CHAPTER 79 Chemical peels and dermabrasion

Physical evaluation

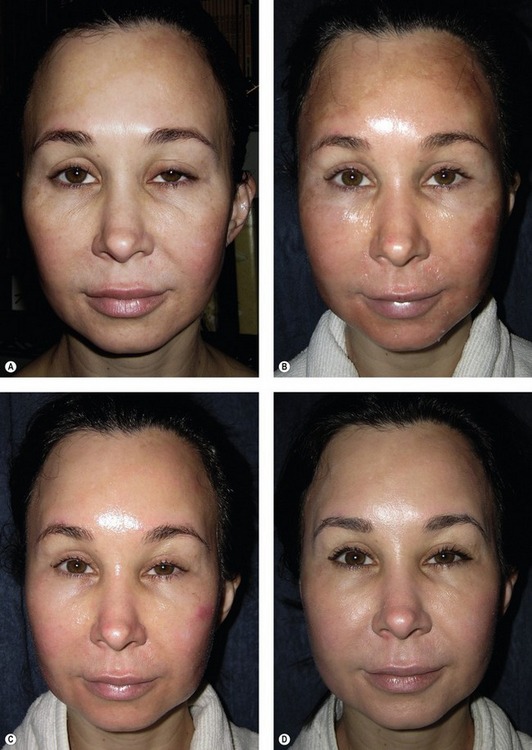

• Skin type is the most important factor. The Fitzpatrick classification (Table 79.1) identifies six skin types based on reaction to sun exposure; the lower the Fitzpatrick type, the less melanin in the skin. In general, patients with darker skin types have a greater tendency to develop post-treatment hyperpigmentation, while patients with light skin are more prone toward post-treatment hypopigmentation.

• Complexion (degree of pigmentation) determines the ability of the skin to withstand environmental injury.

• Skin thickness, pore size and sebaceous secretions influence pretreatment and safety margin.

• Degree and level of actinic damage (photodamage) influence treatment.

• Depth and location of wrinkling and gravitational changes must be considered.

• Hair and eye color is useful in the evaluation of resurfacing patients.

• History of herpes, poor wound healing, allergies, pigmentary problems.

• Patient lifestyle and acceptable downtime must be considered.

| Type | Color | Reaction to sun exposure |

|---|---|---|

| I | White | Always burns/never tans |

| II | White | Usually burns/tans with difficulty |

| III | White | Sometimes mild burn/average tan |

| IV | Moderate brown | Rarely burns/tans with ease |

| V | Dark brown | Very rarely burns/tans very easily |

| VI | Black | Never burns/tans very easily |

Data from Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol 1988;124:869.

Anatomy

Aging of the skin affects both the epidermis and dermis and is exacerbated by actinic damage. Aging causes epidermal hyperplasia, atrophy and dysplasia, producing an atrophic and flat epidermis. Dermal connective tissue shows progressive diminution with loss of much of the reticular dermis. Collagen fibers become degenerated and thickened. Reduction of the amount of collagen leads to thinning of skin. The dermis of actinically damaged skin exhibits elastosis, the presence of thickened, degraded elastic fibers. Separating the solar elastotic material from the epidermis is a thin zone of normal appearing dermis largely composed of collagen, called the Grenz zone. Additionally, aging causes loss of dermo-epidermal papillae and reduction in the melanocytes. These histological changes are responsible for the clinical signs of aging and sun damage including wrinkling, laxity, and pigment changes. Cutaneous resurfacing is intended to reverse these changes.

Technical steps

Trichloroacetic acid (TCA)

Phenol

The Baker–Gordon formula is the standard phenol formula. It consists of 3 mL USP liquid phenol, 2 mL tap water, eight drops of liquid soap and three drops of croton oil (Table 79.2). Soap lowers the surface tension of the mixture and croton oil has been thought to act as a vesicant, increasing local inflammation and penetration of phenol. Water prepares a solution of 50% phenol concentration. It has been shown through histologic studies that the Baker–Gordon formula penetrates deeper than pure phenol (Stegman, 1980).

| 3 mL USP liquid phenol |

| 2 mL tap water |

| 8 drops liquid soap |

| 3 drops croton oil |

Data from Baker, TJ, Stuzin, JM, Baker TM. Facial skin resurfacing. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing, 1998.

Hetter (2000) varied the concentration of croton oil and demonstrated that it was the concentration of croton oil and not the concentration of phenol that was the factor that controlled depth of penetration. He asserted that phenol is simply the carrier. Minute variations in the concentration of croton oil are critical to the outcome of the peel. The different proportions according to depth of peel desired and anatomic site are summarized in what Hetter calls “the heresy phenol formulas”. As a result of this work, phenol peels are probably more properly referred to as “phenol–croton oil” peels.

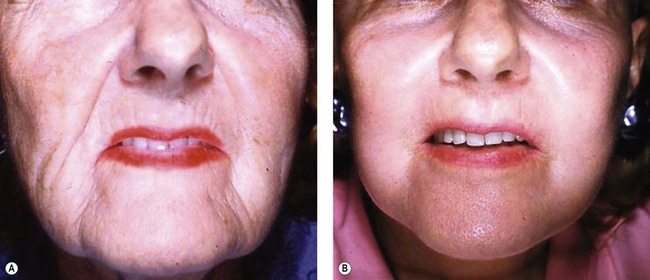

Dermabrasion

Dermabrasion, which was developed in the 1950s, mechanically abrades the epidermis and upper portion of the dermis. It is technique dependent and the depth can be precisely controlled. The epidermis is entirely obliterated and there is partial removal of the dermis, which undergoes incomplete regeneration. Both coarse and fine wrinkling can be treated with dermabrasion. Wrinkles can be lowered and smoothed mechanically. For resurfacing, dermabrasion is most useful for perioral lines and particularly those of the upper lip. Baker (1998) describes the current technique of dermabrasion and reviews the various adjuncts, instruments, indications, contraindications, and complications of the procedure.

Dermabrasion patients may receive premedication and/or regional nerve blocks may be used. The hand-held dermabrader is motor-driven and operates at 12,000–15,000 rpm. There is a wide variety of diamond-tipped burrs, differing in shape, size and coarseness. Protection against aerosolized particular matter must be taken. Wrinkles are marked before infiltration of anesthesia and regions are treated according to anatomic subunits. The handpiece should be kept moving, with light pressure applied. The edges of treated areas are feathered to blend with those not treated. Providing treatment to the proper depth is important. After the epidermis is removed, the pink epidermal–dermal junction is encountered. As treatment continues, fine punctate bleeding indicates the level of the papillary dermis. At the papillary–reticular junction, bleeding is increased and the surface becomes rougher, indicating the endpoint of treatment for most patients. Following treatment, the entire face is covered with gauze soaked in lidocaine with epinephrine to provide both anesthesia and hemostasis. Once bleeding has stopped, ointment is applied and the treated area either covered with petroleum or xeroform gauze, or is left uncovered. There appears to be neocollagen formation following dermabrasion.

Complications

The most serious, but rare, complication of chemical peeling and dermabrasion is scarring. In general, the deeper the peel, the higher the risk of scarring. An increased risk of scarring is associated with injury to the deep reticular dermis and is most often seen in the perioral and mandibular areas. Full thickness injury to the skin cannot heal by re-epithelialization and permanent scarring is inevitable. Also, previous use of isotretinoin (Accutane) may lead to hypertrophic scarring. Scars are usually preceded by persistent erythema and should be treated with topical corticosteroids, which can reverse the process and prevent a scar from forming. Intralesional corticosteroids and/or silicone pressure dressings may be used and in severe cases, surgical revision may be necessary.

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Different resurfacing techniques produce similar injury and thereby similar results.

• Efficiency of healing and re-epithelialization is related to the concentration of adnexal structures which decreases with increasing depth of injury.

• Aesthetic benefit and complication rate are directly related to the depth of injury.

• Choice of treatment is multifactorial.

• The goal of any resurfacing treatment is removal of abnormal tissue, stimulation of new collagen and elastin, and formation of new epidermis with overall rejuvenation of the skin.

Pitfalls

• There is no perfect resurfacing technique.

• Chemical peeling and dermabrasion are very technique dependent.

• Numerous factors affect penetration and depth of injury.

• Chemical peels and dermabrasion can be complicated by variable results.

• Risk of prolonged erythema or pigment loss is directly proportional to the depth of resurfacing.

Summary of steps

1. Pretreatment regimens to minimize adverse pigmentation changes.

2. Prior to treatment, the skin is degreased with acetone and/or alcohol.

Trichloroacetic acid (TCA)

3. Sedation is usually not necessary with 35% TCA.

4. TCA solution is applied regionally to each facial unit with brush-like strokes.

5. Frosting is the key to judging the depth of the peel.

6. Once the desired degree of frosting occurs, the acid is washed with water.

7. If the frost is not deep enough, it is appropriate to retouch areas.

8. During the entire peeling process, a fan can be used to aid in patient comfort.

Phenol

9. The Baker–Gordon formula is the standard phenol formula.

10. The phenol solution is applied with a contact tip applicator.

11. The skin frosts a grayish white color and a burning sensation is experienced.

12. Small subunits are peeled at 15- to 20-minute intervals.

13. Either tape or ointment is applied to the treated areas.

Dermabrasion

14. Premedication and/or regional nerve blocks are used.

15. Wrinkles are marked before infiltration of anesthesia.

16. Regions are treated according to anatomic subunits.

17. Handpiece is kept moving, with light pressure applied.

18. Edges of treated areas are feathered to blend with those not treated.

19. Increased bleeding indicates the endpoint of treatment.

20. Following treatment, the areas are covered with gauze soaked in lidocaine with epinephrine.

21. Once bleeding has stopped, ointment is applied with or without petroleum gauze.

22. After resurfacing, routine skin care can be resumed, including the use of cleansers, moisturizers and sunscreens.

Baker T, Stuzin JM, Baker TM. Facial skin resurfacing. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 1998.

Baker TJ, Gordon HL. The ablation of rhytides by chemical means: A preliminary report. J Fla Med Assoc. 1961;47:451.

Baker TJ, Gordon HL. Chemical face peeling and dermabrasion. Surg Clin North Am. 1971;51:387.

Fitzpatrick RE. Resurfacing procedures: how do you choose? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:783–784.

Hetter GP. An examination of the phenol-croton oil peel: Parts I–IV. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:227–248.

Kligman AM, Baker TJ, Gordon HL. Long-term histologic follow-up of phenol face peels. Plast. Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:652.

Perrotti JA. Cutaneous resurfacing: chemical peeling, dermabrasion and laser resurfacing: Grabb and Smith’s plastic surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

Stegman SJ. A study of dermabrasion and chemical peels in an animal model. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:490.