Chapter 412 Chronic Severe Respiratory Insufficiency

412.1 Neuromuscular Diseases

Neuromuscular diseases (NMDs) of childhood include muscular dystrophies, metabolic and congenital myopathies, anterior horn cell disorders, peripheral neuropathies, and diseases that affect the neuromuscular junction. Decreases in muscle strength and endurance resulting from neuromuscular disorders can affect any skeletal muscle, including muscles involved in respiratory function. Of particular concern are those muscles mediating upper airway patency, generation of cough, and lung inflation. Acute respiratory insufficiency is often the most prominent clinical manifestation of several acute neuromuscular disorders, such as high-level spinal cord injury, poliomyelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome (Chapter 608), and botulism (Chapter 202). Although much more insidious in its clinical course, respiratory dysfunction constitutes the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in progressive neuromuscular disorders (e.g., Duchenne muscular dystrophy [Chapter 601], spinal muscular atrophy, congenital myotonic dystrophy, myasthenia gravis [Chapter 604], and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease [Chapter 605]).

Treatment

Even though gene-targeted therapies are being developed for some NMDs, current interventions are primarily supportive rather than curative. Close surveillance through periodic review of the history and physical examination is critical. The development of personality changes, such as irritability, decreased attention span, fatigue, and somnolence, may point to the presence of sleep-associated gas exchange abnormalities and sleep fragmentation. Changes in speech and voice characteristics, nasal flaring, and the use of other accessory muscles during quiet breathing at rest may provide sensitive indicators of progressive muscle dysfunction and respiratory compromise. Although the frequency of periodic re-evaluation needs to be tailored to the individual patient, tentative guidelines were developed for patients with DMD; an abbreviated summary of such recommendations, applicable to all children with NMDs, is provided in Table 412-1.

Table 412-1 PROPOSED GUIDELINES FOR INITIAL EVALUATION AND FOLLOW-UP OF PATIENTS WITH NEUROMUSCULAR DISEASE

| INITIAL EVALUATION | BASIC INTERVENTION/TRAINING |

|---|---|

| History/physical/anthropometrics | Nutritional consultation and guidance |

| Lung function and maximal respiratory pressures (PFTs) | Regular chest physiotherapy |

| Arterial blood gases | Use of percussive devices |

| Polysomnography* | Respiratory muscle training |

| Exercise testing (in selected cases) | Annual influenza vaccine |

| If vital capacity >60% predicted or maximal respiratory pressures >60 cm H2O | Evaluate PFTs every 6 mo |

| CXR and polysomnography every year | |

| If vital capacity <60% predicted or maximal respiratory pressures <60 cm H2O | Evaluate PFTs every 3-4 mo |

| CXR, MIP/MEP every 6 mo | |

| Polysomnography every 6 mo to every year |

CXR, chest x-ray; MEP, maximal expiratory pressure; MIP, maximal inspiratory pressure; PFT, pulmonary function test.

* Please note that if polysomnography is not readily available, multichannel recordings including oronasal airflow, nocturnal oximetry, and end-tidal carbon dioxide levels may provide an adequate alternative.

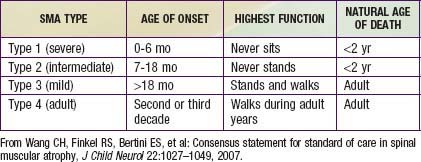

Guidelines for evaluation and management of patients with SMA were developed on the basis of expert consensus. Four classifications of SMA, based on age of onset and level of function, are recognized (Table 412-2). Treatment of SMA is focused on level of function (non-sitter, sitter, or walker) rather than SMA type. Unlike patients with DMD, patients with SMA do not demonstrate correlation between pulmonary function and need for mechanical ventilatory support. Rather, longitudinal monitoring for signs and symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing and ineffective airway clearance should be utilized to direct patient care.

Annane D, Orlikowski D, Chevret S, et al. Nocturnal mechanical ventilation for chronic hypoventilation in patients with neuromuscular and chest wall disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:1-34.

Kennedy JD, Martin AJ. Chronic respiratory failure and neuromuscular disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:261-273.

Simonds AK. Recent advances in respiratory care for neuromuscular disease. Chest. 2006;130:1879-1886.

Wang CH, Finkel RS, Bertini ES, et al. Consensus statement for standard of care in spinal muscular atrophy. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:1027-1049.

412.2 Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome

Genetics

The majority of CCHS cases occur because of a de novo PHOX2B mutation, but 5-10% of children with CCHS inherit the mutation from an asymptomatic parent who is mosaic for the PHOX2B mutation. CCHS is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Therefore, an individual with CCHS has a 50% chance of transmitting the mutation, and resulting disease phenotype, to each child. Mosaic parents have up to a 50% chance of transmitting the PHOX2B mutation to each offspring. Genetic counseling is essential for family planning and for preparedness in the delivery room for an anticipated CCHS birth. PHOX2B testing is advised for both parents of a child with CCHS to anticipate risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies. Further, prenatal testing for PHOX2B mutation is clinically available (www.genetests.org) for families with a known PHOX2B mutation.

Differential Diagnosis

Bougneres P, Pantalone L, Linglart A, et al. Endocrine manifestations of the rapid-onset obesity with hypoventilation, hypothalamic, autonomic dysregulation, and neural tumor syndrome in early childhood. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;93:3971-3980.

Carroll MS, Pallavi PP, Weese-Mayer DE. Carbon dioxide chemoreception and hypoventilation syndromes with autonomic dysregulation. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:979-988.

Gronli JO, Santucci BA, Leurgans SE, et al. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome: PHOX2B genotype determines risk for sudden death. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43:77-86.

Ize-Ludlow D, Gray J, Sperling MA, et al. Rapid onset obesity with hypothalamic dysfunction, hypoventilation, and autonomic dysregulation presenting in childhood. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e179-e188.

Katz ES, McGrath S, Marcus CL. Late-onset central hypoventilation with hypothalamic dysfunction: a distinct clinical syndrome. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;29:62-68.

Kinney HC. Structural abnormalities in the brainstem and cerebellum in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:226-227.

Kumar R, Lee K, Macey P, et al. Mammillary body and fornix injury in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:429-434.

Kumar R, Macey PM, Woo MA, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging demonstrates brainstem and cerebellar abnormalities in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:275-280.

Marazita ML, Maher BS, Cooper ME, et al. Genetic segregation analysis of autonomic nervous system dysfunction in families of probands with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2001;100:229-236.

Patwari PP, Carroll MS, Rand CM, et al. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome and the PHOX2B gene: a model of respiratory and autonomic dysregulation. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010. Jun 30 [Epub ahead of print]

Todd ES, Weinberg SM, Berry-Kravis EM, et al. Facial phenotype in children and young adults with PHOX2B-determined congenital central hypoventilation syndrome: quantitative pattern of dysmorphology. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:39-45.

Weese-Mayer DE, Berry-Kravis EM, Ceccherini I, et al. An official ATS clinical policy statement. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome: genetic basis, diagnosis, and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:626-644.

Weese-Mayer DE, Marazita ML, Berry-Kravis EM. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Pagon RA, Bird TC, Dolan CR, et al, editors. GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle, 1993. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=ondine.

Weese-Mayer DE, Rand CM, Berry-Kravis EM, et al. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome from past to future: model of translational and transitional autonomic medicine. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:521-535.

Weese-Mayer DE, Silvestri JM, Huffman AD, et al. Case/control family study of ANS dysfunction in idiopathic congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2001;100:237-245.

412.3 Other Conditions

Myelomeningocele with Arnold-Chiari Type II Malformation

Arnold-Chiari type II malformation (Chapter 585.11) is associated with myelomeningocele, hydrocephalus, and herniation of the cerebellar tonsils, caudal brainstem, and the fourth ventricle through the foramen magnum.

Rapid-Onset Obesity, Hypothalamic Dysfunction, and Autonomic Dysregulation (Chapter 412.2)

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Treatment

When adenotonsillar hypertrophy is suspected, a consultation with an ear, nose, and throat specialist for adenoid tonsillectomy may be indicated. For patients who are not candidates for this treatment or who persist with OSA, CPAP or BiPAP during sleep may alleviate the obstruction (Chapter 17).

Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)

Management

Immobilization and stabilization of the spine must be accomplished simultaneously with resuscitation and stabilization. Patients with high SCI in many instances require lifelong ventilation. Depending on the patient’s age and general condition, tracheostomy with mechanical ventilation or diaphragmatic pacing may be indicated. Often patients with diaphragmatic pacing need tracheostomy placement if there is no coordination between pacing and glottis opening. Muscle spasms occur frequently in these patients and are treated with muscle relaxants. Occasionally the muscle spasms involve the chest and present a serious impediment to ventilation. Continuous intrathecal infusion of muscle relaxant may be indicated (Chapter 598.5).

Metabolic Disease

Lung Disease

Common metabolic lung conditions include bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and recuperation from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Former premature infants recuperating from respiratory distress syndrome may experience BPD (Chapters 95.3 and 410). Volutrauma, barotrauma, and air leak syndromes incurred during mechanical ventilation contribute to lung injury. When extreme, BPD may progress to respiratory failure. Increased pulmonary vascular resistance, pulmonary hypertension, cor pulmonale, and lower airway obstruction are known complications.

Severe Tracheomalacia and/or Bronchomalacia (Airway Malacia)

Conditions associated with airway malacia include tracheoesophageal fistula, innominate artery compression, and pulmonary artery sling after surgical repair (Chapter 381). Patients with tracheobronchomalacia present with cough, lower airway obstruction, and wheezing. Diagnosis is made via bronchoscopy, preferably with the patient breathing spontaneously. Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) titration during the bronchoscopy helps identify the airway pressure required to maintain airway patency and prevent tracheobronchial collapse.

Bembi B, Cerini E, Danesino C, et al. Management and treatment of glycogenosis type II. Neurology. 2008;71:S12-S36.

Davin Miller J, Waldemar AC. Pulmonary complications of mechanical ventilation in neonates. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:273-281.

Dayyat E, Kheeirandish-Gozal L, Gozal D. Childhood obstructive sleep apnea: one or two distinct disease entities? Sleep Med Clin. 2007;2:433-444.

Lee JH, Sung IY, Kang JY, et al. Characteristics of pediatric onset spinal cord injury. Pediatr Int. 2009;51:254-257.

Muzumdar H, Arens R. Central alveolar hypoventilation syndromes. Sleep Med Clin. 2008;3:601-615.

Young AH, Cowan MJ, Horn B, et al. Airway management in children with mucopolysaccharidoses. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:73-79.

412.4 Long-Term Mechanical Ventilation

The prognosis of the disease is a critical factor in the decision to initiate long-term ventilation. The discharge process for a child undergoing ventilatory support should start as soon as the child is medically stable and supported by equipment that can be maintained in the home. Children with degenerative neuromuscular disease, such as type I SMA, suffer from respiratory failure very early in life, often triggered by the first respiratory illness. Although some parents decide to provide only palliative end-of-life care (Chapter 40) for the child with SMA, others choose long-term invasive or noninvasive ventilatory support. Young children with chronic lung disease and airway malacia have the potential to improve their pulmonary function and to wean successfully off ventilator support if provided with adequate ventilation, good nutrition, and measures to promote development and prevent further lung injury.

Respiratory Equipment for Home Care

Modes of mechanical ventilation support are discussed in Chapter 65.1.

Diaphragmatic Pacing

Detailed in the management section of Ch. 412.2, diaphragm pacers may also be considered in children with spinal cord injury involving a level above C3, though the immediate advantages are less apparent than in CCHS.

Infections

Infections—tracheitis (Chapter 377.2), bronchitis (Chapter 383.2), pneumonia (Chapter 392)—are common in patients with chronic respiratory failure. They may be due to community-acquired viruses (adenovirus, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza) or community- or hospital-acquired bacteria. Many of the latter organisms are gram-negative, highly antimicrobial-resistant pathogens that cause further deterioration in pulmonary function. Bacterial infection is most likely in the presence of fever, deteriorating lung function (hypoxia, hypercarbia, tachypnea, retractions), leukocytosis, and mucopurulent sputum. The presence of leukocytes and organisms on Gram stain of tracheal aspirate, as well as the visualization of new infiltrates on radiographs, may be consistent with bacterial infection. Infection must be distinguished from tracheal colonization, which is asymptomatic and associated with normal amounts of clear tracheal secretions. If infection is suspected, it must be treated with antibiotics, based on the culture and sensitivities of organisms recovered from the tracheal aspirate. Inhaled tobramycin, started early, may avert more serious infection. Infections should be prevented by appropriate immunizations (influenza, pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae type b), passive immunity (respiratory syncytial virus), and good tracheostomy care. Antibiotics should be used judiciously to prevent further colonization with drug-resistant organisms. However, some patients who have recurrent infections may benefit from prophylaxis with inhaled antibiotics.

Fischer JR. Home ventilator guide. International Ventilator Users Network, affiliate of Post-Polio Health International, St Louis, 2008. www.post-polio.org/ivun/index.html.

Graham RJ, Fleegler EW, Robinson WM. Chronic ventilator need in the community: a 2005 pediatric census of Massachusetts. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1280-1287.

O’Brien JE, Dumas HM, Haley SM, et al. Ventilator weaning outcomes in chronic respiratory failure in children. Int J Rehab Res. 2007;30:171-174.

Siner JM, Manthous CA. Liberation from mechanical ventilation: what monitoring matters? Crit Care Clin. 2007;23:613-638.