Child Abuse

Overview

In the decades since the landmark articles by Caffey (1946) and Kempe and Silverman (1962), the medical community, law enforcement, and Child Protective Services (CPS) have developed a much greater awareness and sensitivity to the diagnosis of child abuse; these groups have not only advocated for protection of the child but have also promoted a more aggressive approach to the identification and prosecution of offending individuals.1,2 Child abuse remains a difficult, emotionally charged topic. The diagnosis of child abuse and the treatment of abused children are intertwined with legal issues of parental rights and family preservation. Because it typically occurs behind closed doors, the abuse is unobserved, and confessions are rare. Presentations are varied, and abuse and neglect may mimic other disease processes.

Etiologies, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Presentation: According to the most recent survey from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in the year 2009 an estimated total of 3,043,000 children were the subject of investigations undertaken by CPS agencies as alleged victims of maltreatment, and approximately 702,000 were found to be victims of maltreatment.3 Thus, in 2009, 40.2 of every 1000 children in the United States were evaluated by CPS for suspected abuse or neglect, and 9.3 of every 1000 children were confirmed by CPS as abused or neglected.3 Of confirmed cases, children were victims of neglect in 78.3%, physical abuse in 17.8%, sexual abuse in 9.5%, psychological maltreatment in 7.6%, and other forms of maltreatment in 9.6% (>100% as many children are victims of multiple forms).3 Young children are at greatest risk for fatality; 81% are younger than 4 years of age at the time of death, and 46% are younger than 1 year of age at death.3 An estimated 1770 children died from abuse or neglect in 2009.3 More than 90% of all confirmed perpetrators have a parental relationship to the victim (mother, father, step-parent, boyfriend or girlfriend of parent).3

Clinical presentations of child abuse are myriad. In some children, abuse is suspected from the start; however, in many, the presentation is cryptic until traumatic findings are made clinically or by imaging.4 Children commonly present with symptoms related to head, abdominal, or extremity trauma. Children may present with bruising, burns, or evidence of neglect. Not infrequently, manifestations of abuse may be found incidentally on imaging performed to evaluate a nontraumatic process. Therefore, the radiologist is occasionally the first to suggest the possibility of child abuse.

Imaging: Initial imaging of the abused child is driven by the clinical presentation.5,6 Imaging is performed to evaluate for processes that need immediate management or may further threaten the child’s well-being if not diagnosed and treated. Once the child’s acute medical issues are addressed and their condition is stable, further imaging in the form of a radiographic skeletal survey can be performed to look for occult injuries and evaluate for child abuse as a diagnosis. The role of such imaging is threefold:

1. Recognition of physical abuse, supporting the diagnosis in suspected cases, and recognizing characteristic lesions when the possibility of child abuse has not been suspected.

2. Provision to the prosecution or defense of accused offenders of an understanding of the mechanism, patterns of healing (dating), and likelihood of such injuries with a reasonable degree of medical certainty.

3. Exclusion of the diagnosis of child abuse in cases of true accidental trauma or with variants of normal and disease processes that may mimic abuse.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used to evaluate suspected head trauma. There are no firm indications for CT of the chest in suspected physical abuse or infants with blunt traumatic injury. CT of the abdomen and pelvis is indicated only in children with physical examination, laboratory findings, or both suggesting traumatic intraabdominal injury.7–9

In all cases of suspected physical abuse in children younger than 2 years of age, a skeletal survey is mandatory (Box 144-1).5,6,10 A “babygram” consisting of single or few images of the entire infant is unsatisfactory. If radiographic film is used, high-detail film without a grid is recommended.10 Digital radiography has replaced film screen skeletal surveys in many centers; however, further evaluation of the technical elements necessary to produce high-detail images is still needed.

Ideally, each skeletal survey is reviewed by a radiologist before the child leaves the radiography suite. Poorly positioned and otherwise suboptimal images should be repeated. Additional views may be obtained to further define positive or suspected abnormalities (e-Fig. 144-1). Commonly acquired additional views include lateral views of the extremities, coned views centered at the joints (wrist, ankle, knee), and Townes view of the skull.

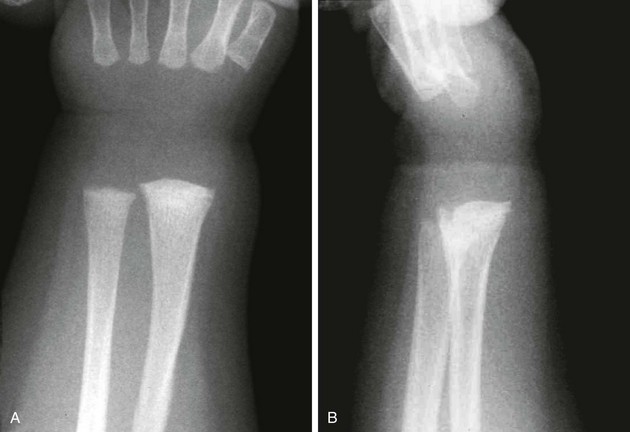

e-Figure 144-1 Images showing the value of additional views in a 2-month-old female infant.

A, Frontal view of the right wrist shows subtle sclerosis and irregularity of the radial metaphysis. B, Lateral view confirms healing classic metaphyseal lesion.

A follow-up skeletal survey performed 2 weeks after the initial examination may provide additional information (e-Fig. 144-2).11,12 As noted by Kleinman, the follow-up survey aids by (1) detecting additional fractures; (2) differentiating fractures from normal developmental variants; and, (3) assisting in dating injuries.11 Follow-up surveys may be limited or tailored to areas of interest.13

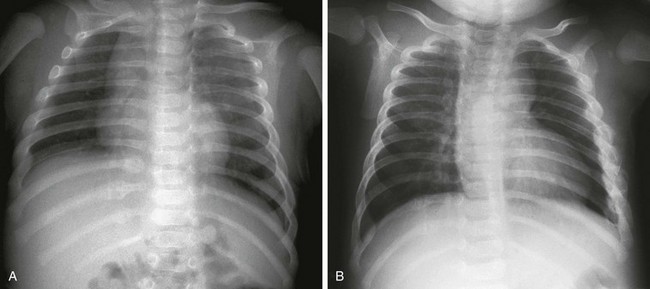

e-Figure 144-2 A 6-week-old male infant sent for an upper gastrointestinal series for evaluation of colicky pain was found to have healing rib fractures.

A, Initial chest radiograph identified healing fractures at the right 9th, 10th, and 11th ribs. B, Follow-up chest radiograph 2 weeks later showed additional fractures, now healing, at the lateral aspect of the left third through ninth ribs. The father admitted to shaking the infant.

In infants and children younger than 2 years, nuclear scintigraphy should be viewed as a complementary modality to radiographic evaluation.14–16 In general, nuclear medicine bone scans are used for problem solving and in children with a high suspicion for abuse but with negative or equivocal radiography.

Whole-body MRI and positron emission tomography have both been studied for the detection of abuse injuries.17,18 Both modalities lack sensitivity for metaphyseal lesions but do detect many abuse-related lesions.

Radiographic skeletal surveys should be performed in all cases of fatal suspected abuse and unexplained infant death.19–22 Postmortem surveys follow the same imaging protocol as used in living infants.20 At present, little experience with postmortem whole body CT exists; however, this technique does show promise for detecting subtle findings to guide the forensic pathologist.23

Imaging Findings: No one radiographic finding is pathognomonic of child abuse. Individual radiographic findings vary from high specificity to low specificity.24,25 High-specificity lesions are seen with abusive trauma but are rarely seen in other forms of trauma. Low-specificity lesions may be commonly seen with abuse-related trauma but are also common with trauma not associated with trauma.

Paul Kleinman has written extensively on the radiography of child abuse and has classified the findings into categories of high, moderate, and low specificities (Box 144-2).24,25 This categorization is supported by many series in the literature, although a number of reports support slight modifications to the categorization of findings.

Rib Fractures

Rib fractures are found in approximately 50% of fatally abused infants.26 The ribs may be the only site of skeletal trauma in some abused children.27 In a surviving infant, the astute clinician may palpate callus with healing or, rarely, crepitus, but otherwise, typically, no physical sign of injury is present. Most acute rib fractures are subtle buckle or greenstick type fractures not evident and frequently are not appreciated on radiography until evidence of healing is found (see e-Fig. 144-2).28 Fracture may occur at any point along the arc of the rib (costovertebral, posterior, lateral, anterior, or costochondral) but frequently involve the posterior rib.26,29 Posterior rib fractures at the costovertebral junction have a high specificity for abuse.30–32 Boal and associates reviewed 1463 rib fractures in 141 abused infants and noted that when individual sites along the rib arc were compared, costovertebral junction fractures outnumbered all other individual sites.30 However, fractures at the costovertebral junction represented only 33% of the total number of rib fractures. Fractures at other sites in the rib arc are very common in abused children, too.30 Fractures at the costochondral junction appear radiographically similar to classic metaphyseal lesions of the long bones and have a high association with visceral trauma.33 First rib fractures bear high specificity for child abuse.34

A squeezing injury, shaking injury, or a combination of both results in leveraging of the posteromedial rib over the spinal transverse process. Excessive compression and distraction forces are also placed on the lateral and anterior rib arc and at the metaphyseal equivalent region near the costovertebral junction of the rib (Fig. 144-3).28,35 Multiple fractures may involve a single rib. Oblique views of the ribs increase the sensitivity for rib fractures and aid in their characterization (Fig. 144-4).36 Nuclear scintigraphy aids in the detection of rib fracture and plays a complementary role to that of radiography (e-Fig. 144-5).14,15 Follow-up radiographs (see e-Fig. 144-2) and CT also provide increased sensitivity.37,38 CT may be more sensitive for rib fractures than radiography, but the greater radiation dose of CT limits its use as a screening modality.37 Nevertheless, focused CT may be helpful in problematic cases. If a CT is performed for evaluation of visceral trauma, reconstruction of images with narrow slice thickness, bone detail algorithm, and multiplanar reformats facilitate identification and delineation of rib fractures (Fig. 144-6).

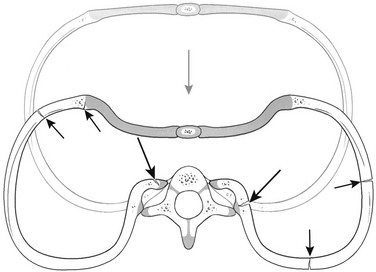

Figure 144-3 Mechanism of rib injury.

With anteroposterior compression (gray arrow) of the chest, excessive leverage of the posterior ribs occurs over the fulcrum of the transverse processes. This places tension along the inner aspects of the rib head and neck regions, resulting in fractures at these sites (long black arrows). This mechanism is consistent with morphologic patterns of injury occurring at other sites along the rib arcs and at the costochondral junctions (short black arrows). (From Kleinman PK. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse. 2nd ed, St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998.)

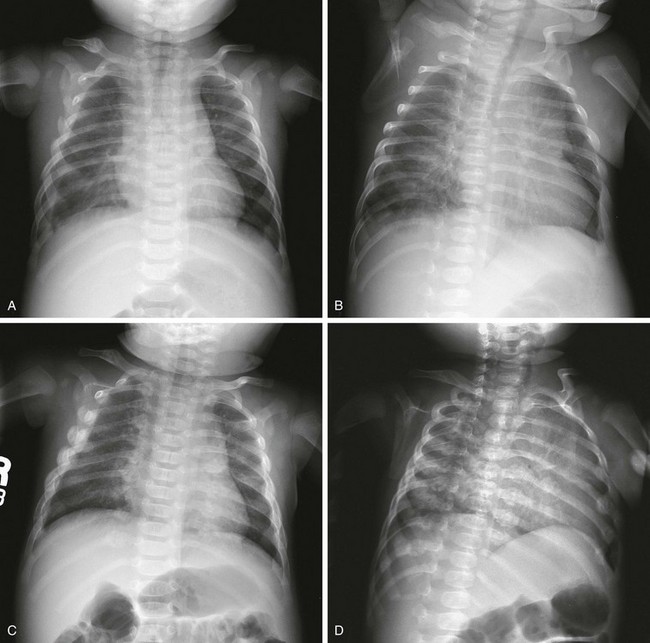

Figure 144-4 A 2-month-old male infant with right pleural effusion.

A, Anteroposterior radiograph shows healing right clavicular fracture and nine fractures of the right ribs and four fractures of the left ribs on initial survey. B, Some fractures are better depicted on the left posterior oblique view. C and D, Two weeks later, anteroposterior and left posterior oblique radiographs of the chest clearly show 18 right rib fractures and 11 left rib fractures, illustrating the value of a follow-up skeletal survey.

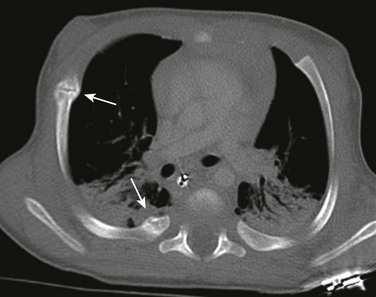

Figure 144-6 A 3-month-old male with multiple rib fractures, multiple metaphyseal fractures (classic metaphyseal lesions), a small subdural hematoma, and disruption of the posterior wall of the hypopharynx.

This computed tomography scanning was performed for concern of extension of infection into the chest. Images were also reconstructed with bone algorithm. Arrows indicate healing posterior and anterolateral rib fractures. The fracture lines are indistinct. Callus is present.

e-Figure 144-5 A 5-week-old male with multiple rib fractures, subdural hematomas, and skull fracture.

Posterior image from bone scintigraphy performed the same day shows multiple bilateral posterior and left lateral rib fractures. The posterior rib fractures are seen as abnormal foci of activity in a line on each side of the spine.

In contrast to adult ribs, fractures rarely occur in infant ribs because of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.39–42 Rare fractures caused by infant cardiopulmonary resuscitation are predominantly anterolateral and are usually radiographically occult.39,40,43 Rib fractures caused by birth trauma are rare.44 A case report noted posteromedial rib fractures from accidental blunt trauma in an infant.45 Rib fractures are commonly seen in infants with metabolic bone disease and have been reported after thoracotomy, chest tube placement, and chest physiotherapy.34,46 However, rib fractures in infants younger than age 12 months without a predisposing condition, for example, instrumentation, prematurity, chronic illness, metabolic bone disease, or all of these, are strongly suspicious for the diagnosis of abuse.34,47

Long Bone Fractures

The classic metaphyseal fracture, first described by Caffey and commonly referred to as a “corner” or “bucket-handle” fracture, was reexamined by Kleinman in 1986 with the use of detailed histopathologic and radiographic studies.1,48 He determined that the lesions represent a complete shearing or planar fracture that extends through the primary spongiosa of the metaphysis and that it is not an avulsion injury as described by Caffey.48,49 Depending on size and displacement of the metaphyseal fragment, the positioning of the child and the radiographic projection, this highly specific lesion caused by abuse may appear as a “corner” fracture or as a “bucket-handle” fracture (Fig. 144-7). Metaphyseal fractures of abuse may also be seen on ultrasonography.50

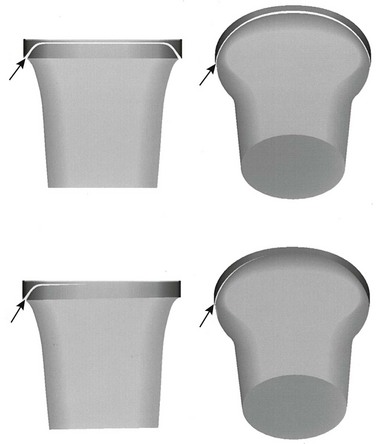

Figure 144-7 Corner and bucket-handle fracture patterns of the classic metaphyseal lesion.

Fractures (arrows) extend adjacent to the chondro-osseous junction and then veer toward the diaphysis to undercut the larger peripheral segment that encompasses the subperiosteal bone collar. When the physis is viewed tangentially, the classic metaphyseal lesion appears as a corner fracture (left images). When a view is obtained through beam angulation, a bucket-handle pattern results (right images). Top images, Diffuse injury; bottom images, localized injury. (From Kleinman PK. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse. 2nd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1998. Originally modified from Kleinman PK, Marks SC, Jr. Relationship of the subperiosteal bone collar to metaphyseal lesions in abused infants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1471-1476.)

The “classic metaphyseal lesion,” a term coined by Kleinman, occurs from violent shaking as the infant is held by the trunk or extremities (Figs. 144-8 and 144-9; e-Fig. 144-10; and Fig. 144-11). Some lesions are probably also caused by torsional pulling on a limb. Typically, no bruising or outward sign of injury is evident with a classic metaphyseal lesion. Classic metaphyseal lesions are most commonly seen at the proximal humerus, distal radius, distal femur, proximal tibia, and distal tibia and fibula.51–54

Figure 144-8 A 2½-month-old male infant with acute and chronic subdural hematoma and 18 fractures.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the right knee shows classic metaphyseal lesions at the distal femur and the proximal tibia.

Figure 144-9 A 1-month-old female infant was brought to the emergency department for swelling of the leg without history of trauma.

A, Anteroposterior view of the left leg. B, Lateral view of the left leg shows classic metaphyseal lesions at the proximal and distal tibia, as well as a short oblique mid-diaphyseal fracture. Multiple rib fractures and classic metaphyseal lesions of the right tibia were also discovered.

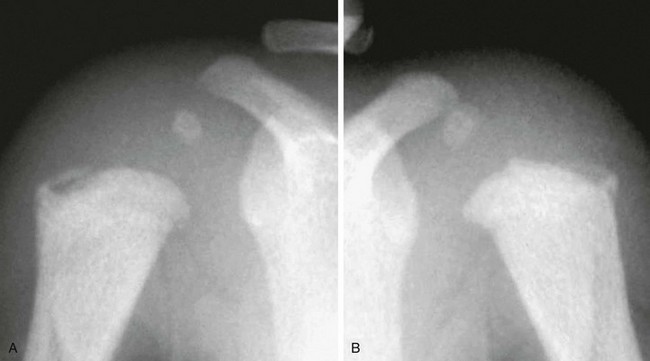

e-Figure 144-10 Anteroposterior right (A) and left (B) shoulders of a 5-month-old female infant, deceased, cause of death unknown.

Eight fractures were identified at postmortem skeletal survey, including bilateral proximal humeral classic metaphyseal lesions.

Occasionally, classic metaphyseal lesions become more conspicuous on short-term follow-up radiography.49 With healing, classic metaphyseal lesions typically become indistinct and sclerotic. Kleinman demonstrated subtle extension of physeal cartilage into the metaphysis as a sign of healing.55 Subperiosteal new bone is not seen unless there is an associated periosteal injury.

Transverse, greenstick, and buckle fractures of the metaphysis may also be caused by child abuse but do not carry the same specificity as the classic metaphyseal lesions. Such fractures are considered to be of low specificity. Small stepoffs, beaks, and spurs at the metaphyseal margins may mimic abusive injury.56 Slight fragmentation of metaphyseal margins with physiologic bowing may also mimic abuse.57 Iatrogenic classic metaphyseal-like lesions have been reported with birth trauma and as a complication of treatment of clubfeet.50,58,59 Such reports are rare and it is likely that the reported fractures occurred with a similar torsional mechanism as occurs in child abuse.

Physeal Fractures

Physeal fractures are uncommon in child abuse. Fractures may be occult or subtle at presentation and some are not recognized until healing occurs.60 Ultrasonography or MRI may be helpful to image the unossified epiphyses and assess the integrity of the physis.61 Common sites of physeal fracture are the proximal humerus (Fig. 144-12), the distal humerus, and the proximal femur.60–62 As opposed to classic metaphyseal lesions, which heal without sequelae, physeal fractures may be complicated by malunion and premature physeal fusion.

Figure 144-12 A 2-year-old girl with delayed diagnosis of a Salter I fracture of the proximal humerus.

The epiphysis (E) is displaced medial relative to the proximal humeral metaphysis. A cloak of early callus and subperiosteal new bone is seen around the proximal humerus (arrows). The child presented with mental status changes caused by a head injury. This fracture and a subtler fracture of the left proximal humerus were noted on chest radiography after intubation. No other fractures were found on a skeletal survey. Follow-up radiographs demonstrated premature fusion of the right proximal humeral physis with marked shortening of humerus noted at age 6 years.

Diaphyseal Fractures

Transverse, oblique and spiral diaphyseal fractures of the long bones in the nonambulatory young infant should raise suspicion for abuse.63–66 Once ambulatory, true accidental fractures become common.67 Solitary long bone fractures may occur after accidental trauma in the older infant and child; however, factors that increase the likelihood of an abuse-related injury include association with another fracture and other clinical features that produce a high level of suspicion for abuse, inappropriate clinical history, failure to seek medical attention, and discovery of the fracture in a healing state (Fig. 144-9; also see Fig. 144-13).66,68,69

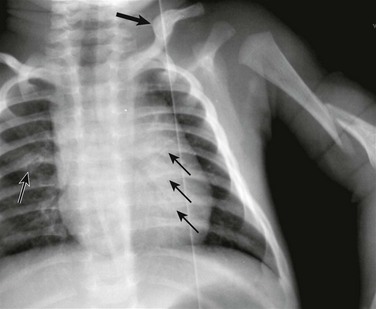

Figure 144-13 A 7-week-old boy with an acute left humeral fracture.

The mechanism provided by history was suspect. Additional imaging demonstrated healing clavicular (large arrow) and posterior rib fractures (small arrows). While it is possible that the healing clavicle fracture is due to unrecognized birth trauma, the healing posterior rib fractures are not compatible with birth injury.

It is risky to assign significance to the pattern of diaphyseal fracture because all patterns occur with unintentional or true accidental trauma as well as with abuse.65,67,70 Particular note is made of the spiral diaphyseal fracture because this fracture has erroneously become synonymous with abuse.65 The spiral nature of the fracture indicates only that torque was a component of the stress applied, which resulted in fracture. The fracture is thought to occur when an infant is grabbed or shaken, with the extremity used as a handle. However, spiral fractures also occur in a child who is ambulatory, and we now know that they may occur accidentally in younger infants. One mechanism was graphically illustrated and reported by Hymel and Jenny: a 5-month-old infant was being videotaped while lying prone and being rolled to a supine position by his 2-year-old sister; an extended upper extremity was unable to adduct and was pinned under the child as he rolled; an oblique humeral diaphyseal fracture was incurred.71 It is important to consider whether the explanation offered and the developmental level of the child are appropriate, also considering the apparent age of the fracture at presentation and whether or not other injuries are apparent.

Fractures of the Scapula and Sternum

Any part of the skeleton may be traumatized from abuse. Although uncommon, fracture of the scapula, in particular the acromion, is highly specific for abuse (e-Fig. 144-14).72 Acromial fracture results from abnormal indirect forces applied during shaking. It is usually accompanied by other bony thoracic trauma. Anatomic variants in the ossification of the acromion may present a diagnostic dilemma.73,74 Follow-up radiographs taken to assess whether or not healing has occurred allow discrimination between fracture and ossification variant.

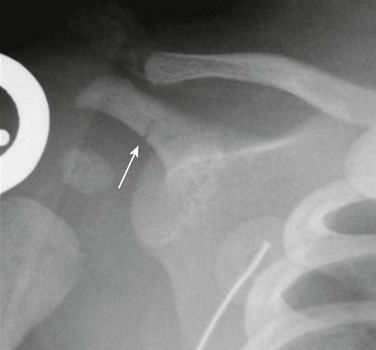

e-Figure 144-14 A 10-week-old girl with fatal abusive head injury.

An acromial fracture (arrow) was the only fracture found by a postmortem skeletal survey.

Fractures of the sternum are very uncommon in infants, including those who are abused.72,75 Although Kleinman classifies sternal fractures as highly specific for child abuse, a recent series found these fractures less specific.75

Clavicle Fractures

Fractures of the clavicle (Fig. 144-15) are common in child abuse but are also common from accidental and birth trauma. Fractures of the clavicle are therefore considered to be of low specificity for child abuse. Clavicle fractures occur in 0.5% of newborns.76 Frequently, a history of dystocia exists. It is not uncommon for such fractures to escape detection on the newborn physical examination.77 Clavicle fractures from birth usually exhibit callus by 10 to 14 days after birth.77 A fracture which appears acute, without visible callus, in a child older than 10 to 14 days therefore becomes suspicious for having been incurred after birth.

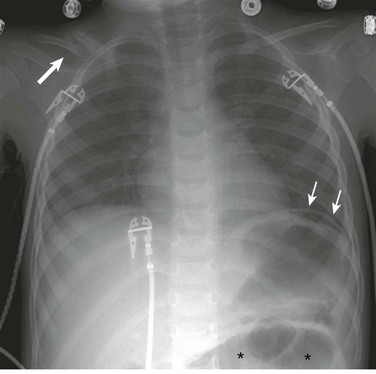

Figure 144-15 A 2-year-old boy with clavicle fracture.

The child presented with fever and vomiting. Multiple bruises were noted. This chest radiograph demonstrated a healing, displaced right clavicle fracture with callus (large arrow), free air underneath the left hemidiaphragm (small arrows), and dilated small bowel in the left abdomen (asterisks). At surgery, multiple small bowel perforations were found.

Spinal Fractures

Although rare, spinal fractures in infants and young children are strongly associated with abuse.72,78–80 The mechanism is thought to be hyperextension, hyperflexion, axial loading, or all. Radiographically, these injuries manifest as compression deformities of the vertebral body, often with associated end plate defects and avulsive injuries of the spinous processes.79 Fractures may result in listhesis.80,81 Injuries often involve multiple adjacent vertebral bodies, most often located near the thoracolumbar junction (Fig. 144-16).78,80

Figure 144-16 A 10-month-old girl with compression fractures of the T12, L1, and L2 vertebral bodies.

She presented with paralysis of the lower extremities, and no history of trauma was initially provided. Unfortunately, the child did not recover lower extremity function.

Cervical spine fractures are fortunately uncommon in child abuse but may be devastating.80 More severe fracture-dislocations have been described, including classic hangman’s fracture of the C2 vertebra (e-Fig. 144-17).82 Although spinal cord injury is uncommon, severe “spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality” has been described in the shaken infant.83,84

e-Figure 144-17 Lateral cervical spine radiograph of a 6-month-old infant who presented with bruising over the left neck.

Although the infant was neurologically intact, 14 fractures, including hangman’s fracture of C2, were identified.

Isolated spinous process fractures are considered highly specific for child abuse.85 Avulsions may be caused by hyperflexion with axial loading or shaking.

Skull Fractures

Skull fractures are frequent in abuse and are indicative of an impact injury. Poor correlation has been shown between the presence of fracture and associated intracranial injury.86,87 Skull fractures also commonly result from true accidental injury. Several authors have tried to characterize specific patterns of injury that occur in abuse, thereby distinguishing abuse skull fractures from true accidental skull fractures. Some agreement has been expressed that multiple fractures, bilateral fractures, diastasis of fractures and sutures, and fractures that cross suture lines are significantly associated with abuse (Fig. 144-18).88–90 However, no particular pattern of skull fracture is diagnostic of abuse.91 Bilateral complex fractures that cross the sagittal suture may result from a single high-impact blow to the midline, and simple linear fractures are seen in abuse and in accidental trauma. One must consider the appropriateness of the history with respect to the type of injury to make the distinction between abuse and accidental trauma. Simple linear skull fractures are considered to be of low specificity for child abuse.24 Such fractures are common in short-distance falls onto a hard surface. Other, more complex skull fractures are not expected from short-distance falls in the home environment and are thus considered to be of moderate specificity.24 Soft tissue swelling is seen with acute fractures; lack of soft tissue swelling suggests that a fracture is not acute.92 Diastatic fractures or widened skull sutures may indicate a space occupying process within the cranium such as diffuse swelling or large subdural hematoma (Fig. 144-19).

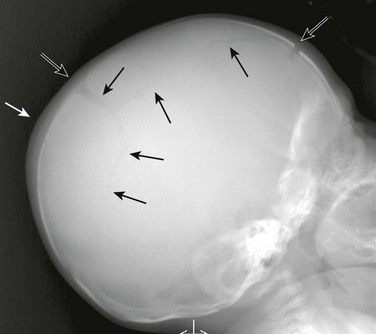

Figure 144-18 A 2-month-old female with complex skull fractures of the involving the right frontal bone and both parietal bones (open and black arrows).

Extracranial soft tissue swelling is noted (white arrow). The child presented to the emergency room with facial bruising. Small bilateral subdural hematomas were found on computed tomography. Multiple healing rib fractures and metaphyseal fractures (classic metaphyseal lesions) were found on skeletal survey.

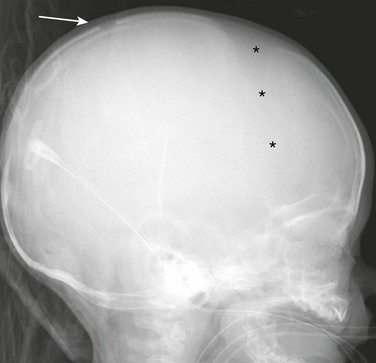

Figure 144-19 A 3-month-old boy with a mildly diastatic parietal skull fracture (arrow) and splayed coronal sutures (asterisks).

Computed tomography showed large bilateral subdural hematomas.

Anteroposterior and lateral skull radiographs are part of the radiographic skeletal survey in suspected abuse, and additional views may be necessary. A Townes view is helpful to evaluate the occipital bone and look for wormian bones in the sutures. Wormian bones are accessory intrasutural bones associated with metabolic bone disease, most notably osteogenesis imperfecta and Menke syndrome.93 CT alone is inadequate to assess for skull fractures because fractures in the axial plane may be difficult to detect. CT may be indicated to evaluate for suspected intracranial injury; bone window images should be evaluated for signs of skull and other fractures; extracranial soft tissue swelling is also well delineated.

Accessory sutures of the skull may mimic fractures on both radiography and CT. Findings suggesting a fracture are a sharp linear lucency with nonsclerotic edges, widening of the lucency approaching a suture, crossing of a suture, unilaterality or asymmetry, and associated soft tissue swelling.94 Findings suggesting an accessory suture are a zigzag pattern with sclerotic borders merging with an adjacent suture, bilaterality and symmetry, and lack of associated soft tissue swelling.94 Accessory sutures tend to occur at characteristic locations.

Fractures of the Pelvis

Fractures of the pelvic bones are uncommon in child abuse (Fig. 144-20).95 Fractures of the pubic rami may occur from blunt trauma, particularly in cases of sexual abuse.96 Variants in pubic ossification may mimic fracture.97

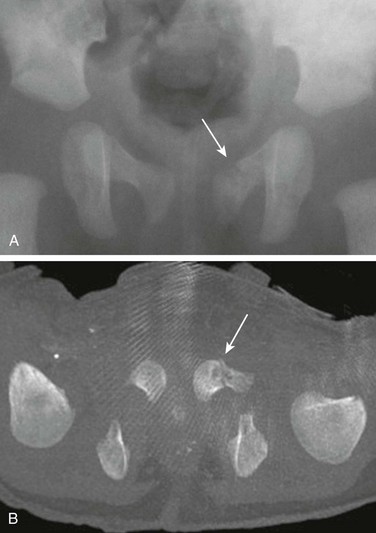

Figure 144-20 A 1-month-old boy presented with failure to thrive and fever.

A fracture of the left superior pubic symphysis (arrows) is seen on radiography (A) and axial bone algorithm computed tomographic (CT) image (B), reformatted from a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate for suspected visceral injury. He was also found to have subdural hematomas and healing rib fractures.

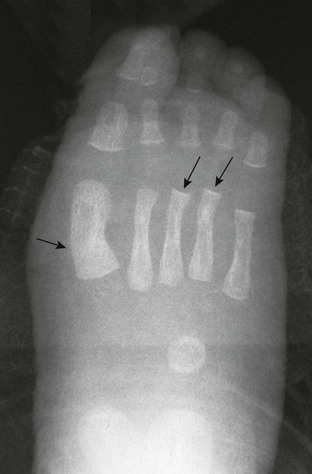

Fractures of Hands and Feet

Nonaccidental fractures of the hands and feet occur in abused infants and toddlers (Fig. 144-21).98 These fractures are often subtle torus fractures and may be better appreciated on oblique views or follow-up radiographs.98 Fractures of the tubular bones of the hands and feet are probably caused by squeezing by the hands of the abuser.

Dating of Fractures

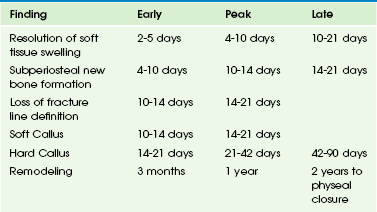

Dating of fractures is dependent on many variables, including the age of the child, the state of nutrition, immobilization or lack thereof, repetitive injury, and fracture location.99,100 Fractures of the skull and spine cannot be satisfactorily dated, and the classic metaphyseal lesion is difficult to date with any degree of precision.

In general, a young infant develops subperiosteal new bone much earlier and forms callus more quickly. The range for the appearance of subperiosteal new bone is 4 days to several weeks.100 Soft tissue swelling resolves during this same period with subsequent loss of fracture line definition and the appearance of soft callus followed by hard callus. Although it is often possible to identify separate fractures as acute or subacute and others as healing, it is very difficult is ascribe different ages to fractures which are healing. Remodeling of fractures occurs over a span of months to years. Precise dating of fractures is not possible and speculation of fracture age is merely an estimate. Some general guidelines are provided in Table 144-1 (Fig. 144-22).99,100

Table 144-1

Timetable of Radiographic Changes in Children’s Fractures*

*Repetitive injuries may prolong the presence of findings.

From Kleinman PK. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse. 2nd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1998.

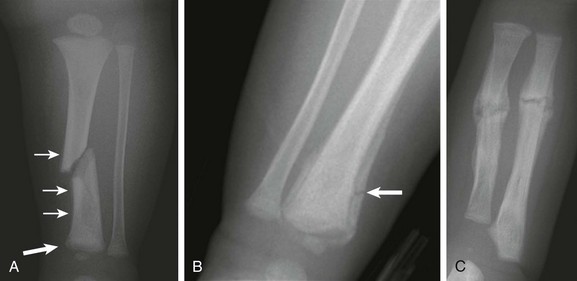

Figure 144-22 A 3-month old boy with multiple fractures of differing age.

The child presented with left leg swelling. A, Radiograph of the left leg shows an acute or subacute oblique fracture of the left tibia. No ossified callus is seen; however, subperiosteal new bone (arrows) is present along the medial margin of the distal tibial, possibly unrelated to the oblique fracture. Irregularity of the distal metaphysis is suggestive of a preceding classic metaphyseal lesion, but not definitive. Soft tissue swelling is noted. B, Radiograph of the distal right leg shows a healing bucket handle fracture with associated distal tibial subperiosteal new bone indicative of an injury at least 10 to 14 days old. A fracture through the subperiosteal new bone (arrow) indicates injuries of different age. C, Transverse fractures of the left radius and ulna show a more advanced state of healing with abundant callus and indistinct, partially obliterated fracture lines. These fractures are clearly older than the oblique left tibial fracture. Images of the ribs showed multiple healing lateral and posterior rib fractures with mature callus.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for child abuse is broad and varies considerably, depending on both the clinical presentation and the radiologic findings (Box 144-3).101,102 True accidental injury is not the only consideration. Unrecognized obstetric trauma may not be noted until days or weeks after birth. Normal processes including metaphyseal variants, physiologic new bone formation, accessory ossification centers, and accessory skull sutures may initially suggest an abuse-related lesion.103,104 Iatrogenic injury may mimic abuse-related injury.42,44,46,58,59,105

Metabolic bone disease of prematurity may result in multiple rib fractures, diaphyseal fractures, and metaphyseal fractures.106–108 Such fractures are typically buckle or transverse fractures, not classic metaphyseal lesions. Other disease processes, including inherited bone dysplasias, copper deficiency (Menke syndrome), congenital syphilis, Caffey disease, neurologic disorders, and osteogenesis imperfecta may have radiographic features that overlap with those of abuse (see Box 144-3).101,102,109–113 Most of these disorders are discussed individually in this text. Underlying fragility of the bones may, in turn, predispose some children to iatrogenic injury, which may mimic abuse.

Metaphyseal abnormalities similar to child abuse are seen with some rare skeletal dysplasias, notably spondylometaphyseal dysplasia, Sutcliffe (“corner fracture”) type, and metaphyseal dysplasia, Schmid type.114,115 In such patients, findings may be asymmetric. Clues as to the presence of a dysplasia include family history, short stature, and lack of change of the findings on follow-up radiographs.

Kleinman’s seminal text Diagnostic Imaging of Child Abuse presents an excellent overview of the differential diagnosis and a review of diseases that simulate abuse.24 Fortunately, it is almost always possible to make an accurate determination as to the presence or absence of genetic disease on the basis of clinical and radiographic examination, along with a review of family and social history. It should be remembered that the presence of an underlying bone disease or dysplasia does not exclude the possibility of physical abuse or neglect.

TBBD was proposed as a variant of osteogenesis imperfecta by Paterson and colleagues, who identified a group of young infants who were thought to have diminished bone strength, possibly because of temporary deficiency of a metalloenzyme related to copper deficiency.116 Evidence provided to support the existence of TBBD included denial by caregivers of wrongdoing, absence of episodes of trauma that may explain fractures, lack of bruising, absence of systemic injury, radiographs revealing normal bones, and normal laboratory studies.116 The purported evidence and the particular diagnosis of TBBD has been refuted by others, including the authors of a critical review of TBBD prepared by the Committee on Child Abuse of the Society for Pediatric Radiology.113,117,118 To date, no scientific proof definitively supports the existence of TBBD.

More recently, fractures consistent with abuse have been ascribed to vitamin D deficiency by some authors.119 While literature supports a high prevalence of infants with low vitamin D levels, the authors did not provide evidence of predisposing low vitamin D levels in their patients or convincing evidence as to the causation of the fractures related to low vitamin D levels.120 Currently, no evidence exists in the literature to support low levels of vitamin D predisposing children to the high-specificity lesions characteristic of child abuse.121 It is true, however, that infants and young children with frank rickets caused by vitamin D deficiency are at risk for fracture; however, the pattern of such fractures differs from the high-specificity classic metaphyseal lesions and posterior rib fractures seen with abuse.122

Treatment: Treatment of the individual patient with abuse-related injuries is dictated by the injuries that are present. Injuries to the brain, spinal cord, and viscera may be life threatening. Brain and spinal cord injuries may cause substantial lifelong morbidity. Treatment is aimed at preserving the life of the child and limiting permanent morbidity. Fortunately, most skeletal injuries heal without permanent sequelae, with fractures of the growth plate being an occasional exception.

Intracranial trauma is the leading cause of death and permanent morbidity in abused infants. It has been nearly 40 years since Caffey proposed his theory on the shaking of infants.123 In contrast to true accidental head injury, the neurologic deficits that occur in shaken baby syndrome are out of proportion to the degree of physical trauma and to the changes evident on CT and MRI. Debate is ongoing about whether or not shaking alone is sufficient to result in brain injury or whether an impact injury must accompany the shaking event.124 Apnea and cerebral hypoxia also play a role.

Infants with shaken baby syndrome commonly have subdural hematomas, retinal hemorrhages, and characteristic skeletal injuries (posterior rib fractures and classic metaphyseal lesions). The presence of these osseous lesions is an indication for brain imaging (CT, if emergently indicated; MRI, for more detailed evaluation) and for ophthalmologic evaluation of the eyes for retinal hemorrhage. Retinal hemorrhages are present in 80% to 85% of shaken babies.125

Carty, H. Non-accidental injury: a review of the radiology. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:1365–1376.

Dwek, JR. The radiographic approach to child abuse. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:776–789.

Kleinman, PK. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse, 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998.

Lonergan, GJ, Baker, AM, Morey, MK, et al. From the archives of the AFIP. Child abuse: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23:811–845.

Offiah, A, van Rijn, RR, Perez-Rossello, JM, et al. Skeletal imaging of child abuse (non-accidental injury). Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:461–470.

References

1. Caffey, J. Multiple fractures in the long bones of infants suffering from chronic subdural hematoma. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther. 1946;56:163–173.

2. Kempe, CH, Silverman, FN, Steele, BF, et al. The battered child syndrome. JAMA. 1962;181:17–24.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Familes, Children’s Bureau (2010). Child Maltreatment 2009. Washington, D.C.: U.S. government Printing Office; 2011.

4. Ravichandiran, N, Schuh, S, Bejuk, M, et al. Delayed identification of pediatric abuse-related fractures. Pediatrics. 2010;125:60–66.

5. Meyer, JS, Gunderman, R, Coley, BD, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® on suspected physical abuse-child. J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8:87–94.

6. Section on Radiology, American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1430–1435.

7. Trout, AT, Strouse, PJ, Mohr, BA, et al. Abdominal and pelvic CT in cases of suspected abuse: can clinical and laboratory findings guide its use? Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:92–98.

8. Lindberg, D, Makoroff, K, Harper, N, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases to recognize abuse in children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:509–516.

9. Hilmes, MA, Hernanz-Schulman, M, Greeley, CS, et al. CT identification of abdominal injuries in abused pre-school children. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:643–651.

10. American College of Radiology. ACR-SPR practice guideline for skeletal surveys in children. http://www.acr.org, 2011. [Accessed October 23, 2011].

11. Kleinman, PK, Nimkin, K, Spevak, MR, et al. Follow-up skeletal surveys in suspected child abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:893–896.

12. Zimmerman, S, Makoroff, K, Care, M, et al. Utility of follow-up skeletal surveys in suspected child physical abuse evaluations. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:1075–1083.

13. Harlan, SR, Nixon, GW, Campbell, KA, et al. Follow-up skeletal surveys for nonaccidental trauma: can a more limited survey be performed? Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:962–968.

14. Conway, JJ, Collins, M, Tanz, RR, et al. The role of bone scintigraphy in detecting child abuse. Semin Nucl Med. 1993;23:321–333.

15. Sty, JR, Starshak, RJ. The role of bone scintigraphy in the evaluation of the suspected abused child. Radiology. 1983;146:369–375.

16. Mandelstam, SA, Cook, D, Fitzgerald, M, et al. Complementary use of radiological skeletal survey and bone scintigraphy in detection of bony injuries in suspected child abuse. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:387–390.

17. Perez-Rossello, JM, Connolly, SA, Newton, AW, et al. Whole-body MRI in suspected infant abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:744–750.

18. Drubach, LA, Johnston, PR, Newton, AW, et al. Skeletal trauma in child abuse: detection with 18F-NaF PET. Radiology. 2010;255:173–181.

19. McGraw, EP, Pless, JE, Pennington, DJ, et al. Postmortem radiography after unexpected death in neonates, infants, and children: should imaging be routine? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1517–1521.

20. The Society for Pediatric Radiology—National Association of Medical Examiners. Post-mortem radiography in the evaluation of unexpected death in children less than 2 years of age whose death is suspicious for fatal abuse. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:675–677.

21. McGraw, EP, Pless, JE, Pennington, DJ, et al. Postmortem radiography after unexpected death in neonates, infants and children: should imaging be routine? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1517–1521.

22. Kleinman, PK, Blackbourne, BD, Marks, SC, et al. Radiologic contributions to the investigation and prosecution of cases of fatal infant abuse. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1045–1046.

23. Hong, TS, Reyes, JA, Moineddin, R, et al. Value of postmortem thoracic CT over radiography in imaging of pediatric rib fractures. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:736–748.

24. Kleinman, PK. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse, 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998.

25. Kleinman, PK. Diagnostic imaging in infant abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:703–712.

26. Kleinman, PK, Marks, SC, Nimkin, K, et al. Rib fractures in 31 abused infants: postmortem radiologic-histopathologic study. Radiology. 1996;200:807–810.

27. Barsness, KA, Cha, ES, Bensard, DD, et al. The positive predictive value of rib fractures as an indicator of nonaccidental trauma in children. J Trauma. 2003;54:1107–1110.

28. Kleinman, PK, Marks, SC, Adams, VI, et al. Factors affecting visualization of posterior rib fractures in abused infants. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:635–638.

29. Worn, MJ, Jones, MD. Rib fractures in infancy: establishing the mechanisms of cause from the injuries—a literature review. Med Sci Law. 2007;47:200–212.

30. Boal, DK, Felman, AH, Krugman, RD. Controversial aspects of child abuse: a roundtable discussion. 43rd annual meeting, Society for Pediatric Radiology. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:760–774.

31. Merten, DF, Radkowski, MA, Leonidas, JC. The abused child: a radiological reappraisal. Radiology. 1983;46:377–381.

32. Thomas, PS. Rib fractures in infancy. Ann Radiol. 1977;20:115–122.

33. Ng, CS, Hall, CM. Costochondral junction fractures and intra-abdominal trauma in non-accidental injury (child abuse). Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28:671–676.

34. Strouse, PJ, Owings, CL. Fractures of the first rib in child abuse. Radiology. 1995;197:763–765.

35. Kleinman, PK, Schlesinger, AE. Mechanical factors associated with posterior rib fractures: laboratory and case studies. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:87–91.

36. Ingram, J, Connell, J, Hay, T, et al. Oblique radiographs of the chest in nonaccidental trauma. Emerg Radiol. 2000;7:42–46.

37. Wootton-Gorges, SL, Stein-Wexler, R, Walton, JW, et al. Comparison of computed tomography and chest radiography in the detection of rib fractures in abused infants. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:659–663.

38. Anilkumar, A, Fender, LJ, Broderick, NJ, et al. The role of the follow-up chest radiograph in suspected non-accidental injury. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:216–218.

39. Maguire, S, Mann, M, John, N, et al. Does cardiopulmonary resuscitation cause rib fractures in children? A systematic review. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:739–751.

40. Betz, P, Liebhardt, E. Rib fractures in children—resuscitation or child abuse? Int J Legal Med. 1994;106:215–218.

41. Feldman, KW, Brewer, KD. Child abuse, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and rib fractures. Pediatrics. 1984;73:339–342.

42. Spevak, MR, Kleinman, PK, Belanger, PL, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and rib fractures in infants. A postmortem radiologic-pathologic study. JAMA. 1994;272:617–618.

43. Matshes, EW, Lew, EO. Two-handed cardiopulmonary resuscitation can cause rib fractures in infants. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2010;31:303–307.

44. van Rijn, RR, Bilo, RA, Robben, SG. Birth-related mid-posterior rib fractures in neonates: a report of three cases (and a possible fourth case) and a review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:30–34.

45. Bixby, SD, Abo, A, Kleinman, PK. High-impact trauma causing multiple posteromedial rib fractures in a child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:218–219.

46. Chalumeau, M, Foix-l’Helias, L, Scheinmann, P, et al. Rib fractures after chest physiotherapy for bronchiolitis or pneumonia in infants. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:644–647.

47. Cadzow, SP, Armstrong, KL. Rib fractures in infants: red alert! The clinical features, investigations and child protection outcomes. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000;36:322–326.

48. Kleinman, PK, Marks, SC, Blackbourne, B. The metaphyseal lesion in abused infants: a radiologic-histopathologic study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:895–905.

49. Kleinman, PK, Marks, SC, Jr. Relationship of the subperiosteal bone collar to metaphyseal lesions in abused infants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1471–1476.

50. Markowitz, RI, Hubbard, AM, Harty, MP, et al. Sonography of the knee in normal and abused infants. Pediatr Radiol. 1993;23:264–267.

51. Kleinman, PK, Marks, SC, Jr. A regional approach to the classic metaphyseal lesion in abused infants: the proximal humerus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1399–1403.

52. Kleinman, PK, Marks, SC, Jr. A regional approach to the classic metaphyseal lesion in abused infants: the distal femur. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:43–47.

53. Kleinman, PK, Marks, SC, Jr. A regional approach to the classic metaphyseal lesion in abused infants: the proximal tibia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:421–426.

54. Kleinman, PK, Marks, SC, Jr. A regional approach to classic metaphyseal lesions in abused infants: the distal tibia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:1207–1212.

55. Kleinman, PK, Marks, SC, Jr., Spevak, MR, et al. Extension of growth-plate cartilage into the metaphysis: a sign of healing fracture in abused infants. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:775–779.

56. Kleinman, PK, Belanger, PL, Karellas, A, et al. Normal metaphyseal radiologic variants not to be confused with findings of infant abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:781–783.

57. Kleinman, PK, Sarwar, ZU, Newton, AW, et al. Metaphyseal fragmentation with physiologic bowing: a finding not to be confused with the classic metaphyseal lesion. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1266–1268.

58. O’Connell, A, Donoghue, VB. Can classic metaphyseal lesions follow uncomplicated caesarean section? Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:488–491.

59. Grayev, AM, Boal, DK, Wallach, DM, et al. Metaphyseal fractures mimicking abuse during treatment for clubfoot. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:559–563.

60. Merten, DF, Kirks, DR, Ruderman, RJ. Occult humeral epiphyseal fracture in battered infants. Pediatr Radiol. 1981;10:151–154.

61. Nimkin, K, Kleinman, PK, Teeger, S, et al. Distal humeral physeal injuries in child abuse: MR imaging and ultrasonography findings. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25:562–565.

62. Jones, JC, Feldman, KW, Bruckner, JD. Child abuse in infants with proximal physeal injuries of the femur. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:157–161.

63. Strait, RT, Siegel, RM, Shapiro, RA. Humeral fractures without obvious etiologies in children less than 3 years of age: when is it abuse? Pediatrics. 1995;96:667–671.

64. Anderson, WA. The significance of femoral fractures in children. Ann Emerg Med. 1982;11:174–177.

65. Scherl, SA, Miller, L, Lively, N, et al. Accidental and nonaccidental femur fractures in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000:96–105.

66. Pandya, NK, Baldwin, KD, Wolfgruber, H, et al. Humerus fractures in the pediatric population: an algorithm to identify abuse. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19:535–541.

67. Schwend, RM, Werth, C, Johnston, A. Femur shaft fractures in toddlers and young children: rarely from child abuse. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:475–481.

68. Pierce, MC, Bertocci, GE, Vogeley, E, et al. Evaluating long bone fractures in children: a biomechanical approach with illustrative cases. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:505–524.

69. Baldwin, K, Pandya, NK, Wolfgruber, H, et al. Femur fractures in the pediatric population: abuse or accidental trauma? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:798–804.

70. Blakemore, LC, Loder, RT, Hensinger, RN. Role of intentional abuse in children 1 to 5 years old with isolated femoral shaft fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:585–588.

71. Hymel, KP. Abusive spiral fractures of the humerus: a videotaped exception. Arch Dis Child. 1996;150:226–227.

72. Kogutt, MS, Swischuk, LE, Fagan, CJ. Patterns of injury and significance of uncommon fractures in the battered child syndrome. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1974;121:143–149.

73. Currarino, G, Prescott, P. Fractures of the acromion in young children and a description of a variant in acromial ossification which may mimic a fracture. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24:251–255.

74. Kleinman, PK, Spevak, MR. Variations in acromial ossification simulating infant abuse in victims of sudden infant death syndrome. Radiology. 1991;180:185–187.

75. Hechter, S, Huyer, D, Manson, D. Sternal fractures as a manifestation of abusive injury in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:902–906.

76. McBride, MT, Hennrikus, WL, Mologne, TS. Newborn clavicle fractures. Orthopedics. 1998;21:317–319.

77. Cumming, WA. Neonatal skeletal fractures. Birth trauma or child abuse? J Can Assoc Radiol. 1979;30:30–33.

78. Swischuk, LE. Spine and spinal cord trauma in the battered child syndrome. Radiology. 1969;92:733–738.

79. Kleinman, PK, Marks, SC. Vertebral body fractures in child abuse. Radiologic-histopathologic correlates. Invest Radiol. 1992;27:715–722.

80. Kemp, AM, Joshi, AH, Mann, M, et al. What are the clinical and radiological characteristics of spinal injuries from physical abuse: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:355–360.

81. Levin, TL, Berdon, WE, Cassell, I, et al. Thoracolumbar fracture with listhesis—an uncommon manifestation of child abuse. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:305–310.

82. Kleinman, PK, Shelton, YA. Hangman’s fracture in an abused infant: imaging features. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:776–777.

83. Brown, RL, Brunn, MA, Garcia, VF. Cervical spine injuries in children: a review of 103 patients treated consecutively at a level 1 pediatric trauma center. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1107–1114.

84. Feldman, KW, Avellino, AM, Sugar, NF, et al. Cervical spinal cord injury in abused children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:222–227.

85. Kleinman, PK, Zito, JL. Avulsion of the spinous processes caused by infant abuse. Radiology. 1984;151:389–391.

86. Mogbo, KI, Slovis, TL, Canady, AI, et al. Appropriate imaging in children with skull fractures and suspicion of abuse. Radiology. 1998;208:521–524.

87. Erlichman, DB, Blumfield, E, Rajpathak, S, et al. Association between linear skull fractures and intracranial hemorrhage in children with minor head trauma. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1375–1379.

88. Fernando, S, Obaldo, RE, Walsh, IR, et al. Neuroimaging of nonaccidental head trauma: pitfalls and controversies. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:827–838.

89. Meservy, CJ, Towbin, R, McLaurin, RL, et al. Radiographic characteristics of skull fractures resulting from child abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:173–175.

90. Hobbs, CJ. Skull fracture and the diagnosis of abuse. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:246–252.

91. Kemp, AM, Dunstan, F, Harrison, S, et al. Patterns of skeletal fractures in child abuse: systematic review. Br Med J. 337, 2008. [a1518.doi:10.1136/bmj.a1518].

92. Kleinman, PK, Spevak, MR. Soft tissue swelling and acute skull fractures. J Pediatr. 1992;121:737–739.

93. Cremin, B, Goodman, H, Spranger, J, et al. Wormian bones in osteogenesis imperfecta and other disorders. Skeletal Radiol. 1982;8:35–38.

94. Sanchez, T, Stewart, D, Walvick, M, et al. Skull fracture vs. accessory sutures: how can we tell the difference? Emerg Radiol. 2010;17:413–418.

95. Ablin, DS, Greenspan, A, Reinhart, MA. Pelvic injuries in child abuse. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:454–457.

96. Johnson, K, Chapman, S, Hall, CM. Skeletal injuries associated with sexual abuse. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:620–623.

97. Perez-Rossello, JM, Connolly, SA, Newton, AW, et al. Pubic ramus radiolucencies in infants: the good, the bad and the indeterminate. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1481–1486.

98. Nimkin, K, Spevak, MR, Kleinman, PK. Fractures of the hands and feet in child abuse: imaging and pathologic features. Radiology. 1997;203:233–236.

99. Prosser, I, Maguire, S, Harrison, SK, et al. How old is this fracture? Radiologic dating of fractures in children: a systematic review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1282–1286.

100. O’Connor, J, Cohen, J. Dating fractures. In: Kleinman PK, ed. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:168–177.

101. Swischuk, L. Not everything is child abuse. Emerg Radiol. 2000;7:218–224.

102. Radkowski, MA. The battered child syndrome: pitfalls in radiological diagnosis. Pediatr Ann. 1983;12:894–903.

103. Shopfner, CE. Periosteal bone growth in normal infants. A preliminary report. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1966;97:154–163.

104. Kwon, DS, Spevak, MR, Fletcher, K, et al. Physiologic subperiosteal new bone formation: prevalence, distribution, and thickness in neonates and infants. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:985–988.

105. Harty, MP, Kao, SC. Intraosseous vascular access defect: Fracture mimic in the skeletal survey for child abuse. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:188–190.

106. Dabezies, EJ, Warren, PD. Fractures in very low birth weight infants with rickets. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;335:233–239.

107. Amir, J, Katz, K, Grunebaum, M, et al. Fractures in premature infants. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988;8:41–44.

108. Carroll, DM, Doria, AS, Babyn, PS. Clinical-radiological features of fractures in premature infants—a review. J Perinat Med. 2007;35:366–375.

109. Lim, HK, Smith, WL, Sato, Y, et al. Congenital syphilis mimicking child abuse. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25:560–561.

110. Bacopoulou, F, Henderson, L, Philip, SG. Menkes disease mimicking non-accidental injury. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:919.

111. Kleinman, PK. Problems in the diagnosis of metaphyseal fractures. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(suppl 3):S388–S394.

112. Ablin, DS, Greenspan, A, Reinhart, M, et al. Differentiation of child abuse from osteogenesis imperfecta. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:1035–1046.

113. Chapman, S, Hall, CM. Non-accidental injury or brittle bones. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:106–110.

114. Kleinman, PK. Schmid-like metaphyseal chondrodysplasia simulating child abuse. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:576–578.

115. Kozlowski, K, Robben, S, Bellemore, M, et al. Spondylo-metaphyseal dysplasia corner fracture type a cautionary tale. Radiol Med. 1993;85:7–11.

116. Paterson, CR, Burns, J, McAllion, SJ. Osteogenesis imperfecta: the distinction from child abuse and the recognition of a variant form. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:187–192.

117. Mendelson, KL. Critical review of temporary brittle bone disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:1036–1040.

118. Ablin, DS, Sane, SM. Non-accidental injury: confusion with temporary brittle bone disease and mild osteogenesis imperfecta. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:111–113.

119. Keller, KA, Barnes, PD. Rickets vs. abuse: a national and international epidemic. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:1210–1216.

120. Slovis, TL, Chapman, S. Evaluating the data concerning vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency and child abuse. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:1221–1224.

121. Schilling, S, Wood, JN, Levine, MA, et al. Vitamin D status in abused and nonabused children younger than 2 years old with fractures. Pediatrics. 2011;127:835–841.

122. Chapman, T, Sugar, N, Done, S, et al. Fractures in infants and toddlers with rickets. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1184–1189.

123. Caffey, J. On the theory and practice of shaking infants. Its potential residual effects on permanent brain damage and mental retardation. Am J Dis Child. 1972;124:161–169.

124. Cory, CZ, Jones, BM. Can shaking alone cause fatal brain injury? A biomechanical assessment of the Duhaime shaken baby syndrome model. Med Sci Law. 2003;43:317–333.

125. Levin, AV. Retinal hemorrhage in abusive head trauma. Pediatrics. 2010;126:961–970.