Chronic inflammatory disorders of the bowel

Introduction

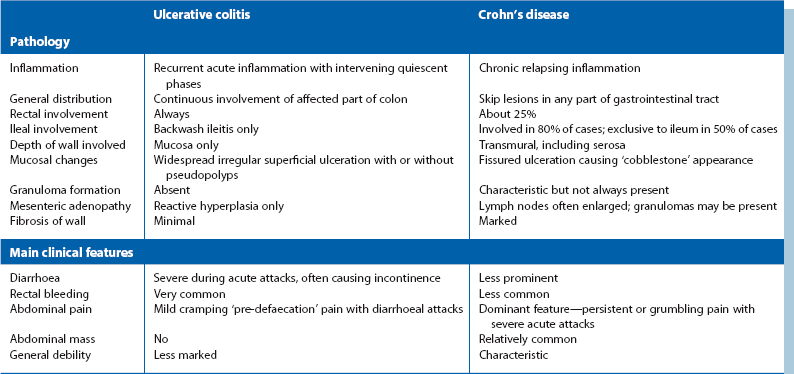

The term inflammatory bowel disease usually means the two chronic bowel disorders, ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. They share many pathophysiological and clinical features. However, Crohn’s disease can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract, whilst ulcerative colitis is confined to the large bowel. When the large bowel alone is inflamed, it is important to differentiate between these conditions because management and the spectrum of complications differ substantially (see Table 28.1).

Pseudomembranous and other forms of antibiotic-related colitis are increasingly common in hospitalised patients after antibiotic treatment; they are discussed in Chapter 12. Whilst typical cases can be readily diagnosed and treated, severe forms may require emergency colectomy and may cause fatality in elderly patients. Symptoms may occur as long as 6 months after antibiotic use.

Ulcerative Colitis

Pathophysiology of ulcerative colitis

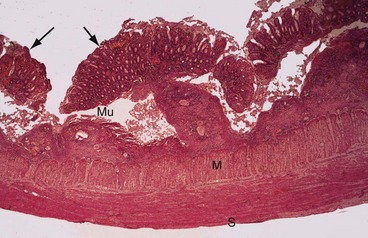

Initially, the colonic mucosa becomes acutely inflamed. Neutrophils accumulate in the lamina propria and within the tubular colonic glands to form small, highly characteristic crypt abscesses. Sloughing of the overlying mucosa produces small superficial ulcers. If the inflammatory process persists, the ulcers coalesce into extensive areas of irregular ulceration. Residual islands of intact but oedematous mucosa project into the bowel lumen; these inflammatory lesions are called pseudopolyps (see Fig. 28.1). The inflammation is usually confined to the mucosa and submucosa, only extending into the muscular wall and peritoneal surface in fulminating colitis.

Fig. 28.1 Ulcerative colitis—histopathology

Erosion and undermining of the mucosa Mu by the inflammatory process has produced typical pseudopolyps (arrowed). Inflammation spares the muscle wall M and serosa S. Mucosal glands show reactive and regenerative changes

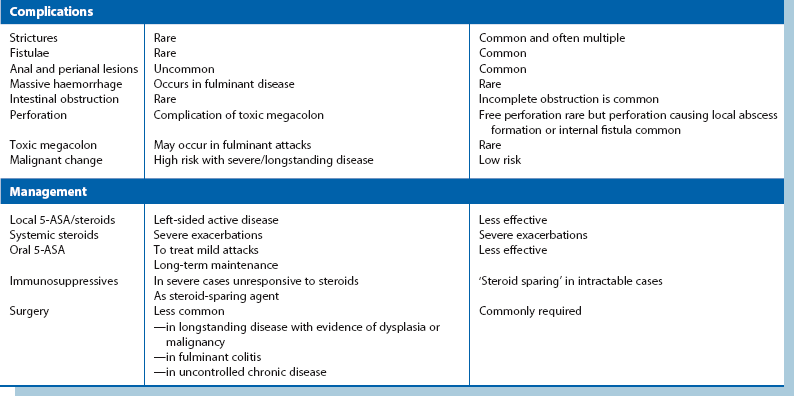

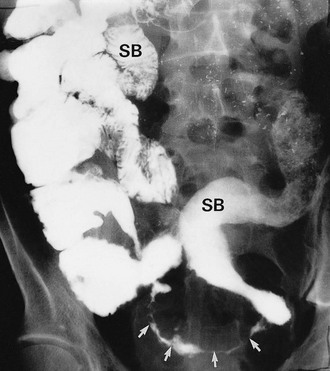

In longstanding colitis, the mucosa and submucosa undergo fibrosis, resulting in smoothing out of haustrations and a shortened colon which has a characteristic radiological appearance, the so-called lead pipe colon (Fig. 28.2).

Clinical features of ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis should probably be regarded as a systemic disorder. It is sometimes accompanied by extra-gastrointestinal manifestations, summarised in Box 28.1. During active phases, inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP)) are elevated and moderate anaemia and hypoalbuminaemia is common. Associated arthropathy, eye and skin disorders usually flare up in parallel with the colitis (although they may rarely precede the intestinal symptoms). However, the liver-related conditions—sclerosing cholangitis, chronic active hepatitis and bile duct carcinoma—are often independent of colitic activity and are therefore difficult to treat.

Clinical examination and investigation of suspected ulcerative colitis

Proctitis: Some patients with ulcerative colitis have inflammation confined to the lower rectum. The mucosa often has a granular appearance and the condition is described as proctitis or granular proctitis. Its cause is unknown and its course is self-limiting. It tends to recur at times of stress, often at protracted intervals. Proctitis usually responds to short courses of local 5-aminosalicylic acid suppositories (see later), but can occasionally progress into a distal or even a total colitis.

Contrast radiology: If the clinical picture and histological findings are consistent with inflammatory bowel disease, the extent and degree of colonic involvement can be assessed by barium enema examination. Radiological appearances are illustrated in Figures 28.2 and 28.3. Contrast radiology is not usually performed in acute disease.

Endoscopy: In an acute situation, an unprepared flexible sigmoidoscopy is usually performed. In non-acute situations, colonoscopy enables direct inspection of the entire colonic mucosa and the taking of multiple biopsies (see Fig. 28.4). Furthermore, in patients with longstanding total colitis, colonoscopy with narrow band imaging and multiple biopsies is used for annual surveillance for dysplastic change.

Fulminant ulcerative colitis: Fulminant attacks sometimes occur, with extremely frequent watery, blood-stained stools and severe systemic illness. An attack may progress to toxic dilatation and eventual colonic perforation. Urgent colectomy may be judged necessary to treat fulminant colitis resistant to medical therapy, or to treat toxic megacolon, once infective causes have been excluded.

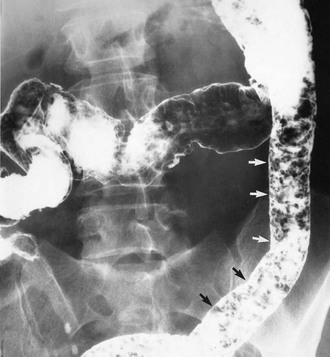

Whatever the cause, patients with acute colitis require urgent hospital admission and resuscitation including fluid, electrolyte and blood replacement. Sigmoidoscopy and biopsy are performed to establish the diagnosis. Stool is sent for microscopy and culture. Plain abdominal radiography is performed to monitor for dilatation, which might indicate toxic megacolon (defined as a colonic diameter greater than 6 cm in the presence of pyrexia or tachycardia). In the absence of megacolon, plain radiography may demonstrate other features of acute ulcerative colitis as shown in Figure 28.5.

Management of ulcerative colitis

The choice of treatment depends on the severity of individual attacks, the amount of colon involved, the extent of chronic symptoms and the risk of long-term complications. The treatment options are summarised in Box 28.2.

Aminosalicylate preparations: Mild attacks of proctitis or procto-sigmoiditis are treated locally with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) suppositories or enemas, which are more effective in acute proctitis than steroids. Mild attacks of pan-colitis are treated initially with oral 5-ASA preparations which are also employed as maintenance therapy in ulcerative colitis to prevent relapse. Although aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatories are chemically related to 5-ASA compounds, these drugs should be avoided as they may worsen inflammatory bowel disease. The 5-ASA compounds are discussed later in this chapter as they are also used in the management of Crohn’s disease.

Corticosteroids: Steroid suppositories or enemas (foam or liquid) can be used for local treatment of rectal inflammation. Short courses of high-dose oral corticosteroids are used for more severe exacerbations (e.g. prednisolone 40 mg daily for 2 weeks then reducing the daily dose by 5 mg weekly). Intravenous administration is advisable in seriously ill patients. There is no evidence that ‘bowel rest’ (i.e. nil by mouth) and total parenteral nutrition (TPN) are of any value in ulcerative colitis. Immunosuppressive drugs, including ciclosporin and azathioprine, are often tried in patients who fail to respond to corticosteroids. Azathioprine is also used as a ‘steroid-sparing’ agent in patients whose disease settles on steroids but flares again as steroids are reduced.

Other supportive measures: In the acute case, anti-diarrhoeal agents such as codeine phosphate or loperamide should be avoided as they can precipitate toxic dilatation.

Surgery for ulcerative colitis: Surgery is required in only about 20% of patients with ulcerative colitis. Colectomy may be needed in the following:

• Urgent treatment of fulminant cases which fail to respond to intensive medical treatment. ‘Failure to respond’ has no precise definition but there should normally be symptomatic improvement after a week of intensive management

• Acute cases which progress to toxic megacolon, perforation or major haemorrhage

• Patients with chronic disabling symptoms of intractable diarrhoea with urgency, recurring anaemia and failure to maintain adequate weight and nutrition

• Children with failure to thrive and retardation of growth (both are exacerbated by corticosteroid therapy)

• Patients with longstanding colitis who develop dysplasia or malignancy

As a principle, surgery for ulcerative colitis requires removal of the entire large bowel and is curative. There are three main surgical options:

• Subtotal colectomy with ileostomy is the safest operation in the emergency situation when the patient is sick and on high-dose corticosteroids. Most of the diseased colon is removed, but the patient is left with an inflamed rectal stump. Months later, when the patient is well, this may be revised to one of the other surgical options. Alternatively the rectum may be retained and treated with local therapy plus endoscopic surveillance, although the cancer risk remains

• Proctocolectomy with permanent ileostomy (includes removal of rectum) is generally recommended for elderly patients in whom sphincter-preserving procedures are inadvisable

• Restorative proctocolectomy (ileo-anal pouch, Parks’ pouch) is a sphincter-preserving operation which avoids a permanent ileostomy (see Fig. 27.8). The entire colon and rectal mucosa is excised and a pouch reservoir is fashioned from a loop of terminal ileum. The pouch is brought into the pelvis and anastomosed to the upper anal canal. A temporary ileostomy is usually retained for a few months to allow healing. Many patients have excellent continence and can evacuate their bowels in the normal way

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is a chronic relapsing inflammatory disorder of any part of the gastrointestinal tract (though nearly always small or large bowel) which predominantly affects younger people. About 60% of patients are under 25 years at the time of initial diagnosis, and on average, symptoms will have been present intermittently for 5 years. A useful website is http://www.crohns.org.uk/.

The disease often affects one or more discrete segments of bowel with intervening parts completely spared, unlike the continuous nature of ulcerative colitis. These discontinuous affected areas are known as ‘skip lesions’ (see Fig. 28.11, p. 373).

In contrast to ulcerative colitis, the inflammation involves the entire thickness of the bowel wall (transmural inflammation). Because of this, affected bowel may partially obstruct, fistulate or perforate, whereas this rarely occurs in ulcerative colitis. See Table 28.1 for comparisons between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Pathophysiology and clinical consequences of crohn’s disease

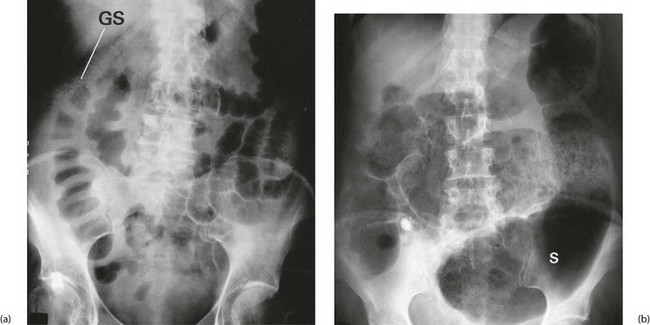

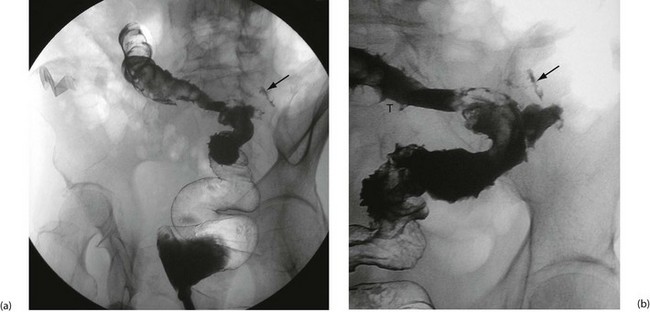

The essential pathological feature is chronic inflammation of bowel, with inflammation extending diffusely through the entire bowel wall. The wall becomes markedly thickened by inflammatory oedema, especially in the submucosa. The epithelium remains largely intact but is criss-crossed by deep fissured ulcers. These large serpiginous ulcers and the intervening areas of dome-shaped mucosa and submucosa give a typical ‘cobblestone’ surface appearance (Fig. 28.11).

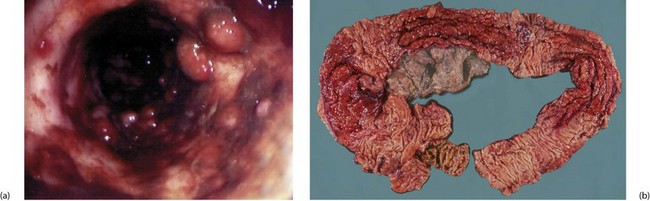

Fig. 28.11 Appearances of Crohn’s colitis

(a) This is a typical colonoscopic view of florid Crohn’s colitis. Note the nodular appearance producing a ‘cobblestone’ surface with linear ulcers between the nodules. (b) This subtotal colectomy specimen was removed from a man of 54 with a long history of weight loss, diarrhoea and abdominal pain (see barium enema, Fig. 28.10). There are three ‘skip lesions’ typical of Crohn’s disease, in the ascending colon, the transverse colon and the hepatic flexure showing thickening of the wall, cobblestone mucosal surface and narrowing of the lumen

Granulomas containing multinucleate giant cells (see Fig. 28.6) are usually scattered throughout the inflamed bowel wall as well as in local lymph nodes. (Although these non-caseating granulomas are typical of Crohn’s disease, they are not always found, and ruptured crypt abscesses in ulcerative colitis may also cause them.) Longstanding inflammation leads to progressive fibrosis of the thickened bowel wall, which encroaches on the lumen, producing elongated strictures.

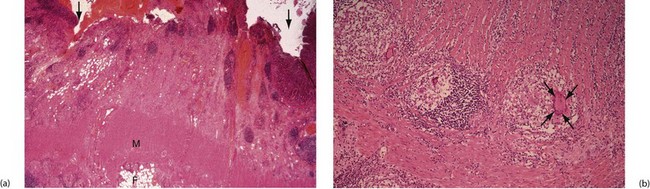

Fig. 28.6 Crohn’s disease affecting the colon—histopathology

(a) Inflammation has produced fissure ulcers (arrowed) which extend into the muscle wall M. Lymphoid aggregates are also present and the inflammatory process extends into serosal fat F.

(b) High-power view showing well-formed granulomas with typical giant cells (arrowed), enabling a confident diagnosis of Crohn’s disease to be made

Effects of mucosal inflammation: Mucosal inflammation causes diarrhoea which, if the colon is involved, may be streaked with mucus and blood. Luminal narrowing in the small bowel results in partial obstruction that causes grumbling, colicky abdominal pain, sometimes with acute episodes. Pain is a prominent feature in Crohn’s disease in contrast to ulcerative colitis, since inflamed large bowel does not obstruct in this way.

Effects of transmural inflammation: Crohn’s disease causes added problems if serosal inflammation extends to adjacent structures. If inflamed bowel impinges on parietal peritoneum, pain becomes localised and more severe and signs of local peritonitis develop. Indeed, Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum may mimic acute appendicitis. At appendicectomy, the terminal ileum is visibly inflamed and the bowel wall abnormally thick to palpation. In this case, the terminal ileum should not be excised as a firm diagnosis of Crohn’s disease requires histological and microbacterial exclusion of Yersinia ileitis as well as tuberculosis. Both may simulate Crohn’s, but are completely reversible with medical treatment.

• Adhesions. These tough, fibrotic post-inflammatory adhesions are rarely symptomatic but constitute a formidable obstacle if operation is needed later

• Perforation. Free perforation is rare but a contained perforation may occur which causes localised pericolic or pelvic abscess formation

• Fistulae. These may develop between diseased bowel and other hollow viscera causing unusual clinical phenomena. For example, a gastro-colic fistula may result in true faecal vomiting; an ileo-rectal fistula may aggravate diarrhoea. Entero-vesical fistulae cause severe urinary tract infections and pneumaturia (passage of urine containing air bubbles), and fistulae between bowel and uterus or vagina lead to vaginal passage of faeces. Entero-cutaneous fistulae between bowel and skin occasionally develop as a complication of bowel resection for Crohn’s disease, or spontaneously

Perianal inflammation: Perianal inflammation occurs in 15% of patients with Crohn’s disease. Symptoms include recurrent perianal abscesses, characteristic blueish, boggy ‘piles’ (see Fig. 28.7) and anterolateral anal fissures. The last two are quite distinct from ordinary haemorrhoids and posterior anal fissures. Multiple fistulae commonly develop between rectum and perianal skin and can extend into the labia or scrotum. Fistulae are sometimes so numerous as to cause a ‘pepper-pot’ or ‘watering-can’ perineum (see Fig. 28.8). Paradoxically, this is more often associated with small bowel disease than colorectal disease.

Systemic features: Like ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease is a systemic disorder and has a similar range of non-GI manifestations (see Box 28.1, p. 367). In contrast with ulcerative colitis, it is usual for patients to feel generally ill during an acute attack. Specific systemic features affecting skin, joints or the eye are relatively uncommon and not necessarily related to bowel disease activity.

Symptoms and signs in crohn’s disease

Symptoms of Crohn’s disease can be similar to those of ulcerative colitis, particularly when large bowel is involved (see Table 28.1, p. 365). Diarrhoea is usually less distressing and less likely to contain blood. Other characteristic symptoms include cramp-like abdominal pain, weight loss and general malaise. As an aide memoire, think of pain, weight loss and diarrhoea as symptomatic of Crohn’s.

Approach to investigation of suspected crohn’s disease

Colonoscopy enables a histological diagnosis to be obtained in colonic disease, and also allows biopsies of terminal ileum to be taken, which are often diagnostic. Barium ‘follow-through’ is the traditional method of examining small bowel but better images are sometimes obtained by controlled instillation of barium into the duodenum via a nasogastric tube. Typical radiological appearances of Crohn’s disease include narrowing of the lumen due to mural oedema and fibrosis, nodularity and cobblestoning of the mucosal surface, deep fissured ulceration extending into the muscular wall, spiky ‘rose thorn’ ulcers and possibly evidence of fistula formation. Radiological changes in small and large bowel are shown in Figures 28.9 and 28.10. Note that large bowel abnormalities on barium enema may be difficult or impossible to distinguish from ulcerative colitis.

Management of Crohn’s disease

• 5-ASA compounds, as used in ulcerative colitis. These act locally, making it a challenge to deliver oral medication to inflamed small bowel without gastric inactivation. Sulfasalazine (a combination of 5-ASA and a carrier, sulfapyridine) is useful in ulcerative colitis and large bowel Crohn’s disease because the active ingredient is released by colonic bacteria. However, some patients suffer side-effects related to the sulfapyridine. Mesalazine is useful for more proximal Crohn’s disease as the active compound is released earlier. Rectal Crohn’s disease can be treated with 5-ASA suppositories or enemas, as in ulcerative colitis. 5-ASA compounds can be used as maintenance therapy in Crohn’s disease but large doses are required

• Corticosteroids can act as systemic agents (e.g. prednisolone) or locally. Budesonide is a new oral steroid which is mostly released in the terminal ileum then rapidly inactivated by the liver after absorption, minimising systemic effects. Corticosteroids act rapidly to control flare-ups, but are rarely used for long-term maintenance

• Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine are immunosuppressants, sometimes used in more severe Crohn’s disease. They can spare the need for damaging steroids, or they can help maintain remission in patients who relapse on 5-ASA compounds. About 10% of those treated are at risk of bone marrow suppression but those at risk can be predicted by pre-treatment testing

• Methotrexate acts both as an anti-inflammatory agent and an immunomodulator but has potentially serious side-effects upon liver and bone marrow

• Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody to TNFα, an inflammatory mediator. It is given by intravenous infusion for acute disease and is usually effective within 2 weeks. The drug can be given at 8-weekly intervals to maintain remission. Risks include developing antibodies to the drug. It should not be used where there is active infection or an abscess

The role of surgery in Crohn’s disease

The main indications for surgery can be summarised as follows:

• Acute complications, e.g. abscess, perforation

• Persistent local ileal disease

• Intolerable long-term obstructive and other symptoms, e.g. abdominal pain, perianal disease, general ill-health

• Entero-cutaneous fistulae and symptomatic internal fistulae

The choice of operation depends on the site and extent of disease. The former belief that all disease must be resected has been abandoned. Given the diffuse nature of the disease and likelihood of further operations, as much bowel as possible should be preserved. Surgery for multiple small bowel strictures now involves stricturoplasty of each lesion, a technique of enlarging the lumen of diseased bowel without losing potential absorptive length. If disease is limited, resection of the diseased segment with a small margin of normal tissue may be performed, followed by wide side-to-side anastomosis. Abscesses are usually treated by simple drainage, with resection of the affected bowel at the same time or later.

Other Chronic Inflammations of the Colon

Clinical features of amoebic colitis: The disease usually affects the proximal colon, causing colicky abdominal pain, erratic bowel habit with episodes of blood-stained loose stools and right iliac fossa tenderness. If the distal colon is involved, the patient suffers chronic watery diarrhoea with blood and mucus. When the entire colon is involved, there is generalised abdominal tenderness as well as systemic features, e.g. pyrexia and progressive weight loss. Large granulomatous colonic lesions known as amoebomas may be palpable and must be differentiated from carcinoma or diverticular disease.

Diagnosis of amoebiasis: In developed countries, amoebic colitis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s colitis. Amoebic colitis is best diagnosed by microscopic examination of fresh stool specimens; this may reveal trophozoites containing ingested red cells.

Treatment of amoebiasis: Metronidazole is the drug treatment of choice for amoebic dysentery and is given orally, 800 mg three times daily for 5 days, followed by diloxanide 500 mg three times daily for 10 days to eradicate cysts. Liver abscesses are treated with metronidazole 400 mg three times daily for 5–10 days followed again by diloxanide. Emergency surgery is occasionally necessary in fulminating amoebic colitis or less urgently for large liver abscesses.