Chapter 13 Cheek Reconstruction

As with other areas of the face, the goal of cheek reconstruction is to create the “illusion of normality and the perception that all is as it was.”1 Normality on the cheeks is defined as symmetrical contour, color, and texture. The face is centered by the nose, eyelids, and mouth and framed by the forehead, chin, and cheeks. Thus, reconstruction on the peripheral cheeks will not be as apparent as on the central nose.

REGIONAL RECONSTRUCTION PRINCIPLES

Relaxed Skin Tension Lines

As discussed in Chapters 1 and 2, the relaxed skin tension lines (RSTL) generally run inferiorly and posteriorly over the surface of the cheek. If possible scars should be placed along these lines, particularly because these lines eventuate into wrinkle lines. Also scars are best placed in the lines and grooves of the periphery of the cheek in the cosmetic unit junctions, such as the preauricular fold, the melolabial fold, and the nasofacial angle. It should be noted, however, that flap incisions rarely spread when placed perpendicular to the relaxed skin tension lines. The reason for this is that in the cheek, although the inherent pull in the direction of the RSTL is more than the pull in the direction perpendicular to the RSTL, it is not very much more.

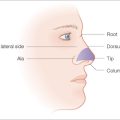

Surface Anatomy

The boundaries of the cheek are the preauricular crease, the superior border of the zygomatic arch and malar eminence, the inferior orbital rim, the nasofacial angle, the melolabial crease, and the inferior border of the mandible. The cheek may be roughly divided into seven somewhat overlapping and poorly demarcated subunit areas for the purpose of discussion. These seven areas include the following: medial, anterior (maxillary), infraorbital, zygomatic, buccal, preauricular, and mandibular. In each of these areas some flap types are more preferable than others. Many repairs in the cheek cross over and include more than one of these subunits. In some peripheral borders on the cheek, for instance the cheek and eyelid boundary, the border is best not transgressed by a single flap, but rather two flaps, one from the upper eyelid and one from the cheek so as to reestablish the boundary between the cheek and eyelid zones.1

Repairs on the face may be regional (eg, the whole cheek) as emphasized by Gonzalez-Ulloa2 or local (small flaps on only a portion of the cheek). The subunit principle applied by Burget and Menick3 to the nose is not as critical on the cheek because the subunits are less distinct. The only defining grooves are at the periphery of the cheek along the cosmetic unit junctions.

Subcutaneous Anatomy

Beneath cheek skin lies an investing fibrous layer, the submuscular aponeurotic system (SMAS). This layer lies between and is attached to the dermis above and the muscles below. Inferiorly SMAS is continuous with the platysma muscle.4 Deep to the SMAS lies the parotid gland and its duct, facial nerve branches, and the superficial muscles of facial expression. All these muscles are supplied by branches of the facial nerve (VII). The buccal branches of the facial nerve over the cheek ramify to such a great extent that any motor loss after reconstruction is usually temporary. The sensory supply to the cheek is mostly from the trigeminal nerve (V). The medial cheek is supplied by the second division (V2) through the infraorbital nerve. The lateral cheek to the mandible is innervated by third division (V3) of the trigeminal nerve. A small lower area of the posterior cheek near the lower ear is supplied by the anterior cutaneous nerve of the neck and by the great auricular nerve, which originates from the cervical plexus (C2, C3).

Special Anatomic Structures

There are two special anatomic structures in the cheek worth noting: the buccal fat pad and the parotid duct. The buccal fat pad is a large well-defined area in the central cheek with a large amount of fat. Its importance is that it is a good landmark for Stenson’s duct, which is the main drainage channel for the parotid gland. The duct courses over the buccal fat pad and descends anterior to it. If Stenson’s duct is transected and a flap repair done over the leaking area, there will be salivary drainage at the flap edge. Sometimes this will be difficult to see and is unavoidable. However, should this drainage occur, it will generally slow down and go away after a few months.5 If one sees the salivary leakage, recanalization of the duct may be attempted with a Silastic tube prior to flap repair; however, in the author’s experience this procedure is often unsuccessful.

Which Reconstructive Procedure

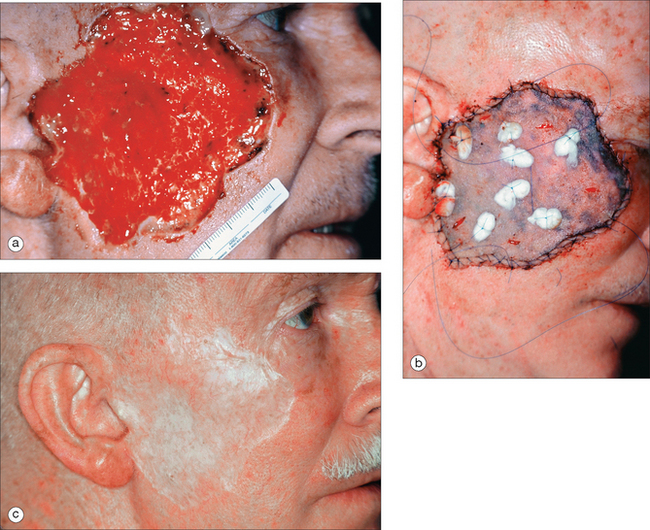

As mentioned earlier, skin grafts are generally not used on the cheek. A skin graft matches poorly with the surrounding and contralateral cheek skin in color, texture, type, and degree of hair growth. Furthermore, a skin graft often will not completely fill in a subcutaneous defect and provides less protection to underlying vessels and nerves than a skin flap. There are, however, two exceptions as to when a skin graft may be useful. First, to repair a defect that resulted from an excision of an aggressive tumor, e.g., angiosarcoma or sebaceous gland carcinoma. In this case, a split-thickness graft could be used to immediately repair the defect and to provide a window through which a tumor recurrence could be seen (see Figure 13.1). The second circumstance for doing a split-thickness graft would be to repair a very large defect, which could not be repaired in any other way. Prior to the development of large cheek flaps and cheek–neck rotation flaps, multistaged cheek rotation flaps6 or large skin grafts were commonly used to repair cheek defects.7

Reconstruction Philosophy

In reviewing the literature on cheek reconstruction, this author was struck by two trends. The first is that surgeons like to do one specific flap type for one specific defect at one time. This issue has been raised by other authors.1,8 Part of the reason for this approach has been that surgical training programs emphasize repairing the whole wound at one time; leaving part of the wound open is heresy. The second trend is that even medium-sized wounds on the cheek are repaired by rather large flaps extending into the neck and shoulder when these same wounds could have been closed with an equally good or better result by smaller, less complicated local flaps. The latter trend to do cervical neck or cervical pectoral flaps results in excessive surgery. This is not to say there is not a time and place for such flaps, but many of the case examples presented in the literature show medium-size wounds that could be repaired in other ways.9

FLAPS BY CHEEK REGION

Medial Cheek

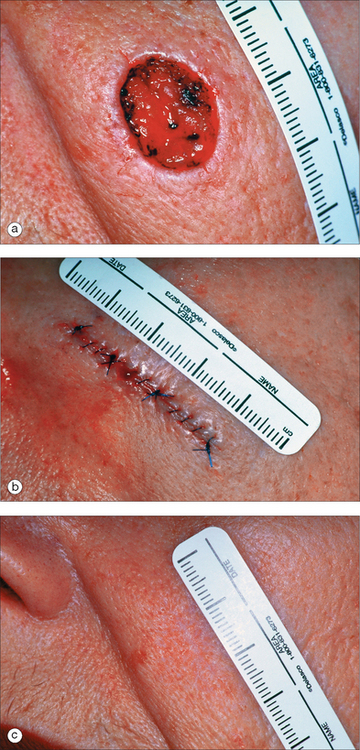

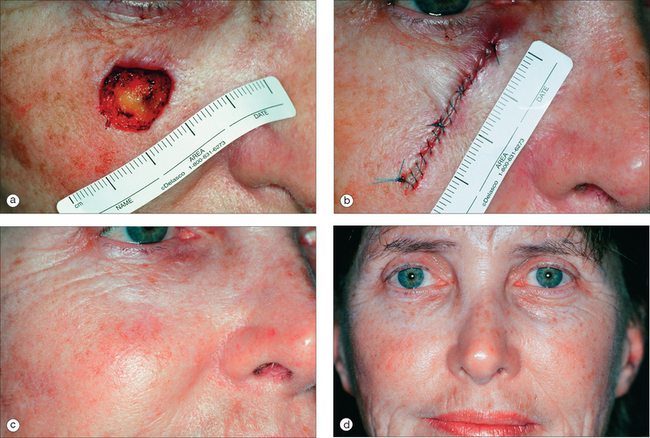

The medial cheek usually has significant skin laxity. If the wound is small to medium in size and its long axis is oriented vertically, a side-to-side repair may easily be done (Figure 13.2). If possible, repairs in this area are closed along the nasofacial angle or melolabial fold. Although some authors9 advise deep “periosteal” tacking sutures for side-to-side linear closures in the nasofacial angle, this author does not do this and feels it is usually unnecessary. For vertically oriented wounds on the medial cheek that cannot be closed without excessive tension on the wound edges, the rhombic transposition flap with a double Z-plasty is useful (Figure 13.3). This flap takes advantage of the inferior loose tissue available on the cheek. The double Z-plasty helps to increase the extension of the rhombic flap.11 The angulated incisions of the rhombic flap and Z-plasties generally blend in very well over time.

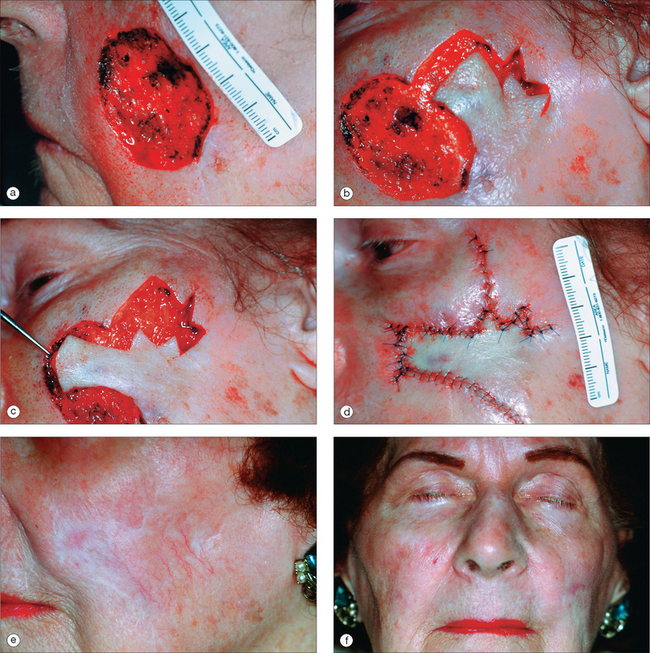

For a medial cheek wound with its long axis oriented horizontally, a side-to-side linear closure vertically oriented along the maximum skin tension lines would lengthen the suture line considerably. Therefore it might be best to consider a flap closure. There are three main flap choices for such a wound in this area: the subcutaneous island pedicle flap, the rhombic transposition flap (Figure 13.4), and the advancement flap with a back-cut (Figure 13.5). This author does not like the subcutaneous island pedicle flap in this location as this flap is often puffy, even many months later. When this happens, it is difficult to correct.10 Nevertheless it may be considered for small wounds just above or within the melolabial fold.

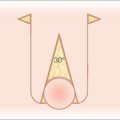

The rhombic transposition flap works well for medium-sized wounds in the medial cheek (Figure 13.4). As emphasized by Borges,12,13 it is important to design the rhombic flap so the base of the flap (that is, the base of the flap triangle) is perpendicular to the maximum skin tension lines on the cheek. Also, as Becker14 points out, the main flap tension is at the donor area, and these flaps on the cheek are generally laterally and inferiorly based. Cabrera and Zide15 further recommend that one base the rhombic flap inferiorly as this orientation tends to minimize the trapdoor effect, which may or may not be true.

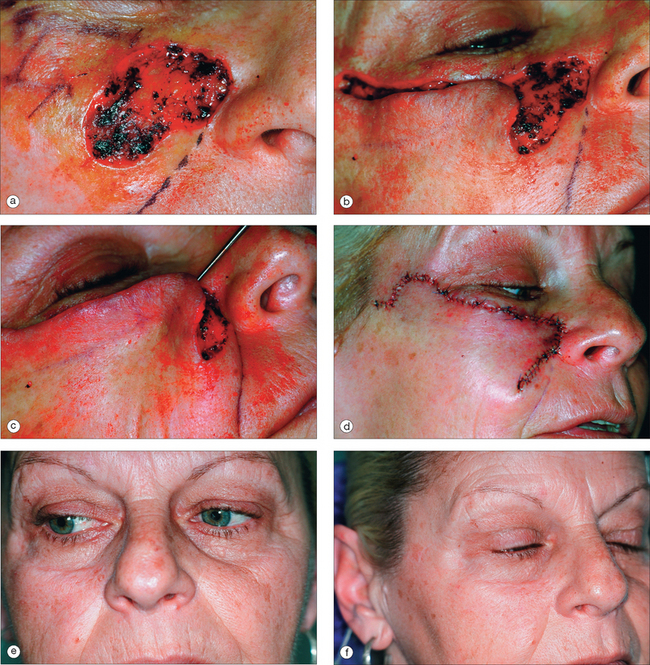

Horizontally oriented defects in the medial cheek are often best repaired with a rotation/advancement flap from the inferior direction (Figure 13.5). An incision line is made inferiorly along the melolabial crease line, often with a back-cut. The tissue is rotated and advanced superiorly and the back-cut triangle is removed. The incision down the melolabial crease with excision of a Burow’s triangle rather than a back-cut was described by Imre.16 This author prefers the back-cut triangle because there is less likelihood of nerve injury. One problem with the advancement/rotation flap with a back-cut is that medial canthal tenting may occur (Figure 13.6), particularly when this flap is used to repair horizontally oriented defects high in the medial cheek. To help prevent this problem, Jelks and Jelks17 advise deepithelializing the flap tip and fixing it to the medial canthal tendon. The tenting, if bothersome, may be released by a V-to-Y or Z-plasty. One should also employ a periosteal suture to hold the weight of the flap and decrease wound tension.

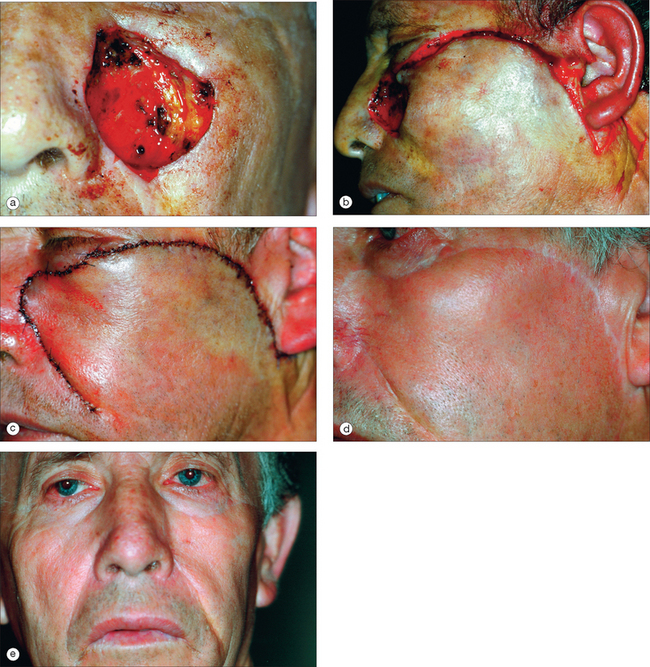

As the wound size increases, so does the complexity and difficulty of the flap. For large defects (especially those oriented vertically) in the medial or anterior cheek area, a whole cheek advancement/rotation flap may be created from the lateral cheek. Using the entire cheek lateral to a large defect as a single flap is considered by some physicians to be ideal because it is less noticeable compared to smaller flaps, which may cross the lines and natural creases of the face.9,18 Furthermore, this flap is a very vascular and therefore safe flap, which rarely has tip necrosis.

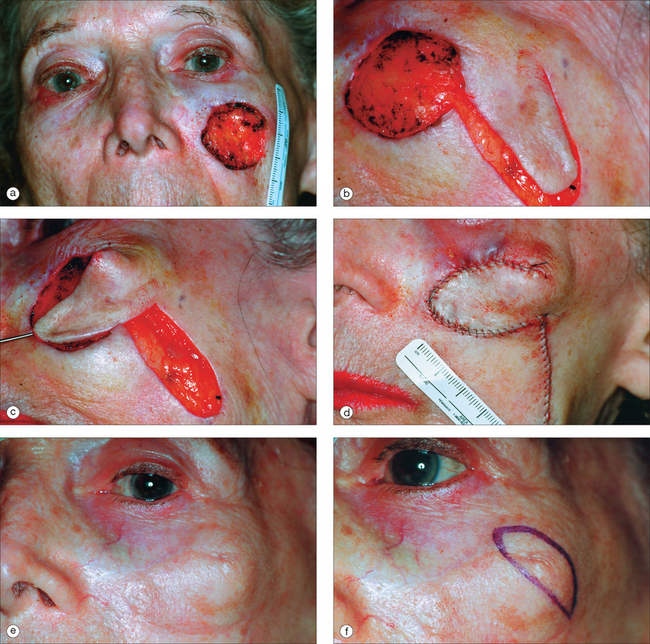

The cheek advancement flap has a medial inferior base and a forward and medial destination. The initial incision for a cheek rotation/advancement flap is made horizontally and laterally from the cheek defect extending on top of the orbital rim; as it progresses laterally at the point of the lateral canthus it is gently curved superiorly above the zygomatic arch to at least the level of the lateral canthus to decrease the chance of ectropion. This latter incision places the vector of any scar contraction in an upward posterior direction so that it will counteract any inferior pull on the lid. If this flap stops above the zygomatic arch in the temple, it is similar to the Mustarde flap used to close defects on the lower eyelid19 (Figure 13.7).

For very large defects of the medial or anterior cheek, the incision should be carried over the zygomatic arch and down the preauricular crease to a point 2 to 3 cm below the earlobe. Here a Burow’s triangle may be excised and hidden behind the earlobe20 (Figure 13.8). The flap is then rotated medially as it is advanced superiorly. It is critical to place tacking sutures along the lateral and inferior lateral orbital rim and the malar eminence to support the heavy flap and prevent ectropion. It is also important to thin the subcutaneous tissue along the superior flap border to match the skin thickness of the lower eyelid.

For large defects in the medial or anterior cheek, some authors9,21 prefer the cheek–neck (cervical facial) rotation flap. The flap incision on the cheek is similar to that of the cheek rotation flap just described. The incision follows the orbital rim laterally and at the lateral canthus is arched superiorly. The incision is continued posteriorly along the temporal hairline and preauricular crease. At the inferior lobule of the ear, the incision is then continued either inferiorly and anteriorly into a neck crease along the sternocleidomastoid muscle or posteriorly around the lobule and along the lateral inferior hairline.22,23 The extended incisions allow recruitment of tissue from the neck and retroauricular areas. Undermining is done in the mid-subcutaneous level (the face lift plane) with sufficient fat maintained to ensure adequate blood supply and adequate tissue thickness. As the flap is rotated, tacking sutures are placed into the deep tissues of the medial and lateral orbital rim to prevent inferior lid displacement. Tacking sutures are also advisable along the line between the lateral eyebrow and the superior attachment of the ear.24 Even though this flap may extend over the entire cheek, drains or suction catheters are rarely needed.25

For even larger defects on the medial and anterior cheek, the incision may be carried further down the neck to recruit even more tissue. Instead of bringing the incision anteriorly into a neck crease, as in the cervical facial rotation flap, the incision continues along the posterior border of the trapezius muscle and then medially at the end of the clavicle either along the clavicle or more inferiorly into the pectoral chest (cervicopectoral flap).26 If one makes the incision on the posterior border of the trapezius muscle there will be little likelihood of scar contracture or hypertrophy. Although the cervicopectoral flap has been considered a safe flap, some authors would disagree, particularly if the flap is under considerable tension.

As an alternative to basing the cheek advancement/rotation flap medially, some authors15,27–29 have suggested a laterally based cheek advancement/rotation flap in which an incision is made down the melolabial fold and onto the neck. This flap would mostly advance tissue superiorly with little rotation (thus the name the “hike flap”). Most of the blood supply to this latter flap would come from branches of the facial artery as it crosses over the inferior border of the mandible, where it can be palpated. In addition if one includes the platysma muscle in the flap, the blood supply will be further enhanced.30 However, because of the forces of gravity on this flap, great care needs to be taken to carefully tack the flap superiorly along the orbital rim to prevent ectropion.

Problems that can occur with large advancement rotation flaps on the cheeks include anterior transfer of hair-bearing tissue, which may be obvious in men, and ectropion. Therefore, it is important to fastidiously tack these flaps to underlying deep tissue in the zygomatic region. Also, if the wound edges are not carefully everted, the scar line may be easily seen (Figure 13.8d).

Anterior Cheek

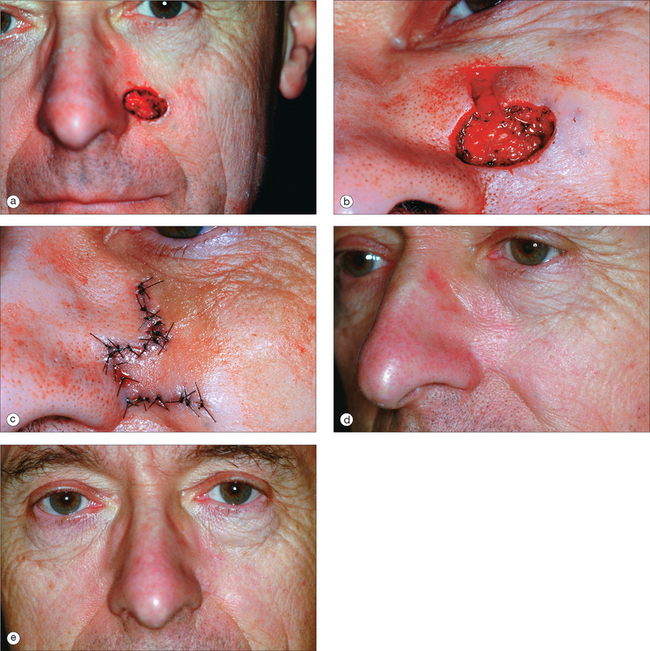

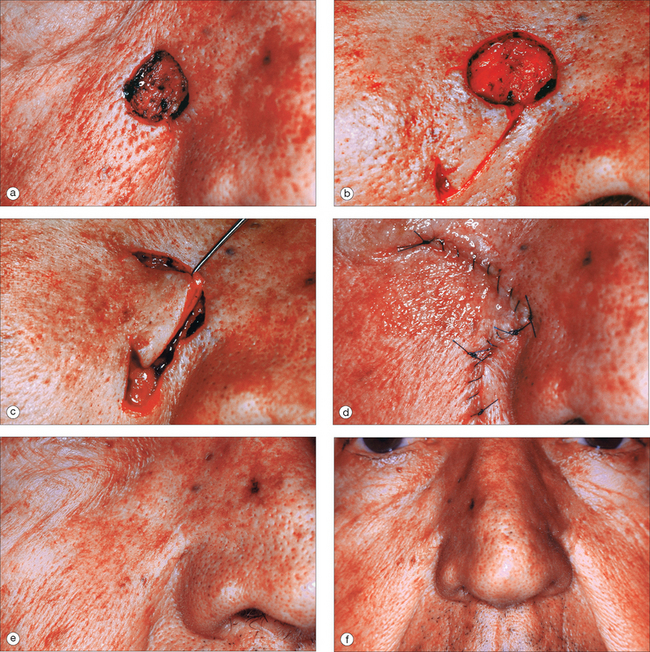

A defect on the anterior cheek can be closed with a side-to-side closure if small (Figure 13.9). For medium-sized defects the rhombic flap (Figure 13.10) and the rhombic flap with two Z-plasties is useful (Figure 13.11). For large defects, a single lobe transposition flap may be considered (Figure 13.12). The flap may be superiorly based as shown in Figure 13.12 or inferiorly based.10,15 Also, as on the medial cheek, a cheek rotation advancement flap may be considered, especially if the defect is large.

Malar Cheek

If the wound is small in this area, a Burow’s wedge advancement flap may be done. An incision is made laterally and the Burow’s triangle taken out lateral to the lateral canthus.31

Preauricular Cheek

Fortunately in this area, even large wounds can often be closed side-to-side. The rotation advancement (or the Burow’s wedge advancement) flap may be useful for small or medium-sized wounds in this area. For the latter flap, an incision is made inferiorly along the preauricular crease and a Burow’s triangle removed inferior and posterior to the earlobe. The flap is advanced superiorly. The Burow’s wedge advancement flap helps to preserve the cosmetically significant preauricular hairless area in men. Occasionally large preauricular wounds may be closed with a transposition flap. Generally the rhombic flap is inferiorly based.

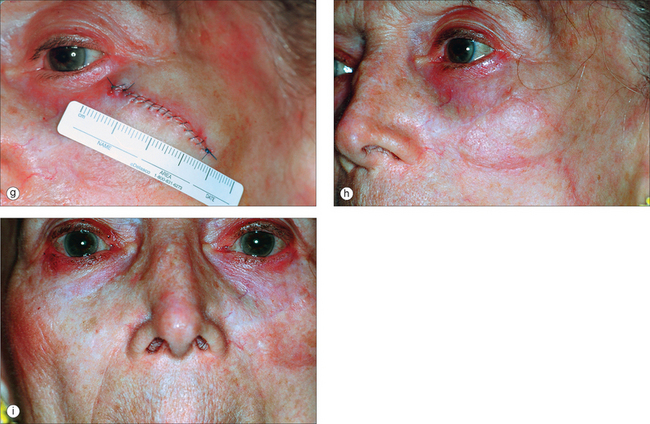

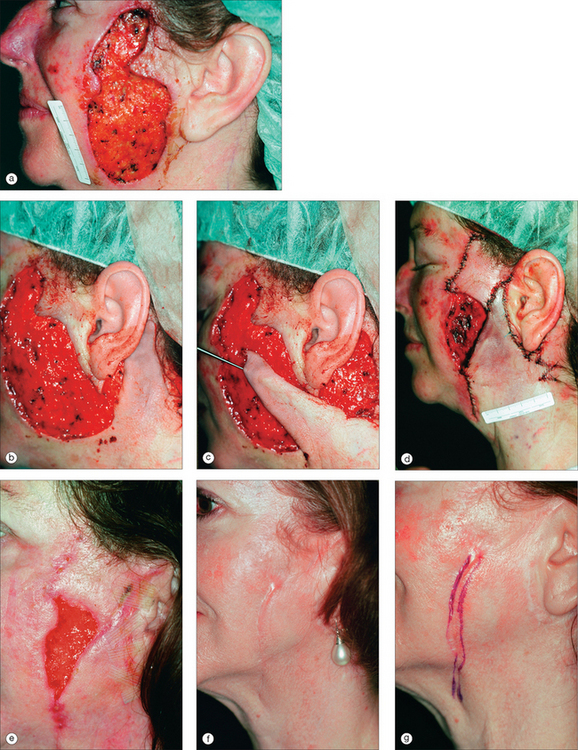

Very large wounds in the preauricular cheek may be re-paired with a cervical neck flap from below or a postauricular banner transposition flap32 (Figure 13.13). The posterior auricular banner transposition flap uses non-hair-bearing skin. An incision is made posterior to the earlobe superiorly along the postauricular sulcus; it is then arched superiorly and descends along the lateral posterior hairline. It utilizes the thin skin overlying the superficial cervical fascia covering the sternocleidomastoid muscles and the posterior auricular muscles. The base of the flap is posterior to the angle of the mandible and over the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The platysma muscle is present at the inferior and anterior portion of the flap base. The flap is richly vascularized in its subdermal plexus by vessels originating in the thyroid branch of the external carotid artery. Also, there are muscle perforators supplying the flap after coming through the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The dissection is done inferiorly above the platysma so that the cervical and marginal mandibular branches of the facial nerve are not injured. The posterior auricular flap is transposed over the ear to the preauricular cheek.

COMPLICATIONS

Eyelid Swelling

Perhaps the most common problem after cheek repairs, especially on the anterior and medial cheek, is eyelid swelling. This problem occurs particularly in the elderly. The lymphatic drainage occurs laterally and inferiorly on the cheek. As the cheek is pulled tight to close a wound, the tension creates a temporary damming effect and the eyelid lymphatics cannot drain normally. Usually, the patient will first notice eyelid swelling the morning after surgery. It will be worse on the second morning after surgery and then generally regresses so that the swelling is gone by the time of suture removal. It is wise to inform patients of the likelihood of eyelid swelling. Whether it can be diminished by use of a cold pack has not been shown but some physicians believe this to be true. Occasionally some eyelid edema may be long-standing following incisions made along the cosmetic unit junction between the lower eyelid and cheek.

Flap Necrosis

Patients on warfarin (Coumadin) are more likely to show flap necrosis. Smoking is also commonly thought to contribute to flap necrosis. However, it is only high levels of smoking (greater than one pack/day) that have been shown to have a significant effect.33

Ectropion

Lid displacement may occur because of edema, lid ptosis, flap tension, and denervation of the orbicularis oculi muscle. This is generally prevented by using tacking sutures and by ensuring a high arc lateral to the lateral canthus for cheek rotation flaps. The lateral superior border should be above the lateral canthal-helical root plane.8 If an ectropion persists after cheek surgery, it may be necessary to perform a canthopexy or place a full-thickness skin graft into the lower eyelid between the flap and lid margin to correct the problem.

Parotid Fistula

Occasionally when operating beneath the parotid fascia, the parotid duct may be nicked or transected. If this occurs, salivary gland leakage occurs. There are several possible treatment options, which include cannulation with parotid duct repair, duct ligation, tympanic neurectomy with or without chordi tympani section, irradiation of the gland, and even superficial parotidectomy. However, the best course of action is often to wait. In a series of cases of parotid duct and gland injury with salivary leakage, all cases treated conservatively dried up within a short period of time, usually in 3 to 5 weeks.5 It may be possible to prevent a parotid fistula by suturing SMAS over a parotid defect.34

Hypertrophic Scarring and Keloid Formation

These problems are rare on the cheek. However, when this occurs, usually one or two separate injections of up to 10 mg of triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) generally resolves the problem. Intralesional 5-Fluorouracil injections and pulsed-dye laser treatments have also been shown to be effective in the treatment of hypertrophic scars.

1 Dzubow LM, Zack L. The principle of cosmetic junctions as applied to reconstruction of defects following Mohs surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:353-355.

2 Gonzalez-Ulloa M, Castillo A, Stevens E, et al. Preliminary study of the total restoration of facial skin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1954;13:151-161.

3 Burget GC, Menick FJ. Submit principle in nasal reconstruction. Plast Reconst Surg. 1985;76:239-247.

4 Thaller SR, Kim S, Patterson H, Wildman M, Daniller A. The submuscular aponeurotic system (SMAS): a histologic and comparative anatomy evaluation. Plast Reconst Surg. 1990;86:690-696.

5 Landau R, Stewart M. Conservative management of post-traumatic parotid fistulae and sialoceles: a prospective study. Brit J Surg. 1985;72:42-44.

6 Smith F. Collective review. flaps utilized in facial and cervical reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1951;7:415-455.

7 New GB, Figi FA. The repair of postoperative defects involving the lips and cheeks secondary to malignant tumors. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1936;62:182-190.

8 Menick FJ. Reconstruction of the cheek. Plast Reconst Surg. 2001;108:496-504.

9 Larrabee WFJr, Sherris DA. Principles of facial reconstruction. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1995.

10 Jackson IT. Local flaps in head and neck reconstruction. St Louis, MO: Quality Medical, 2002.

11 Johnson SC, Bennett RG. Double Z-plasty to enhance rhombic flap mobility. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:128-132.

12 Borges AF. Choosing the correct limberg flap. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 1978;62:542-545.

13 Borges AF. The rhombic flap. Plast Reconst Surg. 1981;67:458-466.

14 Becker FF. Rhomboid flap in facial reconstruction: new concept of tension lines. Arch Otolaryngol. 1979;105:569-573.

15 Cabrera RC, Zide BM. Cheek reconstruction. In: Aston SJ, Beasley RW, Thorne CHM, editors. Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery. fifth edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:501-512.

16 Metzger JT. Joseph Imre and the Imre Flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1959;23:501-509.

17 Jelks GW, Jelks EB. Prevention of ectropion in reconstruction of facial defects. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28:297-302.

18 Guerrerosantos J, Lopez-Luque J. Basal cell carcinoma of the cheek, malar region, and lower eyelid: the role of large cheek-neck flaps. Ann Plast Surg. 1988;20:304-312.

19 Mustarde JD. The use of flaps in the orbital region. Plast Reconst Surg. 1970;45:146-150.

20 de Cholnoky T. The repair of extensive soft tissue losses of the cheek. Plast Reconst Surg. 1955;16:288-291.

21 Cook TA, Israel JM, Wang TD, et al. Cervical rotation flaps for midface resurfacing. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:77-82.

22 Juri J, Juri C. Advancement and rotation of a large cervicofacial flap for cheek repairs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;64:692-696.

23 Patterson HC, Anonson C, Weymuller EA, Webster RC. The cheek–neck rotation flap for closure of temporo-zygomatic cheek wounds. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984;110:388-398.

24 Crow ML, Crow FJ. Resurfacing large cheek defects with rotation flaps from the neck. Plast Reconst Surg. 1976;58:196-200.

25 Stark RB, Kaplan JM. Rotation flaps, neck to cheek. Plast Reconst Surg. 1972;50:230-233.

26 Katz AE, Grande DJ. Cheek–neck advancement-rotation flaps following mohs excision of skin malignancies. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:949-955.

27 Al-Shunnar B, Manson, PN. Cheek reconstruction with laterally based flaps. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28:283-296.

28 Garrett WS, Giblin TR, Hoffman GW. Closure of skin defects of the face and neck by rotation and advancement of cervicopectoral flaps. Plast Reconst Surg. 1966;38:342-346.

29 Kaplan I, Goldwyn RM. The versatility of the laterally based cervicofacial flap for cheek repairs. Plast Reconst Surg. 1978;61:390-393.

30 Kroll SS, Reece GP, Robb G, et al. Deep-plane cervicofacial rotation-advancement flap for reconstruction of large cheek defects. Plastic Reconst Surg. 1994;94:88-93.

31 Kouba DJ, Miller SJ. The J-plasty advancement flap for reconstruction of malar cheek defects. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:78-80.

32 Dingman RO, Derman GH. Lateral cheek and posterior auricular transposition flap. In: Strauch B, Vasconez LO, Hall-Frindlay EJ, editors. Grabb’s encyclopedia of flaps. Boston: Little, Brown; 1990:395-398.

33 Goldminz D, Bennett RG. Cigarette smoking and flaps and full-thickness graft necrosis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;177:1012-1015.

34 Marrero G, Eliezri Y. The use of the SMAS to close Mohs defects invading into the parotid gland. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:1335-1337.