Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and restrictive lung disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

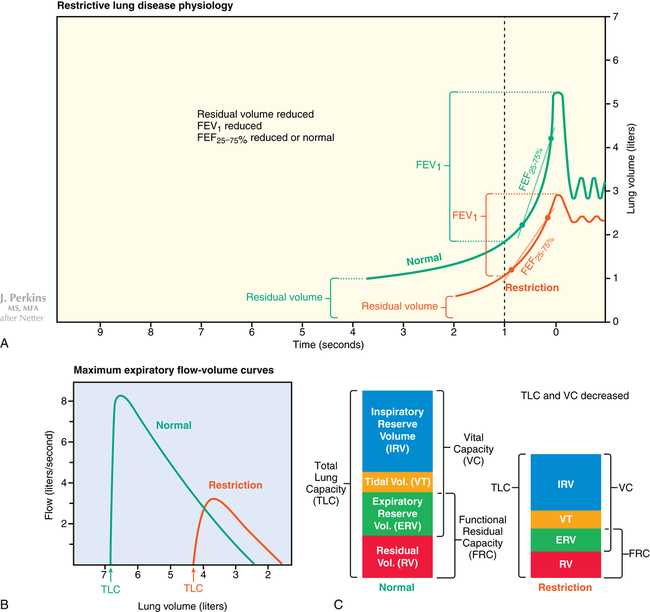

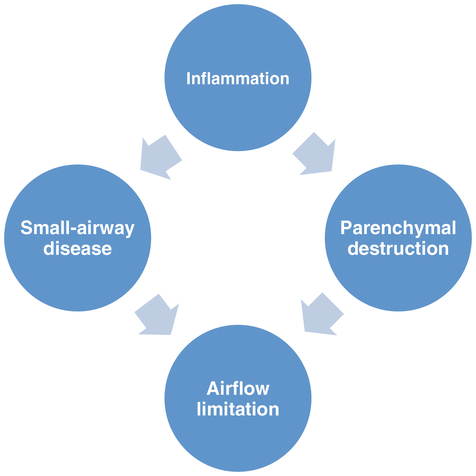

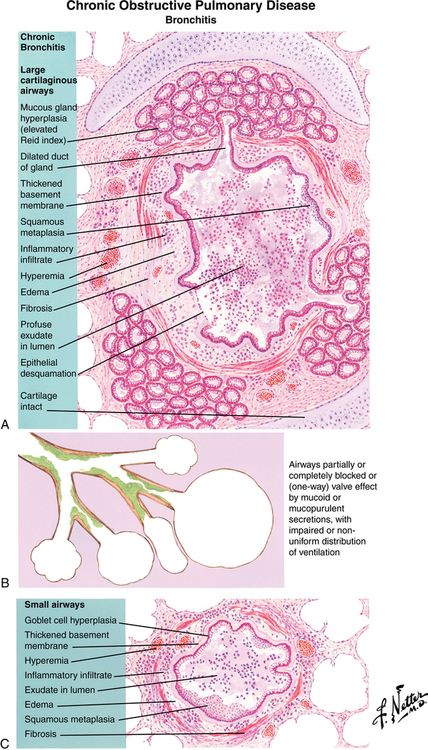

Patients with COPD frequently have a combination of obstructive bronchiolitis or small-airway disease and parenchymal destruction or emphysema (Figure 31-1). A ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 sec (FEV1) to functional vital capacity (FVC) of less than 0.7 is essential to make the diagnosis of COPD. Total lung capacity, residual volume, and functional residual capacity are all increased in COPD, which is different from the pattern seen with restrictive lung disease.

Clinical features

The Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease has calculated the prevalence of COPD to be 6.1% and 13.5%, respectively, after 9-year and 10-year cumulative studies. In young adults, the prevalence was found to be 2.2%, and in patients 40 to 44 years of age, it was 4.4%. The primary cause of COPD is cigarette smoking (with α1-antitrypsin deficiency as another cause in the young). Approximately half of patients older than 60 years of age who have a smoking history of at least 20 pack-years have a spirometry result consistent with COPD. Lung parenchymal destruction leads to loss of diffusing capacity and loss of the radial traction force on the airways. Airway inflammation produces increased mucus secretions and mucosal thickening, resulting in ventilation-perfusion mismatch and, finally, hypoxemia and CO2 retention. Airway collapse on expiration results in air trapping, leading to dynamic hyperinflation because of auto-positive end-expiratory pressure (Figure 31-2).

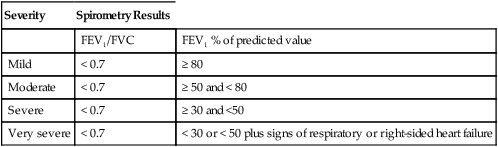

Signs and symptoms of COPD vary from asymptomatic to overt disease, depending on the severity of the disease (Table 31-1). Extrapulmonary symptoms include diaphragmatic dysfunction, right-sided heart failure, anxiety, depression, and weight loss with evidence of malnutrition.

Table 31-1

GOLD Classification of COPD Severity

| Severity | Spirometry Results | |

| FEV1/FVC | FEV1 % of predicted value | |

| Mild | < 0.7 | ≥ 80 |

| Moderate | < 0.7 | ≥ 50 and < 80 |

| Severe | < 0.7 | ≥ 30 and <50 |

| Very severe | < 0.7 | < 30 or < 50 plus signs of respiratory or right-sided heart failure |

Restrictive lung disease

Clinical features

Limited lung expansion or restrictive lung disease may result from any of several pulmonary and extrapulmonary causes—pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis, obesity, pleural effusion, scoliosis, or respiratory muscle weakness. Interstitial edema and acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ALI/ARDS) are classified as acute restrictive lung diseases. Spirometry can help differentiate between obstructive and restrictive patterns: in the latter, total lung capacity is reduced, airway resistance is normal, and airflow is preserved. Reduced FEV1 with a normal or increased FEV1/FVC suggests the presence of restrictive lung disease, but the diagnosis and severity grading are based on measurement of decreased total lung capacity (Figure 31-3). In patients who have restrictive lung disease with an intrinsic cause, reduced gas transfer is manifest as desaturation after exercise.