Chapter 39 Chronic Illness in Childhood

Epidemiology

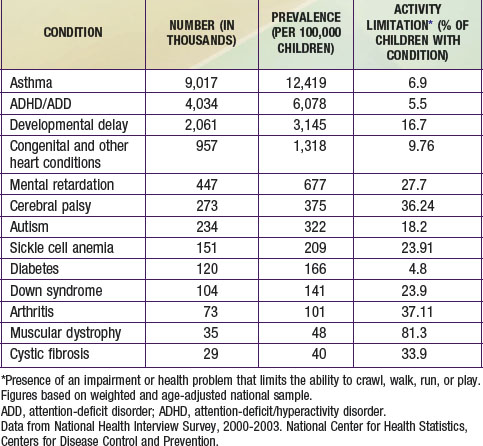

National survey data suggest that 30% of all children have some form of chronic health condition (Table 39-1). If allergies, eczema, minor visual impairments, and other conditions not likely to generate serious consequences are excluded, then between 15% and 20% of all children have a chronic physical, learning, or developmental disorder. Boys have higher rates of chronic illness than do girls. There is considerable variation in the nature and severity of chronic illnesses in children (Table 39-2). The most common serious chronic condition is asthma, with 12% of children having received a diagnosis of asthma at some time in their lives; half of these children were reported to have experienced asthma symptoms in the prior 12 mo (Chapter 138). Mental health and behavioral conditions represent a large and growing number of children with chronic illness. It has been estimated that almost 21% of U.S. children between 9 and 17 yr of age have a diagnosable mental or addictive disorder associated with some impairment; approximately 11% had significant impairment. Estimates suggest that 5% had major depression (Chapter 23) and approximately 6% have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Chapter 30). Overweight is not usually defined as a chronic health condition; however, in 2008 12% of 2-5 yr olds, 17% of 6-11 yr olds, and nearly 18% of all children aged 12 through 19 yr have a body mass index above the 95th percentile (Chapter 44). Co-morbid conditions such as hypertension and a variety of metabolic disorders may exist.

Table 39-1 PREVALENCE AND ACTIVITY LIMITATION FOR SELECTED CHRONIC DISEASES IN CHILDREN <18 YEARS OF AGE: UNITED STATES, 2000-2003

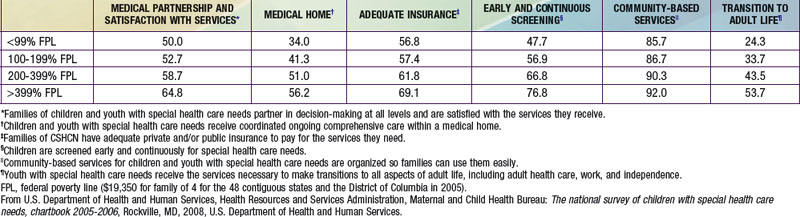

Table 39-2 QUALITY MEASURES FOR HEALTH CARE RECEIVED BY CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL HEALTH CARE NEEDS (CSHCN) BY FAMILY INCOME: UNITED STATES, 2005-2006 (PERCENT MEETING QUALITY MEASURE)

These current prevalence figures represent a substantial increase in childhood chronic illness in the past several decades. While approximately 9% of children were reported to have a chronic health condition that limited their activities in 2005, the comparable figure in 1960 was only 2%. Although the increase in childhood chronic illness is likely due in part to changes in survey methodologies, improvements in diagnosis, and expanded public awareness of behavioral and developmental disorders, there is strong evidence that the prevalence of certain important chronic child health conditions has increased. Asthma rates rose from <4% in 1980 to 9% in 2007, with the highest rates among the poorest children. The prevalence of ADHD (Chapter 30) and autism (Chapter 28) has also increased considerably. Although improvements in the survival of infants and young children from prematurity, congenital anomalies, and genetic disorders have also contributed to the rising prevalence rates, this source accounts for only a small portion of all chronic illness in childhood.

Enhanced Needs of Children with Chronic Illness and Their Families

Complex Clinical Management

Pain

Many seriously ill children suffer from chronic pain (rheumatoid arthritis, spastic cerebral palsy [CP]), recurrent pain during exacerbations of underlying disease (inflammatory bowel diseases, sickle cell anemia), or acute pain related to procedures, surgeries, or diagnostic tests. This pain can alter a child’s affect and influence their academic and social development, while also decreasing the family’s quality of life (Chapter 71). Assessing pain in young children or those with developmental disorders can be difficult and should always consider sociocultural and psychologic factors as well as developmental stage. Because serious, chronic pain is relatively unusual in children, its management may require the involvement of pediatric pain subspecialists who may practice with multidisciplinary teams in regional centers. The emotional toll on parents of children experiencing chronic pain can also be profound and require close attention by medical personnel.

Comprehensive Care and the Medical Home

All children require a clinician who takes responsibility for their comprehensive health care needs. To meet this responsibility, the coordinated implementation of a series of essential practice components, often termed the medical home, is recommended. These services should be provided within a broader system of care that emphasizes partnering in decision-making between the family and medical providers, coordination of services among medical and community service providers, adequate health insurance coverage, ongoing screening for special health care needs, critical educational and community-based services, and special attention to the needs of older children as they transition to adult life and health care systems. Evidence suggests that the extent to which these care requirements are being met for families with children with special health care needs is highly variable (see Table 39-1). Though essential for all children, these practice elements take on special importance for children with chronic disorders and are outlined as follows.

Continuity of Care

Children with chronic illnesses are particularly dependent on a stable, ongoing relationship with clinicians and the health care system. The duration and complexity of chronic illness in children require that the clinician responsible for coordinating the child’s care have a good understanding of the child’s clinical history, including patterns of exacerbation and response to medications and other interventions. Continuity of care also serves as a basis for building trust and effective communication between affected families and clinicians, a prerequisite for high-quality care. Practice structures, therefore, should ensure the identification of a principal clinical provider and facilitate the provider’s involvement in all necessary care. Transitioning of care as the child reaches adulthood requires planning and coordination and recognition of the emotional bonds that likely have developed between the child (and his or her family) and the practitioner, which now must be transferred to another provider (Chapter 106.4).

American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Children with Disabilities. Care coordination in the medical home: integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1238-1244.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities. The role of the pediatrician in transitioning children and adolescents with developmental disabilities and chronic illnesses from school to work or college. Pediatrics. 2000;106:854-856.

Bethell CD, Read D, Blumberg SJ, et al. What is the prevalence of children with special health care needs? Toward an understanding of variations in findings and methods across three national surveys. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12:1-14.

Gordon JB, Colby HH, Bartelt T, et al. A tertiary care–primary care partnership model for medically complex and fragile children and youth with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:937-944.

Homer CJ, Klatka K, Romm D, et al. A review of the evidence for the medical home for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e922-e937.

Kastner TA, American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Children with Disabilities. Managed care and children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1693-1698.

Newacheck PW, Kim SE. A national profile of health care utilization and expenditures for children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:10-17.

Palfrey JS, Sofis LA, Davidson EJ, et al. The pediatric alliance of coordinated care: evaluation of a medical home model. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1507-1516.

Perrin JM, Bloom SR, Gortmaker SL. The increase of childhood chronic conditions in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:2755-2759.

Stein REK, editor. Caring for children with chronic illness. New York: Springer, 1989.

Strickland B, McPherson M, Weissman G, et al. Access to the medical home: results of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1485-1492.

Van Cleave J, Davis MM. Preventive care utilization among children with and without special health care needs: associations with unmet need. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8:305-311.

Wise PH. The transformation of child health in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23:9-25.