190 Chemical Burns

• Copious, immediate irrigation is the most important treatment of chemical burns.

• Elemental metal burns are the only chemical burns that should not be irrigated with water. Instead, wipe the material off with dry gauze and protect yourself from contamination.

• Identifying the cause of a chemical burn may be difficult, but the use of external resources (material safety data sheet, paramedics, employers, poison center) will help characterize the agents.

• Patients who exhibit no further signs of systemic toxicity may require only a chemistry panel and an electrocardiogram to complete an assessment.

• Patients with hydrofluoric acid burns require topical treatment with calcium gluconate gel, local infiltration of calcium gluconate, or for the most severe cases, intraarterial administration of calcium gluconate.

Epidemiology

Chemical burns are an unusual type of burn because the tissue injury is caused by the chemical reaction rather than by thermal damage. Chemical burns are common at work, at home, or in association with hobbies. One study found 22% of all pediatric burns to be a result of chemical burns,1 whereas other studies have estimated the percentage of admitted burned patients with chemical burns to be between 10% and 14%.2,3 With the recent concerns over terrorism, chemical agents have been emphasized as a possible method of attack, so knowledge of chemical burns is critical in the education of today’s emergency physicians. In addition, failure to recognize chemical burns or to treat them appropriately can have a detrimental impact not only on patients but also on care providers.

Pathophysiology

Different chemical burns affect tissue by different mechanisms. Table 190.1 provides different categories of chemical agents and their mechanism of tissue damage. Most chemical burns involve skin; accordingly, knowledge of skin anatomy is key to understanding the pathophysiology of various chemical burns because of the link to treatment. A direct injury results when the epidermis is penetrated. Systemic absorption is possible once the injury extends through the dermis.

Table 190.1 Chemical Agents and Their Mechanisms of Tissue Damage

| TYPE OF CHEMICAL AGENT | MECHANISM OF TISSUE DAMAGE | EXAMPLE OF AGENT |

|---|---|---|

| Acids | Coagulative necrosis | Sulfuric acid |

| Alkali agents | Saponification and liquefactive necrosis | Calcium hydroxide |

| Desiccants and vesicants | Dehydration of cells through exothermic reactions, release of amines within cells | Nitrogen mustards |

| Oxidizing and reducing agents | Denaturing of proteins and direct cytotoxic effects | Bleach |

| Protoplasmic poisons | Formation of salts with cellular proteins | Picric acid |

Hazardous Materials

The U.S. Department of Transportation requires color-coded identification of the type of material transported. These identifying codes are widely used. Additionally, a standard four-number code should be present to identify or characterize the agent more specifically. Figure 190.1 indicates the general categories and identifying colors, which include the following:

• Nonflammable gases (solid green)

• Flammable liquids (solid red)

• Flammable solids (white and red stripes)

• Oxidizers and peroxides (solid yellow)

• Poisons and biohazards (solid white)

• Radioactive materials (half white, half yellow, with a black radiation symbol)

Treatment

Elemental Metals: Do Not Irrigate

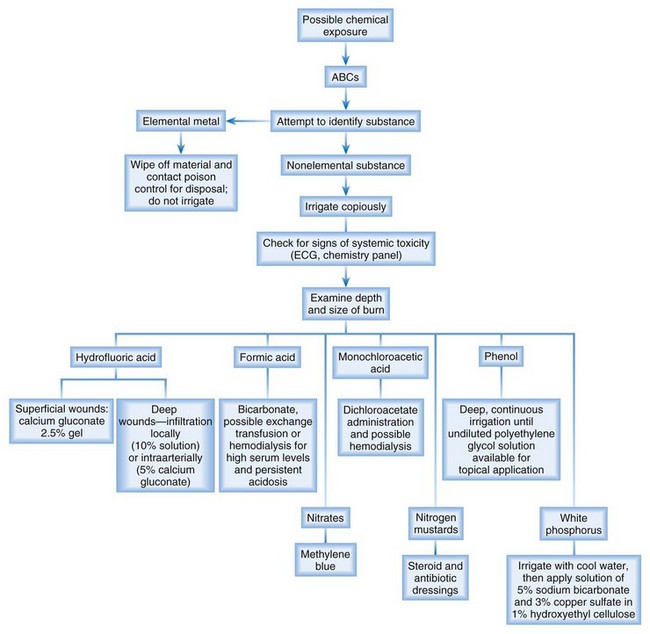

Figure 190.2 is an algorithm for the management of patients with possible chemical burns.

Ocular Exposure

Ocular chemical burns are highly morbid injuries. The initial therapy of copious irrigation cannot be emphasized enough. Lid retraction with eversion is a key procedure to remove all chemical particles. Testing for the continued presence of chemicals can be accomplished with pH paper, but it is important to wait a minimum of 5 minutes after irrigation to make sure that the pH of the irrigation fluid is not being checked. Patients with burns caused by certain chemicals may require admission for continuous irrigation. Any patient with ocular exposure that results in corneal burns (identified by fluorescein examination) should have an ophthalmology consultation. Other elements of the examination are similar to any eye examination and include visual acuity, slit-lamp examination, and visual field evaluation. Tap water is recommended as the initial irrigating agent (because it is the most easily obtained and time until irrigation is a key element), but normal saline, lactated Ringer solution, and buffered solutions all work effectively.4

Ingestions

Although discussion of the management of caustic chemical ingestion is beyond the scope of this chapter, two key concepts should be emphasized. First, the primary issue is maintenance of the airway. Second, the extent of burn is usually limited to the initial exposure, and decontamination of the gastrointestinal tract is difficult and not recommended; the only substance that has been suggested is water, but because of possible exothermic reactions resulting from attempted water irrigation, water decontamination of the gastrointestinal tract is controversial. Endoscopy is the only method for definitive assessment of the degree of injury, but the common complications of perforation and mediastinitis should also be assessed.5 Some recent studies suggest that not every patient with a chemical burn involving the esophagus requires endoscopy, but consultation with gastroenterology and toxicology is recommended.6

Directed Therapies

Specific agents are known to cause specific toxicities. If the substance is known, therapy should be directed against that toxicity (Table 190.2).

| AGENT | SPECIFIC TOXICITY | ADDITIONAL TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrofluoric acid | Severe hypocalcemia and continued liquefactive necrosis | Superficial wounds: calcium gluconate 2.5% gel Deep wounds: local infiltration (10% solution) or intraarterial injection (5% solution) of calcium gluconate |

| Formic acid | Severe acidosis | Bicarbonate administration, possible exchange transfusions or hemodialysis for high serum levels and persistent acidosis |

| Cement (alkali burn) | Persistent burns when exposed to water if not irrigated away completely | Thorough irrigation |

| Phenol | Systemic absorption causing central nervous system depression, coma, and death | Because a more dilute solution is absorbed more rapidly, deep, continuous irrigation is performed until undiluted polyethylene glycol solution is available for topical application; all other treatment is supportive for systemic symptoms |

| White phosphorus | Continued thermal burning resulting from burns on exposure to oxygen; systemic absorption causing acidosis and electrocardiographic abnormalities, possibly sudden death | Removal of as much phosphorus as possible through irrigation with cool water, then placement of a solution of 5% sodium bicarbonate and 3% copper sulfate in 1% hydroxyethyl cellulose |

| Elemental metals (sodium, potassium) | Exothermic reaction when exposed to water | Wiping away of material and contacting a poison control center for disposal instructions |

| Nitrates | Methemoglobinemia | Administration of methylene blue |

| Monochloroacetic acid | Systemic lactic acidosis | Administration of dichloroacetate and possible hemodialysis |

| Nitrogen mustards | Vesicle formation | Steroid and antibiotic dressings after copious irrigation |

Hydrofluoric Acid

Patients with mild, limited superficial exposure can be treated with topical calcium gluconate, which must usually be mixed in the emergency department by combining calcium gluconate powder with commonly available lubricant jelly. Affected fingers and hands can be placed in a medical glove that contains the solution.7

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Scenarios Suggestive of Specific Types of Chemical Burns

| Scenario | Suspicious Agent |

|---|---|

| Circumferential lower extremity burns above the sock line | Cement |

| Burn in a glass etcher | Hydrofluoric acid |

| Burn from fireworks | White phosphorus |

| Mass exposure (terrorist attack) | Nitrogen mustard |

1 Shah A, Suresh S, Thomas R, et al. Epidemiology and profile of pediatric burns in a large referral center. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50:391–395.

2 Dissanaike S, Rahimi M. Epidemiology of burn injuries: highlighting cultural and socio-demographic aspects. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21:505–511.

3 Wibbenmeyer LA, Morgan LJ, Robinson BK, et al. Our chemical burn experience: exposing the dangers of anhydrous ammonia. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20:226–231.

4 Kompa S, Schareck B, Tympner J, et al. Comparison of emergency eye-wash products in burned porcine eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240:308–313.

5 Duncan M, Wong RKH. Esophageal emergencies: things that will wake you from a sound sleep. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:1035–1052.

6 Betalli P, Falchetti D, Giuliani S, et al. Caustic ingestion in children: is endoscopy always indicated? The results of an Italian multicenter observational study. for the Caustic Ingestion Italian Study Group. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:434–439.

7 Bethel CA, Krisanda TJ. Burn care procedures. Roberts JR, Hedges J. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine, 4th ed., Philadelphia: Saunders, 2004.