CHAPTER 61 Chronic pelvic pain

Biology of Pain

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’ (IASP Task Force on Taxonomy 1994). The emphasis in this definition is that pain is an experience rather than a neurophysiological process, and is therefore subjective. There is no such thing as ‘objective’ pain. This does not mean, however, that pain cannot be studied or that reproducible experimental models cannot be devised. Neuroscience has advanced knowledge of the biological processes underlying pain. It is no longer appropriate to discuss the subject in terms of ‘pain pathways’, by analogy with a wiring diagram, or even to consider that the nervous system conveys perceptions such as touch or pain. Rather, the elements of the nervous system, comprising the ‘different fibres, tracts, pathways and nuclei process and convey information about bodily stimulus events’ (Berkley and Hubscher 1995). In this model, pain is a central nervous system construct derived from the totality of sensory input rather than from the activation of a particular pathway. Even the anatomy of neural pathways in the adult cannot be considered immutable; plasticity of the central nervous system has been clearly demonstrated in reproducible animal experimental models, such that a nerve injury leads to sprouting of afferent fibres within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Woolf et al 1992).

Special features of chronic and visceral pain

The processes underlying the transition from a single or repeated acute painful episode to a chronic pain state are of great potential clinical significance. Patients often relate the onset of their chronic condition to an event such as an acute infection or surgical procedure. Moreover, visceral sensory mechanisms differ in certain respects from those found in cutaneous tissues. Key mechanisms potentially underlying the transition from acute to chronic visceral pain states are the activation of silent afferents in viscera (McMahon 1997) and central sensitization (Woolf 1983). There are certain similarities but also important differences in the context of visceral sensation between central sensitization and wind-up, where the response to repeated C-fibre stimulation is progressively augmented (Herrero et al 2000). It had been hoped that the development of central sensitization and/or wind-up could be modulated by analgesics or other agents using a therapeutic strategy of pre-emptive analgesia (Dickenson 1997), although clinical applications of this concept have been disappointing.

Vascular pain and pelvic congestion

By analogy with the pathogenesis of cerebral migraine, it has been suggested that pain associated with pelvic congestion might arise through vascular perturbation at the ovarian or uterine arteriolar level, resulting in the release of endothelial factors such as ATP which act by exciting sensory nerves in the outer muscle coat of venules and veins, and which also cause vasodilatation through the release of nitric oxide (Stones 2000).

Sex differences in pain

There is a marked sex difference in the prevalence of a number of chronic painful conditions unrelated to the reproductive tract in the general population, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), temporomandibular dysfunction and interstitial cystitis, which has prompted research on the potential underlying mechanisms using animal models such as bladder irritation (Bon et al 1997), and uterine and vaginal distension (Bradshaw et al 1999). Illustrating the complexity of the central mechanisms underlying nociception, vaginal hyperalgesia resulting from induced endometriosis in rats was exacerbated in the presence of increased oestradiol levels, whereas in ovariectomized animals, hyperalgesia was relieved by oestradiol (Berkley et al 2007).

Studies of human volunteers have investigated pain thresholds in women at different stages of the menstrual cycle using electrical stimulation, pressure dolorimetry on the skin, thermal stimulation and induced ischaemic pain. Patterns of variation in response seen in studies using these modalities were different, and a meta-analytical review of pain perception across the menstrual cycle (Riley et al 1999) estimated the effect size for menstrual cycle fluctuation of pain sensitivity between the most and least sensitive phase to be 0.40. The effect size for sex difference was approximately 0.55, indicating that hormone variability could account for a substantial proportion but not all of the observed differences.

Illustrating some of the possible underlying mechanisms, a study of the discrimination of thermal pain in male and female volunteers showed that women had a lower pain threshold and tolerance, as also noted in a number of other studies (Fillingim et al 1998). A further complexity to be considered when interpreting studies of human volunteers is that subjects may well have prior pain experience which could influence responses to experimental pain (Fillingim et al 1999). Finally, the potential influence on pain perception of exogenous hormone therapy needs to be considered. In 87 postmenopausal women consulting for chronic orofacial pain, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was associated with greater reported levels of pain, with substantial effect sizes between 0.39 and 0.62 (Wise et al 2000). The possibility of increased pain as a result of HRT use has not been addressed prospectively but may be clinically important, especially in women with vulval pain where oestrogen deficiency changes are thought to coexist.

Genetic variation in susceptibility to pain

There is now evidence for a genetic basis for the variation in response to pain seen in human experimental studies. Shabalina et al (2009) studied polymorphisms of the ‘mu’ opioid receptor OPRM1 gene locus, and reported a strong association between the single nucleotide polymorphism rs563649 and individual variations in pain perception. There are also relevant observations from clinical populations with gynaecological pain; for example, a twin study showed that while 39% of the variance in reported menstrual flow was accounted for by genetic factors, the corresponding figure for dysmenorrhoea was 55% and for functional limitation from menstrual symptoms was 77% (Treloar et al 1998).

Epidemiology of Pelvic Pain: Populations, Consulting and Referral Patterns

The first assessment of the prevalence and economic burden associated with chronic pelvic pain was based on extrapolation from hospital practice in the UK, and estimated the prevalence in women at 24.4 per 1000. The annual direct treatment cost was estimated at £158 million, with indirect costs of £24 million (Davies et al 1992). The above prevalence now appears an underestimate since data from population-based studies have become available. A telephone survey was undertaken in the USA using a robust sampling methodology (Mathias et al 1996). Women aged 18–50 years were interviewed about pelvic-pain-related symptoms. In total, 17,927 households were contacted, 5325 women agreed to participate and 925 reported pelvic pain of at least 6 months’ duration, including pain within the past 3 months. Following exclusion of pregnant and postmenopausal women and those with pain that was solely cycle related, 773/5263 (14.7%) were identified as suffering from chronic pelvic pain. Direct costs of health care, estimated from Medicare tariffs and hence very conservative, were $881.5 million, patients’ out-of-pocket expenses were estimated at $1.9 billion and indirect costs due to time off work were estimated at $555.3 million.

In the UK, the population perspective was provided by a postal survey of 2016 women selected at random from the Oxfordshire Health Authority register of 141,400 women aged 18–49 years (Zondervan et al 2001b). Chronic pelvic pain was defined as recurrent pain of at least 6 months’ duration, unrelated to periods, intercourse or pregnancy. For the survey, a ‘case’ was defined as a women with chronic pelvic pain in the previous 3 months, and on this basis the prevalence was 483/2016 (24.0%). Among those with pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea was reported by 81% of those who had periods, and dyspareunia was reported by 41% of those who were sexually active. Among women who did not have chronic pelvic pain as defined above, dysmenorrhoea was reported by 58% of those who had periods, and dyspareunia was reported by 14% of those who were sexually active.

An estimate of the consulting pattern associated with pelvic pain was obtained using a national database study of UK general practices (Zondervan et al 1999b). Data relating to 284,162 women aged 12–70 years who had a general practice contact in 1991 were analysed to identify subsequent contacts over the following 5 years. The monthly prevalence rate was 21.5/1000 and the monthly incidence rate was 1.58/1000. These prevalence rates are comparable with those for migraine, back pain and asthma in primary care. Older women had higher monthly prevalence rates; for example, the rate was 18.2/1000 in women aged 15–20 years and 27.6/1000 in women over 60 years of age. This association is thought to be due to persistence of symptoms in older women, with the median duration of symptoms being 13.7 months in 13–20 year olds and 20.2 months in women over 60 years of age (Zondervan et al 1999a). It is clear that future population-based studies need to include older women.

Among 483 women with chronic pelvic pain participating in the Oxfordshire population study discussed above, 195 (40.4%) had not sought a medical consultation, 127 (26.3%) reported a past consultation and 139 (28.8%) reported a recent consultation for pain (Zondervan et al 2001b). Of those women identified as cases of pelvic pain in the national general practice database, 28% were not given a specific diagnosis and 60% were not referred to hospital (Zondervan et al 1999a). The US population-based study discussed above also drew attention to the large numbers of women who have troublesome symptoms but do not seek medical attention: 75% of this sample had not seen a healthcare provider in the previous 3 months. It might be thought that not seeking care would be an indicator of milder symptoms; indeed, in the US study, those who did seek medical attention had higher pain and lower general health scores than those who did not seek medical attention. However, among those not seeking help, scores for pain and functional impairment were still substantial. Lack of use of medical services might reflect sociocultural factors, but could equally reflect previous unsatisfactory experiences of investigation and treatment, as discussed later in this chapter.

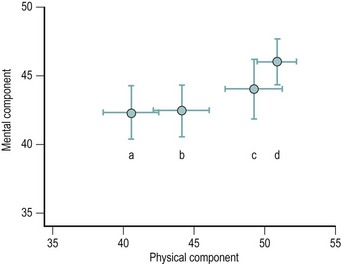

Among women referred to a UK gynaecology outpatient clinic with chronic pelvic pain of at least 6 months’ duration, the impact of the condition on quality of life was assessed using the Short Form-36 (SF-36) questionnaire (Stones et al 2000). Figure 61.1 shows a comparison of physical and mental component summary scores derived from the eight SF-36 subscales (Jenkinson et al 1996a) in this hospital population with the data from the Oxfordshire population study described above. These summary scores are adjusted such that 50 represents a normal population mean. It will be noted that, as might be expected, the hospital sample is consistent with the trend, evident in those who have previously or recently sought medical advice compared with those who have not, to greater impairment of function on both physical and mental components.

Figure 61.1 Means ± 95% confidence interval for the Short Form-36 mental component and physical component summary scales. Women with pelvic pain (a) seen in a general gynaecology clinic (Stones et al 2000), or in a postal survey (Zondervan et al 2001b) reporting (b) a recent consultation, (c) a previous consultation or (d) no medical consultation. Arbitrary units such that 50 represents the mean of a normal population.

From Stones RW, Selfe SA, Fransman S, Horn SA (2000) Psychosocial and economic impact of chronic pelvic pain. Baillière’s Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 14:27–43 and From Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP et al (2001b) The community prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in women and associated illness behaviour. British Journal of General Practice 51(468):541–547.

Psychological Factors in Chronic Pelvic Pain

Many writers on pelvic pain have attempted to characterize an adverse psychological profile which might help the clinician to distinguish between ‘organic’ and ‘psychogenic’ pain; a distinction not in keeping with current neurophysiological understanding as discussed above. It is likely that some of the psychological disturbance that can be identified in women with chronic pelvic pain is the result of longstanding pain symptoms and unsatisfactory treatment, rather than the cause of pain (Slocumb et al 1989). Pain may contribute to or confirm a sense of helplessness or a tendency to engage in catastrophic thoughts, and may itself be exacerbated by them (Horn and Munafo 1997). On the other hand, it is clear that concomitant mood disturbance or specific psychopathology may impair the patient’s ability to cope with her symptoms and contribute to functional impairment, and recognition is important but often neglected in the hurried setting of a gynaecology clinic (Yonkers and Chantilis 1995). The presence of adverse psychological propensities such as catastrophizing is a factor affecting outcome of treatment for chronic pelvic pain (Weijenborg et al 2008).

Depression

Women presenting with multiple pain symptoms are at especially high risk for current mood disturbance; the likelihood of an associated mood disorder was increased six-fold in individuals with two pain complaints and eight-fold in those with three complaints (Dworkin et al 1990). In keeping with the irrelevance of the organic/psychogenic distinction for diagnosis, the absence of laparoscopically visible pathology was not associated with a higher probability of depression (Peveler et al 1995, Waller and Shaw 1995). In these studies, no differences in mood-related symptoms were identified in women with chronic pelvic pain with or without endometriosis. Antidepressant therapy may be indicated in order to alleviate depression, but sertraline was not effective for pelvic pain in a recent small but well-conducted randomized trial (Engel et al 1998).

Abuse and somatization

Child sexual or physical abuse may be an antecedent for chronic pelvic pain, but many individuals have suffered such abuse without this or other consequences in later life, and the research literature is beset with the problem of appropriate comparison groups. A study from a tertiary referral multidisciplinary clinic setting reported on the full assessment of psychological factors in three groups of 30 women with chronic pelvic pain, chronic pain of other types, or without pain identified from general practitioner records. Twelve (40%) of those with chronic pelvic pain reported sexual abuse, compared with five (17%) in each of the two comparison groups. Experience of physical violence was similar in the three groups, but women with chronic pelvic pain had higher scores for somatization, meaning the experience and communication of distress and physical symptoms without clear underlying pathology. In women with pelvic pain, abuse histories were evenly distributed among those with and without identified pelvic pathology such as endometriosis, but somatization scores were higher among those with identified pathology (Collett et al 1998). It has been suggested that the potential link between sexual abuse and pelvic pain might be that abuse is an observable marker for childhood neglect in general (Fry et al 1997), and this might explain the association in some studies with physical rather than sexual abuse (Rapkin et al 1990). With regard to mediators between abuse and pain experience, those who reported abuse were more likely to be distressed and anxious (Poleshuck et al 2005).

Identification of patients with features suggesting somatization disorder is important as failure to do so will lead to further inappropriate investigation, and treatment directed towards physical symptoms which are, in fact, manifestations of psychological distress. There are limited data regarding the prevalence of frank somatization disorder in clinic populations; in a study comparing the medical assessment with a standardized questionnaire, doctors identified 19% of patients as being potential somatizers, and approximately 5% met questionnaire criteria for overt somatization disorder (Peveler et al 1997). With regard to patients within the pelvic pain spectrum of conditions, the finding of Zolnoun et al (2008) of higher scores for somatization among patients with primary vulval vestibulitis compared with those with secondary vulval vestibulitis indicates a need for more detailed characterization of this propensity among the different clinical subpopulations.

Sociocultural Factors in Chronic Pelvic Pain

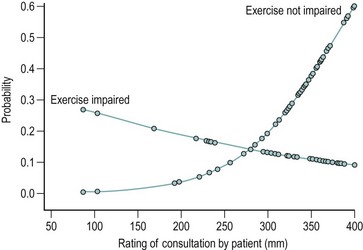

It could be argued that in life-threatening medical conditions or conditions where a technical solution gives excellent results, the patient’s experience of care and the quality of doctor–patient communication are not critical to the outcome. In contrast, in ill-defined, chronic conditions where a technical solution is unlikely to provide relief, sociocultural factors have a major influence on the patient’s decision to seek care and the referral pathway subsequently followed. The population-based studies cited above provide an indication of the size of the iceberg of symptoms below the waterline of care seeking. Similarly, in general practice, many women remain undiagnosed and unreferred. This is not necessarily inappropriate but the determinants of presentation and referral are unlikely to be disease factors alone. Once seen in a gynaecology clinic, the interaction between disease states and the consultation setting can be identified in statistical models; the presence of endometriosis was a factor predicting continuing pain 6 months after an initial hospital outpatient consultation, but so also were the patient’s initial report of pain interfering with exercise, her rating of the initial medical consultation as less satisfactory (Figure 61.2) and the individual clinician undertaking the consultation (but not the doctor’s grade or gender) (Selfe et al 1998a). The ability to establish a therapeutic rapport and meet the patient’s expectations during consultations, rather than simply convey information, may be factors that favour a good outcome (Stones et al 2006).

Often, problems are encountered not just with a particular individual clinician or aspect of care, but tend to accumulate for some patients as they move through the system. This seems to be more of a problem for women of low socioeconomic status (Grace 1995). A solution to this mismatch between women’s needs and the structures through which care is provided may be the multidisciplinary approach, which at least works against the crude compartmentalized organic/psychological causation model, although it has been suggested that a more fundamental reconsideration of the medical paradigm is required (Grace 1998). Meanwhile, within the practical constraints of time, lack of continuity of care in the hospital setting and very limited access to multidisciplinary resources, gynaecologists can at least recognize the potential impact of their own attitudes and communication styles (Selfe et al 1998b).

Clinical Assessment

Pain history

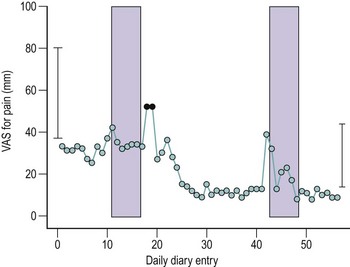

A number of validated pain assessment measures are available for use in research and clinical practice, the most convenient of which are the 10 cm visual analogue scale, the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and the McGill Short Form pain questionnaire. The McGill questionnaire is included in the International Pelvic Pain Society’s assessment form, available for downloading at www.pelvicpain.org; the BPI may be downloaded at mdanderson.org/departments/PRG/. Patients’ recall of pain symptoms over the previous month seems to be adequate, and it is probably unnecessary to ask for a daily pain diary: 10 cm visual analogue scales for ‘usual’ and ‘most severe’ intensity of pain recalled over the past 4 weeks correlated very well with mean and maximal diary records (Figure 61.3) (Stones et al 2001).

Impact on quality of life

At present, a validated illness-specific instrument is not available for assessing quality of life and functional impairment in women with pelvic pain. Simple questions about the effect of the pain on work, leisure, sleep and sexual relationships are nevertheless useful. A generic quality of life measure such as the SF-36 may be used for monitoring outcomes. The SF-36 is somewhat problematic when used in episodic conditions such as menorrhagia (Jenkinson et al 1996b), but has face validity and reliability in chronic pelvic pain (Stones et al 2000).

Sexual and physical abuse

The extent to which clinicians can or should attempt to elicit a history of sexual or physical abuse during a gynaecological consultation is a matter for judgement in relation to the setting, in particular the follow-up and support that are available to women following such disclosure. The history may be volunteered unprompted by the patient, particularly during a subsequent consultation when rapport has been established. Some women may even find it easier to raise the subject with an unfamiliar specialist than with a general practitioner with whom they have regular consultations for other matters. It may be useful to incorporate questions on abuse into a self-completion questionnaire, such as that provided by the International Pelvic Pain Society, or in a multidisciplinary clinic to address the topic during a consultation with the nurse or psychologist (see Chapter 65 for more information).

Systems review

The history should be thorough with regards to symptoms potentially indicative of IBS; the poor outcome of patients with IBS referred to gynaecology clinics has been emphasized (Prior and Whorwell 1989). It is unlikely that dyspareunia can be attributed to IBS; bowel spasm perhaps accounts for the experience of those patients who describe an interval between the end of intercourse and the onset of acute pain (Whorwell 1995) associated with the urge to defaecate and abdominal distension. Pain associated with micturition or a full bladder should be enquired about, as there may be some overlap between chronic pelvic pain and the interstitial cystitis spectrum discussed in Chapter 56.

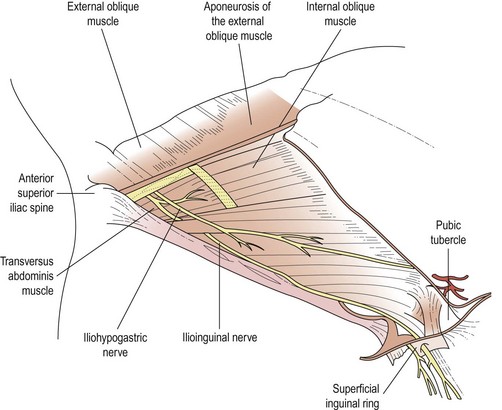

Physical examination

Observing the patient as she walks may give an indication of a musculoskeletal problem, and examination of the back is relevant in those giving a history of pain radiating or originating in this area. Abdominal examination may reveal specific sites of tenderness. One-finger ‘trigger point’ tenderness will suggest a nerve entrapment, often involving the ilioinguinal or iliohypogastric nerves. These can develop spontaneously as well as following surgery. The diagnosis is confirmed after obtaining appropriate consent by infiltration of local anaesthetic into the tender area. ‘Ovarian point’ tenderness has been described as a feature of pelvic congestion syndrome (Beard et al 1988), but this sign is problematic in patients with IBS who often have similar abdominal tenderness. A general neurological examination is appropriate to exclude a systemic neuropathy or demyelination; if abnormalities are present, a neurology opinion should be sought.

Vaginal examination should commence with a careful inspection of the vulva and introitus, paying particular attention to the presence of erythema which might suggest primary vulval vestibulitis (Gibbons 1998) (see Chapter 40). More frequently, no erythema is evident but a gentle touch with a cotton-tipped swab in the area just external to the hymeneal ring elicits intense sharp pain, even in patients who do not complain of dyspareunia. This allodynia in the absence of visible erythema probably represents referred sensation from painful areas higher in the pelvis, but represents the primary problem for some women. Vulval varices may indicate incompetence of valves in the pelvic venous circulation; this subgroup of patients may benefit from radiological assessment and treatment (see below).

Investigations

It is helpful to discount active pelvic infection, especially the presence of chlamydia, early in the assessment by taking endocervical swabs. Ultrasound examination may be useful in identifying uterine or adnexal pathology. The presence of dilated veins may indicate pelvic congestion (Stones et al 1990), but a recent study using power Doppler suggested that the primary value of sonography was to identify the characteristic multicystic ovarian morphology seen in this condition (Halligan et al 2000). Transuterine venography is of limited value in routine clinical practice, but is technically simpler than selective catheterization of the ovarian vein. Magnetic resonance imaging provides the opportunity to identify adenomyosis but is not indicated routinely.

Laparoscopy is commonly undertaken as the primary investigation for chronic pelvic pain in many countries. The aim of laparoscopy is to aid diagnosis but also, increasingly, to provide ‘one-stop’ treatment for endometriosis and adhesions where these are identified. This approach is cost-effective for endometriosis treatment, as the expense of a second procedure or hormonal treatment is obviated (Stones and Thomas 1995). However, given the potential for confusion arising from a ‘negative’ laparoscopy (Howard 1996) and the lack of a clear impact of recourse to laparoscopy on outcome at the referral population level (Peters et al 1991, Selfe et al 1998b), arguments in favour of deferring laparoscopy, at least until initial symptomatic treatment has failed, take on some force. The impetus for treatment using gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists without laparoscopic diagnosis has emanated from the US-managed care environment (Winkel 1999), and from retrospective assessment of outcomes in the UK (Lyall et al 1999). For clinical practice, the timing of laparoscopy is a matter for discussion with the patient based on her needs for diagnosis and treatment, and the overall context of treatment modalities available.

Pain mapping by laparoscopy under conscious sedation can be a useful procedure, particularly where the site of pain is unilateral, allowing comparison with a ‘control’ area to assess the significance of adhesions, to identify unrecognized occult inguinal or femoral hernias, and in the negative sense to identify individuals with a generalized hyperalgesic chronic pain state for whom further surgical intervention would be hazardous. The choice of instrumentation represents a trade-off between the lower quality field of view available from a 2 mm laparoscope and patient discomfort associated with a larger trocar and cannula. In practice, a 5 mm laparoscope does not cause significantly more pain than the smaller instruments. Following early reports of experience (Howard 1999), there are indications that clinical outcomes can be improved for some patients where conventional approaches have not proved successful and the laparoscopic findings have been unclear (Swanton et al 2006).

Diagnosis and Treatment: Specific Conditions

There is limited evidence from randomized clinical trials on which to base treatment decisions for women with chronic pelvic pain (Stones et al 2005). An approach to specific conditions is outlined below.

Pelvic congestion syndrome

This condition may be considered a clinical syndrome based on the characteristic symptom complex described by Beard et al (1988). Pelvic congestion is typically a condition of the reproductive years and, in contrast to endometriosis, is equally prevalent among parous and nulliparous women. There may be an underlying endocrine dysfunction, although peripheral hormone levels are not abnormal. The associated ovarian morphology is characterized by predominantly atretic follicles scattered throughout the stroma, while in contrast to polycystic ovary syndrome, the volume of the ovary is normal. The thecal androstenedione response to luteinizing hormone was increased as in polycystic ovaries, but granulosa cell oestradiol production was reduced compared with normal tissue (Gilling-Smith et al 2000).

Symptoms include exacerbation of pain with prolonged standing, dyspareunia, postcoital aching and a fluctuating localization of pain. Patients may derive reassurance from being given the diagnosis as an explanation of their pain in terms of a functional condition similar to cerebral migraine. Therapy includes identification of stressors and the use of hormonal treatment in combination with stress and pain management, with the aim of encouraging the patient to make appropriate lifestyle changes so that her symptoms are less likely to recur on completion of a course of hormonal treatment. Medroxyprogesterone acetate 50 mg daily has been shown to be effective (Farquhar et al 1989), and GnRH agonists with oestrogen ‘add-back’ are increasingly used in this indication although randomized trial data are lacking to date. Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy followed by long-term oestrogen replacement therapy is an option for those who have extreme symptoms partially or temporarily relieved by hormonal therapy, but this is naturally a treatment of last resort (Beard et al 1991).

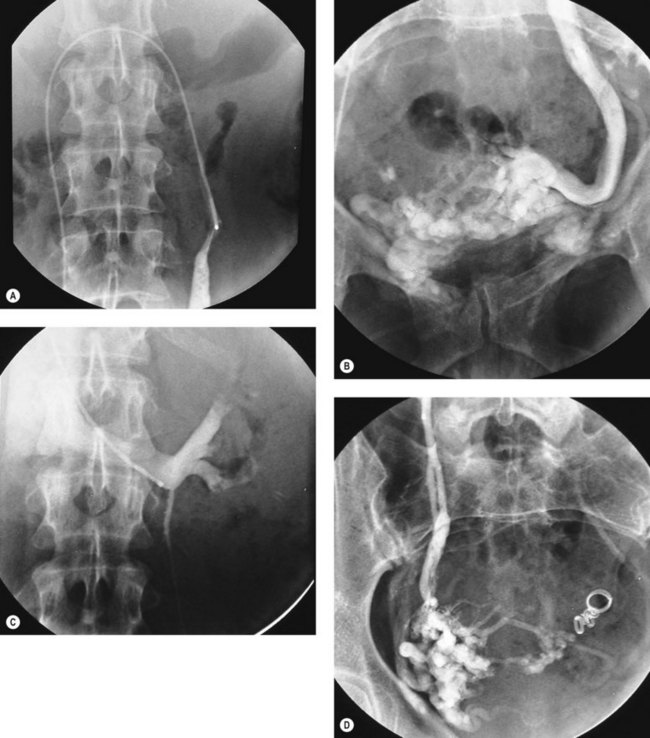

Patients with peripheral venous disease and vulval varicosities are probably manifesting a different clinical entity from those described above. A surgical approach involving extraperitoneal dissection of the ovarian veins has been described (Hobbs 1976), and this group of patients may benefit from current interventional radiology techniques for vein occlusion (Figure 61.4). However, the evidence for useful benefit in those without vulval or lower limb varices is restricted to series where definition of the case mix is not always clear.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is discussed in detail in Chapter 33. From the perspective of clinical practice in chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis presents special problems at both ends of the spectrum of disease severity. Women with endometriosis have poor outcomes compared with those with other conditions in terms of pain relief (Selfe et al 1998a), and they require careful attention to the provision of effective pain relief. Many women have undergone laparoscopy with the expectation of endometriosis being confirmed, and have difficulty coming to terms with the lack of a positive diagnosis when endometriosis is not found, as illustrated in the extract from a patient’s comments presented above.

Treatments which suppress or ablate endometriosis are, in general, associated with relief of pain. In the case of hormonal therapies, a major benefit is the suppression of menstruation, resulting in the prevention of dysmenorrhoea. Laparoscopic surgical ablation of deposits in stage I–III disease is associated with reduction in pain, as demonstrated in the single available randomized trial (Sutton et al 1994), and laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis also improves pain symptoms, quality of life and sexual function (Abbott et al 2004). There are insufficient data to make clear recommendations about the different available surgical approaches (e.g. laser vaporization vs excision and diathermy) with respect to pain outcomes.

The place of laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation, as opposed to ablation of visible deposits, remains unclear. More positive results have been reported for presacral neurectomy in primary dysmenorrhoea (Chen et al 1996, Nezhat et al 1998), which perhaps reflects the greater potential for interrupting sensory pathways to the uterus offered by this procedure. There is significant surgical risk associated with presacral neurectomy, and an incidence of complications, especially constipation, and the importance of high-level surgical skills has been emphasized (Perry and Perez 1993). In the light of the discussion of pain mechanisms earlier in this chapter, efforts to achieve pain relief by interruption of nerve pathways are probably naïve as they do not take into account the central nervous system contribution to the maintenance of chronic pain states following an initial inflammatory insult, of which endometriosis represents a good example.

Adhesions

Critical studies of the relationship between adhesions and pain suggest that they are often likely to be coincidental rather than causal (Rapkin 1986). Adhesiolysis by laparotomy was only effective for adhesions that were dense, vascularized or adherent to bowel (Peters et al 1992). Taking these findings together with those of Swank et al (2003) where laparoscopic treatment was employed, there is little evidence to support this approach (Stones et al 2005). As discussed above, pain mapping by laparoscopy under conscious sedation may be useful in identifying adhesions that are tender rather than asymptomatic, with due regard to the complexities of visceral sensory pathways previously reviewed and the sensitivity and discrimination of sensations from the pelvic organs under normal conditions (Koninckx and Renaer 1997). Laparoscopic adhesiolysis needs to be undertaken with particular care so as to avoid bowel injury, and with appropriate preoperative counselling and bowel preparation.

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease

In UK clinical practice, chronic PID should be a laparoscopic diagnosis based on the finding of tubal damage and signs of active infection. The true prevalence will vary depending on the referral population, but a diagnosis based on a clinical impression of pelvic tenderness and partial response to repeated courses of antibiotics is likely to be incorrect. This observation is also relevant for regions with a higher background prevalence of PID such as sub-Saharan Africa (Kasule 1991). Apart from not resolving her problem, incorrect labelling of a patient as suffering from chronic PID may lead the patient to adopt an extremely negative self-image, and inflict on her inappropriate anxiety about future fertility.

Nerve entrapment

The finding of abdominal wall tenderness which is consistently localized to a particular point should lead to consideration of a nerve entrapment. This predominantly involves the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves, the anatomy of which is illustrated in Figure 61.5, but genitofemoral nerve entrapment has also been described. A typical protocol for management includes establishing the diagnosis by infiltration of bupivacaine 0.25%, and demonstrating complete relief of pain and tenderness. This can be followed by one or two injections 1 month apart of bupivacaine and a long-acting corticosteroid such as Depo Medrone 40 mg. Surgical exploration and excision of the nerve can be undertaken with approximately 70% success (Hahn 1989, Lee and Dellon 2000). The response to an initial infiltration of bupivacaine is often much more prolonged than would be expected from the duration of action of the local anaesthetic, perhaps because minor perineural adhesions are broken down by the volume of the infiltration, or surrounding muscle spasm is relieved.

Neuropathic and postsurgical pelvic pain

A special instance of postsurgical pain where further surgery is indicated is ovarian remnant syndrome, where a fragment of active ovarian tissue generates pain through continued ovulatory activity. The diagnosis can be made by withdrawing oestrogen replacement therapy and demonstrating endogeneous hormone production, and the lesion can be localized by the administration of clomiphene or human menopausal gonadotropin prior to imaging. The surgery is technically challenging and is best approached by laparotomy rather than laparoscopy (Richlin and Rock 2001).

Hernias

Occult inguinal hernias have been recognized in women presenting with pain but without the normal swelling or cough impulse (Herrington 1975), but surgeons have naturally been reluctant to operate in the absence of more definite physical signs. Current surgical thinking on inguinal and femoral hernias, and rarities such as spigelian and obturator hernias, is reviewed by Daoud (1998). Inguinal and femoral hernias can readily be evaluated during pain mapping laparoscopy, as the anatomy can be easily visualized, localized tenderness can be detected, and laparoscopic repair can subsequently be undertaken.

Diagnostic overlap and ‘no diagnosis’

Despite the best efforts of clinicians to identify specific causes of pelvic pain, it will be unclear how to classify many patients. In a consecutive series of 98 patients referred for investigation by their general practitioner, diagnoses were endometriosis (n = 12), adhesions (n = 10) and other gross pathology (n = 15). No positive diagnosis could be established in 29 patients. Three or more IBS symptoms were present in 15 patients, but there was overlap with other diagnoses in 13 of these patients. A symptom complex suggestive of pelvic congestion syndrome was present in 57 patients, but this overlapped with seven cases of endometriosis, six cases of adhesions, eight cases of gross pathology and nine cases of IBS (Selfe et al 1998b). Similar findings of no positive diagnosis and diagnostic overlap were noted in women consulting in primary care (Zondervan et al 1999a), and self-reports of symptoms and received diagnoses in a population survey (Zondervan et al 2001a).

Management Settings and Strategies

An important step in formulating a management plan for any patient is to establish her treatment goals, especially whether she is primarily concerned with identifying a cause for her pain or is less concerned with causation but desires rapid symptomatic relief. In the former instance, further investigation such as laparoscopy may help the patient towards her goal, whereas in the latter case, initial symptomatic treatment may be more appropriate. Further clarification may be required regarding the relative priority that the patient gives to pain relief and restoration of normal function. The impact of a well-conducted and sympathetic consultation may itself be therapeutic based on some of the research discussed above; indeed, ultrasonography has been used effectively as a means of providing reassurance (Ghaly 1994).

For patients at the more severe end of the illness spectrum, the elements of a pain management approach become more important; randomized trial evidence supports multidisciplinary care (Peters et al 1991). Multidisciplinary care may include contributions from other disciplines including anaesthesia, psychology, physiotherapy, nursing and liaison psychiatry. The analgesic regimen is optimized, bearing in mind that 6–10% of the Caucasian population are unable to metabolize codeine (Eckhardt et al 1998), and full use is made of adjunctive agents such as amitriptyline 10–50 mg at night or gabapentin in an incremental regimen from 400 to 3600 mg daily. The latter agent is indicated for neuropathic pain and does not interact with the oral contraceptive pill, but has adverse effects of giddiness and drowsiness. Randomized trials have shown gabapentin to be of benefit for pain relief in diabetic neuropathy and trigeminal neuralgia (Backonja et al 1998, Rowbotham et al 1998).

Outcomes from non-randomized studies of multidisciplinary management in North Carolina were positive; 46% of 370 patients reported pain improvement after 1 year, with similar outcomes in those who had received primarily medical treatment (including psychological input) or primarily surgical treatment (Lamvu et al 2006). On the other hand, in Holland, 3-year follow-up of a cohort of 72 patients seen in a multidisciplinary clinic revealed a majority with continuing symptoms, pointing to the need for ongoing care for a chronic condition rather than a high expectation of cure (Weijenborg et al 2007).

Where mood disturbance is identified, concomitant antidepressant therapy should be suggested. Where there are indications of more complex psychopathology, particularly somatoform disorder, a liaison psychiatry opinion is appropriate. The rate of attendance by gynaecological patients referred to psychiatric departments is extremely low, and there are considerable advantages to service models which enable cross-referral on the same premises at short notice; however, these often present practical problems. Psychological assessment itself has therapeutic value (Price and Blake 1999), and a psychologist or psychotherapist can provide guidance on pain and/or stress management and motivate patients to move from passivity to active participation in their treatment. Wherever possible, patients should be offered the opportunity of a structured programme of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), as evidence for the benefit of this approach is strong. Taking the rigorous approach of identifying ‘clinically significant change’ as an endpoint for outcomes in a routine clinical setting, between one in three and one in seven patients seen in a UK chronic pain clinic experienced useful benefits from CBT (Morley et al 2008).

Abbott J, Hawe J, Hunter D, Holmes M, Finn P, Garry R. Laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertility and Sterility. 2004;82:878-884.

Backonja M, Beydoun A, Edwards K, et al. Gabapentin for the symptomatic treatment of painful neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus — a randomized controlled trial. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1831-1836.

Beard RW, Reginald PW, Wadsworth J. Clinical features of women with chronic lower abdominal pain and pelvic congestion. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1988;95:153-161.

Beard RW, Kennedy RG, Gangar KF, et al. Bilateral oophorectomy and hysterectomy in the treatment of intractable pelvic pain associated with pelvic congestion. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1991;98:988-992.

Berkley K, Hubscher CH. Are there separate central nervous system pathways for touch and pain? Nature Medicine. 1995;1:766-773.

Berkley KJ, McAllister SL, Accius BE, Winnard KP. Endometriosis-induced vaginal hyperalgesia in the rat: effect of estropause, ovariectomy, and estradiol replacement. Pain. 2007;132(Suppl 1):S150-S159.

Bon K, Lanteri-Minet M, Menetrey D, Berkley KJ. Sex, time-of-day and estrous variations in behavioral and bladder histological consequences of cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis in rats. Pain. 1997;73:423-429.

Bradshaw HB, Temple JL, Wood E, Berkley KJ. Estrous variations in behavioral responses to vaginal and uterine distention in the rat. Pain. 1999;82:187-197.

Chen FP, Chang SD, Chu KK, Soong YK. Comparison of laparoscopic presacral neurectomy and laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation for primary dysmenorrhea. Journal of Reproductive Medicine for the Obstetrician and Gynecologist. 1996;41:463-466.

Collett BJ, Cordle CJ, Stewart CR, Jagger C. A comparative study of women with chronic pelvic pain, chronic nonpelvic pain and those with no history of pain attending general practitioners. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105:87-92.

Daoud I. General surgical aspects. In: Steege JF, Metzger DA, Levy BS, editors. Chronic Pelvic Pain: an Integrated Approach. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998:329-336.

Davies L, Gangar KF, Drummond M, Saunders D, Beard RW. The economic burden of intractable gynaecological pain. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1992;12(Suppl 2):S54-S56.

Dickenson AH. Plasticity: implications for opioid and other pharmacological interventions in specific pain states. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1997;20:392-403.

Dworkin SF, Von-Korff M, LeResche L. Multiple pains and psychiatric disturbance. An epidemiologic investigation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:239-244.

Eckhardt K, Li SX, Ammon S, Schanzle G, Mikus G, Eichelbaum M. Same incidence of adverse drug events after codeine administration irrespective of the genetically determined differences in morphine formation. Pain. 1998;76:27-33.

Engel CC, Walker EA, Engel AL, Bullis J, Armstrong A. A randomized, double-blind crossover trial of sertraline in women with chronic pelvic pain. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1998;44:203-207.

Farquhar CM, Rogers V, Franks S, Pearce S, Wadsworth J, Beard RW. A randomized controlled trial of medroxyprogesterone acetate and psychotherapy for the treatment of pelvic congestion. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1989;96:1153-1162.

Fillingim RB, Edwards RR, Powell T. The relationship of sex and clinical pain to experimental pain responses. Pain. 1999;83:419-425.

Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Kincaid S, Silva S. Sex differences in temporal summation but not sensory-discriminative processing of thermal pain. Pain. 1998;75:121-127.

Fry RPW, Beard RW, Crisp AH, McGuigan S. Sociopsychological factors in women with chronic pelvic pain with and without pelvic venous congestion. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1997;42:71-85.

Ghaly AFF. The psychological and physical benefits of pelvic ultrasonography in patients with chronic pelvic pain and negative laparoscopy. A random allocation trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;14:269-271.

Gibbons JM. Vulvar vestibulitis. In: Steege JF, Metzger DA, Levy BS, editors. Chronic Pelvic Pain: an Integrated Approach. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998:181-187.

Gilling-Smith C, Mason H, Willis D, Franks S, Beard RW. In-vitro ovarian steroidogenesis in women with pelvic congestion. Human Reproduction. 2000;15:2570-2576.

Grace VM. Problems of communication, diagnosis, and treatment experienced by women using the New Zealand health services for chronic pelvic pain: a quantative analysis. Health Care for Women International. 1995;16:521-535.

Grace VM. Mind/body dualism in medicine: the case of chronic pelvic pain without organic pathology — a critical review of the literature. International Journal of Health Services. 1998;28:127-151.

Hahn L. Clinical findings and results of operative treatment in ilioinguinal nerve entrapment syndrome. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1989;96:1080-1083.

Halligan S, Campbell D, Bartram CI, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound examination of women with and without pelvic venous congestion. Clinical Radiology. 2000;55:954-958.

Herrero JF, Laird JMA, Lopez-Garcia JA. Wind-up of spinal cord neurones and pain sensation: much ado about something? Progress in Neurobiology. 2000;61:169-203.

Herrington JK. Occult inguinal hernia in the female. Annals of Surgery. 1975;181:481-483.

Hobbs JT. The pelvic congestion syndrome. The Practitioner. 1976;216:529-540.

Horn S, Munafo M. Pain Theory, Research, and Intervention. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997.

Howard FM. The role of laparoscopy in the evaluation of chronic pelvic pain: pitfalls with a negative laparoscopy. Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. 1996;4:85-94.

Howard FM. Pelvic pain. In: Thomas EJ, Stones RW, editors. Gynaecology Highlights 1998–99. Oxford: Health Press; 1999:53-63.

IASP Task Force on Taxonomy. Classification of Chronic Pain, 2nd edn. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994.

Jenkinson C, Layte R, Wright L, Coulter A. The UK SF-36: an Analysis and Interpretation Manual. Oxford: Health Services Research Unit, University of Oxford; 1996.

Jenkinson C, Peto V, Coulter A. Making sense of ambiguity: evaluation of internal reliability and face validity of the SF-36 questionnaire in women presenting with menorrhagia. Quality in Health Care. 1996;5:9-12.

Kasule J. Laparoscopic evaluation of chronic pelvic pain in Zimbabwean women. East African Medical Journal. 1991;68:807-811.

Koninckx PR, Renaer M. Pain sensitivity of and pain radiation from the internal female genital organs. Human Reproduction. 1997;12:1785-1788.

Lamvu G, Williams R, Zolnoun D, Wechter ME, Shortliffe A, flton G, Steege JF. long-term outcomes after surgical and nonsurgical management of chronic pelvic pain: one year after evaluation in a pelvic pain specialty clinic. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;195:591-598.

Lee CH, Dellon AL. Surgical management of groin pain of neural origin. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2000;191:137-142.

Lyall H, Campbell-Brown M, Walker JJ. GnRH analogue in everyday gynecology: is it possible to rationalize its use? Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1999;78:340-345.

Mathias SD, Kuppermann M, Liberman RF, Lipschutz RC, Steege JF. Chronic pelvic pain: prevalence, health-related quality of life, and economic correlates. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;87:321-327.

McMahon SB. Are there fundamental differences in the peripheral mechanisms of visceral and somatic pain? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1997;20:381-391.

Morley S, Williams A, Hussain S. Estimating the clinical effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy in the clinic: evaluation of a CBT informed pain management programme. Pain. 2008;137:467-468.

Nezhat CH, Seidman DS, Nezhat FR, Nezhat CR. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic presacral neurectomy for the treatment of central pelvic pain attributed to endometriosis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;91:701-704.

Perry CP, Perez J. The role for laparoscopic presacral neurectomy. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. 1993;9:165-168.

Peters AA, van Dorst E, Jellis B, van Zuuren E, Hermans J, Trimbos JB. A randomized clinical trial to compare two different approaches in women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;77:740-744.

Peters AAW, Trimbos-Kemper GCM, Admiraal C, Trimbos JB. A randomized clinical trial on the benefit of adhesiolysis in patients with intraperitoneal adhesions and chronic pelvic pain. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1992;99:59-62.

Peveler R, Edwards J, Daddow J, Thomas EJ. Psychosocial factors and chronic pelvic pain: a comparison of women with endometriosis and with unexplained pain. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1995;40:305-315.

Peveler R, Kelkenny L, Kinmonth A-L. Medically unexplained physical symptoms in primary care: a comparison of self-report screening questionnaires and clinical opinion. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1997;42:245-252.

Poleshuck EL, Dworkin RH, Howard FM, et al. Contributions of physical and sexual abuse to women’s experiences with chronic pelvic pain. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2005;50:91-100.

Price JR, Blake F. Chronic pelvic pain: the assessment as therapy. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1999;46:7-14.

Prior A, Whorwell PJ. Gynaecological consultation in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1989;30:996-998.

Rapkin AJ. Adhesions and pelvic pain: a retrospective study. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1986;68:13-15.

Rapkin AJ, Kames LD, Darke LL, Stampler FM, Naliboff BD. History of physical and sexual abuse in women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;76:92-96.

Richlin SS, Rock JA. Ovarian remnant syndrome. Gynaecological Endoscopy. 2001;10:111-117.

Riley JL, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Price DD. A meta-analytic review of pain perception across the menstrual cycle. Pain. 1999;81:225-235.

Rowbotham M, Harden N, Stacey B, Bernstein P, Magnus Miller L. Gabapentin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia — a randomized controlled trial. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1837-1842.

Selfe SA, Matthews Z, Stones RW. Factors influencing outcome in consultations for chronic pelvic pain. Journal of Women’s Health. 1998;7:1041-1048.

Selfe SA, van Vugt M, Stones RW. Chronic gynaecological pain: an exploration of medical attitudes. Pain. 1998;77:215-225.

Shabalina SA, Zaykin DV, Gris P, et al. Expansion of the human mu-opioid receptor gene architecture: novel functional variants. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009;18:1037-1051.

Slocumb JC, Kellner R, Rosenfeld RC, Pathak D. Anxiety and depression in patients with the abdominal pelvic pain syndrome. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1989;11:48-53.

Stones RW. Chronic pelvic pain in women: new perspectives on pathophysiology and management. Reproductive Medicine Review. 2000;8:229-240.

Stones RW, Rae T, Rogers V, Fry R, Beard RW. Pelvic congestion in women: evaluation with transvaginal ultrasound and observation of venous pharmacology. British Journal of Radiology. 1990;63:710-711.

Stones RW, Thomas EJ. Cost-effective medical treatment of endometriosis. In: Bonnar J, editor. Recent Advances in Obstetrics and Gynaecology 19. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:139-152.

Stones RW, Selfe SA, Fransman S, Horn SA. Psychosocial and economic impact of chronic pelvic pain. Baillière’s Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;14:27-43.

Stones RW, Bradbury L, Anderson D. Randomized placebo controlled trial of lofexidine hydrochloride for chronic pelvic pain in women. Human Reproduction. 2001;16:1719-1721.

Stones RW, Cheong Y, Howard FM 2005 Interventions for treating chronic pelvic pain in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD000387.

Stones RW, Lawrence WT, Selfe SA. Lasting impressions: influence of the initial hospital consultation for chronic pelvic pain on dimensions of patient satisfaction at follow-up. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;60:163-167.

Sutton JG, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild and moderate endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility. 1994;62:696-700.

Swank DJ, Swank-Bordewijk SC, Hop WC, et al. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis in patients with chronic abdominal pain: a blinded randomised controlled multi-centre trial. The Lancet. 2003;361:1247-1251.

Swanton A, Iyer L, Reginald PW. Diagnosis, treatment and follow up of women undergoing conscious pain mapping for chronic pelvic pain: a prospective cohort study. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113:792-796.

Treloar SA, Martin NG, Heath AC. Longitudinal genetic analysis of menstrual flow, pain, and limitation in a sample of Australian twins. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28:107-116.

von Bahr V. Local anaesthesia for inguinal herniorrhaphy. In: Eriksson E, editor. Illustrated Handbook in Local Anaesthesia. 2nd edn. London: Lloyd-Luke; 1979:52-54.

Waller KG, Shaw RW. Endometriosis, pelvic pain, and psychological functioning. Fertility and Sterility. 1995;63:796-800.

Weijenborg PT, Greeven A, Dekker FW, Peters AA, Ter Kuile MM. Clinical course of chronic pelvic pain in women. Pain. 2007;132(Suppl 1):S117-S123.

Weijenborg PT, Ter Kuile MM, Gopie JP, Spinhoven P. Predictors of outcome in a cohort of women with chronic pelvic pain — a follow-up study. European Journal of Pain. 2008;13:769-775.

Whorwell P. The gender influence. Women and IBS. 1995;2:2-3.

Winkel CA. Modeling of medical and surgical treatment costs of chronic pelvic pain: new paradigms for making clinical decisions. American Journal of Managed Care. 1999;5:S276-S290.

Wise EA, Riley JL, Robinson ME. Clinical pain perception and hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women experiencing orofacial pain. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2000;16:121-126.

Woolf CJ. Evidence for a central component of post-injury pain hypersensitivity. Nature. 1983;306:686-688.

Woolf CJ, Shortland P, Coggeshall RE. Peripheral nerve injury triggers central sprouting of myelinated afferents. Nature. 1992;355:75-78.

Yonkers KA, Chantilis SJ. Recognition of depression in obstetric/gynecology practices. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;173:632-638.

Zolnoun D, Park EM, Moore CG, Liebert CA, Tu FF, As-Sanie S. Somatization and psychological distress among women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2008;103:38-43.

Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Patterns of diagnosis and referral in women consulting for chronic pelvic pain in UK primary care. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106:1156-1161.

Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106:1149-1155.

Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, et al. Chronic pelvic pain in the community — symptoms, investigations, and diagnoses. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;184:1149-1155.

Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, et al. The community prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in women and associated illness behaviour. British Journal of General Practice. 2001;51:541-547.