18 Cheeks

Summary and Key Features

• The cheeks are important to communicating one’s age and are essential for smiling and laughing. Filling the cheeks reconstitutes a youthful appearance, and adds value to rejuvenation of other facial cosmetic units

• Anatomical borders are: the zygomatic arch, inferior orbital rim, lateral nose, nasolabial fold, and superior jawline

• Aging causes facial bone and soft tissue atrophy. It accentuates gravitational descent of the angle of the mouth and produces unattractive shadows. Lipoatrophy is associated with an unhealthy appearance

• Fat augmentation of the cheeks is a well-established technique. It offers excellent cosmetic results, but requires donor tissue and may not be long lasting

• Non-resorbable fillers provide long-term results, but have permanent risks

• Resorbable fillers are excellent options for cheek augmentation. They allow office-based procedures yielding natural results, and are increasingly long-lasting with minimal risks

Introduction

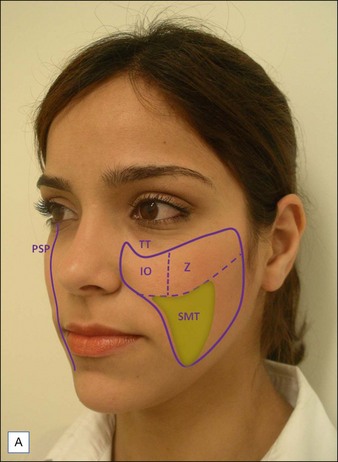

Each cheek is composed by the soft tissues covering the paramedian central facial skeleton (Table 18.1). The upper third of the cheek can be further divided into zygomatic and infraorbital subunits. The zygomatic subunit (cheekbone) represents the area of maximal projection of the cheek, called the malar eminence (Fig. 18.1A). The ideal malar eminence diffusely reflects light regardless of the angle one looks at the face. The cheeks work as a frame for adjacent cosmetic units such as the lips, eyes, and ears, allowing the observer to instinctively calculate cosmetic ratios related to those structures.

| Adjacent anatomical units | |

|---|---|

| Superior | Zygomatic arch; inferior orbital rim |

| Medial | Lateral nose; nasal–labial folds |

| Lateral | Preauricular sulcus |

| Inferior | Above the inferior jawline |

| Internal | Oral cavity, maxillary, and zygomatic bones |

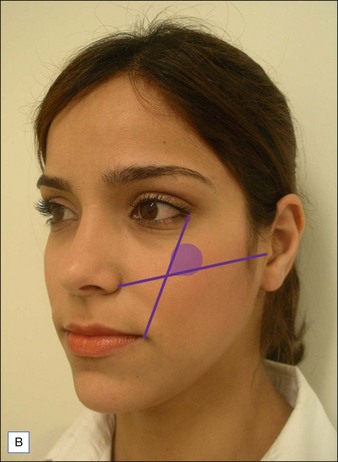

Although prominent cheekbones are usually associated with beautiful individuals, it is their relationship with the other facial structures that defines attractiveness. Several techniques are available to identify the optimal location of the malar eminence. Hinderer’s method is easy to obtain, helping to optimize filler placement when augmenting the cheeks. The ideal reflection of light should be kept in the upper outer quadrant formed by the intersection of two virtual lines: the first one runs from the lateral canthus of the eye to the angle of the mouth; the second one goes from the nasal crease to the tragus. Other aesthetic features of the cheeks are superficial textural homogeneity, lack of shadows, and smooth transition towards adjacent cosmetic units. Accordingly, the ideal parasagittal profile contour should have a smooth curvilinear shape from the eyelids to the cervical jaw angle (Fig. 18.1B).

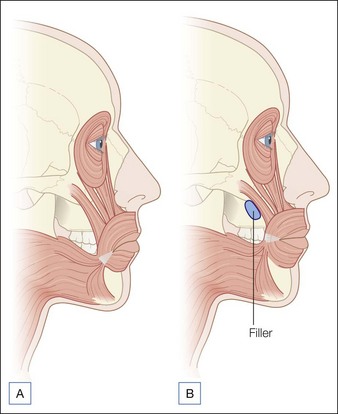

Aging of the mid-face is essentially caused by atrophy of the cheek bones and fat pads. In two areas these changes are striking: (1) within the submalar triangle (an inverted triangle defined medially by the nasolabial fold, superiorly by the malar eminence, and laterally by the anterior border of the masseter muscle) and (2) along the tear trough and eyelid / cheek junction. These changes lead to a deflated balloon pattern – folding the overlying skin. In addition, mid-face atrophy loosens the tissue surrounding the angle of the mouth, leading to a sad appearance (Fig. 18.2A). Filling the cheeks helps in restoring a gracious oral commissure (Fig. 18.2B).

Autologous fat transfer offers excellent overall cheek augmentation (Fig. 18.3). However, it requires harvesting of tissue, which may be difficult to obtain in the presence of generalized fat loss, as seen in some patients with drug-related HIV lipoatrophy. The duration of fat grafts is variable according to the technique used and recipient area (the cheeks usually have good retention rates); it also varies among individuals. Coleman reported that injecting small droplets of donor tissue, so that the whole graft receives enough nutrients, improves graft survival. Sterodimas et al found that adipose-derived stem cell-enriched lipografts may also prolong results. Despite those advances, liposculpture may not be attractive to individuals looking for office-based procedures.

Anatomical and technical considerations when filling the cheeks

Placement of fillers under the superficial musculoaponeurotic system provides significant expansion of the entire cheek unit, analogously to a pole that holds a tent up (see Fig. 18.2). This effect elevates the soft tissue around the corner of the mouth, slightly improving oral commissure grooves, possibly because the outer displacement of zygomatic muscles pulls the modiolus gently upwards. Likewise, filling the infraorbital area raises the levator of the upper lip muscle and associated fibrous tissues. Therefore, by working deeply in the mid-face we can expect natural improvement of marionette lines without directly injecting them. In addition to providing enough volumetric increase at rest, deep filling also reduces unattractive bulging of the augmented cheek when laughing.

Poly-L-lactic acid and hydroxylapatite

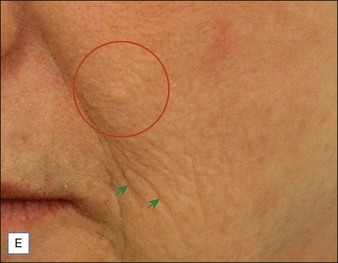

PLLA microspheres are US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for injection as diluted aqueous suspension. The total volume of the actual particles is negligible; however, with time they become encapsulated by fibrous tissue providing diffuse augmentation. This explains why it is necessary to perform several injections spaced months apart before significant results are appreciated (Fig. 18.4). It also explains why some patients are more responsive then others, since this neotissue formation varies among individuals.

The remarkable ability of PLLA to induce fibrous tissue formation has the additional effect of providing a tensing effect, which can be visually and palpably appreciated by thickening of the skin in the treated areas (Fig. 18.4E and F).

Volumizing hyaluronic acid

Adaption of pan-facial fat transfer techniques to these products has revolutionized facial volumetric lifting. Impressive office-based cheek augmentation can now be comfortably achieved during a single session using small amounts of local anesthesia (Fig. 18.5). Touch-ups and maintenance injections can be easily performed at variable intervals, providing additional improvement and extending results.

Blunt cannula approach

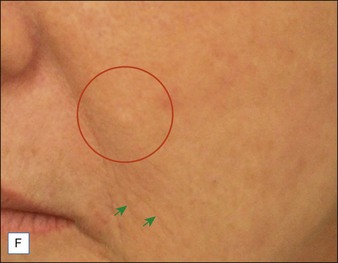

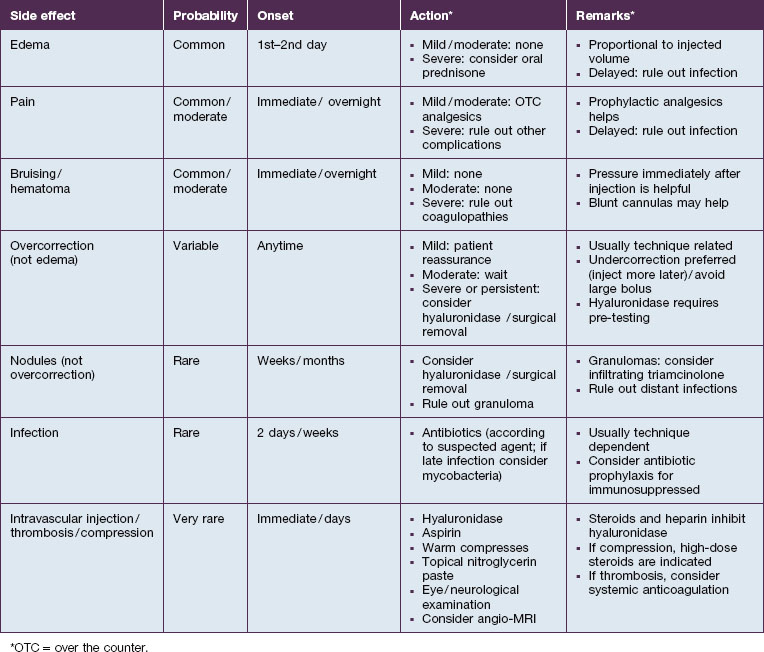

Filling along the orbital rim with traditional, less cohesive monophasic or containing smaller particle biphasic HA improves tear troughs. The skin covering the tear troughs is usually quite flaccid. Undercorrection of this area is highly advised to avoid stigmatizing protusion and producing a bluish discoloration (Tyndall effect). Using thin blunt cannulas is recommended – blood vessels in this region anastomose with retro-orbital ones. Everyone performing cheek augmentation should learn how to manage complications. Table 18.2 lists possible complications and management advice (see also the studies by Duffy and Hedén).

CASE STUDY 1

Large-particle NASHA™ (non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid) for Cheek Augmentation

A 75-year-old patient with a previous history of successful facial fat augmentation 4 years before (see Fig. 18.3) wished to complement the results with a less invasive procedure. She desired immediate results, but was not motivated by the inherent costs of using large amounts of hydroxylapatite or traditional hyaluronic acid (HA) products approved for facial use. More cost-effective alternatives were requested. Accordingly large-particle NASHA™, approved for breast augmentation in Europe and Brazil, was used for deep volumetric improvement of the mid-face and temples using the sharp needle approach described above for volumizing HA. In order to facilitate facial use, the HA was transferred from its original 10 mL syringe, under sterile technique, to 1 mL or 3 mL syringes by means of a Luer lock transfer. A total of 15 mL was subsequently injected with a 21 G needle. The patient was extremely satisfied with the results (Fig. 18.6). Anecdotally, over the past 2 years, this author has augmented the face of more than 20 patients, injecting up to 15 mL in a single session. Disclosure of the off-label indication was provided to every patient. This technique has yielded excellent cosmetic results, reducing costs without increasing side effects. These pilot cases warrant further investigation of the long-term applicability of using commercially available HA devices approved for other body parts to augment the face.

Figure 18.6 Same patient as in Figure 18.3, 4 years later. Off-label use of large-particle biphasic NASHA™ (non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid) (Macrolane™ VRF20, Q-med) for deep plane augmentation of the mid-face and temples (total bilateral volume of 15 mL) using a 21 G sharp cannula: (A) before, (B) after 5 days, and (C) after 5 months.

Burgess C. The evolution of injectable poly-l-lactic acid from the correction of HIV-related facial lipoatrophy to aging-related facial contour deficiencies. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2011;10(9):1001–1006.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A, Tezel A, et al. Volumizing with a 20-mg/ml smooth, highly cohesive, viscous hyaluronic acid filler and its role in facial rejuvenation therapy. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(suppl3):1886–1892.

Cattin TA. A single injection technique for midface rejuvenation. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2010;9(3):256–259.

Coleman SR. Structural fat grafting: more than a permanent filler. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;118(3 suppl):S108–S120.

Donofrio L, Weinkle S. The third dimension in facial rejuvenation: review. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2006;5(4):277–283.

Duffy DM. Complications of fillers: overview. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(11 pt 2):1626–1633.

Farhad BN. Facial aesthetics: concepts and clinical diagnosis. Chichester, UK: Wiley Blackwell; 2011.

Grover R. Optimizing treatment outcome with Restylane SubQ: the role of patient selection and counseling. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2006;26(suppl):S18–S21.

Haddock NT, Saaed PB, Boutros S, et al. The tear trough and lid / cheek junction: Anatomy and implication for surgical correction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;123(4):1332–1340.

Hedén P, Sellman G, von Wachenfeldt M, et al. Body shaping and volume restoration: the role of hyaluronic acid. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2009;33:274–282.

Hinderer VT. Malar implants for improvement of facial appearance. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1975;56(2):157–165.

Hirsch RJ, Brody HJ, Carruthers JD. Hyaluronidase in the office: a necessity for every dermasurgeon that injects hyaluronic acid. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2007;9(3):182–185.

Sterodimas A, de Faria J, Nicaretta B, et al. Autologous fat transplantation versus adipose-derived stem cell-enriched lipografts: a study. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2011;31(6):682–693.

Tobias GW, Binder WJ. The submalar triangle: its anatomy and clinical significance. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 1994;2(3):255–263.

Tzikas TL. A 52-month summary of results using calcium hydroxylapatite for facial soft tissue augmentation. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34(suppl 1):S9–S15.

Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R. Dermatological implications of skeletal aging: a focus on supraperiosteal volumization for perioral rejuvenation. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2008;7(3):209–220.