on a selection of 198 psychiatric patients treated with cingulotomy between 1962 and 1982. In this report patients were diagnosed according to DSM-III criteria. Indications not previously discussed in this chapter included 14 patients with severe generalized anxiety, 14 patients with schizoaffective disorder, 11 patients with schizophrenia, 23 patients with bipolar disorder, 9 patients with personality disorder, and 3 patients with anorexia nervosa. Comparisons of response to cingulotomy and primary diagnoses were analyzed in the study. Of 14 patients with phobic or generalized anxiety without an obsessive component, 11 patients achieved marked improvement of functioning. The authors found that those with obsessive compulsive disorders did not respond as successfully as did patients with generalized anxiety or affective disorders. Four of 11 schizophrenia patients demonstrated good outcome. All three anorexia patients demonstrated long-term success, although they had a difficult postoperative course. Data on cingulotomy for these less common indications described above are still very limited and were gathered retrospectively without the benefit of modern outcome rating scales; thus, the data are difficult to evaluate.

Conclusions

Cingulotomy can be a very useful therapeutic intervention in selected patients with severe, disabling, and treatment-refractory psychiatric disease, including major affective disorders, OCD, and chronic anxiety states. Despite the rise and appeal of DBS,58,59 cingulotomy still has a role to play in the treatment of severe intractable psychiatric disease. It should only be performed by an experienced, multidisciplinary team, with experience in these disorders. Cingulotomy should be considered as one part of an entire treatment plan and must be followed by an appropriate psychiatric rehabilitation program. Many patients are greatly improved after surgery, and the complications and side effect profiles are limited. Cingulotomy remains an important therapeutic option for disabling psychiatric disease and given the public health magnitude of these disorders is probably underutilized.

Baer L., et al. Cingulotomy for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder. Prospective long-term follow-up of 18 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(5):384-392.

Ballantine H., Giriunas I. Treatment of intractable psychiatric illness and chronic pain by stereotactic cingulotomy. In: Schmidek H., Sweet W. Operative Neurosurgical Techniqueseds. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1982:1069-1075.

Ballantine H.T.Jr., et al. Treatment of psychiatric illness by stereotactic cingulotomy. Biol Psychiatry. 1987;22(7):807-819.

Baxter L.R.Jr., et al. Caudate glucose metabolic rate changes with both drug and behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(9):681-689.

Corkin S., Twitchell T., Sullivan E. Safety and efficacy of cingulotomy for pain and psychiatric disorders. In: Hitchcock E., Ballantine H., Myerson B. Modern Concepts in Psychiatric Surgery. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1979:253-272.

Dougherty D.D., et al. Cerebral metabolic correlates as potential predictors of response to anterior cingulotomy for treatment of major depression. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(6):1010-1017.

Freeman W.J., Watts J.W., Hunt T. Psychosurgery: intelligence, emotion and social behavior following prefrontal lobotomy for mental disorders. Springfield, IL, and Baltimore: Charles C Thomas; 1942.

Fulton J.F. Frontal Lobotomy and Affective Behavior: a neurophysiological analysis. New York: Norton; 1951.

Goodman W.K., et al. Deep brain stimulation for intractable obsessive compulsive disorder: pilot study using a blinded, staggered-onset design. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):535-542.

Jenike M.A., et al. Cingulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. A long-term follow-up of 33 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(6):548-555.

Kelley D. Anxiety and Emotions: physiological basis and treatment. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1980.

Kelly D., Richardson A., Mitchell-Heggs N. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy: neurophysiological aspects and operative technique. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123(573):133-140.

Knight G. The orbital cortex as an objective in the surgical treatment of mental illness. The results of 450 cases of open operation and the development of the stereotactic approach. Br J Surg. 1964;51:114-124.

Kullberg G. Differences in effect of capsulotomy and cingulotomy. In: Sweet W., Obrador S., Martin-Rodriguez J. Neurosurgical Treatment in Psychiatry, Pain and Epilepsy. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1977:301-308.

Maclean P.D. Some psychiatric implications of physiological studies on frontotemporal portion of limbic system (visceral brain). Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1952;4(4):407-418.

Mayberg H.S., et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

Modell J.G., et al. Neurophysiologic dysfunction in basal ganglia/limbic striatal and thalamocortical circuits as a pathogenetic mechanism of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1989;1(1):27-36.

Moniz E. Prefrontal leucotomy in the treatment of mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1937;93:1379-1385.

Papez J. A proposed mechanism of emotion. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1937;38:725-743.

Rauch S.L., Jenike M.A. Neurobiological models of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychosomatics. 1993;34(1):20-32.

Rauch S.L., et al. Regional cerebral blood flow measured during symptom provocation in obsessive-compulsive disorder using oxygen 15-labeled carbon dioxide and positron emission tomography. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):62-70.

Shields D.C., et al. Prospective assessment of stereotactic ablative surgery for intractable major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(6):449-454.

Spangler W.J., et al. Magnetic resonance image-guided stereotactic cingulotomy for intractable psychiatric disease. Neurosurgery. 1996;38(6):1071-1076. discussion 1076–1078

Talairach J., et al. The cingulate gyrus and human behaviour. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1973;34(1):45-52.

Vogt B.A., et al. Human cingulate cortex: surface features, flat maps, and cytoarchitecture. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359(3):490-506.

1. Skvarilova B., et al. Trephinations—old surgical intervention. Acta Chir Plast. 2007;49(4):103-108.

2. Alt K.W., et al. Evidence for stone age cranial surgery. Nature. 1997;387(6631):360.

3. Dimopoulos V.G., Kapsalakis I.Z., Fountas K.N. Skull morphology and its neurosurgical implications in the Hippocratic era. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(1):E10.

4. Jordanov J., Dimitrova B., Nikolov S. Symbolic trepanations of skulls from the Middle Ages (IXth-Xth century) in Bulgaria. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988;92(1-4):15-18.

5. Lillie M.C. Cranial surgery dates back to Mesolithic. Nature. 1998;391(6670):854.

6. Piek J., et al. Stone age skull surgery in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: a systematic study. Neurosurgery. 1999;45(1):147-151. discussion 151

7. Brotis A.G., et al. Historic evolution of open cingulectomy and stereotactic cingulotomy in the management of medically intractable psychiatric disorders, pain and drug addiction. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2009;87(5):271-291.

8. Moniz E. Prefrontal leucotomy in the treatment of mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1937;93:1379-1385.

9. Freeman W.J., Watts J.W., Hunt T. Psychosurgery: intelligence, Emotion and social behavior following prefrontal lobotomy for mental disorders. Springfield, IL and Baltimore: C.C. Thomas; 1942.

10. Tooth J., Newton M. Leucotomy in England and Wales 1942–1954: reports on public health and medical subjects. No. 104. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1961.

11. Horwitz N.H. Library: historical perspective. John Farquhar Fulton. Neurosurgery. 1998;43(1):178-184.

12. Fulton J.F. Frontal Lobotomy And Affective Behavior: a neurophysiological analysis. New York: Norton; 1951.

13. Le Beau J. Anterior cingulectomy in man. J Neurosurg. 1954;11(3):268-276.

14. Whitty C.W., et al. Anterior cingulectomy in the treatment of mental disease. Lancet. 1952;1(6706):475-481.

15. Whitty C.W. Effects of anterior cingulectomy in man. Proc R Soc Med. 1955;48(6):463-469.

16. Foltz E.L., White L.E.Jr. Pain “relief” by frontal cingulumotomy. J Neurosurg. 1962;19:89-100.

17. Ballantine H.T.Jr., et al. Treatment of psychiatric illness by stereotactic cingulotomy. Biol Psychiatry. 1987;22(7):807-819.

18. Knight G. The orbital cortex as an objective in the surgical treatment of mental illness. The results of 450 cases of open operation and the development of the stereotactic approach. Br J Surg. 1964;51:114-124.

19. Kelly D., Richardson A., Mitchell-Heggs N. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy: neurophysiological aspects and operative technique. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123(573):133-140.

20. Nimchinsky E.A., et al. Spindle neurons of the human anterior cingulate cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1995;355(1):27-37.

21. Vogt B.A., et al. Human cingulate cortex: surface features, flat maps, and cytoarchitecture. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359(3):490-506.

22. Afifi A.K., Bergman R.A. Functional Neuroanatomy: text and atlas. International ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Division; 1998.

23. Papez J. A proposed mechanism of emotion. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1937;38:725-743.

24. Maclean P.D. Some psychiatric implications of physiological studies on frontotemporal portion of limbic system (visceral brain). Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1952;4(4):407-418.

25. Ranson S.W. Some Functions of the Hypothalamus: harvey lecture, december 17, 1936. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1937;13(5):241-271.

26. Mesulam M. Patterns in behavioral neuroanatomy: association areas, the limbic system, and hemispheric specialization. In: Mesulam M., editor. Principles of Behavioral Neurology. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1985:1-70.

27. Kelley D. Anxiety and Emotions: physiological basis and treatment. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1980.

28. Laitinen L.V. Emotional responses to subcortical electrical stimulation in psychiatric patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1979;81(3):148-157.

29. Talairach J., et al. The cingulate gyrus and human behaviour. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1973;34(1):45-52.

30. Baxter L.R.Jr., et al. Caudate glucose metabolic rate changes with both drug and behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(9):681-689.

31. Rauch S.L., Jenike M.A. Neurobiological models of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychosomatics. 1993;34(1):20-32.

32. Rauch S.L., et al. Regional cerebral blood flow measured during symptom provocation in obsessive-compulsive disorder using oxygen 15-labeled carbon dioxide and positron emission tomography. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):62-70.

33. Baxter L.R.Jr., et al. Reduction of prefrontal cortex glucose metabolism common to three types of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(3):243-250.

34. Modell J.G., et al. Neurophysiologic dysfunction in basal ganglia/limbic striatal and thalamocortical circuits as a pathogenetic mechanism of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1989;1(1):27-36.

35. Gorman J.M., et al. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revised. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):493-505.

36. Gorman J.M., et al. A neuroanatomical hypothesis for panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(2):148-161.

37. Spangler W.J., et al. Magnetic resonance image-guided stereotactic cingulotomy for intractable psychiatric disease. Neurosurgery. 1996;38(6):1071-1076. discussion 1076–1078

38. Jenike M.A., et al. Cingulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. A long-term follow-up of 33 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(6):548-555.

39. Baer L., et al. Cingulotomy for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder. Prospective long-term follow-up of 18 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(5):384-392.

40. Ballantine H., Giriunas I. Treatment of intractable psychiatric illness and chronic pain by stereotactic cingulotomy. In: Schmidek H., Sweet W. Operative Neurosurgical Techniqueseds. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1982:1069-1075.

41. Corkin S., Twitchell T., Sullivan E. Safety and efficacy of cingulotomy for pain and psychiatric disorders. In: Hitchcock E., Ballantine H., Myerson B. Modern Concepts in Psychiatric Surgery. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1979:253-272.

42. Pippard J. Rostral leucotomy: a report on 240 cases personally followed up after 1 1/2 to 5 years. J Ment Sci. 1955;101(425):756-773.

43. Kullberg G. Differences in effect of capsulotomy and cingulotomy. In: Sweet W., Obrador S., Martin-Rodriguez J. Neurosurgical Treatment in Psychiatry, Pain and Epilepsy. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1977:301-308.

44. Fodstad H., et al. Treatment of chronic obsessive compulsive states with stereotactic anterior capsulotomy or cingulotomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1982;62(1-2):1-23.

45. Mindus P., Rasmussen S.A., Lindquist C. Neurosurgical treatment for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: implications for understanding frontal lobe function. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6(4):467-477.

46. Mindus P., Nyman H. Normalization of personality characteristics in patients with incapacitating anxiety disorders after capsulotomy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;83(4):283-291.

47. Le Moal M., Koob G.F. Drug addiction: pathways to the disease and pathophysiological perspectives. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17(6-7):377-393.

48. Kalivas P.W., Volkow N.D. The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(8):1403-1413.

49. Stelten B.M., et al. The neurosurgical treatment of addiction. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25(1):E5.

50. Lubman D.I., Yucel M., Pantelis C. Addiction, a condition of compulsive behaviour? Neuroimaging and neuropsychological evidence of inhibitory dysregulation. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1491-1502.

51. Balasubramaniam V., Kanaka T.S., Ramanujam P.B. Stereotaxic cingulumotomy for drug addiction. Neurol India. 1973;21(2):63-66.

52. Kanaka T.S., Balasubramaniam V. Stereotactic cingulumotomy for drug addiction. Appl Neurophysiol. 1978;41(1-4):86-92.

53. Mitchell-Heggs N., Kelly D., Richardson A. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy—a follow-up at 16 months. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;128:226-240.

54. Shields D.C., et al. Prospective assessment of stereotactic ablative surgery for intractable major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(6):449-454.

55. Kim M.C., Lee T.K., Choi C.R. Review of long-term results of stereotactic psychosurgery. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002;42(9):365-371.

56. Pokorny A.D. Prediction of suicide in psychiatric patients. Report of a prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(3):249-257.

57. Dougherty D.D., et al. Cerebral metabolic correlates as potential predictors of response to anterior cingulotomy for treatment of major depression. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(6):1010-1017.

58. Mayberg H.S., et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651-660.

59. Goodman WK, et al. Deep brain stimulation for intractable obsessive compulsive disorder: pilot study using a blinded, staggered-onset design. Biol Psychiatry. 67(6):535–542.