Chapter 4

Chest Radiographs

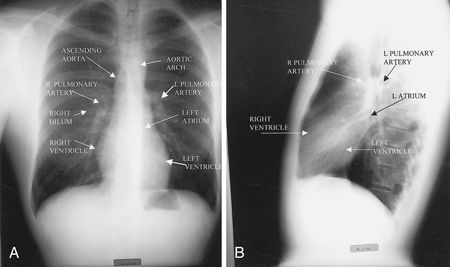

1. Describe a systematic approach to interpreting a chest radiograph (chest x-ray [CXR]) (Fig. 4-1).

Figure 4-1 Diagrammatic representations of the anatomy of the chest radiograph. A, Aor, Aorta; IVC, inferior vena cava; LAA, left atrial appendage; LPA, left pulmonary artery; LV, left ventricle; PT, pulmonary trunk; RA, right atrium; RPA, right pulmonary artery; RV, right ventricle; SVC, superior vena cava; Tr, trachea. B, IVC, inferior vena cava; LPA, left pulmonary artery; LV, left ventricle; RPA, right pulmonary artery; RV, right ventricle; Tr, trachea. (From Inaba AS: Cardiac disorders. In Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R, editors: Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2006, Mosby.)

Common recommendations are to:

1. Begin with general characteristics such as the age, gender, size, and position of the patient.

2. Next, examine the periphery of the film, including the bones, soft tissue, and pleura. Look for rib fractures, rib notching, bony metastases, shoulder dislocation, soft tissue masses, and pleural thickening.

3. Then, evaluate the lung, looking for infiltrates, pulmonary nodules, and pleural effusions.

4. Finally, concentrate on the heart size and contour, mediastinal structures, hilum, and great vessels. Also note the presence of pacemakers and sternal wires.

2. Identify the major cardiovascular structures that form the silhouette of the mediastinum (Fig. 4-2)

Right side: Ascending aorta, right pulmonary artery, right atrium, right ventricle

Right side: Ascending aorta, right pulmonary artery, right atrium, right ventricle

Left side: Aortic knob, left pulmonary artery, left atrial appendage, left ventricle

Left side: Aortic knob, left pulmonary artery, left atrial appendage, left ventricle

3. How is heart size measured on a chest radiograph?

4. What factors can affect heart size on the chest radiograph?

Size of the patient: Obesity decreases lung volumes and enlarges the appearance of the heart.

Size of the patient: Obesity decreases lung volumes and enlarges the appearance of the heart.

Degree of inspiration: Poor inspiration can make the heart appear larger.

Degree of inspiration: Poor inspiration can make the heart appear larger.

Emphysema: Hyperinflation changes the configuration of the heart, making it appear smaller.

Emphysema: Hyperinflation changes the configuration of the heart, making it appear smaller.

Contractility: Systole or diastole can make up to a 1.5-cm difference in heart size. In addition, low heart rate and increased cardiac output lead to increased ventricular filling.

Contractility: Systole or diastole can make up to a 1.5-cm difference in heart size. In addition, low heart rate and increased cardiac output lead to increased ventricular filling.

Chest configuration: Pectus excavatum can compress the heart and make it appear larger.

Chest configuration: Pectus excavatum can compress the heart and make it appear larger.

Patient positioning: The heart appears larger if the film is taken in a supine position.

Patient positioning: The heart appears larger if the film is taken in a supine position.

Type of examination: On an AP projection, the heart is farther away from the film and closer to the camera. This creates greater beam divergence and the appearance of an increased heart size.

Type of examination: On an AP projection, the heart is farther away from the film and closer to the camera. This creates greater beam divergence and the appearance of an increased heart size.

5. What additional items should be reviewed when examining a chest radiograph from the intensive care unit (ICU)?

On portable coronary care unit (CCU) and ICU radiographs, particular attention should be paid to:

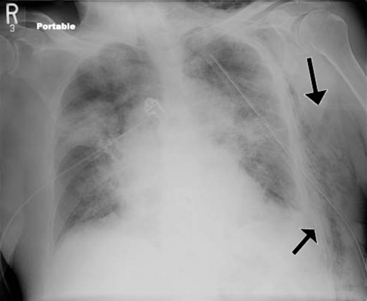

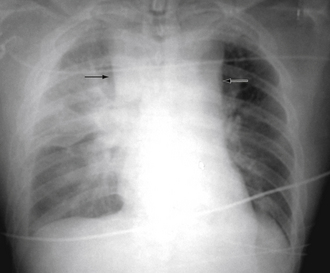

A careful inspection should be made for pneumothorax (Fig. 4-3), subcutaneous emphysema, and other factors that may be related to instrumentation and mechanical ventilation.

Figure 4-3 Tension pneumothorax. On a posteroanterior chest radiograph (A) the left hemithorax is very dark or lucent because the left lung has collapsed completely (white arrows). The tension pneumothorax can be identified because the mediastinal contents, including the heart, are shifted toward the right (black arrows) and the left hemidiaphragm is flattened and depressed. B, A computed tomography scan done on a different patient with a tension pneumothorax shows a completely collapsed right lung (arrows) and shift of the mediastinal contents to the left. (From Mettler: Essentials of radiology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders.)

6. How can one determine which cardiac chambers are enlarged?

Ventricular enlargement: usually displaces the lower heart border to the left and posteriorly. Distinguishing right ventricular (RV) from left ventricular (LV) enlargement requires evaluation of the outflow tracts. In RV enlargement, the pulmonary arteries are often prominent and the aorta is diminutive. In LV enlargement, the aorta is prominent and the pulmonary arteries are normal.

Ventricular enlargement: usually displaces the lower heart border to the left and posteriorly. Distinguishing right ventricular (RV) from left ventricular (LV) enlargement requires evaluation of the outflow tracts. In RV enlargement, the pulmonary arteries are often prominent and the aorta is diminutive. In LV enlargement, the aorta is prominent and the pulmonary arteries are normal.

Left atrial (LA) enlargement: creates a convexity between the left pulmonary artery and the left ventricle on the frontal view. Also, a double density may be seen inferior to the carina. On the lateral view, LA enlargement displaces the descending left lower lobe bronchus posteriorly.

Left atrial (LA) enlargement: creates a convexity between the left pulmonary artery and the left ventricle on the frontal view. Also, a double density may be seen inferior to the carina. On the lateral view, LA enlargement displaces the descending left lower lobe bronchus posteriorly.

Right atrial enlargement: causes the lower right heart border to bulge outward to the right.

Right atrial enlargement: causes the lower right heart border to bulge outward to the right.

7. What are some of the common causes of chest pain that can be identified on a chest radiograph?

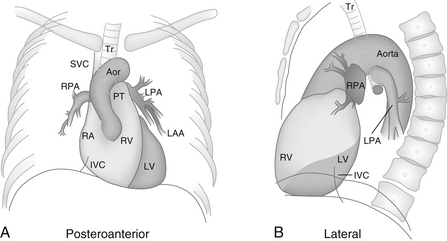

8. What are the causes of a widened mediastinum?

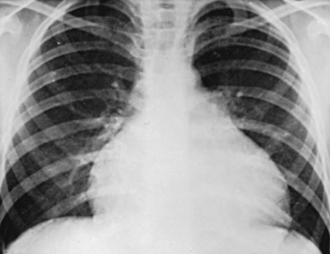

There are multiple potential causes of a widened mediastinum (Fig. 4-4). Some of the most concerning causes of mediastinal widening include aortic dissection and/or rupture and mediastinal bleeding from chest trauma or misplaced central venous catheters. One of the most common causes of mediastinal widening is thoracic lipomatosis in an obese patient. Tumors should also be considered as a cause of a widened mediastinum—especially germ cell tumors, lymphoma, and thymomas. The mediastinum may also appear wider on a portable AP film compared with a standard posteroanterior/lateral chest radiograph.

Figure 4-4 Widened mediastinum (arrows). (From Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R, editors: Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2006, Mosby.)

9. What are the common radiographic signs of congestive heart failure?

10. What is vascular redistribution? When does it occur in congestive heart failure?

11. How does LV dysfunction and RV dysfunction lead to pleural effusions?

LV dysfunction causes increased hydrostatic pressures, which lead to interstitial edema and pleural effusions. Right pleural effusions are more common than left pleural effusions, but the majority are bilateral.

LV dysfunction causes increased hydrostatic pressures, which lead to interstitial edema and pleural effusions. Right pleural effusions are more common than left pleural effusions, but the majority are bilateral.

RV dysfunction leads to system venous hypertension, which inhibits normal reabsorption of pleural fluid into the parietal pleural lymphatics.

RV dysfunction leads to system venous hypertension, which inhibits normal reabsorption of pleural fluid into the parietal pleural lymphatics.

12. How helpful is the chest radiograph at identifying and characterizing a pericardial effusion?

The CXR is not sensitive for the detection of a pericardial effusion, and it may not be helpful in determining the extent of an effusion. Smaller pericardial effusions are difficult to detect on a CXR but can still cause tamponade physiology if fluid accumulation is rapid. A large “water bottle” cardiac silhouette (Fig. 4-5), however, may suggest a large pericardial effusion. Distinguishing pericardial fluid from chamber enlargement is often difficult.

Figure 4-5 The water bottle configuration that can be seen with a large pericardial effusion. (From Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al: Nelson textbook of pediatrics, ed 18, Philadelphia, 2007, Saunders.)

13. What are the characteristic radiographic findings of significant pulmonary hypertension?

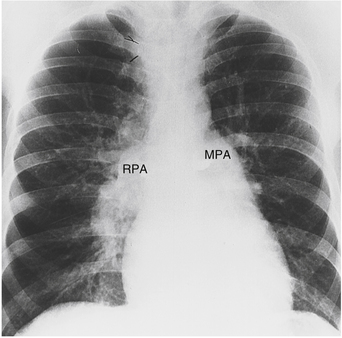

Enlargement of the central pulmonary arteries with rapid tapering of the vessels is a characteristic finding in patients with pulmonary hypertension (Fig. 4-6). If the right descending pulmonary artery is greater than 17 mm in transverse diameter, it is considered enlarged. Other findings of pulmonary hypertension include cardiac enlargement (particularly the right ventricle) and calcification of the pulmonary arteries. Pulmonary arterial calcification follows atheroma formation in the artery and represents a rare but specific radiographic finding of severe pulmonary hypertension.

Figure 4-6 Pulmonary arterial hypertension. Marked dilation of the main pulmonary artery (MPA) and right pulmonary artery (RPA) is noted. Rapid tapering of the arteries as they proceed peripherally is suggestive of pulmonary hypertension and is sometimes referred to as pruning. (From Mettler FA: Essentials of radiology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders.)

14. What is the Westermark sign and a Hampton hump?

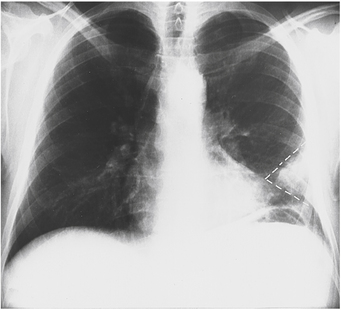

The Westermark sign is seen in patients with pulmonary embolism and represents an area of oligemia beyond the occluded pulmonary vessel. If pulmonary infarction results, a wedge-shaped infiltrate (a “Hampton hump”) may be visible (Fig. 4-7).

Figure 4-7 A peripheral wedge-shaped infiltrate (white dashed lines) seen after a pulmonary embolism has led to infarction. This finding is sometimes called a “Hampton hump.” (From Mettler FA: Essentials of radiology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2005, Saunders.)

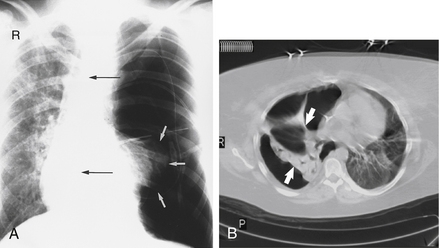

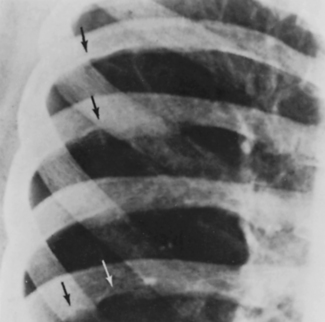

Rib notching is erosion of the inferior aspects of the ribs (Fig. 4-8). It can be seen in some patients with coarctation of the aorta and results from a compensatory enlargement of the intercostal arteries as a means of increasing distal circulation. It is most commonly seen between the fourth and eighth ribs. It is important to recognize this life-saving finding because aortic coarctation is treatable with percutaneous or open surgical intervention.

Figure 4-8 Rib notching in a patient with coarctation of the aorta. (From Park MK: Pediatric cardiology for practitioners, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2008, Mosby.)

16. What does the finding in Figure 4-9 suggest?

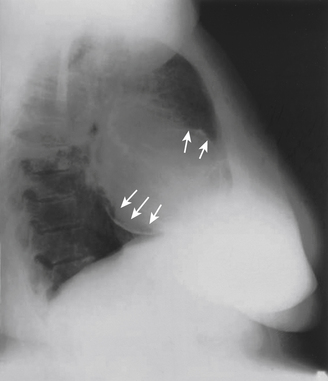

Figure 4-9 Pericardial calcification (arrows). In a patient with signs and symptoms of heart failure, this finding would strongly suggest the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis. (From Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, et al: Braunwald’s heart disease, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.)

The important finding in this figure is pericardial calcification. This can occur in diseases that affect the pericardium, such as tuberculosis. In a patient with signs and symptoms of heart failure, this finding would be highly suggestive of the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis.

17. What is subcutaneous emphysema?

Subcutaneous emphysema is the accumulation of air in the subcutaneous tissue, often tracking along tissue plains. Subcutaneous emphysema in the chest can be caused by numerous conditions, including pneumothorax, ruptured bronchus, ruptured esophagus, blunt trauma, stabbing or gunshot wound, or invasive procedure (e.g., endoscopy, bronchoscopy, central line placement, or intubation). The finding of subcutaneous emphysema almost always is associated with a serious medical condition or complication. The example of subcutaneous emphysema in Figure 4-10 emphasizes the importance of examining the entire chest x-ray.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Baron, M.G. Plain film diagnosis of common cardiac anomalies in the adult. Radiol Clin North Am. 1999;37:401–420.

2. Chandraskhar, A.J. Chest X-ray atlas. Available at http://www.meddean.luc.edu/lumen/MedEd/medicine/pulmonar/cxr/atlas/cxratlas_f.htm. Accessed March 8, 2012

3. Hollander, J.E., Chase, M. Evaluation of chest pain in the emergency department. Available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-chest-pain-in-the-emergency-department.. Accessed January 14, 2013

4. MacDonald, S.L.S., Padley, S. The mediastinum, including the pericardium. In Adam A., Dixon A.K., eds.: Grainger & Allsion’s diagnostic radiology, ed 5, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2008.

5. Meholic, A. Fundamentals of chest radiology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996.

6. Mettler, F.A. Cardiovascular system. In Mettler F.A., ed.: Essentials of radiology, ed 2, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2005.

7. Newell, J. Diseases of the thoracic aorta: a symposium. J Thorac Imag. 1990;5:1–48.