CHAPTER 2 Chest Trauma

INJURIES OF THE PLEURAL SPACE

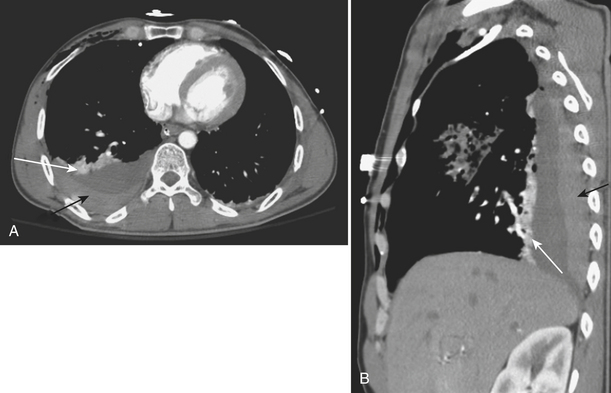

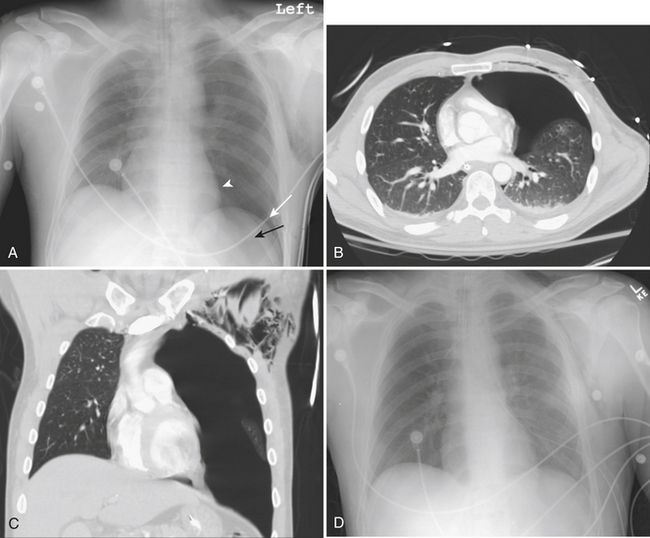

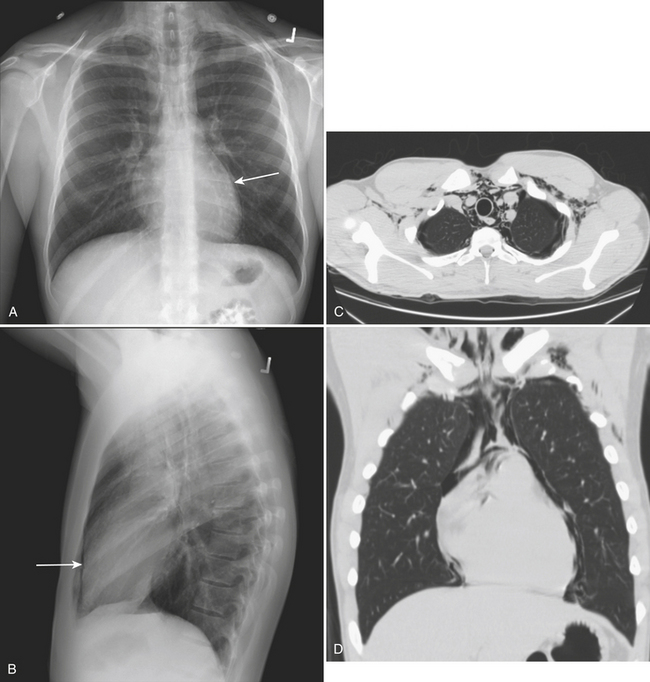

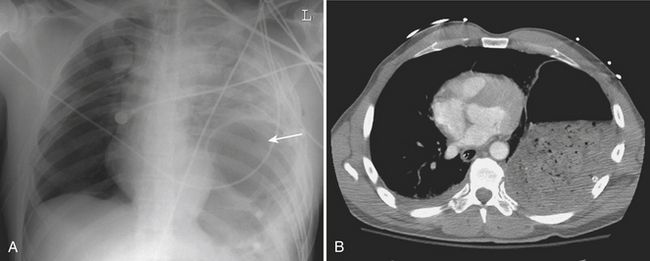

A hemothorax, blood in the pleural space, may result from injury to the chest wall, diaphragm, lung, or mediastinal structures. CT may confirm a hemothorax when a pleural fluid collection in a trauma patient seen on CT measures blood density over 35 to 40 Hounsfield units (HU) (Fig. 2-1). A pneumothorax, air in the pleural space, may result from a lung injury, tracheobronchial injury, or esophageal rupture. The most common cause is lung injury associated with a rib fracture. A pneumothorax occurs in about 15% to 40% of patients with acute chest trauma. Many small and even moderate-sized pneumothoraces that are not visible on the supine chest film may be identified on CT. A pneumothorax seen on CT that cannot be identified on a supine chest film is referred to as an “occult” pneumothorax. Studies estimate that 10% to 50% of pneumothoraces seen on CT are not evident on the supine anteroposterior film. Radiographic signs of pneumothorax may be subtle. In the supine patient air collects in nondependent locations such as the anterior costophrenic sulcus. This region extends from the seventh costal cartilage to the eleventh rib in the midaxillary line. The air collection appears as an abnormal lucency in the lower chest or upper abdomen, frequently referred to as the “deep sulcus” sign. Additional signs of pneumothorax in a supine patient include a sharply outlined cardiac or diaphragmatic border and depression of the hemidiaphragm (Fig. 2-2). Detection of even a small pneumothorax is important as it may enlarge during positive-pressure ventilation or general anesthesia. A tension pneumothorax is an emergency condition resulting from a lung or airway injury associated with a one-way accumulation of air within the pleural space. As intrapleural pressure rises the mediastinal structures are compressed, decreasing venous return to the heart, leading to hemodynamic instability. Radiography and CT will show mediastinal shift to the contralateral hemithorax, hyperexpansion of the ipsilateral thorax, and depression of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm.

CARDIAC INJURIES

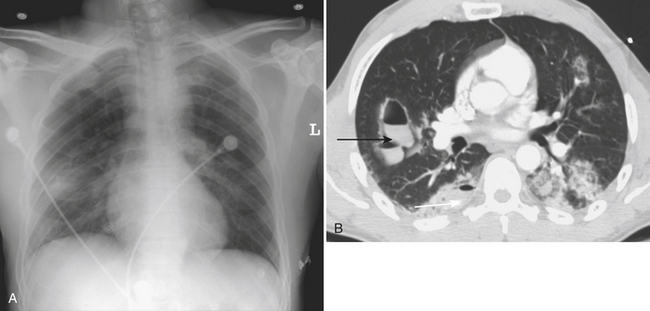

Cardiac and pericardial injuries are uncommon with blunt thoracic trauma but do occur with severe blows to the anterior chest. The diagnosis of blunt cardiac injury relies on a high clinical suspicion. Cardiac injuries often occur in conjunction with sternal fractures. The anterior aspect of the heart that abuts the sternum is most vulnerable to injury. Patients with cardiac injuries may have an abnormal electrocardiogram and elevated cardiac enzymes. Cardiac injuries include cardiac contusion, cardiac rupture, pneumopericardium, hemopericardium, cardiac tamponade, and cardiac valve injury. Hemopericardium from a cardiac injury or cardiac rupture may quickly produce cardiac tamponade with hemodynamic compromise (Fig. 2-3). Cardiomegaly may be seen on the plain chest radiograph, while CT or cardiac sonography may confirm hemopericardium.

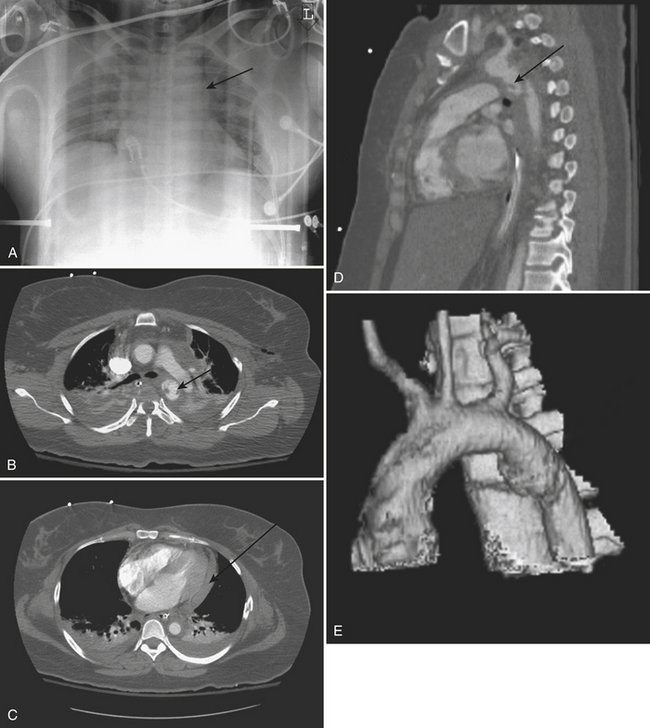

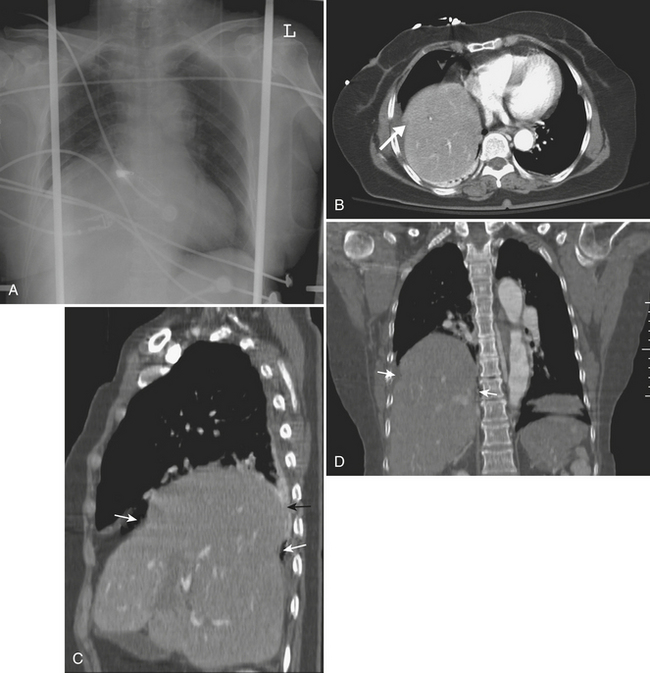

AORTIC AND GREAT VESSEL INJURIES

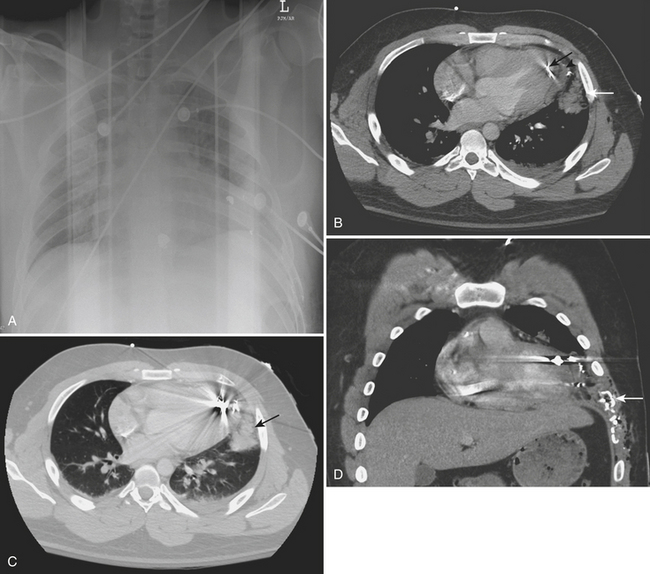

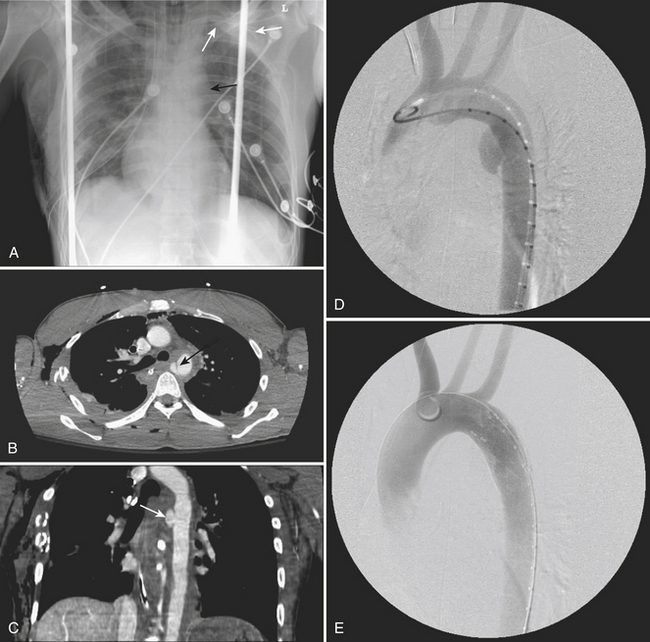

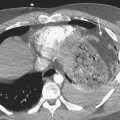

The CT findings of aortic trauma include indirect signs, such as mediastinal hematoma surrounding the posterior aortic arch and proximal descending aorta, as well as the direct signs of intimal tear/flap, aortic contour abnormality, thrombus protruding into the aortic lumen, false aneurysm formation, pseudocoarctation, and extravasation of intravenous contrast material. If only direct signs are utilized, the sensitive and negative predictive value remains at 100% but the specificity increases to 96% (Fig. 2-4).

A common aortic injury is a traumatic false aneurysm resulting from disruption of the vessel intima and media while the adventitia remains intact. The intravascular blood confined by only the adventitia bulges outward forming a pseudoaneurysm. In many cases, the aortic injury may be limited to a partial circumferential tear. CT findings typically consist of a saccular out-pouching demarcated from the aortic lumen by torn intima. It frequently results in hemomediastinum. Treatment of a pseudoaneurysm may today be performed with intravascular stent grafting. False positive examinations may be related to a prominent ductus diverticulum or an ulcerated atheromatous plaque. A traumatic pseudoaneurysm is usually surrounded by mediastinal blood whereas a ductus diverticulum and an ulcerated atheromatous plaque are not (Figs. 2-5 to 2-7).

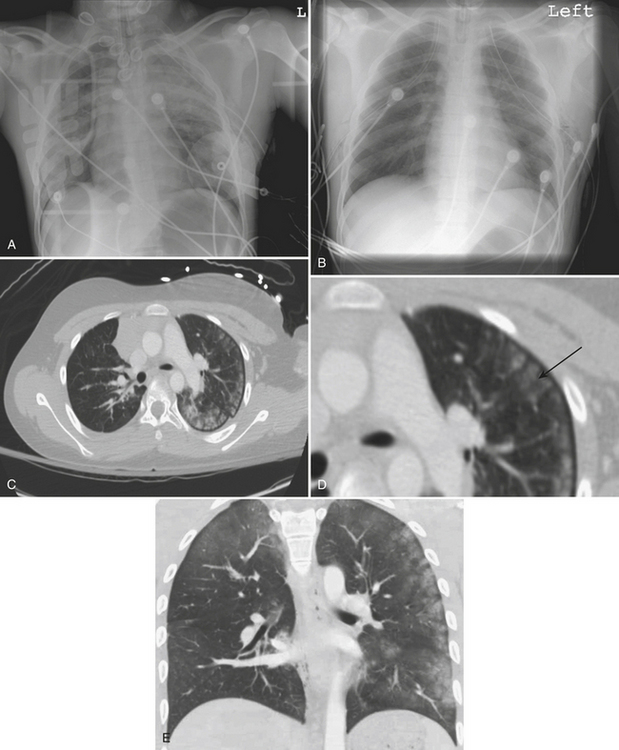

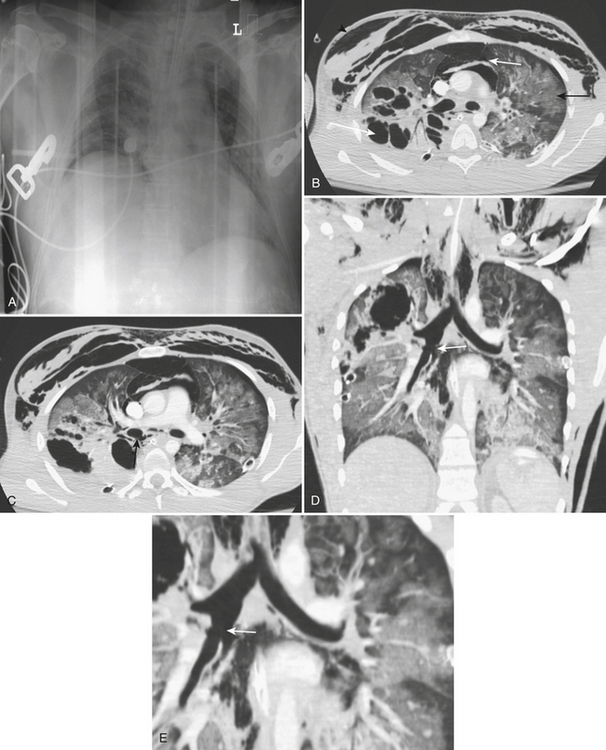

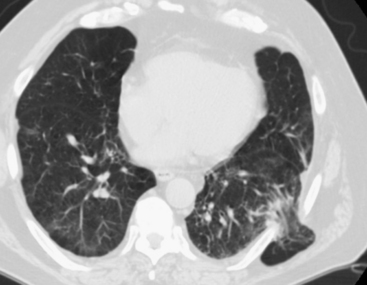

LUNG INJURIES AND LUNG CONTUSION

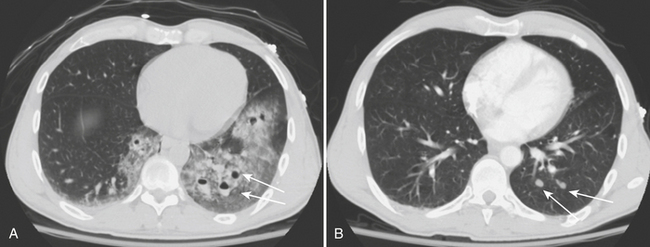

Lung contusion results from traumatic extravasation of blood and edema fluid into the pulmonary interstitium and air spaces of the lung as a result of disruption of alveolar-capillary integrity without significant disruption of the pulmonary parenchyma. The injury is caused by energy transmitted directly to the lung from an impact to the overlying chest wall. On radiographs, contusion appears as patchy areas of consolidation (Fig. 2-8). When extensive, radiographs may show diffuse dense homogeneous lung consolidation. These opacities resulting from lung contusion are said to differ from those of bronchopneumonia and aspiration in that they are not confined to the anatomic limits of various segments or lobes. This may be difficult to definitively ascertain on an initial anteroposterior chest radiograph. Contusion may be absent on the initial chest film but usually becomes evident within 6 hours of injury. CT can usually detect pulmonary contusion immediately after injury. Contusions usually resolve rapidly and disappear in a few days.

LUNG LACERATION

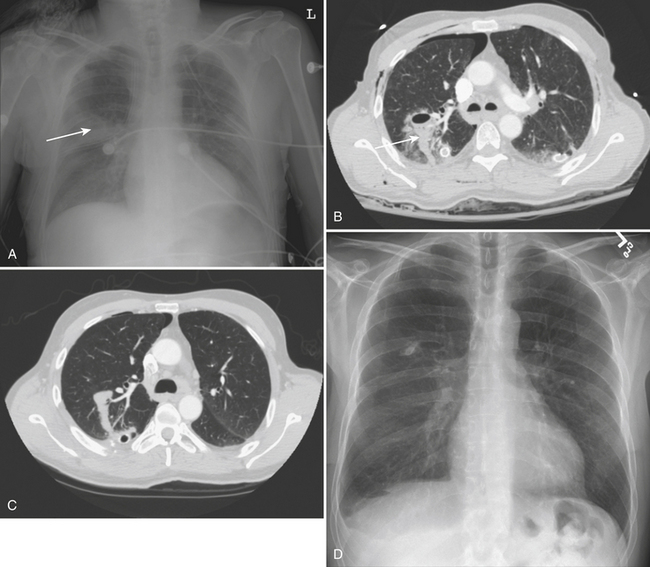

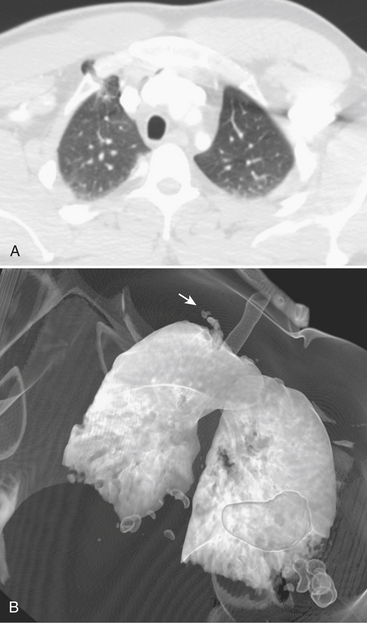

Pulmonary lacerations are tears of the lung parenchyma that fill with air, blood, or both. If the laceration fills with air the injury is termed a traumatic pneumatocele. If it fills with blood a spherical hematoma or hematocele forms. If both air and fluid are present, an air–fluid level may be identified. The spherical shape of intraparenchymal lacerations has been attributed to normal elastic recoil of the lung parenchyma pulling centrifugally in all directions on the disrupted region (Fig. 2-9).

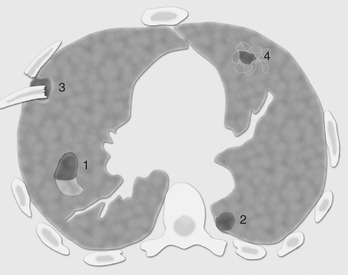

On chest radiograph, lacerations may initially be obscured by surrounding lung contusion; however, they become visible once the contusion clears. In contrast, acute lung lacerations are nearly always detected on CT imaging. Four types have been described with blunt trauma (Fig. 2-10): type 1, compression rupture laceration, resulting from sudden compression of a pliable chest wall wherein the air-containing lung is ruptured; type 2, compression shear laceration, which occurs in a para-vertebral lower lobe of the lung (the mechanism occurs when the more pliable lower chest wall is acutely compressed causing the lower lobe to shift suddenly across the vertebral body in a shearing-type injury, Fig. 2-11); type 3, rib penetration tear, causing a peripheral injury adjacent to a rib fracture (a pneumothorax is generally associated with this type of injury as it represents a penetrating injury); type 4, adhesion tear, which results from tear of prior pleural-pulmonary adhesions causing the lung to tear when the overlying chest wall is violently moved inward or fractured. Lung lacerations may also result from penetrating trauma, most frequently from stab wounds and gunshot wounds. Pulmonary lacerations are better shown and more extensively evaluated with CT than with plain films. Unlike pulmonary contusion, lung lacerations may take weeks or months to heal and may result in residual lung scarring. Frequently, as lacerations resolve they appear as lung nodules (Fig. 2-12).

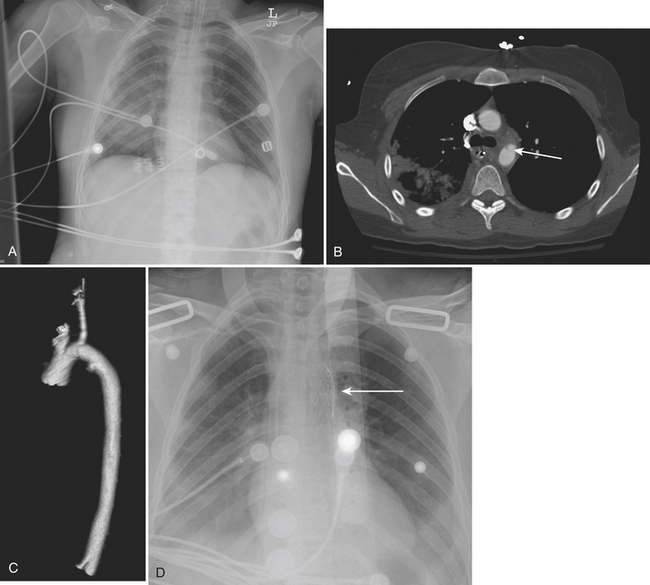

TRACHEOBRONCHiAL INJURIES

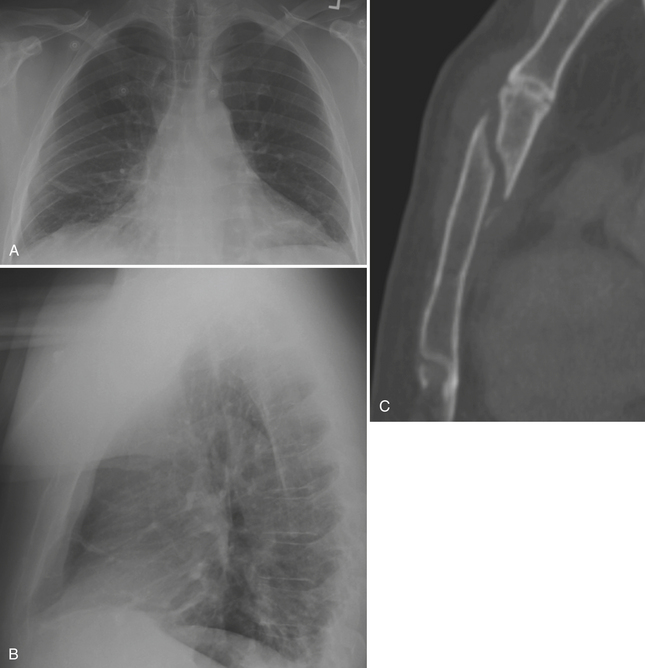

Injuries to the airways are uncommon, occurring in approximately 1.5% of blunt trauma cases. Tears and fractures of the tracheobronchial tree are frequently not recognized on initial imaging, and delayed diagnosis is common. Eighty percent of tracheobroncheal injuries occur within 2 cm of the carina. Rupture of the left and right mainstem bronchi occur with equal frequency. Chest radiograph findings most commonly include pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema (Fig. 2-13). Air continuously leaks through the rupture and flows into the surrounding mediastinal soft tissues with dissection up into the neck. Pneumomediastinum is an anticipated accompaniment of tracheobronchial injury. Large volumes of pneumomediastinum are easy to identify on plain radiographs, but volumes may not be visible on the initial portable chest radiograph. Pneumomediastinal air should initiate a search for possible tracheobronchial injury; however, there are other causes of pneumomediastinum, including complications of dyspnea, aggressive mechanical ventilation, and esophageal rupture. In the presence of a tracheobronchial laceration, air dissects into fascial planes as a consequence of the continuous air leak. Hence, on sequential radiographs, the subcutaneous emphysema is expected to persist or increase (Fig. 2-14).

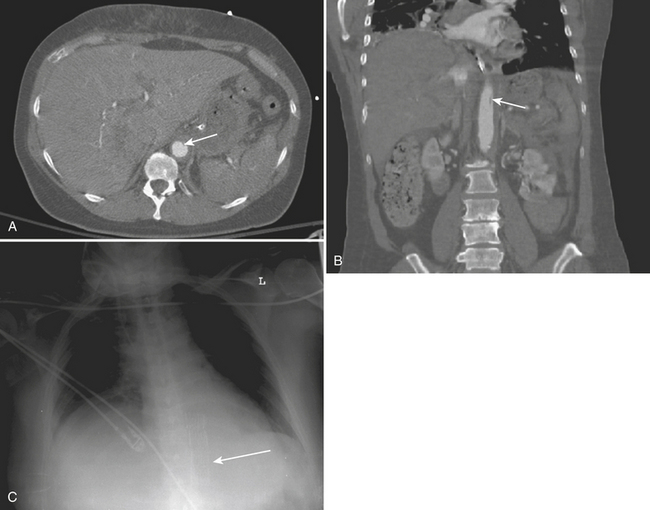

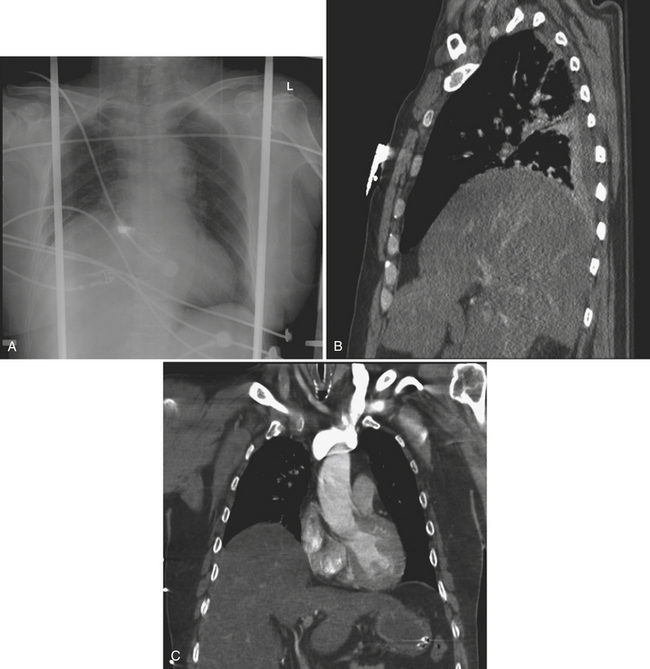

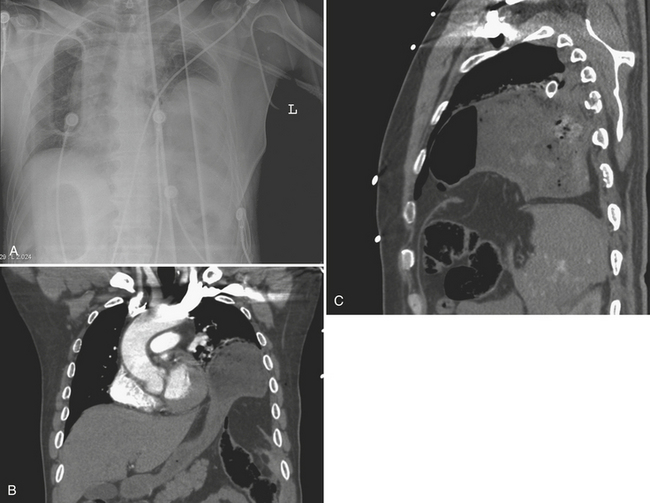

DIAPHRAGMATIC INJURIES

Left-sided injuries are more common, having a reported left-to-right ratio of 3:1. Bilateral and central tendon ruptures are uncommon. The increased frequency of left-sided injury has been attributed to an area of congenital weakness in the posterolateral diaphragm with central radiation of the tear. Right-sided injuries are thought to be less frequent because of the inherent increased strength of the right hemidiaphragm and the protective effect of the liver (Fig. 2-15).

The chest radiograph is usually the initial imaging examination of trauma patients. The supine positioning and portable technique may limit the ability to evaluate for diaphragmatic integrity. The chest radiograph may show an intrathoracic location of abdominal viscera with possible focal constriction known as the “collar” sign (Fig. 2-16). A nasogastric tube tip may be visible above the left hemidiaphragm. Significant elevation of the hemidiaphragm without associated atelectasis may be a sign of diaphragm rupture (Fig. 2-17).

Today, MDCT axial scans combined with high-quality coronal and sagittal reformations may show both large and small ruptures of the diaphragm, in addition to showing any abdominal organs herniated across the rupture. CT signs of diaphragm injury include the direct visualization of injury, intrathoracic herniation of viscera with a “collar” sign, the “dependent viscera” sign, and peridiaphragmatic active contrast extravasation. Additional findings of hemothorax, hemoperitoneum, and adjacent visceral injury may increase the suspicion of diaphragm injury. Of particular note, intrathoracic herniation of viscera is highly sensitive (up to 90.9%) when limited to left-sided injury. When abdominal viscera herniate through a diaphragm tear, the edges of the diaphragm may constrict the herniated organ, resulting in the “collar.” The “dependent viscera” sign is diagnostic of diaphragm rupture (Fig. 2-18). An intact diaphragm prevents the upper abdominal viscera from directly contacting the posterior chest wall in the supine patient. Conversely, when the diaphragm is torn, the viscera may lie dependently against the posterior chest wall.

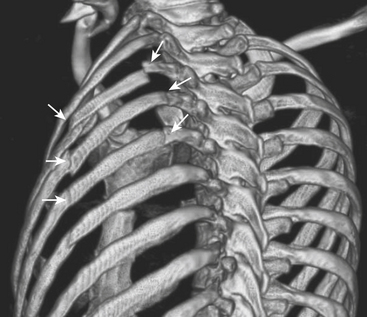

INJURIES OF THE THORACIC SKELETON

Skeletal injuries of the thorax may be apparent on initial portable chest radiograph imaging. Therefore, a careful evaluation for rib fractures should be performed. Knowledge of the presence of rib fractures may result in a CT scan for further evaluation given that the fractures may be a harbinger of more extensive underlying injury. Fractured ribs may lacerate the pleura or lung. Upper rib fractures indicate “high-energy” trauma, as these ribs are relatively well protected by the shoulder girdle and adjacent musculature. Upper rib fractures may be associated with injuries of the aorta, great vessels, or brachial plexus. Lower rib fractures may be associated with injuries to the liver, spleen, or kidneys. Flail chest occurs when five contiguous simple or three contiguous segmental rib fractures occur and result in paradoxical movement of the chest wall (Fig. 2-19). Flail chest may lead to altered chest wall mechanics and interfere with ventilation, and may lead to respiratory failure. There is a much greater incidence of rib fractures in older patients, whose ribs are fairly inelastic, as compared with children where the incidence of fracture is low secondary to more pliable and resilient ribs. Chest radiographs are limited, as they may show only 40% to 50% of rib fractures. Nearly all skeletal injuries are better shown with CT.

Rarely, a segment of lung may herniate through a defect in the chest wall created by rib or costochondral fracture (Figs. 2-20 and 2-21). The incidence of transthoracic lung herniation increases with the use of positive-pressure ventilation. Lung herniation may occur as a result of blunt chest trauma or iatrogenic surgical trauma. The herniated lung may become entrapped or strangulated. Since lung herniation may increase with positive-pressure ventilation, it may require treatment before mechanical ventilation and general anesthesia.

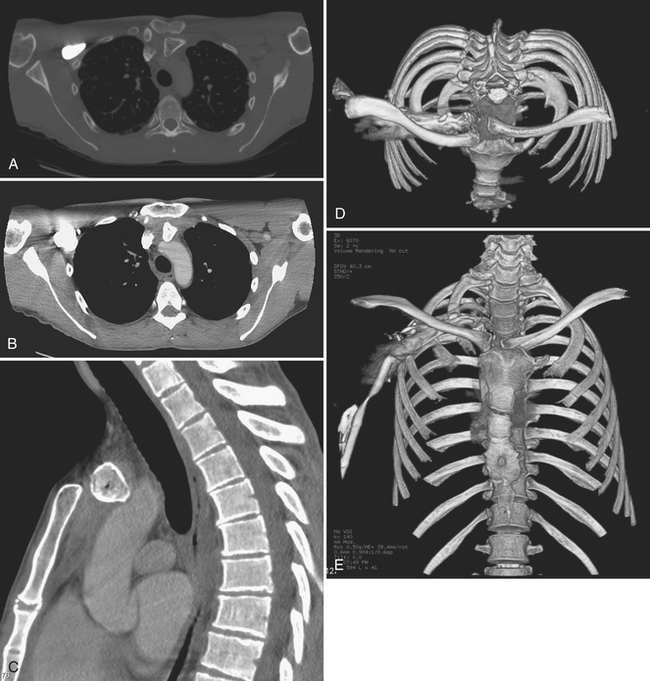

Other common injuries of the thoracic skeleton include scapular fractures, sternal fractures, sternoclavicular dislocation, and thoracic spine injuries. Posterior sternoclavicular dislocation typically results from a posterior blow to the shoulder or a blow to the medial clavicle; the latter results in a posteriorly displaced clavicular head relative to the manubrium (Fig. 2-22). Serious morbidity and even death have been associated with posterior dislocation of the clavicle at the sternoclavicular joint, as the displaced clavicle head may impinge on or injure the trachea, esophagus, great vessels, or major nerves in the superior mediastinum. Anterior sternoclavicular dislocations usually result from an anterior blow to the shoulder. Anterior dislocations are more common than posterior dislocations, and typically are less dangerous as there is no significant risk of great vessel injury. Sternoclavicular dislocation is generally well shown by CT.

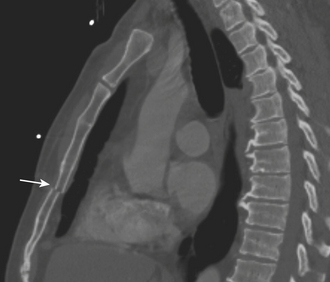

Sternal fractures are usually not seen on the anteroposterior portable chest radiograph and may be difficult to see on the lateral chest radiograph. However, nearly all sternal fractures are visible on CT, especially on sagittal reformations (Fig. 2-23). As well, CT frequently shows any associated retrosternal hematoma. Sternal fractures have a high association with both aortic and cardiac injuries. Most patients with sternal fractures are monitored for myocardial contusion with serial enzyme analysis and telemetry monitoring (Fig. 2-24).

Collins J., Primack S.L. CT of non-penetrating chest trauma. Applied Radiology Online. 2001;30:1-10.

Groskin S.A. Selected topics in chest trauma. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1996;17:119-141.

Mazurek A. Pediatric injury patterns. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1994;32:11-25.

Sevitt S. The mechanisms of traumatic rupture of the thoracic aorta. Br J Surg. 1977;64:166-173.

Wiot J.F. The radiologic manifestations of blunt chest trauma. JAMA. 1975;231:500-503.