Chapter 193 Cholera

Epidemiology

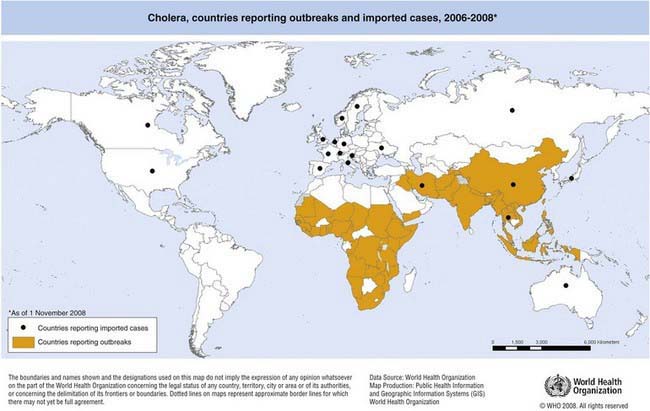

The first 6 cholera pandemics originated in the Indian subcontinent and were caused by classical O1 V. cholerae. The seventh pandemic is the most extensive of all and is caused by V. cholerae O1 El Tor. It began in 1961 in Sulawesi, Indonesia, and has spread to the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, Africa, Oceania, Southern Europe, and the Americas. In 1991, V. cholerae O1 El Tor first appeared in Peru before rapidly spreading in the Americas. Cholera becomes endemic in areas following outbreaks when a large segment of the population develops immunity to the disease after recurrent exposure. The disease is now endemic in parts of East, Southern, and Northwest Africa, as well as in South and Southeast Asia (Fig. 193-1).

Clinical Manifestations

Cholera gravis, the most severe form of the disease, results when purging rates of 500-1000 mL/hr occur. This purging leads to dehydration manifested by decreased urine output, sunken fontanels (in infants), sunken eyes, absence of tears, dry oral mucosa, shriveled hands and feet (washerwoman’s hands), poor skin turgor, thready pulse, tachycardia, hypotension, and vascular collapse (Fig. 193-2). Patients with metabolic acidosis can present with typical Kussmaul breathing. Although patients may be initially thirsty and awake, they rapidly progress to obtundation and coma. If fluid losses are not rapidly corrected, death can occur within hours.

Treatment

Rehydration is the mainstay of therapy (Chapter 332). Effective and timely case management considerably decreases mortality. Children with mild or moderate dehydration may be treated with oral rehydration solution (ORS) unless the patient is in shock, is obtunded, or has intestinal ileus. Vomiting is not a contraindication to ORS. Severely dehydrated patients require intravenous fluid, ideally with lactated Ringer solution. When available, rice-based ORS should be used during rehydration, because this fluid has been shown to be superior to standard ORS in children and adults with cholera. Close monitoring is necessary, especially during the first 24 hr of illness, when large amounts of stool may be passed. After rehydration, patients have to be reassessed every 1-2 hr, or more frequently if profuse diarrhea is ongoing. Feeding should not be withheld during diarrhea. Frequent, small feedings are better tolerated than less frequent, large feedings.

As soon as vomiting stops (usually within 4-6 hr after initiation of rehydration therapy), an antibiotic to which local V. cholerae strains are sensitive must be administered. Antibiotics (Table 193-1) shorten the duration of illness, decrease fecal excretion of vibrios, decrease the volume of diarrhea, and reduce the fluid requirement during rehydration. Single-dose doxycycline increases compliance; there have been increasing reports of resistance to tetracyclines. Ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are also effective against cholera. Cephalosporins and aminoglycosides are not clinically effective against cholera and therefore should not be used, even if in vitro tests show strains to be sensitive.

Table 193-1 SUGGESTED ANTIMICROBIALS FOR SUSPECTED CHOLERA CASES WITH SEVERE DEHYDRATION

| ANTIBIOTIC OF CHOICE* | ALTERNATIVE |

|---|---|

| Doxycycline (adults and older children): 300 mg given as a single dose or Tetracycline 12.5 mg/kg/dose 4 times/day × 3 days (up to 500 mg per dose × 3 days) |

Erythromycin 12.5 mg/kg/dose 4 times a day × 3 days (up to 250 mg 4 times a day × 3 days) |

* Selection of an antimicrobial should be based on sensitivity patterns of strains of Vibrio cholerae O1 or O139 in the area.

Adapted from World Health Organization: The treatment of diarrhea: a manual for physicians and other senior health workers—4th revision, Geneva, 2005, World Health Organization.

Prevention

No country or territory requires vaccination against cholera as a condition for entry. There is no cholera vaccine licensed in the USA. An internationally licensed killed whole-cell oral cholera vaccine with recombinant B subunit (Dukoral, SBL/Crucell) has been available in more than 60 countries, including the European Union, and provides protection against cholera in endemic areas as well as cross-protection against certain strains of enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC). Older-generation parenteral cholera vaccines have not been recommended by WHO, due to the limited protection they confer and their high reactogenicity. Oral cholera vaccines (OCVs) have been available for >2 decades and are mostly used by travelers from industrialized countries going to cholera-affected areas. Although WHO has recommended the use of OCV in the control of cholera in certain endemic and epidemic situations since 2001, these vaccines have not been extensively adopted. Table 193-2 shows currently licensed vaccines and dosing schedules. Live-attenuated oral cholera vaccine (Orochol, Berna Biotech/Crucell) has not been shown to be protective against cholera in a clinical trial in an endemic area and is no longer manufactured.

| VACCINE TRADE NAME | CONTENTS | DOSING SCHEDULE FOR CHOLERA |

|---|---|---|

| Dukoral (SBL/Crucell) |

Chaignat CL, Monti V. Use of oral cholera vaccine in complex emergencies: what next? Summary report of an expert meeting and recommendations of WHO. J Health Popul Nutr. 2007;25:244-261.

Constantin de Magny G, Murtugudde R, Sapiano MR, et al. Environmental signatures associated with cholera epidemics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17676-17681.

Deen JL, von Seidlein L, Sur D, et al. The high burden of cholera in children: comparison of incidence from endemic areas in Asia and Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e173.

Faruque AS, Alam K, Malek MA, et al. Emergence of multidrug-resistant strain of Vibrio cholerae O1 in Bangladesh and reversal of their susceptibility to tetracycline after two years. J Health Popul Nutr. 2007;25:241-243.

Griffith DC, Kelly-Hope LA, Miller MA. Review of reported cholera outbreaks worldwide, 1995–2005. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:973-977.

Harris JB, LaRocque RC, Charles RC, et al. Cholera’s western front. Lancet. 2010;376:1961-1964.

Kumar P, Jain M, Goel AK, et al. A large cholera outbreak due to a new cholera toxin variant of the Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor biotype in Orissa, Eastern India. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58(Pt 2):234-238.

Lopez AL, Clemens JD, Deen J, Jodar L. Cholera vaccines for the developing world. Hum Vaccin. 2008;4:165-169.

Nelson EJ, Nelson DS, Salam MA, et al. Antibiotics for both moderate and severe cholera. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(1):5-9.

World Health Organization. Cholera, 2007. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2008;83:269-283.

World Health Organization. The treatment of diarrhea: a manual for physicians and other senior health workers—4th revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

Zuckerman JN, Rombo L, Fisch A. The true burden and risk of cholera: implications for prevention and control. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:521-530.