43 Chronic and Cancer Pain Care

An Introduction and Perspective

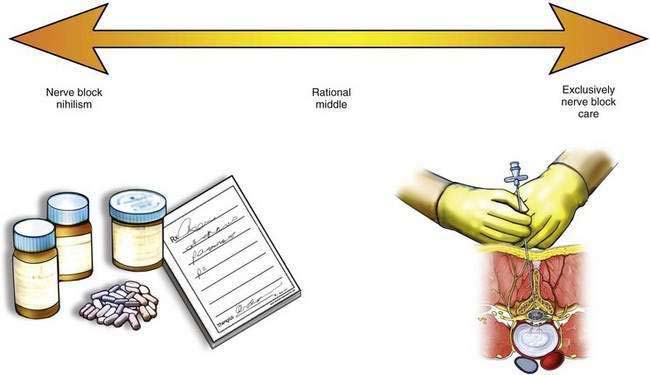

Many have considered short-term approaches to pain care as the ideal, using nerve blocks to the exclusion of other therapies. Other colleagues have vigorously and actively avoided any use of regional analgesia techniques in the patient with chronic pain or cancer pain. As a physician with a practice of pain medicine spanning nearly three decades, I believe that the polar ends of this conceptual continuum (Fig. 43-1) represent incomplete and inappropriate approaches to pain medicine. Over the long years of my practice treating a wide selection of patients, increasingly fewer of my patients receive recommendations for an exclusive regional analgesic/anesthetic approach to their pain control or rehabilitation regimen. In fact, many of my patients receive oral analgesia options with a physical rehabilitation and activity regimen, without any regional techniques as part of their therapy. These practices do not suggest that regional analgesic/anesthetic/neuromodulation regimens are not indicated in our patients. In fact, they are indicated in many patients, but they should be used with a clear indication for how they help in diagnosis or in the pain control and rehabilitation regimen in the patient with chronic pain. Their use should be incorporated into a chronic rehabilitation and cancer pain control regimen that focuses on return of function, always keeping in mind our charge as physicians to balance risk and benefit for each individual patient.