Chemical dependency in anesthesia personnel

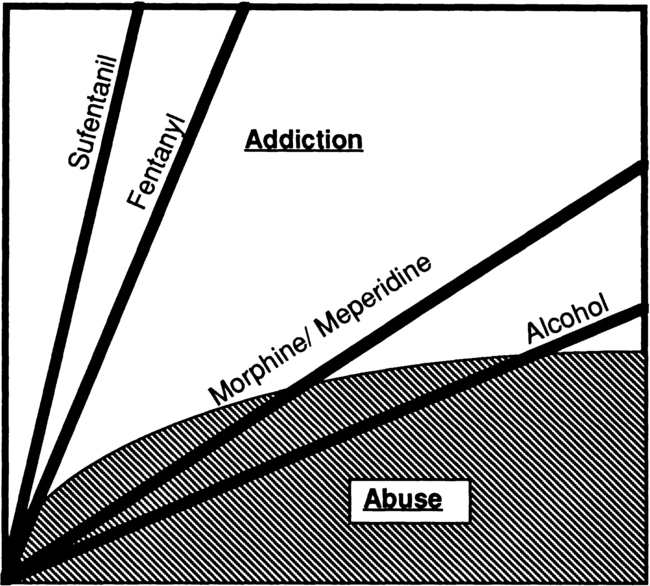

Fentanyl, available as a street drug, is considered by addiction medicine specialists to have an addictive potential similar to that of “crack” cocaine. It carries the risk of extremely rapid addiction (Figure 254-1). This rapid effect is in contrast with that of ethanol or even other opioids, such as morphine or meperidine, for which a longer period of abuse is typically required before psychological and physical addiction occur.

Recognizing impairment in a colleague

Chemical dependency threatens the career and, possibly, the life of an impaired colleague and the lives of patients under his or her care. Therefore, it is imperative that telltale signs of addiction be recognized and treated, not ignored (Box 254-1). These signs, typically subtle, may not be apparent in the workplace until the addictive illness is relatively far advanced. Instead, the afflicted individual may appear to function well in the workplace while his or her family life and social functioning may be in a state of chaos. In the case of opioid addiction, this behavior may be an attempt to preserve both career and access to the needed drug. It is interesting to note that, although the incidence of opioid abuse by anesthesia providers, even while on duty, is known to occur with distressing frequency, documented harm to patients by impaired caregivers is rare.