Chapter 16

Chronic Stable Angina

1. Can a patient with new-onset chest pain have chronic stable angina?

2. What causes chronic stable angina?

3. How is chronic stable angina classified or graded?

The most commonly used system is the Canadian Cardiovascular Society system, in which angina is graded on a scale of I to IV. These grades and this system are described in Table 16-1. This grading system is useful for evaluating functional limitation, treatment efficacy, and stability of symptoms over time.

TABLE 16-1

GRADING OF ANGINA BY THE CANADIAN CARDIOVASCULAR SOCIETY CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

Class I

Class II

Angina occurs while walking or climbing stairs rapidly; while walking uphill; while walking or climbing stairs after meals in cold or in wind; while under emotional stress; or only during the first several hours after waking.

Angina occurs while walking or climbing stairs rapidly; while walking uphill; while walking or climbing stairs after meals in cold or in wind; while under emotional stress; or only during the first several hours after waking.

Angina occurs while walking > 2 blocks on level grade and climbing > 1 flight of ordinary stairs at a normal pace and in normal conditions.

Angina occurs while walking > 2 blocks on level grade and climbing > 1 flight of ordinary stairs at a normal pace and in normal conditions.

Class III

Angina occurs while walking 1 or 2 blocks on level grade and climbing 1 flight of stairs in normal conditions and at a normal pace

Angina occurs while walking 1 or 2 blocks on level grade and climbing 1 flight of stairs in normal conditions and at a normal pace

Class IV

4. What tests should be obtained in the patient with newly diagnosed angina?

5. What are the goals of treatment in the patient with chronic stable angina?

Prevent major cardiovascular (CV) events, such as heart attack or cardiac death

Prevent major cardiovascular (CV) events, such as heart attack or cardiac death

Identify “high risk” patients who would benefit from revascularization

Identify “high risk” patients who would benefit from revascularization

6. What therapies improve symptoms?

7. What is the initial approach to the patient with chronic stable angina?

The initial approach should be focused on eliminating unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and effectively promoting lifestyle changes that reduce CV risk, such as maintaining a healthy weight, engaging in physical activity, and adopting a healthy diet. In addition, annual influenza vaccination reduces mortality (by approximately 35%) and morbidity in patients with underlying CAD. Tight glycemic control was thought to be important in the diabetic, but this approach actually increases the risk of CV death and complications.

8. What is first-line drug therapy for the treatment of stable angina?

9. Is any β-blocker better than the others?

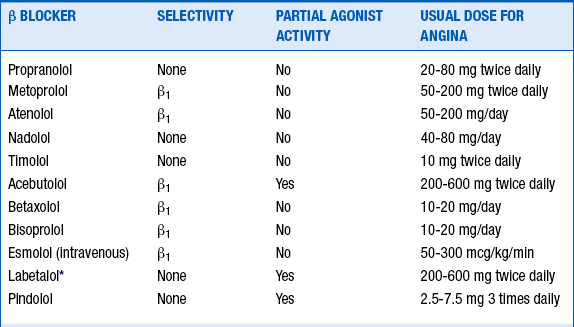

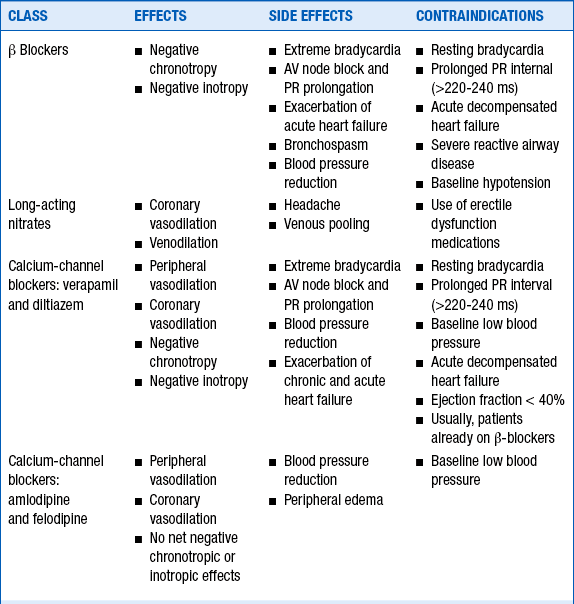

Although the various β-blockers have different properties (i.e., cardioselectivity, vasodilating actions, concomitant α-adrenergic inhibition, and partial β-agonist activity [Table 16-2]), they appear to have similar efficacy in patients with chronic stable angina. β-blockers prevent reinfarction and improve survival in survivors of MI, but such benefits have not been demonstrated in patients with chronic CAD without previous MI.

10. What is the proper dose of β-blocker?

11. Calcium channel blocker versus β-blocker: is one more effective than the other?

Calcium channel blockers and β-blockers are similarly effective at relieving angina and improving exercise time to the onset of angina or ischemia. Calcium channel blockers can be used as monotherapy in patients with chronic stable angina, although combination therapy with a β-blocker or nitrate relieves angina more effectively than does their use alone. In this regard, β-blockers may be particularly useful in blunting the reflex tachycardia that occurs with dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker use.

12. When should a peripherally acting calcium channel blocker (i.e., a dihydropyridine, such as amlodipine or felodipine) be used versus one that has effects on both the heart and the periphery (e.g., verapamil, diltiazem)?

13. Should sublingual nitroglycerin (NTG) or NTG spray be prescribed to all chronic stable angina patients?

14. When is a long-acting nitrate prescribed?

Long-acting nitrates are often prescribed along with β-blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (i.e., verapamil or diltiazem) as the initial treatments in patients with chronic stable angina (Table 16-3). Continuous exposure to NTG can result in tolerance to its vasodilating effects. Nitrate tolerance can be avoided by providing the patient with a “nitrate-free” period for 4 to 6 hours per day.

It’s use is reserved for individuals with angina that is refractory to maximal doses of other antianginal medications. Ranolazine targets the underlying derangements in sodium and calcium that occur during myocardial ischemia; it does not affect resting heart rate or blood pressure. Its antianginal efficacy is not related to its effect on heart rate, the hemodynamic state, the inotropic state, or coronary blood flow, as with other currently available agents.

16. What medications prevent MI or death in patients with stable chronic angina?

17. What’s the proper dose of aspirin?

An aspirin dose of 75 to 162 mg daily is equally as effective as 325 mg, but with a lower risk of bleeding. Doses less than 75 mg have less proven benefit. In patients with chronic CAD, aspirin treatment is associated with a 33% reduction in the risk of vascular events (nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and vascular death). Over the course of a couple of years of treatment, aspirin would be expected to prevent about 10 to 15 vascular events for every 1000 people treated.

18. Should patients with chronic stable angina be on clopidogrel?

19. Should patients with chronic stable angina be treated with an ACE inhibitor?

20. What’s the proper statin dose for the patients with chronic stable angina?

21. Which patients with chronic stable angina should be referred for stress testing?

The chronic stable angina guidelines advocate obtaining a stress test for prognostic reasons in many cases—if the stress test reveals low-risk findings, then the patient can be managed medically, whereas if the stress test reveals high-risk findings, the patient is usually referred for cardiac catheterization.

22. Which patients with chronic stable angina should have a cardiac catheterization?

High risk findings on stress testing

High risk findings on stress testing

Symptoms not adequately controlled with antianginal medications

Symptoms not adequately controlled with antianginal medications

23. Which patients with chronic stable angina should be referred for revascularization?

3 vessel CAD and depressed ejection fraction (less than 50%)

3 vessel CAD and depressed ejection fraction (less than 50%)

Multivessel CAD with stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery.

Multivessel CAD with stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery.

24. Is there an easy way to remember how to manage the patient with chronic stable angina?

The “ABCDEs” of treatment for patients with chronic stable angina

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012;126:3097–3137. Available at: http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/126/25/3097.full.pdf+html. Accessed Feb 9, 2013.

2. Bhatt, D.L., Fox, K.A., Hacke, W., et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1706–1717.

3. Boden, W.E., O’Rourke, R.A., Teo, K.K., et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503–1516.

4. Braunwald, E., Domanski, M.J., Fowler, S.E., et al. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition in stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2058–2068.

5. Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86.

6. Fox, K.M. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study). Lancet. 2003;362:782–788.

7. Gerstein, H.C., Miller, M.E., Genuth, S., et al. Long-term effects of intensive glucose lowering on cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:818–828.

8. Hillis, L.D., Smith, P.K., Anderson, J.L., et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Executive Summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2584–2614.

9. Levine, G.N., Bates, E.R., Blankenship, J.C., et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for percutaneous intervention: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2550–2583.

10. Serruys, P.W., Morice, M.C., Kappetein, A.P., et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–972.

11. Trikalinos, T.A., Alsheikh-Ali, A.A., Tatsioni, A., Nallamothu, B.K., Kent, D.M. Percutaneous coronary interventions for non-acute coronary artery disease: a quantitative 20-year synopsis and a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:911–918.

12. Weintraub, W.S., Spertus, J.A., Kolm, P., et al. Effect of PCI on quality of life in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:677–687.