Chapter 4 Chest and chest wall problems

4.1 Introduction

Assessment of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems is usually done sequentially. The best general measure of cardiorespiratory function and of anaesthetic risk is the patient’s exercise tolerance.

To assess respiratory reserve (Box 4.1), it is important to determine how well the patient can move air, assessed at the bedside or by spirometry with forced vital capacity testing. A forced expiration time (FET) of less than three seconds is normal. A time of more than five seconds is abnormal and indicates significant obstructive airways disease, as does inability to blow out a match held at 15 cm from the mouth. Obstructive airways disease is by far the most common type of lung disease seen. It occurs as part of the degenerative effects of ageing and is exacerbated by smoking.

History

Cardiac pain is retrosternal, described as constricting or crushing, and may radiate to the neck or shoulders and arm. The pain may be brought on by exertion (angina of effort) or be continuous, suggesting myocardial infarction. Patients with angina can be classified using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, as shown in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 New York Heart Association classification of angina

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Angina with strenuous exercise |

| II | Angina with moderate exercise |

| III | Angina after climbing one flight of stairs or walking one or two blocks |

| IV | Angina with any activity |

A careful enquiry should always be made about past and present medications taken by the patient and any allergy to such medications. This should include drugs prescribed, bought over the counter and ‘alternative’ medicines. Of particular importance are cardiac drugs and those with effects that might influence the safety of surgery, including insulin and oral hypoglycaemic drugs, oral contraceptives, diuretics, digitalis, beta-blocking agents and other antihypertensives, uricosuric drugs, anti-anxiety (phenothiazine) drugs, antidepressants, sedatives and aperients. The past history may reveal relevant illnesses such as asthma, tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, rheumatic fever or occupations of significance and allergies. Smoking habits and alcohol intake must be noted. Actions to diminish intake during preoperative preparation (which can minimise and reverse cardiorespiratory damage) must commence as soon as possible.

Physical examination

Examination of the periphery

Clubbing or thickening of tissues over the terminal phalanx with rocking of the nail is found in cyanotic congenital heart disease, chronic pulmonary suppuration, lung cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, cirrhosis of the liver and thyrotoxicosis and is occasionally found as a congenital trait. Clubbing can be graded in severity (Table 4.2).

| Grade I | Obliteration of the normal angle between nail and cuticle |

| Grade II | Soft tissue thickening with nail breaking in anteroposterior plane |

| Grade III | Thickening also in a lateral plane |

Examination of the head and neck

Examination of the eyes may reveal the pallor of anaemia. A greyish yellow nodule or plaque of the eyelids (xanthoma) suggests hyperlipidaemia. A white ring (arcus) at the junction of iris and sclera can suggest advanced atherosclerosis and hyperlipoproteinaemia but can occur in older patients without these stigmata (arcus senilis). Sometimes Horner’s syndrome is detected, with eye changes of meiosis, ptosis, enophthalmos and anhidrosis secondary to sympathetic nerve paresis from an apical lung malignancy. Brachial plexus symptoms (T1 compression) may coexist (Pancoast’s syndrome). Examination of the neck may reveal the diffuse goitre of Graves’ disease. Tracheal deviation may be due to displacement of a goitre or to mediastinal shift. Enlarged cervical lymph nodes may be the only sign of carcinoma of the lung or may be part of a systemic disorder such as sarcoidosis, in which pulmonary involvement is common.

Jugular venous pressure and pulse

Differentiation between venous and arterial pulsations in the neck can sometimes be difficult. Venous pulsations are more easily seen than felt, arterial pulsations more readily felt than seen. Venous pulsation is characterised by two distinct waves in each cycle (‘double flicker’). The venous pulse will normally rise during expiration or the valsalva manoeuvre or on pressure over the liver and will fall on sitting upright. Compressing the internal jugular vein just above the clavicle eliminates the venous pulse wave. Arterial pulsation does not change with any of these (Table 4.3).

Table 4.3 Venous and arterial pulses and pressures in the neck

| Venous | Arterial | |

|---|---|---|

| Easily palpable | No | Yes |

| Visible but not palpable | Yes | No |

| Waves per cycle | Two | One |

| Changes with respiration and valsalva | *Yes | No |

| Changes with compression of neck and abdomen | *Yes | No |

| Changes with posture | *Yes | No |

Examination of the heart

Systolic murmurs are produced by valvular diseases, mitral incompetence and aortic sclerosis/stenosis or by ventricular septal defects. Fever, anxiety and pregnancy may sometimes induce benign systolic murmurs. The louder a systolic murmur, especially one associated with a thrill and cardiomegaly, the more likely it is to be of organic origin. An early systolic murmur that replaces the first sound and is transmitted into the left axilla is organic and is due to mitral incompetence and regurgitation. The aortic systolic murmur of aortic stenosis is ejection in type, midsystolic and is transmitted into the neck. Diastolic murmurs are caused by aortic incompetence, mitral stenosis or dilatation of the aortic ring in patients with marked hypertension and intracardiac shunt. The mitral stenotic murmur is diastolic with a presystolic crescendo component (unless there is atrial fibrillation) and is preceded by an opening snap, often best heard with the patient lying on the left side. The aortic incompetent murmur is in early diastole and is best heard with the patient leaning forward and holding the breath in expiration.

Finally the abdomen and legs are examined.

Left ventricular failure (Table 4.4) is characterised predominantly by symptoms such as exertional dyspnoea, cough, fatigue orthopnoea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea. Fatigue may be the chief complaint in patients with heart failure from mitral valve disease. The signs include cardiomegaly, basal crepitations in the lungs, gallop rhythm (a cadence found with tachycardia plus triple rhythm due to a loud, easily heard, third heart sound) and evidence of pulmonary venous congestion on X-ray (Kerley B lines).

| Left | Right | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Dyspnoea | Dyspnoea |

| Cough | ||

| Orthopnoea | ||

| Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea |

||

| Signs | Cardiomegaly | Elevated venous pressure |

| Gallop rhythm | ||

| Basal crepitations | Oedema | |

| Hepatomegaly |

Examination of the chest and lungs

Breath sounds are assessed. Normal breath sounds are produced in the larynx and consist of an inspiratory sound followed immediately by a shorter, softer expiratory sound, a pattern known as vesicular breathing. Vesicular breathing may be harsher in patients with prolongation of expiration from mild airways obstruction. Breath sounds are reduced or absent over effusion or pneumothorax, which poorly conduct sound from the underlying lung. Bronchial breathing is the main sign of consolidation. It has a blowing quality with an extended expiration similar to the tracheal sound, as this large tube sound is transmitted freely to the chest wall through solid lung. The sound may be soft or loud, high- or low-pitched. High-pitched (tubular) bronchial breathing is heard over pneumonic consolidation. Bronchial breathing may also be heard over fibrosed lung, a large cavity or just above an effusion.

Collapse (atelectasis) is characterised by impaired percussion with silence. The findings are of:

Pleural effusion is characterised by stony dullness with silence. The features include:

Pneumothorax is characterised by hyperresonance with silence. The features include:

4.2 Acute chest pain

Acute chest pain is always a worrying problem. Disorders of the heart, lungs and oesophagus need to be distinguished from other and less significant causes as rapidly as possible. The severity, site and radiation of pain, its precipitation and aggravation by exertion, breathing or posture and its association with other symptoms (dyspnoea, cough, palpitations, reflux) usually enable an early presumptive diagnosis to be made from a careful history. Pain may be clearly secondary to a lump or some other problem in the chest wall or to heartburn and water-brash (Ch 7). In this chapter causes of acute chest pain, presenting as the major or sole problem, are considered.

Clinical features

1 Angina pectoris, myocardial infarction and oesophageal spasm

Angina pectoris, myocardial infarction and oesophageal spasm are also discussed in Chapter 10.

5 Musculoskeletal disorders

The acute pain of rib fractures or muscular strain, of infiltrative bony tumours or of costochondritis (Tietze’s syndrome) is usually distinguishable by the history of injury, localisation of pain, exacerbation by movement rather than exertion and the characteristic local tenderness on palpation and compression. Pain and tenderness over costochondral joints and the xiphoid process often follow muscular exertion or repetitive work involving lifting the arm above the head.

Diagnostic plans

Chest X-ray

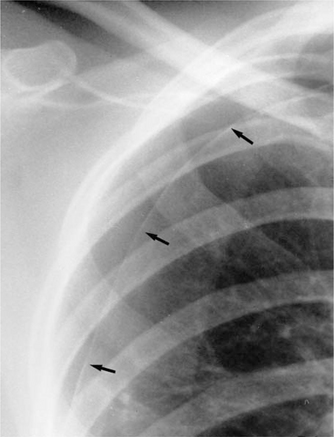

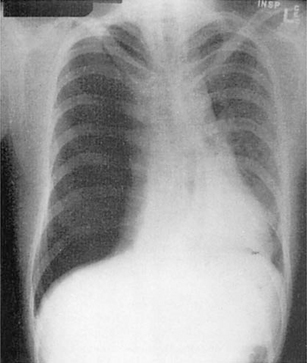

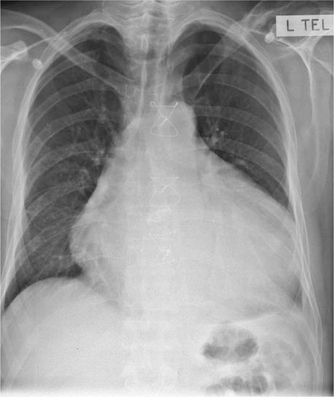

Chest X-ray will often be diagnostic. Films must be taken in the erect position to distinguish small apical pneumothoraces (Fig 4.1). Tension pneumothorax (Fig 4.2) will be accompanied by mediastinal displacement; pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade by an enlarged globular cardiac silhouette (Fig 4.3). Both tension pneumothorax and cardiac tamponade can progress rapidly to cardiac failure and death and sometimes no time is available for any investigations (e.g. a chest X-ray) prior to urgent relief of compression by aspirating the air or fluid. Mediastinal and subcutaneous air will indicate pulmonary or oesophageal rupture. With oesophageal rupture an associated pleural effusion, usually on the left, is common. Radiological signs of pulmonary embolus are usually nonspecific. Decreased pulmonary vascular markings may be apparent. A wedge-shaped density with an accompanying small effusion may be seen in pulmonary infarction.

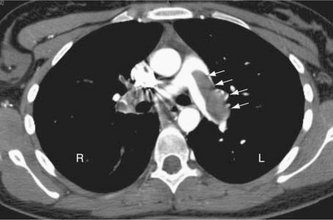

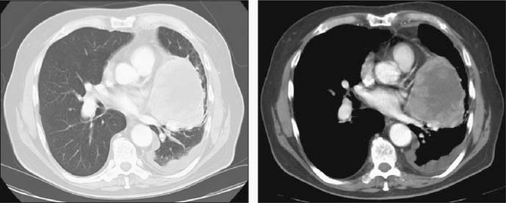

CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA)

This is the most reliable test for diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (Fig 4.4). Segmental pulmonary emboli are detected using helical CT of the pulmonary circulation with a single breath hold.

Treatment plans

3 Pleurisy and pneumonia

Patients with pleurisy complicating acute or chronic bronchitis or pneumonia are treated with antibiotics and intensive chest physiotherapy. Respiratory failure may occur and will require intensive care in hospital (Ch 12).

4 Pulmonary embolus

Depending on the size of the embolus and condition of the patient, anticoagulation with heparin, thrombolytic therapy with streptokinase or tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) or surgical embolectomy may be required. Treatment of postoperative pulmonary embolism is considered in Chapter 11.

4.3 Pleural effusion

Investigations

Chest X-ray (Fig 4.5) will determine the size of the effusion and may reveal underlying lung disease. CT scanning will also reveal significant intrathoracic disease. Diagnostic pleural aspiration will reveal the nature of the effusion based upon its appearance, cytological, microbiological and biochemical analysis. Pleural biopsy should be performed if the diagnostic pleural aspiration is unsuccessful or non-diagnostic. A malignant process leading to a pleural effusion requires adequate staging prior to the commencement of therapy.

4.4 Chronic cough and haemoptysis

Cough is usually a protective result of inflammatory, chemical or mechanical stimulation of cough receptors within the lungs. Coughing is also under voluntary control and may occur as a nervous habit in the absence of stimulation of receptors in the tracheobronchial tree. The cough reflex is mediated through the cough centre in the medulla, via the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. Coughing may sometimes be induced by stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve in the external ear by wax, inflammation or foreign body.

Clinical features

2 Carcinoma of the lung

Two thirds of lung cancers are located centrally near the hilum and one-third peripherally. About one-third are squamous cell (epidermoid) carcinomas (Table 4.5). Chronic cough is the most common form of presentation of carcinoma of the lung and may present as a change in the pattern of a longstanding cough (alteration in frequency, severity or sputum production). The cough may also begin abruptly resembling foreign body obstruction or masquerade as an acute pneumonia that is slow to resolve. The onset is usually insidious, but when symptoms become established the principal complaints are productive cough, wheeze and haemoptysis.

| Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Non-small cell lung cancer | |

| Squamous cell (epidermoid) carcinoma | 35 |

| Large cell carcinoma | 20 |

| Adenocarcinoma* | 10 |

| Mixed (adenosquamous) | 5 |

| Small cell lung cancer | 30 |

* Only type unrelated to smoking

Asymptomatic patients often present because of an abnormal chest X-ray, with either a coin lesion or solitary pulmonary nodule (Table 4.6) or a mediastinal mass. There may be no physical signs on examination — or a variety of findings that include cervical lymphadenopathy, pulmonary collapse or consolidation, pleural effusion, localised wheeze or other signs of metastatic disease such as hepatomegaly. Tumours involving the apex of the lung may cause Pancoast’s syndrome because of involvement of the brachial plexus, sympathetic chain and sometimes destruction of ribs. Symptoms are pain and loss of strength in the arm and Horner’s syndrome on the involved side.

Table 4.6 Causes of coin lesion in the lung on chest X-ray

| Disease | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Bronchogenic carcinoma or bronchial adenoma | 50 |

| Metastatic carcinoma | 10 |

| Benign tumours (hamartoma or fibroma) | 10 |

| Granuloma (tuberculosis and histoplasmosis) | 20 |

| Miscellaneous (bronchogenic cyst, pulmonary sequestration, A-V malformation, pulmonary lymph node, residual pneumonia, pulmonary infarct, rheumatoid nodule, infected bulla, sclerosing haemangioma) | 10 |

Diagnostic plans

Sputum cytology may reveal atypical cells consistent with lung carcinoma

Imaging

Chest X-ray. Posterior–anterior and lateral chest X-rays should be performed on all patients and compared with previous X-rays, if available (Fig 4.6). The X-ray findings in lung cancer are classified into hilar or parenchymal lesions. Cavitation may be seen, as well as peripheral atelectasis, collapse, pneumonia, erosion and pathological fracture of ribs, raised diaphragm, pleural effusion and hilar lymphadenopathy. The trachea may be compressed or deviated. The X-ray signs found after foreign body inhalation vary from normal to those of lobar collapse, pneumonia, abscess and empyema. The foreign body itself may be radio-opaque. Pulmonary tuberculosis nearly always involves only the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and the superior segment of the lower lobe. The lesions vary in appearance and include solid shadows, coin lesions, cavitation, fibrosis with streaking, spotted calcification, effusion and miliary change.

CT scan of the chest and upper abdomen is most useful for defining mediastinal lesions, detecting additional metastases and directing the needle for fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) studies (Fig 4.7).

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan allows the detection of regional lymph node and distant metastases. Up to 15% of patients thought to have surgically resectable disease have evidence of metastatic disease on PET scanning.

Endoscopic studies

Staging of non-small cell lung cancer is clinical and based upon descriptors of the size and location of the primary tumour (T), the spread to lymph nodes within the thorax (N) and to the presence or absence of distant metastases (M) (Box 4.2).

Box 4.2

TNM staging of lung cancer

TX — Positive malignant cytologic findings, no lesion observed

Regional lymph node involvement (N)

N1 — Ipsilateral bronchopulmonary or hilar nodes involved

TMN subgroups are grouped together into stages 0 to IV and these stages provide information about prognosis, allow a comparison of outcomes from different clinical series and also guide therapy (Boxes 4.3 and 4.4).

Treatment plan

4 Foreign body

Foreign bodies are removed by flexible fibre-optic or rigid bronchoscopy. Transbronchial drainage of pulmonary abscesses can also be performed.

4.5 Chest wall problems

These may affect any of the individual layers of the chest wall.

Clinical presentation and management plans

4 Costochondral swellings

The most common benign tumours are chondromas and osteochondromas, which present as swellings at the costochondral junction. They can show expansion of the rib with an intact cortex. Chondrosarcomas cause bone destruction. Progressive growth is an indication for biopsy.