CHAPTER 210 Child Abuse

Child abuse is now recognized as a major cause of serious head injury in children and is second only to motor vehicle–related injuries as a cause of traumatic mortality in the pediatric population.1–3 For the purposes of this chapter, child abuse refers to deliberate, inflicted injury rather than accidental injury occurring in the setting of neglect or inadequate supervision. Because of its nature, the true incidence of inflicted injury remains unknown; many cases are unrecognized as such by health care providers and go unreported. Nonetheless, it has been estimated that nearly one fourth of all hospital admissions for head injury in children younger than 2 years are the result of deliberately inflicted trauma, and these patients suffer disproportionately severe injuries.2,4 Many children with less severe injuries may not receive acute medical attention, thus adding to the difficulties in epidemiologic assessment. It has been postulated that many cases of unexplained developmental delay and retardation are related to head injuries inflicted in infancy.5 The cost of acute and chronic care related to child abuse, as well as the loss of potential from brain damage suffered so early in life and with such high frequency, is enormous and has only recently begun to be recognized.

As our understanding of the biomechanics of head injury in young children has increased, it has become clear that neurologically serious head injury rarely results from common household falls; the only major exception is epidural hematoma.2,6–9 Familiarity with traumatic mechanisms of injury in children and with the clinical findings and evaluation of nonaccidental injury is important for practicing neurosurgeons because a missed diagnosis frequently results in recurrent injury.10 Jenny and colleagues found that the correct diagnosis was missed in nearly a third of children with head injuries caused by abuse who received medical attention and that this failure resulted in medical complications, reinjury, and fatality.11 Furthermore, a neurosurgeon’s opinion about the presumptive mechanism of injury necessary to cause a specific clinical picture is often given a great deal of weight in medicolegal determinations. These decisions affect the patient, siblings, parents, and caretakers in profound ways, and a responsible neurosurgeon must be careful to differentiate what is known and understood from what is conjecture. The role of the physician as witness is discussed in more detail later.

Evaluation of Child Abuse Syndromes

Battered Child Syndrome

Battered child syndrome, described by Kempe and coworkers in 1962, was the first child abuse syndrome to become widely recognized, and its description brought the problem of inflicted injury into focus.12 Battered child syndrome can be seen in infants through adolescents but is most common in children younger than 3 years. Children with this syndrome are brought to medical attention for an unrelated problem or in the setting of a particular acute injury. When evaluated, they are noted to have signs of chronic abuse, which may include poor hygiene, malnutrition, growth retardation, multiple cutaneous bruises of different ages, pattern injuries, burn marks, and skeletal injuries at different stages of healing (Fig. 210-E1).![]()

Central to Kempe and colleagues’ early description of the battered child was the idea that episodes of physical trauma are recurrent rather than isolated events. This principle has been widely supported by subsequent clinical experience, thus making early diagnosis of the syndrome imperative. However, obvious evidence of chronic abuse may not be readily apparent in all children. Therefore, certain types of injuries that occur with greater frequency in the setting of physical abuse should raise the physician’s level of suspicion for nonaccidental causation. Such injuries include spiral fractures of the humerus, spiral fractures of the femur in infants, metaphyseal fractures in infants, duodenal hematomas, “tin ear,” frenulum tears in nonambulatory infants, immersion burns, patterned bruises, and retinal hemorrhages.13–16 In addition, children with preexisting disabilities or prematurity may be at particular risk.17 “Coin rubbing,” seen in Southeast Asian children, and similar therapeutic maneuvers resulting in pattern marks should not be confused with abuse. With respect to neurological trauma, “red flag” injuries include stellate skull fractures, bilateral or multiple skull fractures, and subdural hematomas outside the setting of motor vehicle trauma.1,18 Additionally, the entire range of soft tissue contusions, cephalohematomas (sometimes from severe hair pulling), skull fractures, and intracranial hemorrhages can occur in the setting of inflicted injury.

Shaking-Impact Syndrome

The term shaken baby syndrome was originally coined by Caffey in 1972 to describe infants with acute subdural and subarachnoid hemorrhages, retinal hemorrhages, and periosteal new bone formation at the epiphyseal regions of the long bones.19 Some authors include infants with more chronic extra-axial collections in this category, but for purposes of this discussion, such cases are considered separately. Although the diagnosis of shaken baby syndrome rests on clinical and radiographic features, the name implies a specific mechanism of injury and was derived in part from the case of a nursemaid who admitted shaking several infants injured in her care in an attempt to burp them.19 At about the same time that this syndrome was described, clinical and laboratory evidence of the damaging effects of angular acceleration on the brain was being reported.20–22 Thus, the mechanism of the injuries commonly found in abused infants was postulated to result from “whiplash-shaking” as a form of discipline, and the term shaken baby syndrome became widely accepted as both a diagnosis and a mechanistic description. Support for the validity of the term was found in the observation that many infants with intracranial findings of the syndrome had little if any evidence of blunt impact to the head on initial physical examination. In addition, infants’ relatively large heads, weak neck muscles, and watery brain consistency were thought to render them particularly vulnerable to severe injury from being shaken back and forth by a caretaker.23 The long bone findings, which can also be seen in accidental injuries in which the limbs are jerked or pulled, were likewise thought to occur as a result of violent shaking. Central to the concept of shaken baby syndrome was the idea that caretakers might inflict these injuries unwittingly in the course of a generally acceptable means of discipline, during choking, or even during play.5

Controversy about the mechanism of these injuries arose because of the paucity of a reliable history typically available to the evaluating physician. When a history of trauma is offered, it is usually that of a relatively minor blunt impact, and only rarely is an unsolicited history of shaking obtained. More recently, the term shaken baby syndrome has been questioned because clinical series, autopsies, and biomechanical and radiographic analyses have suggested that many if not most of these infants do, in fact, have evidence of a blunt impact to the head and that the deceleration forces generated by shaking alone are insignificant in comparison to those caused by impact, even when it is against a padded object.24–26 The frequent lack of dramatic cutaneous bruising can be explained by the dissipation of angular deceleration forces across a relatively wide and soft surface.27 It seems likely both from these studies and from careful questioning of perpetrators that although an infant may be shaken, the final thrust involves the head striking a surface, thereby resulting in the high deceleration forces required to cause subdural hemorrhage and frequently severe parenchymal damage. For these reasons, some authors prefer the term shaking-impact syndrome to distinguish the mechanism of shaking in child abuse from shaking during play, shaking to resuscitate, or other less violent scenarios sometimes postulated as being responsible for injuries.28,29 In addition, the frequent findings of long bone injuries, rib fractures, cutaneous bruises, skull fractures, subgaleal and subperiosteal hemorrhages, and focal contusions of the brain parenchyma belie a simple nonimpact cause. Still, the question of whether shaking alone is ever sufficient to cause the brain injuries commonly seen in abused infants remains controversial, and battered child syndrome and shaking-impact syndrome result in a spectrum of overlapping injury types and chronicities seen in patients of varying ages.30

The child abuse evaluation team, if available, is notified, and specific histories from all caretakers involved with the child should be obtained as soon as possible. Although these types of injuries occur in families of all sorts, they are seen most commonly in more fragmented family situations; typically, the infant has multiple caretakers, the parents are young, resources are limited, or other stressful conditions are present. Drugs or alcohol may be involved. One commonly encountered scenario involves a fussy baby being watched by an inexperienced caretaker, such as the mother’s boyfriend. Starling and associates found that perpetrators were fathers, boyfriends, female babysitters, and mothers, in descending order of frequency.31

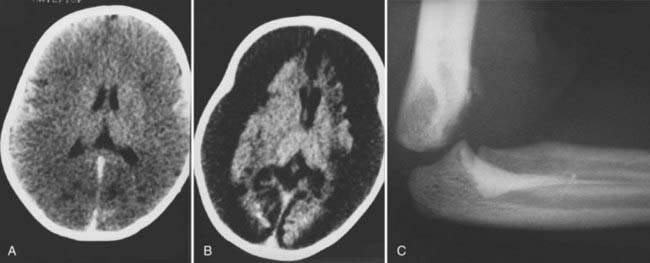

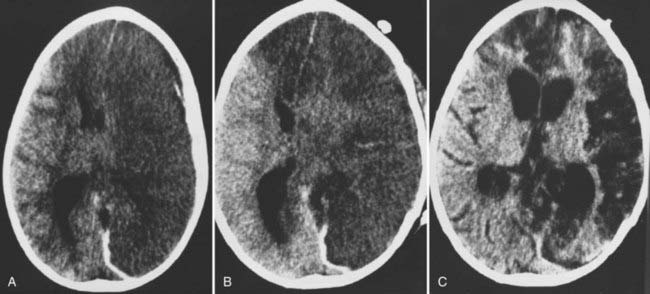

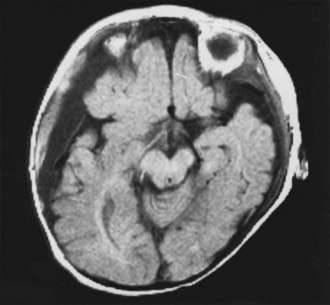

On physical examination, a range of neurological abnormalities may be found, from mild irritability and lethargy to flaccid coma. Some children with seizures may exhibit “bicycling” movements, which can be mistaken for normal spontaneous activity. Even severely injured young infants often show nonspecific withdrawal to noxious stimulation and may even have spontaneous eye opening, but they can usually be identified by a paucity of normal, spontaneous motor activity and by a distinct lack of crying or vigorous grimacing in response to pain. The fontanelle may be full. Careful inspection frequently reveals mild bruising, most often in the parieto-occipital region or, less commonly, in the frontal area, which may be more apparent after several days. Retinal hemorrhages are typically found. Computed tomography shows subdural or subarachnoid hemorrhage ranging from barely perceptible to sizable collections with a mass effect requiring emergency surgery (Figs. 210-1 and 210-2). The hemorrhage may be unilateral or bilateral and has a particular propensity for the posterior interhemispheric space.32 It may result from an impact to the back of the head, displacement of bone across the lambdoid sutures, and subsequent strain on the underlying venous sinuses and deep veins. MRI is frequently superior to computed tomography in demonstrating small subdural hemorrhages and parenchymal contusions; it is particularly helpful if the diagnosis is equivocal, such as when trauma is denied by the caretakers (Fig. 210-3).33 MRI is also a useful screening test for arteriovenous malformations or other vascular anomalies that could cause subarachnoid hemorrhage, particularly when all other tests for associated injuries are unrevealing and the cause of the hemorrhage remains unclear. In rare cases, arteriography may be considered to rule out vascular abnormalities when there is no history or radiographic evidence clearly pointing to trauma and the child has an ictal intracranial hemorrhage.34

In severe cases of shaking-impact syndrome, the brain may lose its normal gray-white differentiation and have the appearance of a large unilateral or bilateral supratentorial infarction. This finding may be visible on the initial scan or may develop 1 to 2 days after injury.35,36 Children with this finding are usually unresponsive on admission and have a dismal prognosis for neurological recovery. The pathophysiology of the so-called black brain seen in these children is incompletely understood but may be due to the synergistic effects of hypoxia, mechanical trauma, and subdural hemorrhage.37–40 In some children, evidence of a high spinal cord injury can be found, and this may contribute to the apnea and poor outcome seen in some cases.41 Spinal injuries in child abuse are discussed in more detail later.

Once the acute management issues have been attended to, as outlined later, a diagnostic evaluation for associated injuries and causes should be pursued. A general screening for other occult injuries should be performed, preferably by the pediatric trauma team. Routine laboratory studies for anemia, thrombocytopenia, visceral injury, and coagulopathy are part of the evaluation; it should be kept in mind that coagulopathy can occur as a result of severe brain injury and does not necessarily imply a preexisting condition.42

As in a battered child, a skeletal survey is mandatory, and a bone scan is sometimes helpful in equivocal cases. A repeat skeletal survey in 2 weeks may increase the yield of diagnosed injuries because of more visible changes with healing.43 A formal ophthalmic consultation with mydriatics, when clinically suitable, should be obtained to document retinal hemorrhages. Although such hemorrhages have been reported in 65% to 95% of patients with shaking-impact syndrome, they are not always present and, conversely, may occasionally be found in children with head injuries from accidental causes and, rarely, after resuscitation.1,2,15,41,44–48 Nonetheless, the presence of retinal hemorrhages adds greatly to the suspicion of nonaccidental injury, especially when they are bilateral and severe.49

No other medical condition fully mimics all the features of full-blown shaking-impact syndrome, but certain features can occur in other conditions. Coagulopathies, vascular anomalies, and anatomic abnormalities such as arachnoid cysts can be associated with subdural hemorrhage.50–52 Osteogenesis imperfecta can be associated with fractures and, rarely, subdural collections, but not with the other features of shaking-impact syndrome.53 Glutaricaciduria can cause progressive neurological decline and subdural collections, sometimes triggered by a viral illness or injury, but it does not feature bony abnormalities or retinal hemorrhages.54 The single most common diagnosis mimicking nonaccidental trauma is accidental injury. In these cases, small epidural hemorrhages or traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhages can be mistaken for subdural bleeding, and unusual subdural hemorrhages can occur when the requisite biomechanics is present in settings not generally associated with this injury; such patients occasionally exhibit retinal hemorrhages as well.47,55 However, in these cases, the history is clear and consistent, and the clinical status is concordant with the forces involved in the injury, without unexplained skeletal or soft tissue injuries.

In many cases, such as those in which there is no history of trauma but the infant has skull fractures and unexplained long bone trauma, the diagnosis is quite clear. In other cases, despite careful evaluation, the mechanism of injury remains obscure. An algorithm has been developed to match the patient’s injury type with associated findings and best history in an attempt to more objectively classify infant head injuries as accidental or inflicted.2 However, until more is understood about the injury thresholds in children of different ages, the pathophysiology of retinal hemorrhages and “black brain,” and the effects of chronic, repeated trauma on the immature nervous system, efforts to assign a definitive mechanism to every suspicious injury will be unsuccessful.

Two additional issues that arise frequently and on which the neurosurgeon may be asked to comment involve the timing of injury and the possibility of multiple, sublethal accidental injuries that might behave synergistically. With respect to the first issue, Willman and coauthors reported on a series of 95 fatal accidental head injuries in children; in all but one patient there was an immediate onset of neurological symptoms and decreased level of consciousness. The one exception was a child with an expanding epidural hematoma.56 Although this study included only a small number of infants, it suggests that a prolonged lucid interval is unlikely in a child with a fatal primary brain injury. This conclusion is in accord with data from accidental trauma in adults and from animal models.27 It should also be kept in mind that care must be taken when attempting to base the time that an injury took place on radiographic findings because they may include a spectrum of abnormalities.36 With respect to the possibility of “second impact syndrome” mimicking child abuse, such rare events have been reported in older children and adults and usually involve well-documented concussive sports injuries resulting in acute subdural or subarachnoid bleeding and brain swelling.57,58 At present, there is no evidence to support the notion that fatal acute traumatic subdural hematoma in otherwise healthy infants occurs from multiple trivial impacts.

Physical Abuse in Older Children

Most physically abused older children brought to medical attention suffer from soft tissue or visceral injuries as a result of direct blows, although intracranial injuries sometimes occur and can be serious or even fatal. The setting is usually that of a biologic or foster family in which deviations from rigid codes of behavior are dealt with by physical punishment and beating, sometimes in an attempt to “save” the child (Fig. 210-4). The parents of both older and younger abused children may have been the victims of child abuse themselves. Occasionally, the perpetrator is psychiatrically impaired, but this is the exception.

Management of Head Injuries from Child Abuse

Acute Subdural Hematoma

Some subdural hematomas resulting from inflicted injury appear identical to those caused by accidental injury and clearly have a mass effect; these hematomas require emergency evacuation in the standard fashion. Even with prompt evacuation, however, changes in the underlying brain often persist or progress and take on the appearance of widespread infarction (see Fig. 210-2A and B). More commonly, subdural and subarachnoid blood is quite diffuse in child abuse injuries and appears as a thin layer without marked compression of the underlying hemisphere. These “smear” collections are generally managed nonoperatively; although aggressive surgical evacuation plus decompression has been reported, this strategy has not been strictly compared with medical management.59 Frequently, the processes leading to the widespread parenchymal loss commonly seen in severely affected infants have already been initiated at the time of arrival at the hospital and may be the result of local compression, apnea, hypoxia, mechanical trauma, or seizures.36,60 Conversely, infants who do not appear critically ill at initial encounter often remain alert and regain a normal level of consciousness quite promptly despite their acute subdural collections and do not eventually suffer large delayed infarctions.

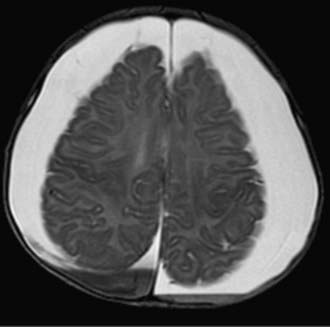

In children in whom gray-white differentiation is lost, brain swelling may be amenable to standard or even extraordinary medical management for increased intracranial pressure, but conventional therapy rarely if ever prevents the swollen brain from progressing to severe atrophy (see Fig. 210-2). In very young infants, brain swelling may not be a life-threatening problem because the skull simply expands to accommodate the swelling; these infants survive, but in a devastated state (see Fig. 210-1B). Because of this dismal outlook, the role of more aggressive measures, including intracranial pressure monitoring, is controversial in this population.61,62

Chronic Extracerebral Fluid Collection

Large, bilateral, chronic extracerebral fluid collections composed of old blood products or proteinaceous cerebrospinal fluid are sometimes discovered in infants. The term chronic subdural hematoma is often applied to these collections, although the content of the accumulation may vary from thin, watery fluid resembling cerebrospinal fluid to the thick “motor oil” often associated with adult chronic subdural hematomas. Even modern, sophisticated imaging techniques such as MRI may not be able to distinguish fluid in the subdural space from that in the subarachnoid space, and the term chronic extracerebral fluid collection is probably more accurate.63 A definite history of antecedent trauma may not be obtained, and the question of child abuse often arises.

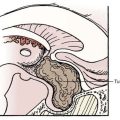

Guthkelch pointed out that sudden acceleration and deceleration of the head, even without direct impact, can result in the tearing of cortical bridging veins in adults.23 Chronic subdural hemorrhage resulting from relatively small force occurs most commonly in elderly individuals in whom the bridging veins cross a widened subarachnoid space and are “on stretch” at baseline. Another example of this phenomenon occurs in children or adults with ventricular shunts in whom the extracerebral space enlarges as the ventricles become smaller; these patients are well known to be susceptible to subdural hemorrhage from relatively trivial trauma. Whether a similar mechanism may be at work in infants with enlarged extracerebral spaces, perhaps because of so-called external hydrocephalus or atrophy, is not entirely clear, although this phenomenon is occasionally witnessed (Fig. 210-5). In this situation, tearing of bridging veins and the arachnoid from relatively mild trauma, such as might occur accidentally, could theoretically result in a mixed collection of blood and cerebrospinal fluid in both the subdural and subarachnoid spaces.

With respect to the issue of whether chronic subdural collections represent a manifestation of child abuse, several key questions remain unanswered. First, what are the mechanical thresholds for hemorrhage in a child with enlarged extracerebral spaces? Second, do some infants with shaking-impact syndrome escape acute medical attention only to be seen in delayed fashion with chronic collections? Finally, what is the effect of repeated injuries, either inflicted or accidental?10 Such a situation could produce atrophy, thus lowering the mechanical threshold for subdural hemorrhage, as it does in the elderly, and result in recurrent hemorrhage with each new injury. Ultrastructural evaluation of the membranes that often develop around chronic bloody collections reveals abnormal capillary fragility, and repeated hemorrhage into established extracerebral fluid collections is now believed to account for their enlargement.64 Perhaps in these situations, when the anatomy of the brain and extracerebral space is no longer “normal,” the biomechanical threshold for injury is sufficiently lowered that either shaking without impact or trivial accidental trauma could result in subdural hemorrhage.

Infantile chronic extracerebral collections are most frequently detected between 1 and 14 months of age, with a preponderance in the younger age group.23,65,66 For reasons that are not clear, most series report a higher incidence in male infants. In some instances, a specific cause can be established by history or laboratory analysis. Accidental trauma, coagulopathy, and postshunt cerebral collapse accounted for about 33% of cases, and documented or suspected child abuse accounted for an additional 44% in one series.65 Documented birth trauma accounts for a relatively small number of cases. An extremely rare cause of subdural hematoma in infancy is a form of osteogenesis imperfecta, a genetic condition affecting collagen metabolism that results in fragile bones.53 Despite its rarity, this condition is occasionally invoked to defend an alleged perpetrator of child abuse in criminal proceedings. The condition is sporadic in about two thirds of cases, and absence of a family history does not rule out the disease. Nonetheless, as mentioned previously, most forms of osteogenesis imperfecta have specific clinical signs, such as blue sclerae, hypoplastic teeth, and hearing abnormalities, that point to the diagnosis, and biochemical abnormalities in type I collagen may be demonstrated.67 Glutaricaciduria has also been associated with chronic extracerebral collections and neurological decline in infancy.54

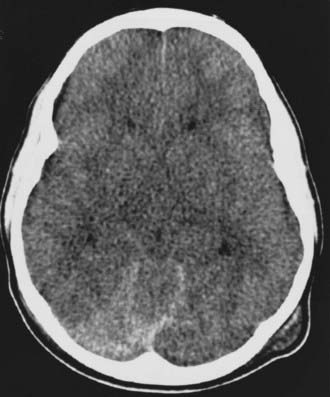

The principal clinical features of extracerebral fluid collections in infancy arise from chronic intracranial hypertension and consist of macrocephaly, fullness of the fontanelle, “sunsetting,” vomiting, sleepiness, and irritability. The child’s clinical appearance often suggests hydrocephalus, and only imaging studies reveal the true nature of the problem. Seizures may occur as a result of cortical irritation. Anemia may also accompany large fluid collections, probably arising from nutritional deficiency rather than blood loss into the extracerebral spaces.66

The diagnosis is made by transfontanelle ultrasonography, computed tomography, or MRI examination of the head. An extra-axial fluid collection is seen, usually with imaging characteristics consistent with protein-rich fluid or chronic blood. There may be multiple laminations composed of blood of varying ages.65 Skull radiographs and long bone films should be obtained to search for evidence of fracture, and a child abuse evaluation should be initiated. MRI readily distinguishes high-protein or bloody extra-axial collections from the extra-axial cerebrospinal fluid collections that are commonly seen in asymptomatic, but sometimes macrocephalic infants with benign external hydrocephalus, which requires no treatment. Whether such enlarged extra-axial cerebrospinal fluid spaces predispose to hemorrhage after minor trauma remains unclear, but it does not seem to be a common occurrence.

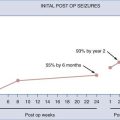

Therapy for the chronic hemorrhagic extracerebral collections of infancy has undergone a significant evolution over the past 5 decades. Although small, asymptomatic collections can sometimes be monitored conservatively, large collections with a mass effect, neurological symptoms, or cranial enlargement require intervention. Historically, such collections were treated by large craniotomies with attempted resection of the investing membranes and, more recently, by reduction cranioplasty and lowering of the sagittal sinus in an attempt to treat the craniocerebral disproportion that may accompany the condition.68,69 Current practice is to manage symptomatic collections initially by intermittent fontanelle taps and to insert a shunt to the pleural or peritoneal space if the collections do not resolve in 2 or 3 weeks.65 Other authors favor proceeding directly to shunting once the diagnosis is established (Fig. 210-6).70 A unilateral shunt is generally sufficient, although there have been cases in which bilateral collections had poor communication and required bilateral shunts.70,71 It has been suggested that computed tomography–subdurography, in which contrast dye is instilled via the fontanelle into the collection, could predict the need for bilateral shunts.72 An alternative is simply to place bilateral shunts routinely.

FIGURE 210-6 Extra-axial collections in an infant with a rapidly enlarging head. A subdural-peritoneal shunt was placed.

The outcome of children with treated chronic extracerebral collections is highly variable. Approximately 50% can be expected to have normal development, but 30% will be moderately disabled and 13% will be severely disabled.72 Child abuse as the cause of the collection is a particularly poor prognostic factor, presumably because of the underlying brain parenchymal damage that occurred at the time of the original injury. Series that contain abused children probably include a certain number of children with brain atrophy as a contributing cause of the delayed extracerebral collections, which would tend to increase the number of poorer outcomes.

Ex Vacuo Cerebrospinal Fluid Collection

Young children who have suffered documented severe closed head injuries because of child abuse and in whom extracerebral collections develop weeks or months afterward pose a special problem. The pathophysiology of this condition remains poorly understood, but as discussed earlier, large areas of low-density “black brain” evolve to frank infarction in most instances.25,37 Serial computed tomography or MRI performed some months after the initial injury shows severe atrophy with a prominent sulcal pattern, loss of white matter, and massive extracerebral collections of slightly proteinaceous or cerebrospinal fluid density (see Fig. 210-1B). These are the result of brain dissolution and shrinkage and are invariably accompanied by severe neurological damage. Head circumference may increase somewhat but tends to plateau over time. In general, surgical drainage of this sort of posttraumatic collection does not result in clinical improvement. In rare cases, drainage can be considered if there is clinical deterioration consistent with the time course of the collection’s appearance or overt signs or symptoms of intracranial hypertension.

Spinal Injury Caused by Child Abuse

In view of the commonly assumed “whiplash” pathophysiology of child abuse, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the spine in clinical and autopsy series. Several aspects of the spine of infants and children render it particularly vulnerable to damage as a result of flexion-extension forces: (1) the interspinous ligaments, posterior joint capsule, and cartilaginous end plates are elastic; (2) the facet joints are horizontally oriented; (3) the anterior portion of the vertebral bodies is wedged; (4) the uncinate processes are flat and therefore ineffective in withstanding flexion-rotation forces; (5) the head of an infant is somewhat large in relation to the underdeveloped neck musculature; and (6) the atlanto-occipital joint of an infant is inherently unstable, and weak supporting ligaments allow the arch of Cl to invert within the foramen magnum during extension and compress the vertebral arteries.73–76 Furthermore, it is now clear that devastating neurological injury can occur in children without bony fractures or other radiographic abnormalities, thus making spinal cord injury difficult to detect without sophisticated radiographic imaging procedures.77 The incidence of spinal injury in the setting of child abuse is probably underappreciated because overwhelming brain injury may mask an associated injury to the cervical spinal cord. Even at autopsy, the brain is often removed at the cervicomedullary junction, and the spinal cord is not examined at all.

There is evidence, however, that a significant percentage of fatally injured abused infants have autopsy findings of subdural and epidural hemorrhage and contusion of the high cervical cord, which may contribute to the morbidity and mortality.41 Because most of the information regarding spinal injuries in child abuse has come from autopsy series, it may be that these injuries are usually fatal and that survivors are unlikely to be affected. Indeed, it is rare to have a clinically detected spinal cord injury in a child with a recoverable brain injury. Nonetheless, it is conceivable that apnea from transient spinal cord compression in association with a shaking-impact injury might significantly contribute to the cerebral insult that is so prominent in child abuse cases. Compression of the vertebral arteries has also been considered, although the distribution of the posterior circulation is usually spared in child abuse cases with widespread infarction.

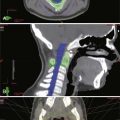

Spinal fracture and overt spinal instability appear to be uncommon aspects of nonaccidental trauma to infants but might be underrecognized.78 Nevertheless, it is appropriate to immobilize the neck and obtain screening radiographs of the spine as part of the evaluation of suspected child abuse. If MRI of the brain is performed, a screening study of the upper cervical region can also be obtained, although findings in survivors are unusual. Occasionally, spinal injuries are seen in “battered” children and appear to occur as a result of extreme hyperflexion or hyperextension forces applied to the immature spine (Fig. 210-7).79

Outcome of Head Injuries from Child Abuse

It has been recognized in large series of pediatric head injury that severely head-injured infants have a worse prognosis than older children do, probably because of the preponderance of inflicted injuries in this age group.80,81 Mortality in abused children with head injuries ranges between 10% and 27% in various series, although exact figures are difficult to compile because of differences in the definition of child abuse and in referral populations.2,24,26,44,82 Nonetheless, it is clear that this cause of head injury correlates with high mortality.

Morbidity in survivors of inflicted injury is uncertain because long-term follow-up of patients injured in infancy is, by nature, difficult and outcome may depend on factors other than the brain injury itself. Nonetheless, it is obvious that children with infarction and severe brain atrophy remain severely disabled; children with bilateral diffuse hypodensity who survive are blind, nonverbal, nonambulatory, and severely developmentally delayed.62 The long-term deficits of children who are more mildly injured are less well studied, but it appears that the majority of children suffer persistent deficits, with less than a third approaching age-appropriate functioning.60–6283

With respect to visual problems, the retinal hemorrhages resolve over time, but amblyopia may develop if the macula is obscured by hemorrhage for a prolonged period, and therefore close follow-up is recommended. Retinal detachment frequently results in marked visual compromise and may require repair to optimize recovery. Retinal folds may also adversely affect visual outcome.84

Another relevant outcome measure is risk for recurrence of physical abuse. In one series, more than half of abused children had radiographic or autopsy evidence of previous physical abuse.10 In a group of children in whom the diagnosis of abusive head injury was missed at the initial medical contact, 27.8% were reinjured before the diagnosis was made.11 Other series found even higher rates of reinjury.83 These data suggest that a child who is returned to the caretakers responsible for the injury is at high risk for repeated trauma, and for this reason, child welfare agencies commonly place a child in protective custody when abuse is suspected. A more detailed discussion of the social and legal aspects of child abuse in the United States can be accessed on the Expert Consult site![]() .

.

Medicolegal Considerations in Child Abuse

Physician Responsibility and Liability

The recognition of child physical abuse as a theoretically preventable problem has led to the development of child abuse legislation. In 1963, the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare’s Children’s Bureau developed principles and suggested language for states to use in generating child abuse statutes.85 Within a few years, all states in the country had developed reporting laws for child physical abuse. In 1974, the Federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act required states to expand reporting laws to include other forms of abuse and provided grants to states meeting the new standards. Over the past 30 years, each state has developed criminal and civil laws to define child abuse. Although each state’s law differs, they all are intended to identify and protect children who are victims of child abuse.

Each state’s child abuse law identifies individuals who are required to report suspected abuse. These mandated reporters generally include all adults who come in contact with children in some professional capacity, including physicians, teachers, librarians, dentists, and others. Mandated reporters are required to identify children, based on reasonable knowledge and experience, who may be the victims of abuse. Reporting laws require a suspicion of abuse for reporting, not proof that abuse has occurred. Although anyone may report suspected cases, professionals tend to report more true cases of abuse than the general public does.86 Physicians are not exempt from filing reports of suspected abuse despite the principles of doctor-patient confidentiality.

Civil and Criminal Judicial Intervention

State laws define intentional or reckless acts that cause harm to a child as crimes. The criminal system addresses whether an individual is responsible for the child’s injuries. The decision to prosecute is made by a prosecuting attorney (working on behalf of the state) after an investigation is completed by law enforcement. The purpose of a criminal trial is to determine whether a crime has been committed and whether the defendant was the perpetrator of that crime. The rules of evidence and the formality of the proceedings are stricter in a criminal trial than in a civil hearing (Table 210-E1). In general, severe cases of physical abuse, including abusive head trauma, are brought to criminal trial. The charges against the defendant are determined by the prosecutor and are dependent on the facts of the case. The guilt of the defendant is determined either by a jury or by a judge and a jury, the option being with the defendant. Penalties for guilt are dependent on the charges filed, the past criminal record of the defendant, and other circumstances regarding the case and can range from probation to lifetime incarceration.

TABLE 210-E1 Comparison of Civil and Criminal Child Abuse Proceedings

| CIVIL | CRIMINAL | |

|---|---|---|

| Laws | State child protection laws | State criminal codes for specific crimes |

| Focus | Child protection | Offender accountability |

| Need to prove | Child was injured by nonaccidental means | Defendant injured child at specific time |

| Fact finder | Judge | Judge or judge and jury |

| Maximum penalty | Removal of child from home | Incarceration |

| Rules of evidence | Lenient | Strict |

| Burden of proof | Predominance of the evidence | Beyond a reasonable doubt |

Adapted from Ludwig S, Kornberg A, eds. Child Abuse and Neglect: A Medical Reference. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1991:424.

The Physician as a Witness

Physician testimony is often needed in civil or criminal trials or in both. The principles that apply to child abuse cases may be familiar to neurosurgeons from other medicolegal realms, such as medical malpractice, but bear repeating in the present context. To begin with, the physician can testify as either a fact witness or an expert witness. This legal distinction is designed to prevent witnesses of fact, who are being asked only to report their actions or observations, from expressing personal opinions based on conjecture or bias that might unfairly influence a jury. A treating physician may be subpoenaed to court to provide information regarding only the child’s treatment or care, thus serving as a fact witness. Although fact witnesses are not permitted to offer opinions or conclusions derived from the facts of a case, an expert witness is expected to do just that. An expert witness is an individual who by training, education, and clinical experience has knowledge in a particular field that goes beyond what a layperson would know. After hearing the credentials of the witness, the judge determines whether the witness qualifies as an expert and then allows the witness to offer opinions and conclusions. Based on this broad definition, most neurosurgeons would be considered “expert” with respect to head injuries and their causes. The concept of “expert” as it applies to criminal testimony in child abuse cases poses some practical problems. First, the court’s definition of an expert differs from that of the medical community; the court legally allows expert testimony from medical scientists who have an advanced degree but no true expertise on the subject under question. Second, an expert witness should be thought of as an educator of the judge or a jury; the facts and opinions of the expert should assist the jury in determining the guilt or innocence of the defendant. Even though many clinicians in various specialties, including neurosurgery, have some familiarity with abusive head injuries, it is often tempting to infuse facts with opinions in an area in which considerable uncertainty often exists. Brent reviewed the problem of irresponsible expert witness testimony and outlined the qualities of a responsible expert, who should be a nonpartisan scholar with publications in the field under question, as well as an active clinician for whom legal activities represent only a minor part of the professional activities.87

Preparing for Court Testimony

Involvement in a civil or criminal case can sometimes prove frustrating for the physician. The procedures, language, and adversarial flavor of the courtroom are foreign to the physician, and despite an attempt to protect the child or hold the perpetrator responsible for hurting a child, the outcome may not be favorable. Fortunately, the majority of reported cases of child abuse do not require court involvement, and it is only a minority of abuse that is severe enough to warrant criminal prosecution.88

Legal and Social Outcomes of Child Physical Abuse

Few studies have examined the legal outcome of physical abuse cases. Showers and Apolo studied the legal disposition of 72 cases of fatal child abuse that occurred in Columbus, Ohio, from 1965 to 1984.89 Of the 72 deaths studied, the majority were the result of severe head trauma. In 51% of the cases, insufficient evidence existed to file charges against the suspected perpetrator. Of the 27 suspects charged with a crime, 5 were acquitted, one case resulted in a hung jury and the charges were dismissed, and 21 were convicted of a crime. Of the 21 convictions, 9 pled guilty. The sentences ranged from 6 months of probation to 15 years to life in prison. Fourteen percent of the convicted individuals served no prison sentence, and 19% served less than 1 year. Females were less likely than males to be charged, convicted, or imprisoned. The number of suspects charged and convicted varied greatly between the first and second decades studied, probably because of increased awareness of the problem of child abuse and improved identification and investigation of physical abuse. More recently, Keenan and colleagues prospectively monitored the judicial case flow of criminal cases related to abusive head trauma in North Carolina. The authors compared the original and final charges filed against the defendant, as well as sentencing decisions, and found that the original and final charges varied greatly. Fatal injuries resulted in higher felony charges, and sentences ranged from probation to life in prison. Severe sentences were associated with minority race, thus suggesting sentencing bias toward harsher sentences for minority perpetrators.90,91

Despite the research that has been done in the past 30 years, there has been little focus on the long-term effects of physical abuse, partly because of the relatively recent professional recognition of child abuse. Widom carefully studied the effects of physical abuse on subsequent delinquent and adult criminal and violent criminal behavior.92 In this study, Widom identified a large sample of validated cases of child abuse from the 1960s, matched them with nonabused children, and analyzed the subsequent criminal records for both groups. Although the majority of the abused children did not become delinquents or adult criminals, being abused as a child increased the risk for juvenile delinquency, adult criminal behavior, and violent criminal behavior.

Martin and Elmer described the social functioning of a small group of adults who were severely battered as children in the 1960s.93 Although children who sustained head trauma were included in the group, these subjects were not analyzed separately. Because of both the small sample size studied and the complexity of factors that determine adult social skills, no clear relationship developed between a history of severe abuse and adult functioning. The adult victims of abuse tended to be resentful and suspicious, but not overtly aggressive. Some exhibited limited autonomy, whereas others were competently raising families and holding jobs. Overall, outcomes for the individuals studied were extremely variable, thus supporting the need for further careful investigation in this field.

Much of the recent effort in prevention has focused on identifying child, parent, and caretaker factors that increase the risk for abuse. Thus, although child abuse occurs in a wide variety of situations, particular risk factors have been identified, such as young parents, low socioeconomic status, unstable family situations, disability or prematurity of the child, and male caretakers.17,31,94 Efforts to target future or current high-risk caretakers for specific interventions, including education in parenting skills, stress management, and appropriate choices in surrogate childcare, might best direct prevention resources toward those most likely to benefit.

Prevention of all forms of abuse and neglect would require the elimination of poverty and violence from society, the development of comprehensive support systems for both new parents and nuclear families, and improved education of the children and young adults who represent the next generation of parents. Comprehensive health care reform is needed to provide adequate medical insurance to the millions of children who are currently uninsured. Studies have shown that a public health nurse or a layperson acting as a home visitor can prevent abuse.95–99 Many school districts have incorporated child abuse prevention into education curricula.97 Finally, specific campaigns against “shaking” injuries have been developed to educate parents about the dangers of shaking infants.98 To date, these programs have involved participants learning about the purported dangers of shaking, but they have not been evaluated for effectiveness in preventing inflicted head trauma.

Billmire Billmire ME, Myers PA. Serious head injury in infants: accident or abuse? Pediatrics. 1985;75:340-342.

Caffey J. The whiplash shaken infant syndrome: manual shaking by the extremities with whiplash-induced intracranial and intraocular bleedings, linked with residual permanent brain damage and mental retardation. Pediatrics. 1974;54:396-403.

Dias MS, Backstrom J, Falk M, et al. Serial radiography in the infant shaken impact syndrome. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1998;29:77-85.

Duhaime AC, Gennarelli TG, Thibault LE, et al. The shaken baby syndrome: a clinical, pathological, and biomechanical study. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:409-415.

Hymel KP, Abshire TC, Luckey DW, et al. Coagulopathy in pediatric abusive head trauma. Pediatrics. 1997;99:371-375.

Jenny C, Hymel KP, Ritzen A, et al. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA. 1999;281:621-626.

Johnson DL, Boal D, Baule R. Role of apnea in nonaccidental head injury. J Pediatr Neurosurg. 1995;23:305-310.

Parent AD. Pediatric chronic subdural hematoma: a retrospective comparative analysis. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1992;18:266-269.

Willman KY, Bank DE, Senac M, et al. Restricting the time of injury in fatal inflicted head injuries. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21:929-940.

1 Billmire ME, Myers PA. Serious head injury in infants: accident or abuse? Pediatrics. 1985;75:340-342.

2 Duhaime AC, Alario AJ, Lewander WJ, et al. Head injury in very young children: mechanism, injury types, and ophthalmologic findings in 100 hospitalized patients younger than 2 years of age. Pediatrics. 1992;90:179-185.

3 Gotschall CS. Epidemiology of childhood injury. In: Eichenberger MR, editor. Pediatric Trauma: Prevention, Acute Care, Rehabilitation. St. Louis: Mosby–Year Book; 1993:16-19.

4 Ewing-Cobbs L, Kramer L, Prasad M, et al. Neuroimaging, physical, and developmental findings after inflicted and noninflicted traumatic brain injury in young children. Pediatrics. 1998;102:300-307.

5 Caffey J. The whiplash shaken infant syndrome: manual shaking by the extremities with whiplash-induced intracranial and intraocular bleedings, linked with residual permanent brain damage and mental retardation. Pediatrics. 1974;54:396-403.

6 Helfer RE, Slovis TL, Black MB. Injuries resulting when small children fall out of bed. Pediatrics. 1977;60:533-535.

7 Joffe M, Ludwig S. Stairway injuries in children. Pediatrics. 1988;82:457-461.

8 Nimityongskul P, Anderson L. The likelihood of injuries when children fall out of bed. J Pediatr Orthop. 1987;7:184-186.

9 Shugerman RP, Paez A, Grossman DC, et al. Epidural hemorrhage: is it abuse? Pediatrics. 1996;97:664-668.

10 Alexander R, Crabbe L, Sato Y, et al. Serial abuse in children who are shaken. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:58-60.

11 Jenny C, Hymel KP, Ritzen A, et al. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA. 1999;281:621-626.

12 Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, et al. The battered-child syndrome. JAMA. 1962;181:105-112.

13 Ludwig S. Child abuse. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1988:1127-1163.

14 Hanigan WC, Peterson RA, Njus G. Tin ear syndrome: rotational acceleration in pediatric head injuries. Pediatrics. 1987;80:618-622.

15 Harcourt B, Hopkins D. Ophthalmic manifestations of the battered-baby syndrome. BMJ. 1971;3:398-401.

16 Elner SG, Elner VM, Arnall M, et al. Ocular and associated systemic findings in suspected child abuse. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:1094-1101.

17 Klein M, Stern L. Low birth weight and the battered child syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1971;122:15-18.

18 Meservy CJ, Towbin R, McLaurin RL, et al. Radiographic characteristics of skull fractures resulting from child abuse. Am J Radiol. 1987;149:173-175.

19 Caffey J. On the theory and practice of shaking infants: its potential residual effects of permanent brain damage and mental retardation. Am J Dis Child. 1972;124:161-169.

20 Ommaya AK, Yarnell P. Subdural hematoma after whiplash injury. Lancet. 1962;2:237-239.

21 Ommaya AK, Faas F, Yarnell P. Whiplash injury and brain damage: an experimental study. JAMA. 1968;204:285-289.

22 Ommaya AK, Gennarelli TA. Cerebral concussion and traumatic unconsciousness: correlation of experimental and clinical observations on blunt head injuries. Brain. 1974;97:633-654.

23 Guthkelch AK. Infantile subdural hematoma and its relationship to whiplash injuries. BMJ. 1971;2:430-431.

24 Duhaime AC, Gennarelli TG, Thibault LE, et al. The shaken baby syndrome: a clinical, pathological, and biomechanical study. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:409-415.

25 Duhaime AC, Sutton LN, Schut L. The “shaken baby syndrome”: a misnomer? J Pediatr Neurosci. 1988;4:77-86.

26 Hahn YS, Raimondi AJ, McLone DG, et al. Traumatic mechanisms of head injury in child abuse. Childs Brain. 1983;10:229-241.

27 Gennarelli TA, Thibault LE. Biomechanics of head injury. In: Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS, editors. Neurosurgery, vol 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1985:1531-1536.

28 Bruce DA, Zimmerman RA. Shaken impact syndrome. Pediatr Ann. 1989;18:482-489.

29 Duhaime AC, Christian CW, Rorke LB, et al. Nonaccidental head injury in infants—the “shaken baby syndrome.”. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1822-1829.

30 Alexander R, Sato Y, Smith W, et al. Incidence of impact trauma with cranial injuries ascribed to shaking. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:724-726.

31 Starling SP, Holden JR, Jenny C. Abusive head trauma: the relationship of perpetrators to their victims. Pediatrics. 1995;95:259-262.

32 Zimmerman RA, Bilaniuk LT, Bruce D, et al. Computed tomography of craniocerebral injury in the abused child. Radiology. 1979;130:687-690.

33 Sato Y, Yuh WTC, Smith WL, et al. Head injury in child abuse: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1989;173:653-657.

34 Plunkett J. Sudden death in an infant caused by rupture of a basilar artery aneurysm. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1999;20:45-47.

35 Feldman KW, Brewer DK, Shaw DW. Evolution of the cranial computed tomography scan in child abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19:307-314.

36 Dias MS, Backstrom J, Falk M, et al. Serial radiography in the infant shaken impact syndrome. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1998;29:77-85.

37 Whyte KM, Pascoe M. Does “black” brain mean doom? Computed tomography in the prediction of outcome in children with severe head injuries: “benign” vs “malignant” brain swelling. Australas Radiol. 1989;33:344-347.

38 Duhaime AC, Bilaniuk L, Zimmerman R. The “big black brain”: radiographic changes after severe inflicted head injury in infancy. J Neurotrauma. 1993;10(suppl 1):S59.

39 Johnson DL, Boal D, Baule R. Role of apnea in nonaccidental head injury. J Pediatr Neurosurg. 1995;23:305-310.

40 Shaver E, Duhaime AC, Curtis M, et al. Experimental acute subdural hematoma in infant piglets. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1996;25:123-129.

41 Hadley MN, Sonntag VKH, Rekate HL, et al. The infant whiplash-shake syndrome: a clinical and pathological study. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:536-540.

42 Hymel KP, Abshire TC, Luckey DW, et al. Coagulopathy in pediatric abusive head trauma. Pediatrics. 1997;99:371-375.

43 American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Radiology. Diagnostic imaging in child abuse. Pediatrics. 1991;87:262-264.

44 Ludwig S, Warman M. Shaken baby syndrome: a review of 20 cases. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:104-107.

45 Luerssen TG, Huang JC, McLone DG, et al. Retinal hemorrhages, seizures, and intracranial hemorrhages: relationships and outcomes in children suffering traumatic brain injury. In: Marlin AE, editor. Concepts in Pediatric Neurosurgery, vol 11. Basel: Karger; 1991:87-94.

46 Johnson DL, Braun D, Friendly D. Accidental head trauma and retinal hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:234-235.

47 Christian C, Taylor AA, Hertle R, et al. Retinal hemorrhages due to accidental household trauma. J Pediatr. 1999;135:125-127.

48 Goetting MG, Sowa B. Retinal hemorrhage after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in children: an etiologic reevaluation. Pediatrics. 1990;85:585-588.

49 Green MA, Lieberman G, Milroy CM, et al. Ocular and cerebral trauma in non-accidental injury in infancy: underlying mechanisms and implications for paediatric practice. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:282-287.

50 Yoffe G, Buchanan GR. Intracranial hemorrhage in newborn and young infants with hemophilia. J Pediatr. 1988;113:333-335.

51 Ryan CA, Gayle M. Vitamin K deficiency, intracranial hemorrhage, and a subgaleal hematoma: a fatal combination. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1992;8:143.

52 Parsch CS, Krauss J, Hofmann D, et al. Arachnoid cysts associated with subdural hematomas and hygromas: analysis of 16 cases, long-term follow-up, and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:483-490.

53 Tokoro K, Nakajima F, Yamataki A. Infantile chronic subdural hematoma with local protrusion of the skull in a case of osteogenesis imperfecta. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:595-598.

54 Haworth JC, Booth FA, Chudley AE, et al. Phenotypic variability in glutaric aciduria type I: report of fourteen cases in five Canadian Indian kindreds. J Pediatr. 1991;118:52-58.

55 Duhaime AC, Christian C, Armonda R, et al. Disappearing subdural hematomas in children. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1996;25:116-122.

56 Willman KY, Bank DE, Senac M, et al. Restricting the time of injury in fatal inflicted head injuries. Child Abuse Negl. 1997;21:929-940.

57 Kelly JP, Nichols JS, Filley CM, et al. Concussion in sports: guidelines for the prevention of catastrophic outcome. JAMA. 1991;266:2867-2869.

58 Cantu RC. Cerebral concussion in sport: management and prevention. Sports Med. 1992;14:64-74.

59 Cho D, Wang Y, Chi C. Decompressive craniotomy for acute shaken/impact baby syndrome. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1996;23:192-198.

60 Gilles EE, Nelson MDJr. Cerebral complications of nonaccidental head injury in childhood. Pediatr Neurol. 1998;19:119-128.

61 Bonnier C, Nassogne M, Evrard P. Outcome and prognosis of whiplash shaken infant syndrome: late consequences after a symptom-free interval. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1995;37:943-956.

62 Duhaime AC, Christian C, Moss E, et al. Long-term outcome in children with the shaking-impact syndrome. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1996;24:292-298.

63 Haines DE, Harkey HL, Al-Mefty O. The “subdural” space: a new look at an outdated concept. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:111-120.

64 McLone DG, Gutierrez FA. Ultrastructure of subdural membranes of children. Concepts Pediatr Neurosurg. 1989;1:174-187.

65 Parent AD. Pediatric chronic subdural hematoma: a retrospective comparative analysis. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1992;18:266-269.

66 McLaurin RL, Isaacs E, Lewis HP. Results of nonoperative treatment in 15 cases of infantile subdural hematoma. J Neurosurg. 1971;34:753-759.

67 Kooh SW. Metabolic abnormalities of the skull and axial skeleton. In: Hoffman H, Epstein F, editors. Disorders of the Developing Nervous System: Diagnosis and Treatment. Boston: Blackwell Scientific; 1986:449-463.

68 Ingraham FD, Matson DD. Subdural hematoma in infancy. J Pediatr. 1944;24:1-37.

69 Gutierrez FA, McLone DG, Raimondi AJ. Pathophysiology and a new treatment of chronic subdural hematoma in children. Childs Brain. 1979;5:216-232.

70 Duhaime AC, Sutton LN. Delayed sequelae of pediatric head injury. In: Barrow D, editor. Complications and Sequelae of Head Injury. Park Ridge, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 1992:169-186.

71 Aoki N, Masuzawa H. Unilateral subdural-peritoneal shunting for bilateral chronic subdural hematomas in infancy. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:134-137.

72 Aoki N. Chronic subdural hematoma in infancy: clinical analysis of 30 cases in the CT era. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:201-205.

73 Gilles FH, Massoud B, Sotrel A. Infantile atlantooccipital instability. Am J Dis Child. 1979;133:30-37.

74 Bailey DK. The normal cervical spine in infants and children. Radiology. 1952;59:712-719.

75 Sullivan CR, Bruwer AJ, Harris LE. Hypermobility of the cervical spine in children: a pitfall in the diagnosis of cervical dislocation. Am J Surg. 1958;95:636-640.

76 Townsend EH, Rowe ML. Mobility of the upper cervical spine in health and disease. Pediatrics. 1952;10:567-573.

77 Pang D, Pollack IF. Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality in children—the SCIWORA syndrome. J Trauma. 1989;29:654-664.

78 McGrory BF, Fenichel GM. Hangman’s fracture subsequent to shaking in an infant. Ann Neurol. 1977;2:82.

79 Kleinman PK. Spinal trauma. In: Kleinman PK, editor. Diagnostic Imaging of Child Abuse. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1987:91-102.

80 Levin HS, Aldrich EF, Saydjari C, et al. Severe head injury in children: experience of the Traumatic Coma Data Bank. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:435-444.

81 Kriel RL, Krach LE, Panser LA. Closed head injury: comparison of children younger and older than 6 years of age. Pediatr Neurol. 1989;5:296-300.

82 McClelland CQ, Rekate H, Kaufman B, et al. Cerebral injury in child abuse: a changing profile. Childs Brain. 1980;7:225-235.

83 Fischer H, Allasio D. Permanently damaged: long-term followup of shaken babies. Pediatrics. 1994;33:696-698.

84 Han DP, Wilkinson WS. Late ophthalmic manifestations of the shaken baby syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1990;27:299-303.

85 U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. The Abused Child: Principles and Suggested Language for Legislation on Reporting of the Physically Abused Child. Washington, DC: Children’s Bureau, U.S. Government Printing Office; 1963.

86 Faller KC. Unanticipated problems in the United States child protection system. Child Abuse Negl. 1985;9:63-89.

87 Brent R. The irresponsible expert witness: a failure of biomedical education and professional accountability. Pediatrics. 1982;70:754-762.

88 Krugman RD. Advances and retreats in the protection of children. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:531-532.

89 Showers J, Apolo J. Criminal disposition of persons involved in 72 cases of fatal child abuse. Med Sci Law. 1986;26:243-247.

90 Keenan HT, Nocera M, Runyan DK. Race matters in the prosecution of perpetrators of inflicted traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1174-1180.

91 Marx S, Toth P, Dinsmore J. Investigation and Prosecution of Child Abuse, 2nd ed. Alexandria, VA: American Prosecutors Research Institute; 1993.

92 Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989;244:160-166.

93 Martin JA, Elmer E. Battered children grown up: a follow-up study of individuals severely maltreated as children. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16:75-87.

94 Sills JA, Thomas LJ, Rosenbloom L. Non-accidental injury: a two-year study in central Liverpool. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1977;19:26-33.

95 Olds DD, Henderson CR, Chamberlain R. Preventing child abuse and neglect: a randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Pediatrics. 1986;78:65-78.

96 Gray JD, Cutler CA, Dean JG, et al. Prediction and prevention of child abuse. Semin Perinatol. 1979;3:85-90.

97 McCauley K. Preventing child abuse through the schools. Children Today. 1992;21:8-10.

98 Showers J. “Don’t shake the baby”: the effectiveness of a prevention program. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16:11-18.

99 Gray J, Kaplan B, Kempe CH. Eighteen months experience with a lay health visitor program. In Helfer RE, Kempe CH, editors: The Battered Child, 3rd ed, Chicago: University of Chicago, 1980.