Chapter 10 CHRONIC COUGH

General Discussion

The 1998 American College of Chest Physicians guidelines advocate that “the approach to managing chronic cough in children is similar to the approach in adults.” However, a subsequent study found that protracted bacterial bronchitis was the most common diagnosis in children, in contrast to adults, in whom asthma, postnasal drip syndrome, and GERD are the most common diagnoses. In fact, these adult diagnoses were found to be relatively uncommon in children. Because some controversy exists regarding the best algorithmic approach to the child with chronic cough, we provide two algorithms (Figures 10-1 and 10-2). The history and physical examination should provide significant guidance when using these algorithms. At some points in the algorithms, an empiric trial of therapy may be considered before additional testing is performed.

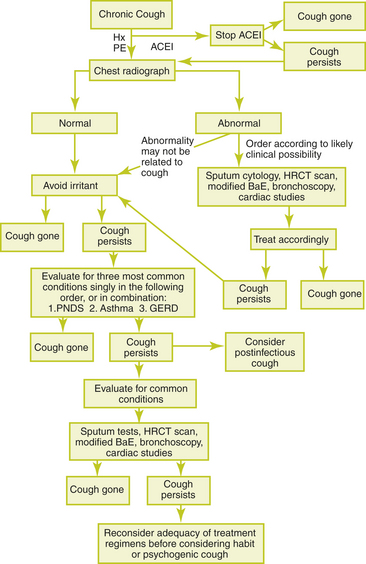

Figure 10-1 Sequential approach to the evaluation of chronic cough in the immunocompetent adult.

(From Irwin RS, et al. Managing cough as a defense mechanism and as a symptom: a consensus panel report of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest 1998;114(2 suppl managing):166S

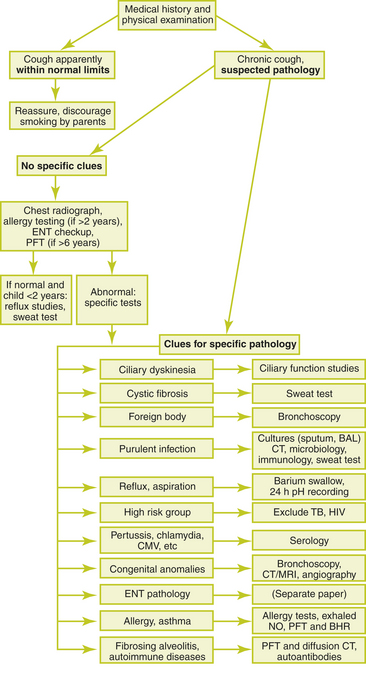

Figure 10-2 Diagnostic algorithm for use in children with chronic cough.

(From de Jongste JC, Shields MD. Chronic cough in children. Thorax 2003;58:998–1003, with permission.)

1. Neonatal onset of the cough, which may represent a congenital defect, a problem with ciliary function (such as cystic fibrosis or primary cilial abnormality), an anatomic lesion in the airways, or a chronic viral pneumonia acquired in utero or during the perinatal period

2. Chronic moist or purulent cough

3. Cough that began and persisted after a choking episode, which may be the result of foreign body aspiration

4. Cough that occurs during or after feeding, which suggests gastroesophageal reflux or aspiration during feeding

Causes of Chronic Cough

Key Historical Features

Severity and time course of the cough

Severity and time course of the cough

Relationship of cough to meals

Relationship of cough to meals

Relationship of cough to exercise

Relationship of cough to exercise

Possibility of foreign body aspiration

Possibility of foreign body aspiration

Symptoms of asthma or known asthma triggers

Symptoms of asthma or known asthma triggers

Symptoms of postnasal drip (throat clearing, nasal discharge, excessive phlegm production)

Symptoms of postnasal drip (throat clearing, nasal discharge, excessive phlegm production)

Risk of contact with tuberculosis or HIV

Risk of contact with tuberculosis or HIV

Key Physical Findings

Height and weight measurements

Height and weight measurements

Head and neck examination for lymphadenopathy, evidence of allergies, sinus infection, foreign body, or poor dental hygiene

Head and neck examination for lymphadenopathy, evidence of allergies, sinus infection, foreign body, or poor dental hygiene

Cardiac examination for evidence of left ventricular failure

Cardiac examination for evidence of left ventricular failure

Pulmonary examination for any abnormal breath sounds

Pulmonary examination for any abnormal breath sounds

Chest examination for a barrel-shaped chest

Chest examination for a barrel-shaped chest

Suggested Work-up

| Chest radiographs | To evaluate for infiltrates, atelectasis, congenital abnormalities, radio-opaque foreign bodies, or cardiomegaly |

| Complete blood cell count (CBC) | To evaluate for infection or eosinophilia |

| Purified protein derivative (PPD) | To evaluate for tuberculosis, especially if risk factors for exposure are present |

Additional Work-up

| High-resolution chest CT | May reveal bronchiectasis that is not seen on plain radiography |

| Sputum gram stain, cultures, and serology (e.g., Bordetella pertussis, Chlamydia spp., cytomegalovirus) | To evaluate for infection, especially if there are fevers or purulent sputum |

| Adenosine 5’-monophosphate bronchial challenge | To differentiate asthma from other chronic pulmonary diseases of childhood |

| Immunoglobulins and subclasses | To evaluate for immunologic disease |

| Pulmonary function tests | To evaluate for reversible obstruction |

| Bronchoscopy | If there is suspicion of foreign-body aspiration or congenital anomalies. Also may provide specimens from the lower airways for culture and microscopy. |

| Barium swallow with 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring | If reflux is suspected. Alternatively, an empiric trial of therapy may be considered. |

| Sinus radiographs or computed tomography (CT) scan | If sinusitis is suspected. Alternatively, an empiric trial of therapy may be considered. |

| Chloride sweat test | Should be performed in children with chronic cough and failure to thrive and in any child with a chronic productive cough to evaluate for cystic fibrosis |

| Ciliary function studies | Performed at specialized centers to evaluate for primary ciliary dyskinesia |

| HIV test | If risk factors for HIV exposure are present |

1. Archer L.N.J., Simpson H. Night cough counts and diary card scores in asthma. Arch Dis Child. 1998;60:473–474.

2. de Jongste J.C., Shields M.D. Chronic cough in children. Thorax. 2003;58:998–1003.

3. Falconer A., Oldman C., Helms P. Poor agreement between reported and recorded nocturnal cough in asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1993;15:209–211.

4. Holmes R.L., Fadded C.T. Evaluation of the patient with chronic cough. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:2159–2166.

5. Irwin R.S., et al. Managing cough as a defense mechanism and as a symptom: a consensus panel report of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 1998;114(2 suppl managing):166S.

6. Kamei R.K. Chronic cough in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1991;38:593–605.

7. Marchant J.M., et al. Evaluation and outcome of young children with chronic cough. Chest. 2006;129:1132–1141.

8. Munyard P., Bush A. How much coughing is normal? Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:531–534.