CERVICAL SPINE

SPECIAL TESTS FOR NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Relevant Special Tests

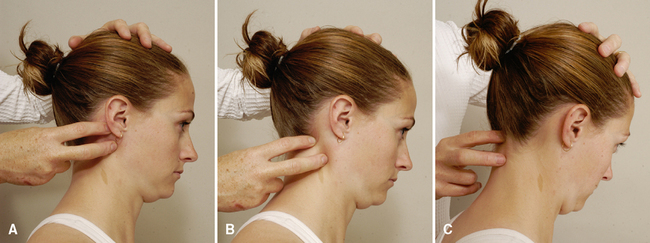

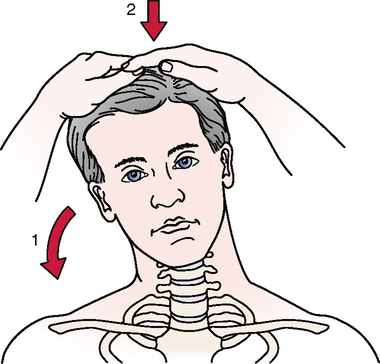

Foraminal compression test (Spurling’s test)

Maximum cervical compression test

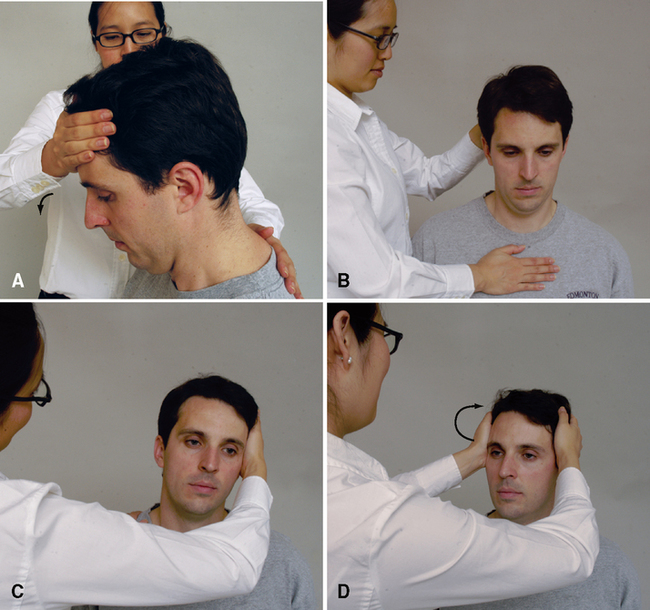

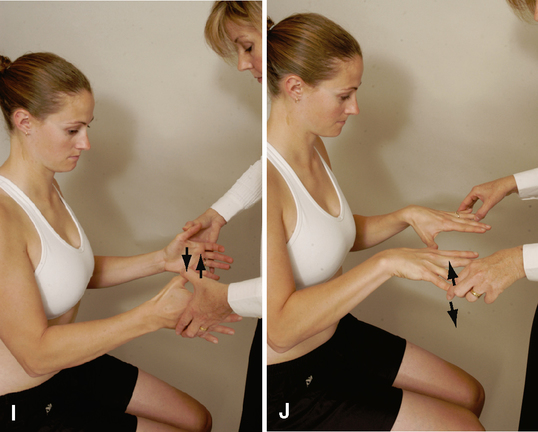

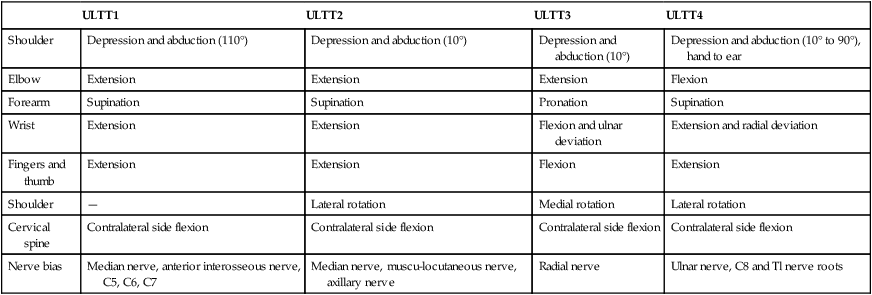

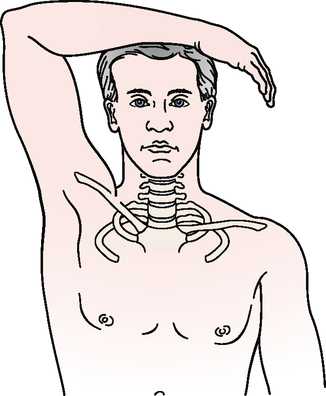

Upper limb tension tests (ULTTs) (brachial plexus tension or Elvey test)

Epidemiology and Demographics

Radicular and neurological symptoms cannot be diagnosed solely on the basis of demographics or epidemiology. The neurological symptoms are a reflection of another pathological condition (that is, the nerve is damaged or irritated, but the source of the damage or irritation is another structure or a part of the injury healing process); therefore, the symptoms take on the demographics of that particular pathological condition. According to a study by Wainner et al.,15 the prevalence of radicular symptoms was 23% in a sample of patients who underwent a standardized electrophysiological examination.

Relevant Signs and Symptoms

A common pattern for this pathological condition may or may not include the following:

• Pain in the neck, intrascapular region, or upper extremity

• Radiation of symptoms into the shoulder, elbow, or distal component of the dorsal and/or palmar aspect of the hand, depending on whether a nerve root (dorsal and palmar) or peripheral nerve (dorsal and/or palmar) is involved

• Pain, tingling, and/or numbness into the shoulder (anterior or posterior) and/or arm

• Aggravation of symptoms by neck movement or different postures

• Symptoms of short or long duration

• A patient over 40 years of age

• Limited ROM as a result of muscle spasm

• Weakness (atrophy may or may not be present, depending on the amount and duration of pressure on the nerve)

• Pain associated with limited ROM of the cervical spine (usually as a result of muscle spasm)

• Sensation changes along the dermatome pattern of the suspected radiculopathy or peripheral nerve lesion

Mechanism of Injury

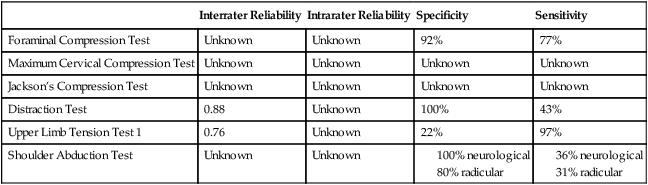

RELIABILITY/SPECIFICITY/SENSITIVITY COMPARISON15–20

| Interrater Reliability | Intrarater Reliability | Specificity | Sensitivity | |

| Foraminal Compression Test | Unknown | Unknown | 92% | 77% |

| Maximum Cervical Compression Test | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| Jackson’s Compression Test | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

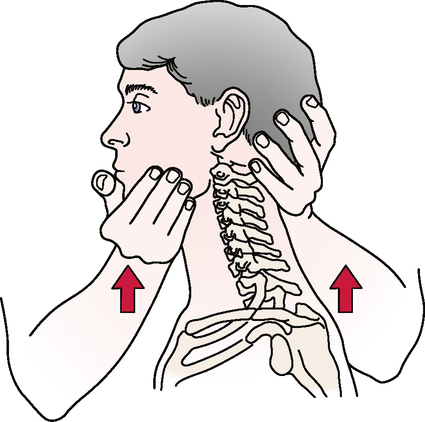

| Distraction Test | 0.88 | Unknown | 100% | 43% |

| Upper Limb Tension Test 1 | 0.76 | Unknown | 22% | 97% |

| Shoulder Abduction Test | Unknown | Unknown |

SPECIAL TEST FOR VASCULAR SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS31–33

Relevant Special Test

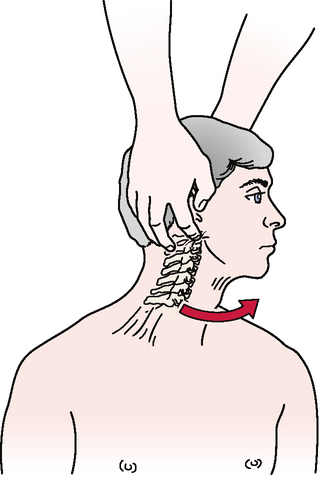

Vertebral artery (cervical quadrant) test

Epidemiology and Demographics

In the United States, 25% of strokes occur in a vertebrobasilar distribution. Age is a factor in that the incidence of vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) increases with age. The incidence is highest in individuals 60 to 70 years old. Men are more prone to VBI then women, and African Americans have a greater prevalence then Caucasians.34–36

Mechanism of Injury

Licht et al.37,38 conducted two studies that addressed the effect of cervical position on blood flow. They found no significant decrease in contralateral blood flow volume despite decreases in blood flow velocity. Yi-Kai et al.39 found that vertebral artery flow decreased with extension and rotation in both the contralateral and ipsilateral vertebral arteries, with the most significant decrease occurring in the contralateral artery.

After an extensive review of studies on vertebral artery blood flow, Terrett40 concluded that rotation with or without extension applies the most stress to the vertebral arteries, with the greatest stress to the vertebral artery occurring between the atlas and axis transverse foramina. Lateral flexion of the neck appeared to have little effect on vertebral artery blood flow.

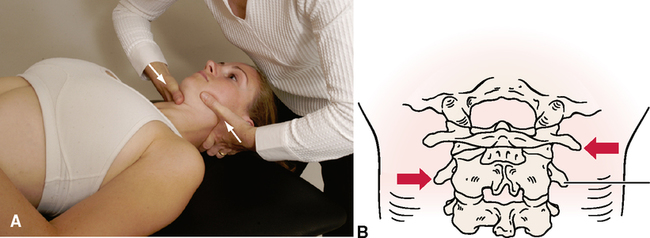

SPECIAL TESTS FOR CERVICAL INSTABILITY

Relevant Special Tests

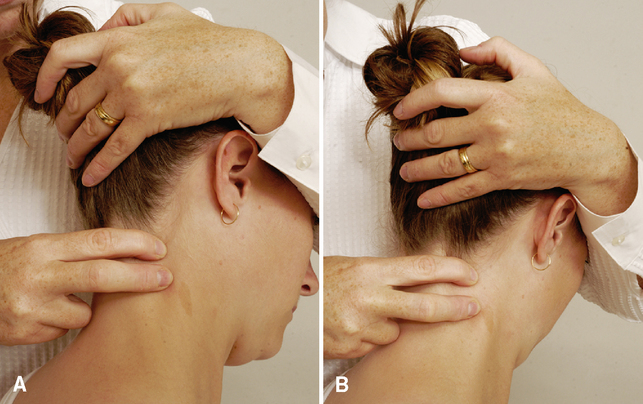

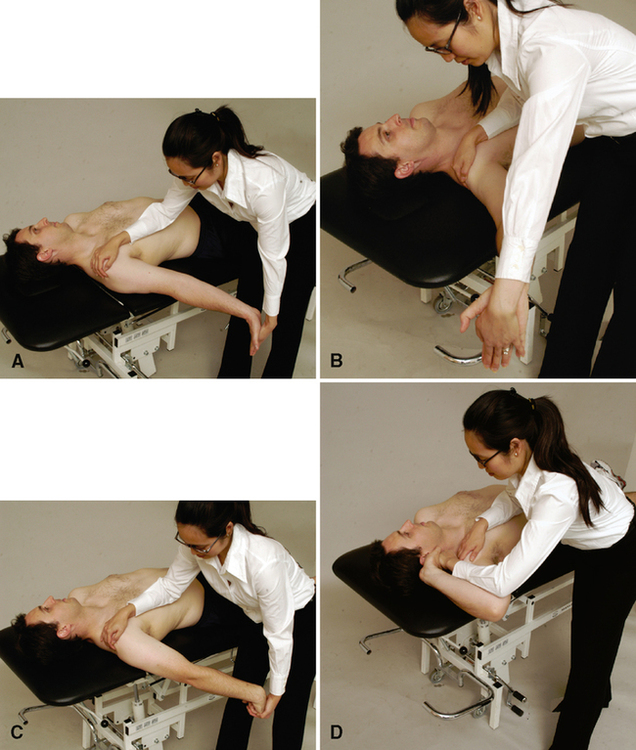

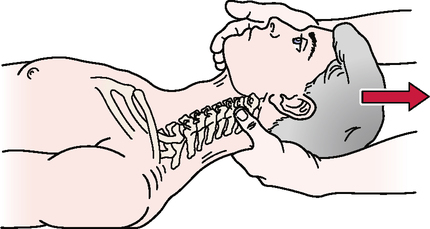

Aspinall’s transverse ligament test

Transverse ligament stress test

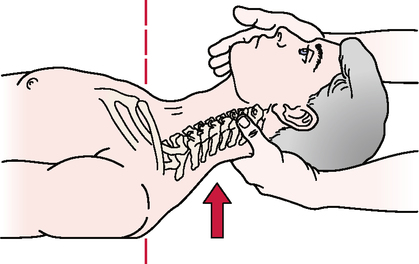

Anterior shear or sagittal stress test

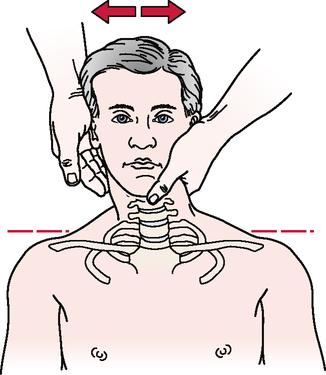

Atlantoaxial lateral (transverse) shear test

Epidemiology and Demographics

In adults, 15% of all fractures of the cervical spine involve the odontoid process; in children under age 7 years, 75% of these fractures involve the odontoid.55–57 Cervical spine subluxations are seen in 43% to 86% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. They occur more frequently in men, even though women have a greater propensity for rheumatoid arthritis. Atlantoaxial subluxation occurs in 11% to 39% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.58–60 Cervical instability should be highly suspected if the patient history includes a complaint of a feeling of instability, a lump in the throat, lip paresthesia, severe headache (especially with movement), muscle spasm, nausea, or vomiting.4

Mechanism of Injury

Common means of injury include motor vehicle accidents and falls that involve head trauma. Biomechanically, if the transverse ligament or odontoid process is damaged, C1 translates forward (subluxes) on C2 during upper cervical flexion. This results in spinal cord or brain stem symptoms as the posterior aspect of C1 encroaches on the spinal cord. Some have hypothesized that odontoid fractures occur as a result of trauma that involves a combination of flexion, extension, and rotation.55,56 Although the mechanism of injury typically is trauma, some disease processes (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, Cushing’s disease, and Down’s syndrome) can weaken the bone and ligaments to the point of failure or increased laxity.

Clinical Note/Caution

• The examiner should use caution when testing for upper cervical instability. Generally, these patients have significant muscle guarding in the upper cervical region, and if spinal segments truly are injured or lax, care must be taken not to injure the involved structures further. Slow, gentle motions should be used for the test.

SPECIAL TEST FOR MUSCLE STRENGTH

Relevant Special Test

Epidemiology and Demographics

Neck pain affects 10% of the population in the United States at any given time. It is more common in women then in men.67 Although the exact number of patients with altered muscle recruitment patterns is not known, it seems logical to hypothesize that many, if not all, individuals with neck pain also have altered muscle strength and endurance in the cervical deep neck flexors.

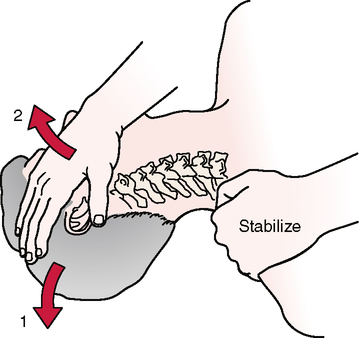

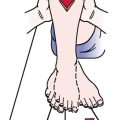

SPECIAL TEST FOR FIRST RIB MOBILITY

Relevant Special Test

Relevant Signs and Symptoms

• Upper thoracic and/or cervicothoracic pain

• Cervical tightness or pain (muscle spasm)

• Symptoms that can be exacerbated by breathing

• Symptoms that radiate into the upper extremity, including numbness, tingling, skin pallor, and changes in skin temperature

• Neurological or vascular symptoms in the upper quarter region (thoracic outlet syndrome/brachial plexus injury)

Mechanism of Injury

The condition may manifest as thoracic outlet syndrome, brachial plexus injury, or limited cervical or shoulder motion. Clinically, first rib dysfunction or first rib mobility limitations are more commonplace. Lindgren71 postulated that the first rib is “susceptible to subluxation because it lacks a superior supporting ligament.” Subluxation of the first rib may be due to the pull of the scalene muscles. If an accessory movement pattern is seen with respiration or if the scalene muscles are guarding injured cervical tissue, the mobility of the first rib may be affected. Fracture of the first rib may result from direct blows to the rib, but actual fractures are rare. This may be due partly to the smaller size of this rib compared with the other ribs and its protected position behind the clavicle. When they occur, fractures of the first rib can cause subsequent trauma to the arteries, veins, and nerves of the upper extremity. First rib dysfunction also may result from automobile accidents, which may cause either compressive or tensile forces on the first rib.