Chest Radiography in Pediatric Cardiovascular Disease

A systematic approach to evaluation of the chest film consists of an assessment of heart size, shape, and position; pulmonary vasculature; the airway and mediastinum; visceral situs; and skeletal abnormalities. Applying such an approach often results in a diagnosis of a cardiovascular disease category such as a shunt or a right- or left-sided obstructive lesion, which in turn leads to a differential diagnosis and the identification of the likely etiology of nonspecific clinical findings, such as congestive heart failure or cyanosis (Box 65-1).

Technique

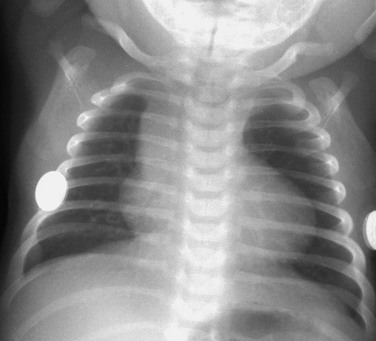

As in all medical imaging, attention to detail is necessary to optimize the examination and its interpretation. Proper exposure, centering, collimation, patient positioning, and inspiration are necessary (e-Fig. 65-1).

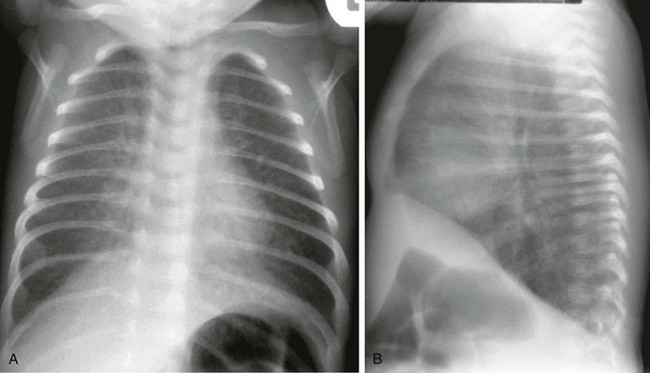

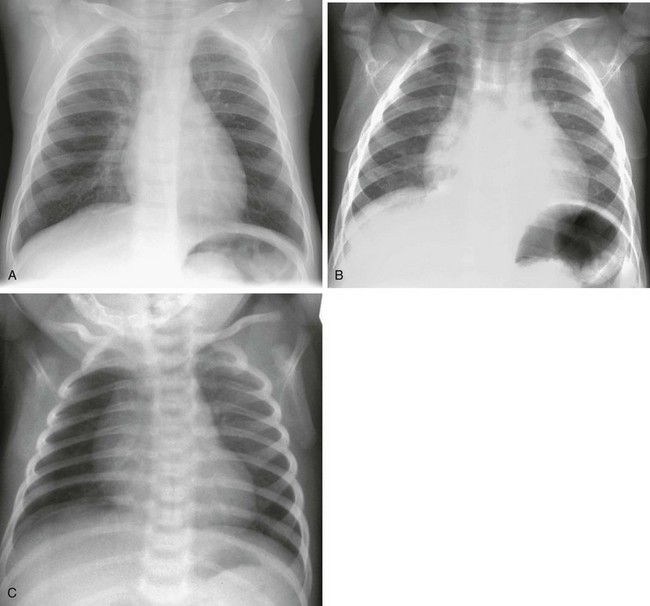

e-Figure 65-1 A normal chest examination in an infant.

Frontal radiographs in inspiration (A) and expiration (B) show the profound impact of an expiratory film on the appearance of the heart and lungs. In another example (C), a lucent right lung reflects patient rotation to the right rather than asymmetrical pulmonary blood flow.

Systematic Interpretation

One of the challenges in evaluating the chest radiograph of younger children is their variable anatomy and physiology. For example, the thymus is variable in size and position and may mimic cardiomegaly, abnormally positioned vessels, pericardial fluid, or a mediastinal mass (e-Fig. 65-2).

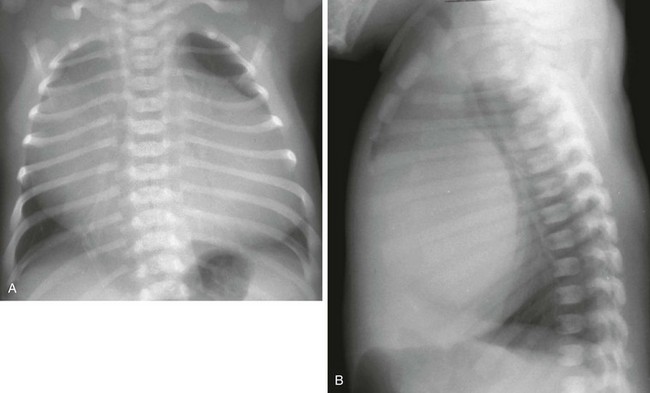

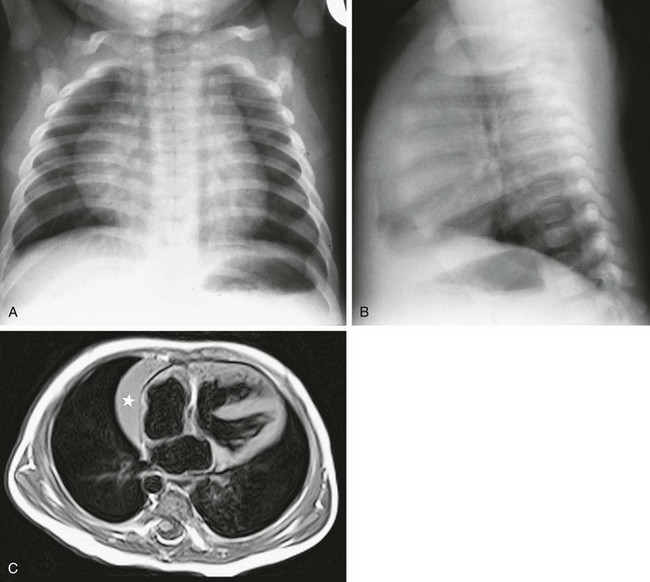

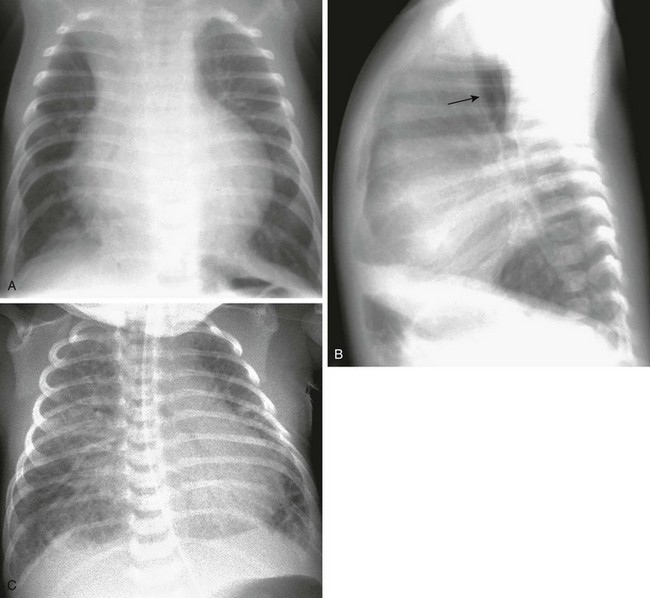

e-Figure 65-2 A normal chest examination in an infant.

A frontal chest radiograph (A) shows a large cardiomediastinal silhouette, which on lateral view (B) reflects a normal heart and a large retrosternal thymus. In another child, a T1-weighted axial magnetic resonance image of the chest (C) shows the right lobe of the thymus (star) beside the right atrium. Note also the ventricular septal defect.

Newborn infants have physiologic pulmonary hypertension, and as a result, large shunt lesions do not appear until the pulmonary vascular resistance falls, which usually occurs by 4 to 6 weeks (Fig. 65-3). Similarly, newborn infants may not show the expected changes of severe pulmonary stenosis or atresia if the ductus arteriosus is patent.

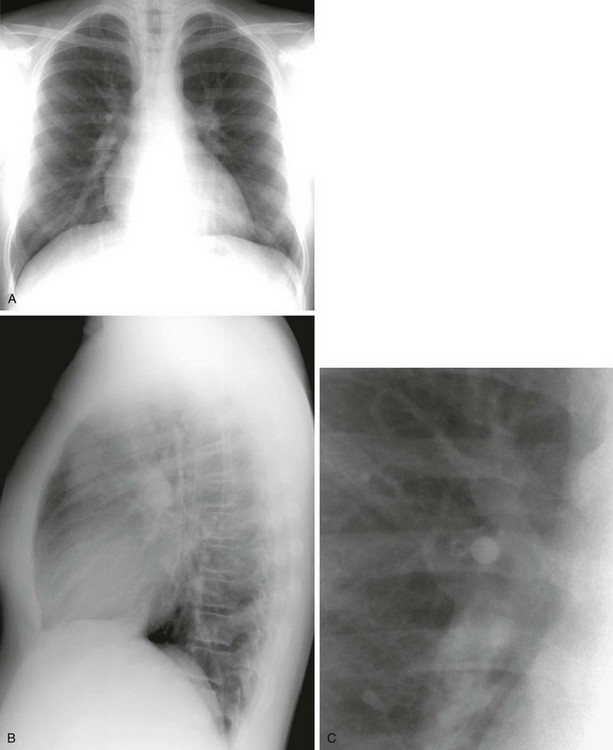

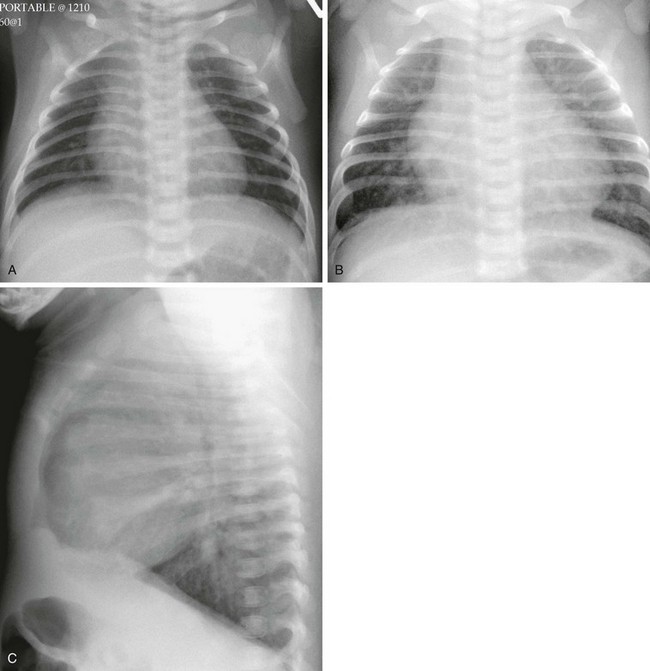

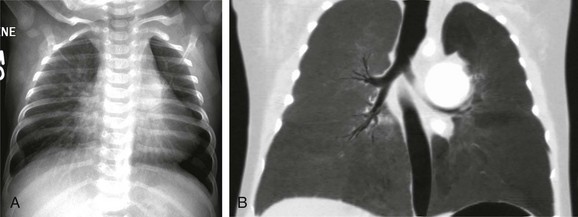

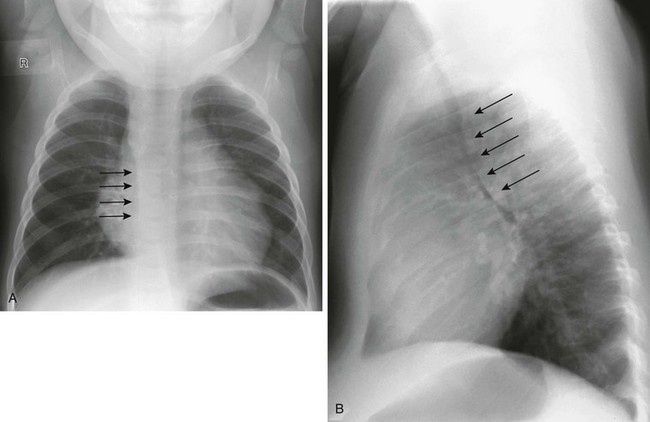

Figure 65-3 Complete transposition of the great arteries in a neonate.

A frontal radiograph (A) on day 1 of life shows a heart that is within normal limits in size and shows normal pulmonary vascularity. The same child at 7 weeks of age (B and C) has an enlarged heart and increased pulmonary vascularity. Volume loading of the heart and pulmonary circulation has occurred as pulmonary vascular resistance has dropped.

The physiology of small airways in infants and young children (up to approximately 2 years of age) results in unique manifestations of pulmonary edema. Specifically, infants show hyperinflation as a response to interstitial edema, as would happen in the presence of airway inflammation with bronchiolitis (Figs. 65-3 and 65-4).

Heart Size

The size of the heart can be difficult to assess in the frontal projection of infants and young children because of the presence of the relatively large thymus and poor inspiration (see e-Figs. 65-1 and 65-2). Measurement of the cardiothoracic ratio is of little use. The lateral view provides a more reliable indication of true heart size by permitting an assessment of the anteroposterior dimension without interference from the thymus. However, the thymus does fill in the retrosternal space, obscuring the right ventricular outflow tract. In older children, the frontal radiograph is more useful, and the radiologist should evaluate both views to assess the three-dimensional volume of the heart. In a child with pectus excavatum, the heart may appear large in the frontal view but compressed in the lateral film. Marked cardiomegaly is seen in children with severe valve regurgitation, especially tricuspid valve disease (Ebstein anomaly), pericardial effusion, and cardiomyopathy, and it is rarely seen in children with cardiac tumors. Mediastinal masses may mimic cardiomegaly (e-Fig. 65-5).

Pulmonary Vasculature

Chest radiography provides a window into the pulmonary circulation, which is the main area in which chest radiography supplements the information gained from echocardiography. The pulmonary vasculature may show evidence of increased flow, decreased flow, normal flow, or pulmonary venous hypertension. The pulmonary flow may be asymmetrical in the setting of tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia, or other rare lesions. The assessment of the pulmonary vasculature is both important and difficult. Poor-quality films that are rotated or obtained during expiration are difficult to interpret (see e-Fig. 65-1). Many radiographs in younger children are obtained in the supine position, and therefore flow is symmetrical from base to apex.

Increased Pulmonary Vascularity

The size of the pulmonary vessels is noticeably larger only when the amount of flow doubles (thus when the pulmonary/systemic ratio is 2 : 1) (e-Figs. 65-6 and 65-7).

e-Figure 65-6 Ventricular septal defect in an infant.

Frontal (A) and lateral (B) chest radiographs show cardiomegaly with increased pulmonary vascularity. The pulmonary vessels are prominent in the hilar regions and taper in a normal fashion, extending into the periphery of the lung. On the lateral radiograph (B), the left bronchus is displaced posteriorly by the enlarged left atrium (arrow). The lungs are hyperinflated and mild interstitial thickening is present, representing congestive heart failure.

Decreased Pulmonary Vascularity

Identifying decreased vascularity is even more difficult than identifying increased flow (e-Fig. 65-8).

e-Figure 65-8 Tetralogy of Fallot in an infant.

A frontal radiograph of the chest shows a mildly enlarged heart and decreased pulmonary vascularity.

A cyanotic child beyond the newborn period whose flow appears to be within normal limits very likely has a right-to-left shunt Box 65-2.

Pulmonary Venous Hypertension and Pulmonary Edema

Early pulmonary venous hypertension often manifests as hyperinflation in infants younger than 2 years (see Fig. 65-4 and e-Fig. 65-6). As interstitial fluid accumulates, the perihilar bronchi and vessels become poorly defined. Septal (i.e., Kerley) lines are uncommon in children. Eventually, frank alveolar pulmonary edema is seen. In the presence of severe heart failure, it can be difficult to determine whether the failure is caused by pulmonary venous hypertension alone or is associated with an underlying large left-to-right shunt (e-Fig. 65-9) (Box 65-3). Pulmonary edema can obscure vessel detail, and left heart failure can distend the vessels. The detection of heart disease can be difficult in the child who presents with an acute viral respiratory illness because the inflammation can produce ill-defined vascular markings and hyperinflation similar to the findings in congestive heart failure. In a supine patient, pleural fluid will layer posteriorly. Unlike in children with large shunts, with left-sided obstruction or pump failure, the heart often is disproportionate to the vascularity (e-Fig. 65-9, A)

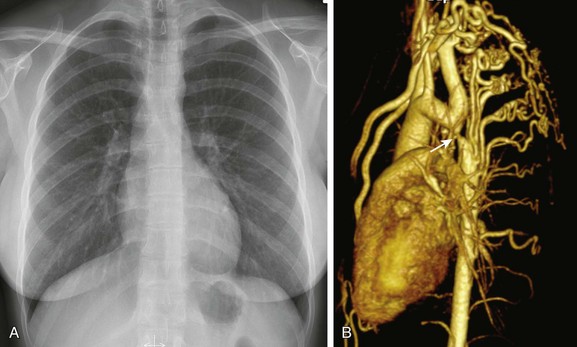

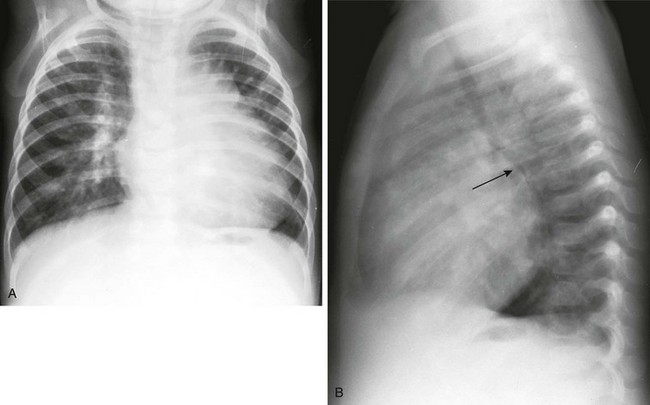

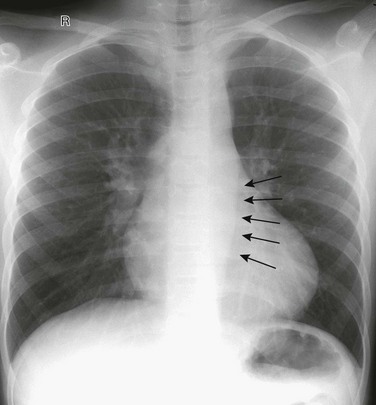

e-Figure 65-9 Coarctation of the aorta.

Frontal (A) and lateral (B) chest radiographs in a 2-month-old show cardiomegaly, normal pulmonary blood flow, and evidence of congestive heart failure as shown by mild interstitial thickening and obvious hyperinflation. Note the posterior displacement of the trachea (arrow) by the enlarged heart on the lateral projection. In another child (C) who presented in the first week of life with severe congestive heart failure due to coarctation of the aorta, it is difficult to determine from the chest radiograph whether there is increased vascularity caused by a shunt or simply severe pulmonary venous hypertension. This child had no associated left-to-right shunt.

Centralized Pulmonary Vascularity

Prominence of the perihilar vessels with rapid tapering as a sign of pulmonary arterial hypertension is rarely seen in children. In a rare variation of tetralogy of Fallot with absent pulmonary valve (not to be confused with pulmonary atresia), large hilar vessels may be seen even during the newborn period, but they are not caused by pulmonary arterial hypertension (e-Fig. 65-10).

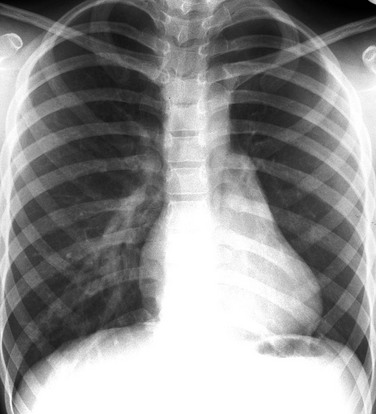

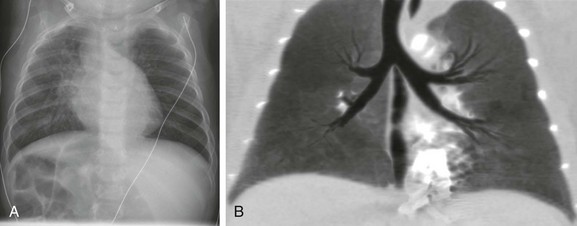

e-Figure 65-10 Tetralogy of Fallot with an absent pulmonary valve.

A frontal chest radiograph (A) shows a greatly enlarged proximal left pulmonary artery in a 2-month-old infant. A coronal minimum intensity projection computed tomography image (B) shows the marked dilatation of the central left pulmonary artery and bronchial compression.

Asymmetrical Pulmonary Flow

The chest film must be carefully evaluated for asymmetrical flow, which can occur as a result of pulmonary arterial stenosis or hypoplasia, pulmonary venous obstruction, or disturbances in ventilation with secondary vasoconstriction, as well as postoperatively. Care must be taken to avoid misinterpretation of the rotated radiograph (see e-Fig. 65-1). In children with decreased pulmonary blood flow as a result of tetralogy of Fallot or pulmonary atresia, stenosis of the pulmonary artery (usually the left at the site of ductal insertion) is a common problem (e-Fig. 65-11).

e-Figure 65-11 Tetralogy of Fallot with left pulmonary artery stenosis in a 7-year-old girl.

A frontal chest radiograph shows decreased vascularity in the left lung as a result of pulmonary artery stenosis and hypoplasia. As a consequence of chronic underperfusion, the left lung and hemithorax are underdeveloped.

Airway and Mediastinum

The chest film is evaluated for the presence of the thymus, a mediastinal mass, the side of the aortic arch, and the presence of a vascular ring. The size and position of the trachea is an important indicator of arch abnormalities. A careful search should be made on both frontal and lateral films for displacement or narrowing of the trachea (e-Fig. 65-12).

e-Figure 65-12 A double aortic arch.

A frontal radiograph of the chest (A) shows a right-sided aortic arch and a right-sided descending aorta (arrows). The trachea is in the midline and the air column appears narrow on the frontal projection. The lateral view (B) shows anterior displacement and narrowing (arrows) of the air column as a result of the vascular ring.

Mechanical displacement or obstruction of large airways occurs in anomalies of the aortic arch, pulmonary arteries, and more severe forms of cardiomegaly (see e-Figs. 65-5, 65-6, 65-7, 65-9, 65-10, and 65-12). The position and contour of the descending aorta should be carefully examined. In coarctation of the aorta, the only sign in younger children may be a leftward convexity to the descending aorta (e-Fig. 65-13). Such a contour is seen often in older adults as a result of age-related ectasia, but it is abnormal in children.

e-Figure 65-13 Coarctation of the aorta in a 10-year-old girl.

A frontal radiograph of the chest shows an outward convexity to the descending thoracic aorta (arrows) caused by poststenotic dilation. The poststenotic dilation is more prominent than the arch above the coarctation. Compare this convexity with e-Figure 65-1, A, where the normal contour is seen easily.

Situs

The chest film assessment is incomplete unless abnormalities of abdominal and thoracic situs (the anatomic location of organs that are asymmetrically positioned in the body) are sought and the cardiac position relative to visceral situs is determined. Dextrocardia in situs solitus is strongly associated with complex cardiac abnormalities. Abnormal situs can be subtle, with a normal-appearing liver and stomach. Airway anatomy and lung morphology are valuable indicators of visceral situs. Symmetrical bronchi are seen in almost all patients with right isomerism (asplenia) (e-Fig. 65-14) and in 68% of patients with left isomerism (polysplenia). Splenic dysfunction and intestinal malrotation occur in these children.

e-Figure 65-14 A 7-month-old child with complex congenital heart disease and asymmetrical pulmonary blood flow.

Discordance between the cardiac position and the abdominal viscera is shown on a frontal chest radiograph (A). The bronchi appear symmetrical. A coronal minimum intensity projection image from a computed tomography scan (B) confirms right isomerism.

Bony Abnormalities

A complete evaluation of the chest radiograph must include the bony thorax. Few skeletal abnormalities are strongly associated with congenital heart disease, but abnormalities of the spine (e.g., scoliosis, segmentation anomalies, and rib anomalies) and sternum (e.g., an abnormal number of ossification centers and caudal deficiency) occur. Rib notching is rarely seen in younger children with aortic coarctation, but it may be present in adolescents and teenagers in whom intercostal artery collaterals have developed (e-Fig. 65-15). Bony changes are common after a thoracotomy.

Donnelly, LF, Gelfand, KJ, Schwartz, DC, et al. The “wall to wall” heart: Massive cardiothymic silhouette in newborns. Appl Radiol. 1997;26:23–28.

Kellenberger, CJ. Aortic arch malformations. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:876–884.

Laya, BF, Goske, MJ, Morrison, S, et al. The accuracy of chest radiographs in the detection of congenital heart disease and in the diagnosis of specific congenital cardiac lesions. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:677–681.

Markowitz, RI, Fellows, KE. The effects of congenital heart disease on the lungs. Semin Roentgenol. 1998;33:126–135.

Strife, JL, Sze, RW. Radiographic evaluation of the neonate with congenital heart disease. Radiol Clin North Am. 1999;37:1093–1107.