12 Child Abuse and Neglect

Physical Abuse

Clinical Presentation

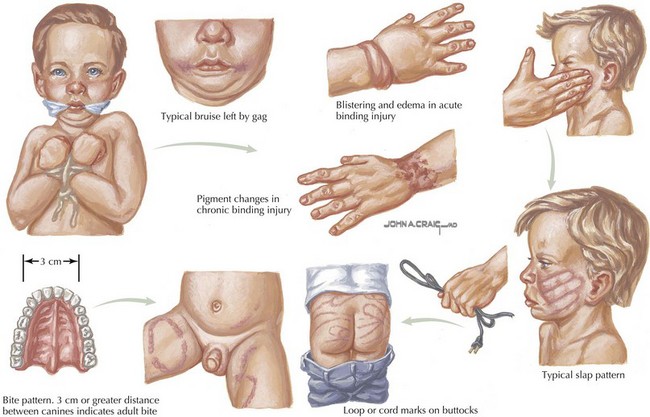

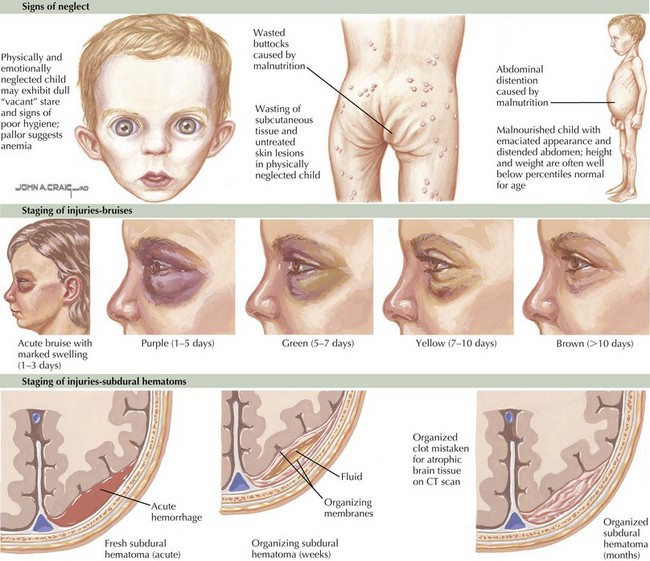

Remove all of the child’s clothing and examine the skin carefully for contusions, abrasions, burns, and lacerations in various stages of resolution. Any bruise on a child who is not yet cruising or walking is unusual. Certain skin lesions are typical for specific types of abuse; such as circular cigarette burns; human bite marks; J-shaped curvilinear or loop-shaped marks from a wire, cord, or belt; circumferential rope burns; “grid” marks from an electric heater; and symmetrical scald burns on the buttocks or extremities (Figure 12-1). Other dermatologic manifestations include cutaneous signs of malnutrition (decreased subcutaneous fat, increased creases), scalp hematomas, signs of trauma to the genital area, and signs of injuries at different stages of healing (Figure 12-2).

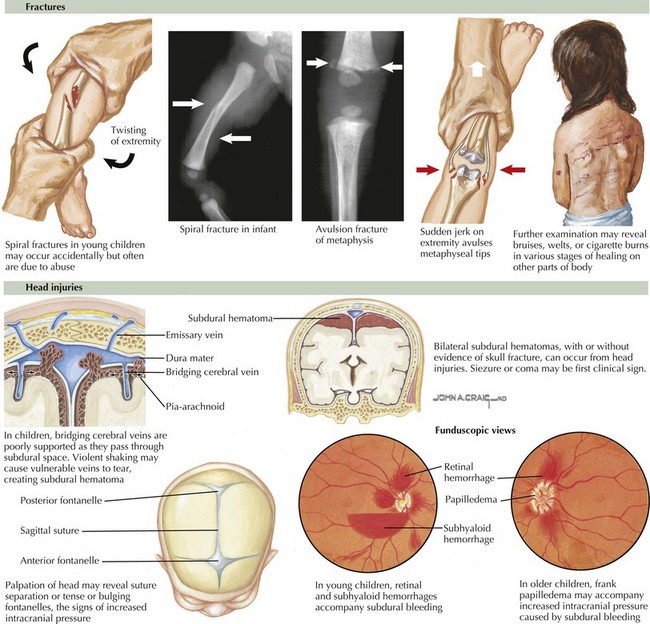

Fractures are suggested by refusal to bear weight or move an extremity, gross deformity, or soft tissue swelling and point tenderness over an extremity. However, most metaphyseal chip fractures are not associated with deformity (Figure 12-3). Neurologic manifestations may include retinal hemorrhages, unexplainable irritability, coma, or convulsions (see Figure 12-3). Finally, an acute abdomen, poisoning, or any traumatic injury that cannot be explained may in fact represent forms of child abuse.

Evaluation and Management

If the parents deny any knowledge of the cause of skin bruises, obtain a complete blood count with differential, platelet count, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and a bleeding time. The differential diagnosis and other possible laboratory studies are shown in Table 12-1.

Table 12-1 Differential Diagnosis and Abnormal Laboratory Studies to Support a Non-abuse Diagnosis

| Findings | Differential Diagnosis | Distinguishing Features and Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Bruising (extensive or deep) | Trauma | Physical examination |

| ITP | Decreased platelets | |

| Hemophilia | Increased PT, PTT | |

| Von Willebrand’s disease | Increased bleeding time | |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Rash on lower extremities; rule out sepsis; normal platelet count | |

| Purpura fulminans | Clinical appearance (findings of sepsis); decreased platelet count | |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | Joint hyperextensibility | |

| Dehydration | Renal or prerenal | Increased BUN, creatinine, urine specific gravity |

| Prerenal: BUN/creatinine >20:1 | ||

| Failure to thrive | Organic or nonorganic | History, physical examination; abnormal studies based on symptoms |

| Abdominal pain | Trauma | Hematuria; increased liver enzymes |

| Tumor | Increased amylase; abdominal ultrasonography; abnormal urinalysis | |

| Infection | Increased WBC, ESR; abdominal ultrasonography | |

| Fractures (multiple or in stages of healing) | Various trauma | |

| Osteogenesis imperfecta | Blue sclerae; radiography: decreased bone density | |

| Rickets | Increased calcium; decreased phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase | |

| Radiography: cupping at ends of long bones, widened metaphysic | ||

| Hypophosphatasia | Decreased calcium, alkaline phosphatase; increased phosphorus | |

| Leukemia | Abnormal peripheral smear, bone marrow, biopsy | |

| Previous osteomyelitis or septic arthritis | Increased WBC, ESR, CRP; positive culture | |

| Neurogenic sensory deficit | Detailed neurologic examination | |

| Metaphyseal or epiphyseal lesions | Trauma | Radiographs consistent with mechanism of injury |

| Scurvy | Radiographs: periosteal elevation; nutritional history | |

| Rickets | (See above) | |

| Menkes syndrome | Decreased copper, ceruloplasmin; hair analysis | |

| Syphilis | Abnormal serology | |

| Little League elbow | History of use | |

| Birth trauma | Neonatal history | |

| Subperiosteal ossification | Trauma | |

| Osteogenic malignancy | Radiographs; biopsy | |

| Syphilis | (See above) | |

| Infantile cortical hyperostosis | No metaphyseal changes | |

| Osteoid osteoma | Dramatic clinical response to aspirin | |

| Scurvy | (See above) | |

| CNS injury | Trauma | CT or MRI scan |

| Aneurysm | CT or MRI scan | |

| Tumor | MRI scan |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CNS, central nervous system; CT, computed tomography; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; WBC, white blood cell.

Sexual Abuse

Evaluation and Management

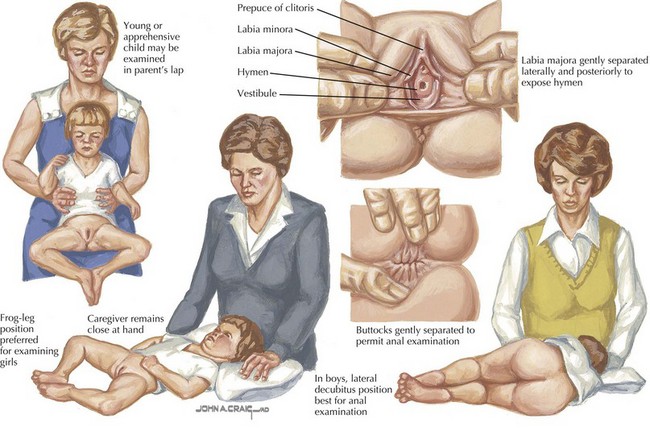

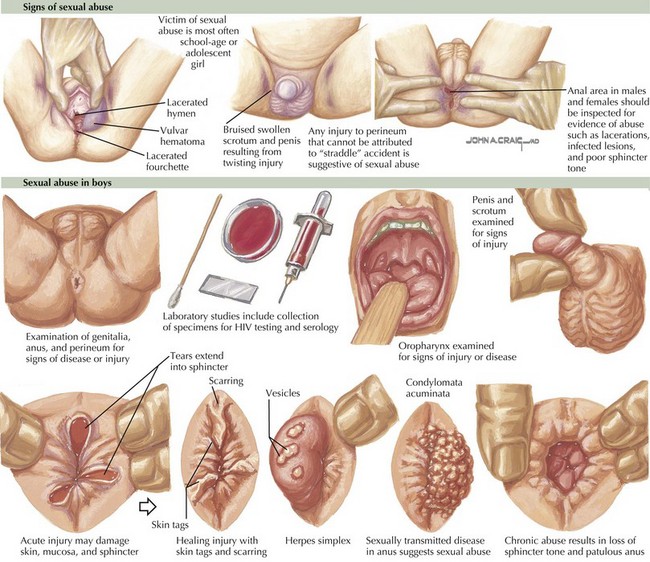

With either prompt or delayed revelation, a careful genital examination is necessary. Perform a perineal-genital examination in young children in the frog-leg, supine, or knee-chest prone position (Figure 12-4). Using a saline-moistened cotton Q-Tip, swab any areas of possible seminal fluid deposition, and placed it on a labeled slide to air dry. In girls, spread the labia with two fingers to examine the hymenal ring, the introitus, and the area between the labia majora and minora. In prepubertal girls, if there are no acute signs of pelvic injury, a speculum examination is not necessary. If there are obvious signs of physical injury (bleeding, lacerations) (Figure 12-5), consult with a pediatric gynecologist or pediatric surgeon on the need for pelvic examination under anesthesia.

In boys, examine the penis and scrotum for bruises, swelling, teeth marks, erythema, and other signs of trauma (see Figure 12-5). In both boys and girls, spread the buttocks with both hands to examine the anus and perineal area. If there are obvious signs of physical injury or severe pain, anoscopy or sigmoidoscopy is indicated under anesthesia if necessary.

Box 12-1 lists the specific laboratory evaluation of a sexually abused child. Obtain gonorrhea and chlamydial cultures from the cervix (postmenarchal), vagina (premenarchal), urethra, rectum, and pharynx if the symptoms of an STD are present. Examine vaginal specimens for the presence of Trichomonas spp. Obtain wet preps from all affected areas to look for sperm up to 6 hours after assault from the mouth and up to 24 hours from the rectum or vagina. If a speculum exam is performed, obtain a Pap smear and ask the hospital laboratory to specifically note the presence of sperm. Immotile sperm are present up to 2.5 weeks after intercourse. Obtain a pregnancy test on all pubertal girls but do not obtain a Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test; a positive result can be used as damaging evidence during subsequent court proceedings. HIV testing may be indicated (at 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year after contact) in areas of high incidences or if the perpetrator has any risk factors for HIV infection.

Give treatment for gonorrhea and chlamydial infections as outlined in Table 12-2 if there is a high suspicion of infection or if the patient is not likely to return (emancipated minor).

Table 12-2 Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Infections in Children

| Infection | Recommended Treatment |

|---|---|

| Chlamydia trachomatis (vulvovaginitis and urethritis) |

Based on data from the following sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines—2006. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep 55(No. RR-11):1-94, 2006.

* Contraindicated in pregnancy.

Pickering LK (ed): Prophylaxis after sexual victimization of preadolescent children. sexual victimization and STIs. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 26. Elk Grove Village, IL, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006, pp 172-177.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Guidelines for the evaluation of sexual abuse of children: subject review. Pediatrics. 1999;103:186-191.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Radiology. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1345-1348.

Atabaki S, Paradise JE. The medical evaluation of the sexually abused child: lessons from a decade of research. Pediatrics. 1999;104:178-186.

Christian CW, Lavelle JM, DeJong AR, et al. Forensic evidence findings in prepubertal victims of sexual assault. Pediatrics. 2000;106:100-104.

Reece RM, Ludwig S. Child Abuse: Medical Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.

Swanston HY, Tebbutt JS, O’Toole BI, et al. Sexually abused children 5 years after presentation: a case-control study. Pediatrics. 1997;100:600-608.