5 Children and adolescents

History

The history (Box 5.1) will normally be taken from the accompanying carer, but an older child can be invited to give his version of events first. It is appropriate to give an adolescent the opportunity for a few minutes of confidential time during the consultation. Use this to ask questions about alcohol, drugs and sexual activity which he may be uncomfortable discussing in front of his parents. Even younger children should be asked simple things in words they can understand. Involve them by asking relevant points such as the site of the pain, etc. Remember that the carer is giving their version of the problem, not the child’s. Parents may also welcome an opportunity to talk in private away from the child, and it is often during such discussion that the real reason for the consultation emerges. Always take notice of what the carer is saying, and listen to their concerns. Any interruptions should be to clarify rather than try and direct the history. Make sure they are given full attention and that they feel their concerns are being taken seriously. All the time they are talking, keep watching everything that the child is doing and their reactions.

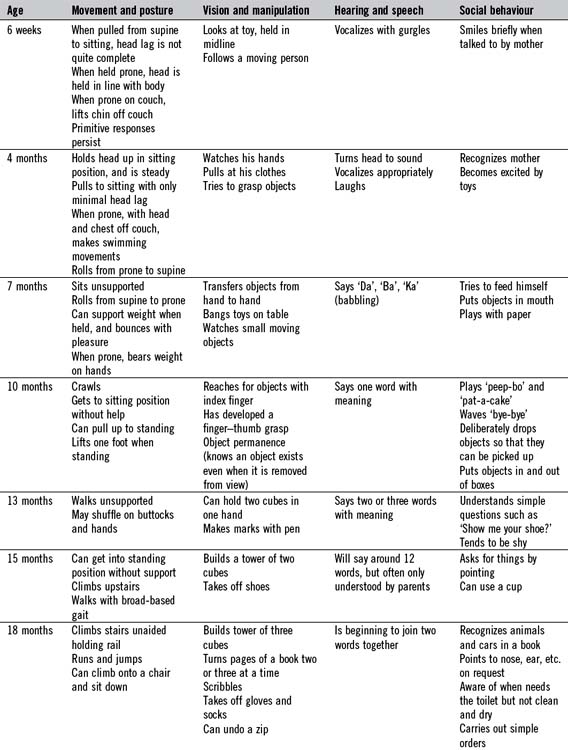

In children, the previous medical history starts from birth and specific attention should be paid to the pregnancy and newborn period (Box 5.2). Is the child fully immunized? This can be checked in the parent-held ‘red book’ or child health record, which should have documentation of child health clinic attendances, weights, immunizations, etc. Enquire particularly as to the nature and severity of previous illnesses and the age at which they occurred, for example common childhood infections such as chickenpox, admissions to hospital and, in particular, to intensive care, significant injuries and accidents. Is the child taking any regular medication and is he allergic to anything? It is important to ask about the child’s developmental progress: when did the child first sit up, smile, crawl, walk and talk? Fuller details regarding the ‘milestones of development’ are given in Table 5.1. Some useful general questions are outlined in Box 5.3.

Box 5.2 Pregnancy and infancy

Did the mother have any particular illnesses or infections, or was she taking any drugs during the pregnancy (including alcohol)?

Did the mother have any particular illnesses or infections, or was she taking any drugs during the pregnancy (including alcohol)?

What were the birth weight and type of delivery?

What were the birth weight and type of delivery?

Were there any problems in the newborn period: jaundice, breathing problems, fits, feeding difficulties?

Were there any problems in the newborn period: jaundice, breathing problems, fits, feeding difficulties?

Has the baby had any illnesses?

Has the baby had any illnesses?

How was the baby fed? When were solid foods introduced?

How was the baby fed? When were solid foods introduced?

Were there any intolerances to food?

Were there any intolerances to food?

Box 5.3 General questions

What are the child’s present habits with regard to eating, sleeping, bowels and micturition?

What are the child’s present habits with regard to eating, sleeping, bowels and micturition?

What sort of personality does he have – e.g. extrovert, moody?

What sort of personality does he have – e.g. extrovert, moody?

Behaviour: anything unusual which the parent is worried about?

Behaviour: anything unusual which the parent is worried about?

How does he get on with other children?

How does he get on with other children?

How does the child compare with siblings or friends of the same age?

How does the child compare with siblings or friends of the same age?

School: which school, does he like it, academic achievement, does he miss much school?

School: which school, does he like it, academic achievement, does he miss much school?

Family history

How old are the parents? Are they consanguineous?

How old are the parents? Are they consanguineous?

How many children are there in the family? What are their ages and sex?

How many children are there in the family? What are their ages and sex?

Who else lives in the family home?

Who else lives in the family home?

Have there been any stillbirths, miscarriages or other childhood deaths in the family?

Have there been any stillbirths, miscarriages or other childhood deaths in the family?

Are there any illnesses in the siblings, parents or any near relatives?

Are there any illnesses in the siblings, parents or any near relatives?

Examination

A key principle in the examination of children is that most of the information needed to make a diagnosis will be gleaned from careful observation, including listening to the child and playing with him. Findings can then be consolidated with the remaining techniques requiring laying on of hands. Older children will usually cooperate sufficiently to be examined lying down, and routine physical examination is similar to an adult examination. A younger child should be examined sitting on his carer’s lap, as any attempt to get him to lie down will result in instant distress. Always talk to children however young; do not be afraid of looking silly if the result is a cooperative child. Those parts of the examination that are painful or unpleasant should be left until last: if an attempt is made to examine a child’s throat at the outset, the immediate response will be crying. Offer the child something to play with – even a stethoscope will be a source of amusement to a young infant. Children often find it amusing if their toy is examined first. The scheme set out in Box 5.4 can be adapted opportunistically, provided all areas are covered.

The head, face and neck

Look at the child’s face and ask the following questions:

Does it look normal? If not, try to identify which features seem unusual. There are many hundreds of syndromes diagnosable by the facial appearance, and the salient features should be carefully noted.

Does it look normal? If not, try to identify which features seem unusual. There are many hundreds of syndromes diagnosable by the facial appearance, and the salient features should be carefully noted.

If the baby looks dysmorphic, then do not forget to look at the parents. It may then be obvious that what seems abnormal may be nothing more than a family trait. If the appearance is still not too clear, ask who the baby looks like.

If the baby looks dysmorphic, then do not forget to look at the parents. It may then be obvious that what seems abnormal may be nothing more than a family trait. If the appearance is still not too clear, ask who the baby looks like.

Does the child have a large or protruding tongue?

Does the child have a large or protruding tongue?

Are the ears in the normal position, or are they low set and abnormal in any way?

Are the ears in the normal position, or are they low set and abnormal in any way?

Are the eyes small (microphthalmus)? Are they set close together or wide apart (hypo- or hypertelorism)?

Are the eyes small (microphthalmus)? Are they set close together or wide apart (hypo- or hypertelorism)?

Next note the shape of the head. This needs to be done by viewing the child’s head from the front, sides and from above. It may be small if the baby is microcephalic, globular if the baby is hydrocephalic, sometimes with dilated veins over the skin surface, or brachycephalic (flattened over the occiput), for example in trisomy 21. It is often asymmetrical (plagiocephalic) in normal infants who tend to lie with their heads persistently on one side (Fig. 5.1). This is now much more common because babies are placed on their backs to sleep in order to reduce the risk of sudden death in infancy. It becomes much less noticeable as the child grows older.

The abdomen

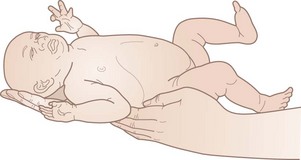

The abdomen can be a little difficult to examine if the baby is crying, which is why it is important to have gained the child’s cooperation by this point in the examination. Most infants and toddlers will need to be examined while sitting on their carer’s lap (Fig. 5.2). It is sometimes possible to quieten a crying infant by placing him over his mother’s shoulder and examining him from behind. Small infants can be given a feed to quieten them. Older children can be asked if they would be happy to lie on an examination couch.

The examination needs to be structured along the three essential components of looking (observation), feeling (palpation) and listening (auscultation). During the first 3 years of life, the abdomen often gives an impression of being protuberant due to the laxity of the rectus muscles. Causes of true abdominal distension are shown in Box 5.5. Look for any obvious distension or for peristaltic waves suggesting intestinal obstruction. Note the umbilicus, and whether or not there is a hernia. Palpation should be gentle and light. Always ask the child if his tummy hurts anywhere and watch his facial expression during palpation. The liver edge can be felt in normal children up to the age of 4 years; it can be anything up to 2 cm below the costal margin. When enlarged, the spleen may be felt below the left costal margin, and in infancy it is more anterior and superficial than in the older child or adult. Slight enlargement of the spleen can occur in many childhood infections. Causes of hepatosplenomegaly are listed in Table 5.2. Faecal masses can be felt in the left iliac fossa in constipated children. They often feel like a sausage which can be rolled underneath the finger tips. A full or distended bladder presents as a mass arising from the pelvis. Deep palpation of the kidneys can be carried out last. Although it would be logical to examine the groin area at this time, it is often better to do this at a later stage. If the child has cried persistently, it is still possible to examine the abdomen. When the baby breathes in and the abdominal muscles relax, the abdominal viscera and other masses, if present, can be palpated.

Table 5.2 Causes of hepatomegaly and splenomegaly in children

| Hepatomegaly | Splenomegaly | Hepatosplenomegaly |

|---|---|---|

The chest

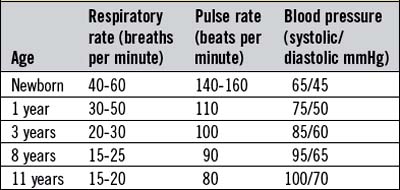

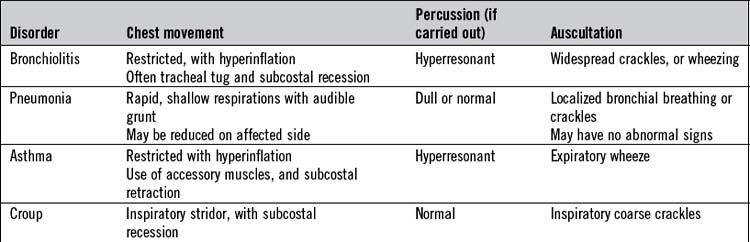

Examining the chest in a child takes in both the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. The basic structure remains the same, at first looking then feeling then listening with the stethoscope. It helps to have let the child play with the stethoscope at an earlier stage of the examination to alleviate any worries about this strange instrument. Observation will give much of the information required for the diagnosis, particularly in younger children and infants. On observation, check for abnormalities which are fixed and those which become obvious on movement. Static deformities in children include pectus excavatum and carinatum which are a source of great anxiety to many parents, but are not usually of any clinical importance. Fixed indentation of the lower ribs at the line of insertion of the diaphragm (Harrison’s sulcus) may be seen in obstructive airway disease, due either to asthma or to a nasopharynx blocked by adenoidal hypertrophy or in conditions leading to increased pulmonary blood flow. Look from the side for an increased anteroposterior diameter of the chest, which could be a sign of a chronic lung disease such as cystic fibrosis. Thickening of the costochondral junction is felt in rickets (rachitic rosary). Note any scars as a result of cardiac surgery. It is important to look for the thoracotomy scar under the arms or even round the back, otherwise you will miss it (Box 5.6). Sternotomy scars usually indicate the child has had major heart surgery involving valves or closure of septal defects. Asymmetry of the chest becomes more obvious on movement (dynamic deformity) and may indicate an underlying pneumothorax or empyema. Look for any increased work of breathing. This may be indicated by seeing recession (intercostal or subcostal), tracheal tug or flaring of the nares when breathing or use of accessory muscles. Count the respiratory rate (Table 5.3) which, in infants, must be done over a minute to be accurate, due to periodic breathing. Listen for grunting respiration which is audible in infants who are attempting to prevent alveolar collapse by creating their own positive airway pressure. The grunting expiration is followed by inspiration, and then a pause.

A stethoscope with a small bell chest piece is suitable for auscultation of the child’s chest. Do not use adult-sized chest pieces, as it is impossible to localize added sounds accurately with a chest piece covering such a wide area in a small child. Often it is less threatening to examine the back of the chest first, and much more information about the lungs can be acquired in this way. Listen for the breath sounds and adventitious sounds. Because of the thin chest wall, breath sounds are louder in children than in adults, and their character is more like the bronchial breathing of adults (puerile breathing). Upper respiratory tract infections in children often give rise to loud, coarse rhonchi, which are conducted down the trachea and main bronchi (Table 5.4). All is not lost if the child is crying, as this is associated with deep inspiration, and this is the time to listen for the character of the breath sounds.

When you are auscultating the front of the chest, the child’s immediate instinct is to push the stethoscope away. You can ask the parent to hold the child’s hands or try and distract the child with toys held in the hand (Fig. 5.3). It is a good idea to examine a doll or teddy bear first if the child is playing with one. The normal splitting of the first and second sounds is easier to hear in children than in adults. Venous hums and functional systolic flow murmurs are often heard in normal children (Box 5.7). If the murmur does not fit into this classification, remember that most cardiac problems in children are as a result of congenital heart disease and not acquired as in adults (Table 5.5). Count the heart rate in young children (see Table 5.3). Arrythmias are uncommon in children unless they have had cardiac surgery.

Table 5.5 Categories of key congenital heart disease lesions

| Acyanotic (presents with hyperdynamic circulation in heart failure) | Cyanotic (presents with respiratory distress and cyanosis) | Outflow tract obstruction (presents grey and shocked) |

|---|---|---|

| Ventricular septal defect (VSD) (pansystolic murmur at left sternal edge) Atrial septal defect (pulmonary flow murmur with fixed splitting of 2nd heart sound) Persistant ductus arteriosus (continuous ‘machinery’ murmur) |

Pulmonary stenosis (PS) (ejection systolic murmur at the left 2nd intercostal space) Tetralogy of Fallot (murmur of PS ± VSD and right ventricular heave) Transposition of the great arteries (no murmur) |

Coarctation of the aorta (pansystolic murmur at left sternal edge) |

Neurological examination

Getting a child’s limbs into the correct position to test tendon reflexes may take some time. Often they can be elicited by using a finger rather than a patellar hammer. Tendon reflexes in young infants tend to be brisk, and up to 18 months of age the plantar responses are extensor. The persistence of an extensor response beyond the age of 2 years indicates an upper motor neurone lesion. Note whether primitive reflexes have persisted (Box 5.8) indicating significant neurodevelopmental dysfunction.

The eyes

The eyes should now be checked. Inspect them for ptosis, conjunctivitis, cataracts or congenital defects such as colobomata. Watch for spontaneous nystagmus or roaming eye movements which may indicate a visual impairment. It is very important to check for squints, as immediate ophthalmological referral is necessary, however young the infant. Squints are checked for by shining a light in the eyes from in front of the face; the light reflex should be at the same position in each cornea. A cover test should then be used (see Ch. 14), using a doll or some other appropriate toy on which the child can focus his gaze. Pupillary accommodation and light reactions can be noted at the same time. Examination of the fundus is particularly difficult in infants and will require dilatation of the pupils. It should be possible to see the red reflex which, if absent, is suggestive of a corneal, lens or vitreous opacity, such as cataract or retinoblastoma. Usually, enough of the disc can be seen to detect papilloedema. The testing of vision in young children is included in the section on developmental screening examination (see p. 72).

The genitalia, groins and anus

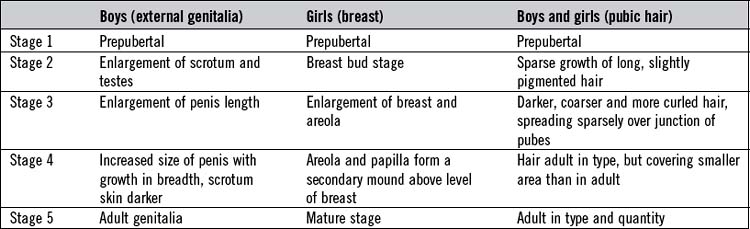

In older children and adolescents, it is important to assess puberty using the Tanner stage (Table 5.6). This will involve examination of the genitalia and looking for breast development and body hair.

The nose, ears, mouth and throat

A cooperative child will allow a look into his ears but, if not, the child should be held by the mother, as shown in Figure 5.4. Held in such a way, the child can be kept still long enough for the eardrums to be inspected. Look carefully for the light reflex, which can be lost if the child has chronic secretory otitis media (‘glue ear’). In acute suppurative otitis media, the drum may be bright red and bulging.

The mouth and throat can be examined by encouraging a cooperative child to ‘show me your teeth’; an open mouth will then allow a clear view of the mouth and fauces. If uncooperative, the child will need to be held as shown in Figure 5.5. Sometimes it is not too disastrous if the child cries at this point, as this will give a very clear view of the teeth, the tonsils and sometimes even the epiglottis. A spatula is a terrifying instrument to the average child, causing most to clamp their teeth shut. If this happens, the spatula should be advanced to the back of the tongue to induce a gag reflex. Look for the presence of the white patches of candida infection, ulcers seen in Crohn’s disease and the Koplik’s spots seen in measles.

Routine measurements

Height and weight

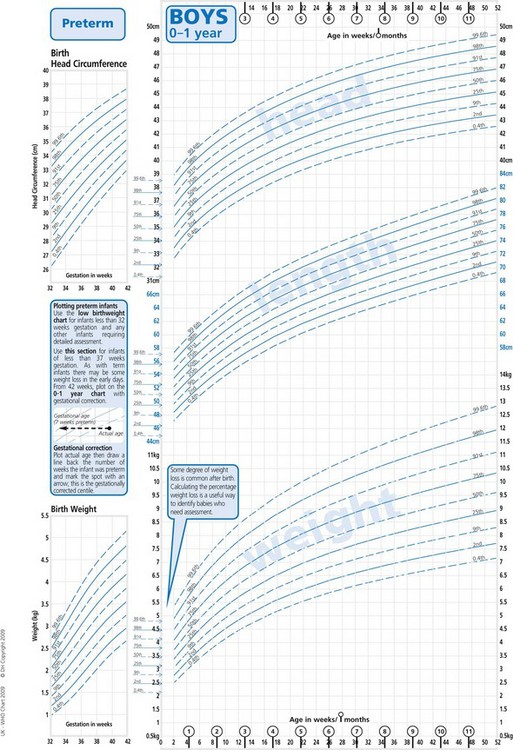

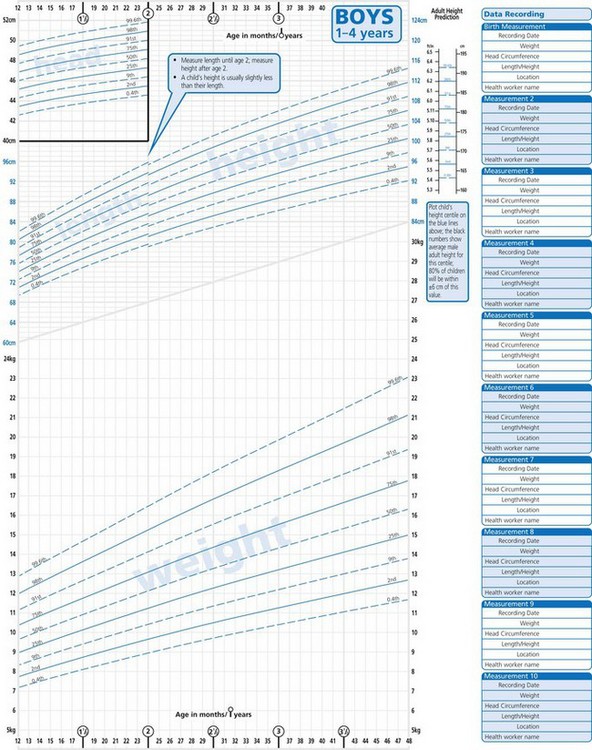

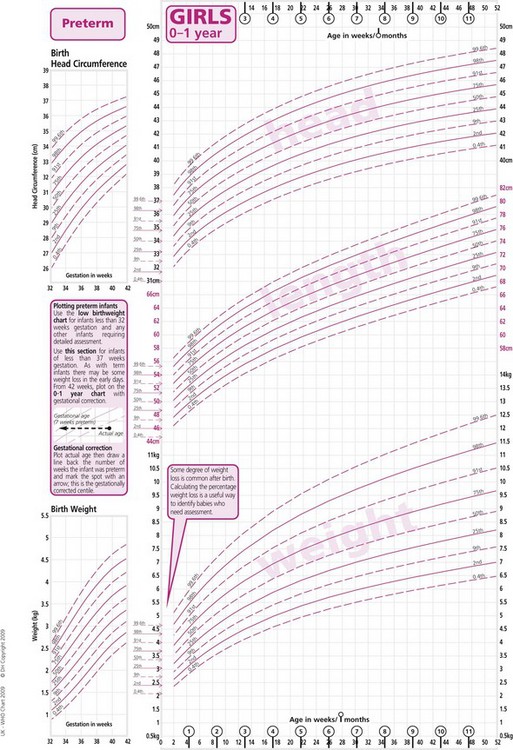

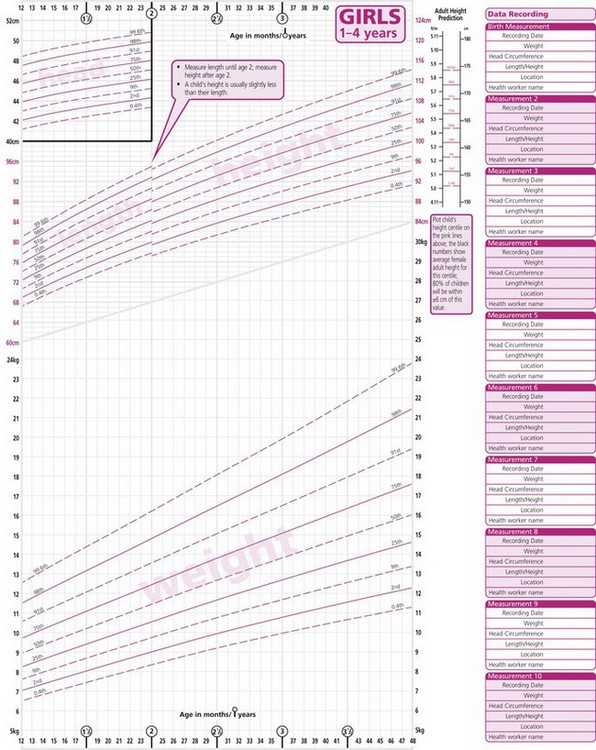

Childhood is a period of growth, the pattern of which may be adversely affected by many disturbances of health as well as social deprivation. Serial measurements of height and weight are therefore essential in the examination of children. In children able to stand, height can be measured against a wall-mounted gauge. Younger children can be measured lying down on special measuring boards. Measurements should be made under standard conditions, and children should be weighed unclothed. If the child keeps any clothes on, this should be noted against the weight so that subsequent weights can be taken with the child wearing the same quantity of clothing. Heights and weights should be compared with those of healthy children of similar sex, age and build on percentile charts. Figures 5.6 and 5.7 show standard height, weight and head circumference charts for UK boys and girls from birth to 4 years. The corresponding charts for children aged 4-18 years are in development at the time of writing – full-size versions of the current charts for 0-20 years are available in clinical settings in the meantime.

Head circumference

In infants under the age of 2 years, the head circumference is a good proxy for linear growth and a much more reliable measurement than height or length. The standard measurement is the largest occipitofrontal circumference out of three using a paper tape. As for height and weight, it is the rate of growth rather than a one-off abnormal value which usually gives cause for concern. Some causes of microcephaly and macrocephaly are listed in Box 5.9. Rather than using a chart showing the head circumference alone, it is more useful to use one that combines head circumference, length and weight percentiles, so that the proportions of each individual child can be compared.

Blood pressure

Abnormalities of blood pressure are uncommon in childhood and, because the measurement of blood pressure can be frightening and technically difficult, it is often only measured when cardiovascular or renal disease is suspected. An electronic monitor will be used in most paediatric settings as manual methods can be inaccurate in small children. There should be a variety of sizes available and the largest cuff which will fit around the upper arm but not extend to the elbow joint should be used. The use of cuffs which are too small will give erroneously high readings. Doppler techniques more accurately measure blood pressure in children, but these are not always available. The blood pressure should be checked in all four limbs where congenital heart disease is suspected to exclude coarctation of the aorta. Normal values of blood pressure at different ages are listed in Table 5.3.

Developmental screening examination

The developmental examination assesses the acquisition of learned skills. Development progresses from head to toe (a child needs to be able to hold his head up before he can sit unsupported). It also requires the loss of primitive reflexes (see Box 5.8) at the appropriate age to progress (a child cannot transfer objects between his hands if he still has a grasp reflex). Developmental progress can be affected by emotional difficulties, environment (e.g. lack of stimulation due to neglect) and illnesses.

All infants should have a simple developmental screening examination at regular intervals. Table 5.1 lists the important milestones. Detailed developmental assessment is a specialist subject, but it is important for all those who examine children to be able to carry out a simple developmental screening examination, and to be aware of all the basic milestones.

It is usual to consider development under four main headings:

Screening for developmental delay involves testing the child’s performance of a few skills in each of the four fields of development, and comparing the results with the average for children of the same age. The range of normal developmental progress is wide, and the milestones shown in Table 5.1 are those of an average normal baby. Delay in all fields of development is more significant than delay in one only, and severe delay is more meaningful than slight delay. Allowance must always be made for those infants who were born prematurely, at least until the age of 2 years, by which time they should have caught up.

Techniques used

Head control

By 4 months, babies can normally keep their head in line with the trunk when pulled from supine to sitting and, when held in the sitting position, will keep their head upright. Before this age, the head lags behind the trunk (Figs 5.8 and 5.9).

Testing vision

Checks of visual acuity are not easy in young babies. By 6 weeks of age, babies should be following their mother with their eyes, and by 6 months they should be able to follow a rolling ball at 3 metres. This is the basis of one method of visual testing at this age. The ability of the child to follow rolling balls of differing diameters gives an accurate assessment of visual acuity. At the 8-month check, the baby should be able to see and pick up an object the size of a raisin at arm’s length. From the age of approximately 2 years, the Sheridan-Gardiner test is used. This is a simple comparison test, with the examiner indicating letters or familiar toys on a board and asking the child to indicate a similar object on a board held by the mother. The acuity is the ability of the child to pick out the smallest objects (see Ch. 19).

Testing hearing

In the past, it was usual to check the hearing for the first time between 6 and 8 months of age using the distraction test (Fig. 5.10). This can still be used as a screening method but has a large observer error and has largely been replaced by a national screening programme for all newborn babies, based on otoacoustic emissions. This measures vibration reflected from the normally functioning cochlea. Additionally, brainstem auditory evoked potentials are used to assess the more vulnerable babies with the risk factors detailed in Box 5.10. This measures electrical activity in the baby’s brain in response to sound. Audiometry and tympanometry are methods used in older children who can cooperate with the tests. They are useful for detecting middle-ear disease or glue ear which is more common in this group of children (see Ch. 20).

Examination of the newborn

The Apgar Score (Box 5.11) is used immediately after birth as a basic indicator of neurological status and will be the first assessment a baby will have in his life. An Apgar Score of 6 or less at 5 minutes after birth is associated with neurological deficit in about 10% of cases. A high Apgar Score at 5 minutes, on the other hand, may not be sensitive to focal brain injury or infarction.

The routine examination of the newborn infant (Box 5.12) is much more useful and is designed to assess the general state of health and to detect congenital abnormalities. It must always be interpreted in the context of the history of the pregnancy and birth and in the knowledge of any known history of inherited disorders in the family. It is recommended that all babies should be examined within the first 24 hours of life, and again before the end of the first week.

Box 5.12 Checklist for examination of the newborn

Primitive reflexes

Primitive responses are present in the normal newborn infant and disappear at variable times in accordance with developmental progress (see Box 5.8). They are responses to specific stimuli, and depend to some extent on the infant’s state of wakefulness. The absence of one or more of these reflexes in the newborn infant may indicate some abnormality of the brain, a local abnormality in the affected limb or a neuromuscular abnormality. The most well-known startle reflex is the Moro reflex (Fig. 5.11). As it is a startle reflex and may make the baby cry, it should be left until the end of the examination. A clearly unilateral response suggests some local abnormality, such as a fracture or brachial plexus injury in the arm on the side that does not respond. Persistence of primitive reflexes beyond the fourth month of life should alert you to the possibility of developmental delay.

Examination of the hips

Examination of the hips is essential but should be left to the end because it can be uncomfortable for the baby. It is performed by carrying out two provocation manoeuvres to demonstrate that the femoral head can be dislocated and then lifted back into the acetabulum, as illustrated in Figures 5.12 and 5.13. It is usual to differentiate between a tendinous ‘click’ and the typical ‘clunk’ of a hip moving in and out of its socket. The latter is more a feeling than an actual noise. Asymmetry of skin creases on the upper posterior thigh and limitation of abduction are signs which do not develop until 6 weeks of age. If there is any doubt about the hip, ultrasound examination should be carried out. Routine ultrasound examination of the hips of all at-risk newborn babies should be carried out to screen for congenital dislocation. At-risk babies are those where there is a breech delivery, a family history of congenital dislocation of the hip (especially if female) and any baby in an unusual intrauterine position.

Screening for genetic disorders

There are a number of disorders for which screening is available by testing at birth, and others that may merit special tests, such as the measurement of white blood cell enzymes, for example gangliosidosis and other lipid-storage disorders. In most of these, tests are not carried out routinely, except in genetically isolated populations or in families known to be at risk. The conditions routinely tested for in all newborn infants in the UK by a heel-prick blood test (commonly known as the ‘Guthrie’ test, although this name specifically refers to the test for phenylketonuria) at 7 days are listed in Box 5.13. Direct DNA analysis for genetic disorders is becoming increasingly available for many inherited disorders.