61 Cervical Radiculopathy

Clinical Presentation

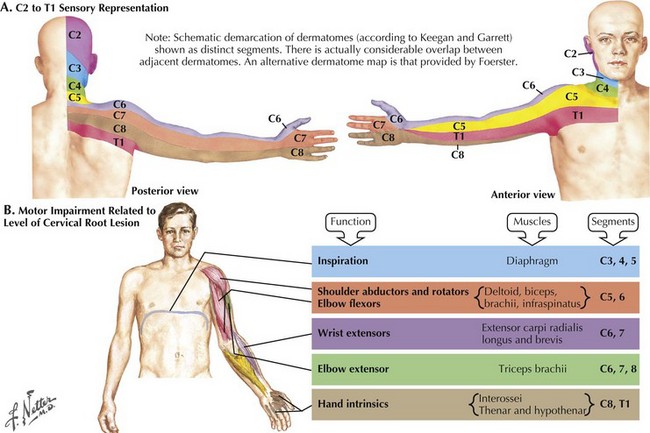

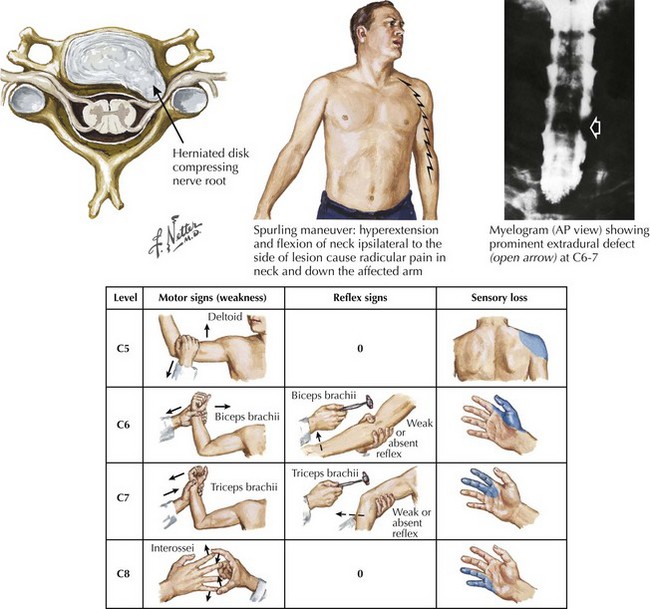

The clinical presentations of cervical radiculopathy depend on the specific root involved. It is unusual to have multiple nerve roots compressed at one time. The usual symptoms are pain, motor weakness, and sensory disturbance. Neck and/or medial scapular pain commonly occur with cervical root compression; shoulder or arm pains are often present. Typical clinical findings include both arm weakness and sensory disturbance appropriate to the affected nerve root (Fig. 61-1). Neck movement often exacerbates the radicular pain and may result in an electric shock–like sensation (Fig. 61-2). Very rarely, pressure on the spinal cord as well as the nerve root may result in concomitant evidence of myelopathy. In any patient with cervical radiculopathy, clinical examination requires careful evaluation for evidence of a myelopathy by making certain the neurologic examination does not demonstrate a spastic gait with enhanced muscle stretch reflexes, a Babinski sign, and evidence of a spinal cord sensory level.

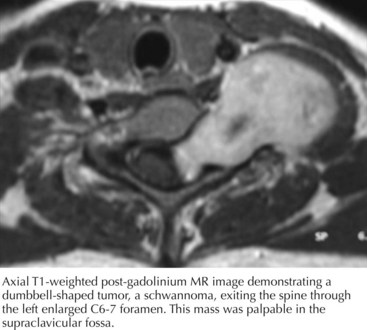

Of the various cervical radiculopathies, C7 nerve root is the most commonly affected. It exits the spinal canal between C6 and C7. Typically, compression leads to pain in the posterior arm. Unlike C5 and C6 lesions, C7 has little functional overlap with other roots. C7 innervates the triceps muscle, which extends the elbow (see Fig. 61-2). Unless patients perform activities that demand extension of the elbow, such as hammering for a carpenter, serving in tennis, rowing, or performing pushups, many individuals with a C7 radiculopathy are unaware of significant triceps weakness. In order to best ascertain the presence of triceps weakness, the examiner must ask the patient to flex the arm at the elbow to 90 degrees and then have the patient try to extend against resistance. In contrast, if one first asks the patient to extend his arm fully, relatively subtle degrees of weakness will be missed. In repose, gravity extends the elbow in most cases. Sensory loss in C7 radiculopathy usually extends to the index and middle fingers (Table 61-1).

C5 is the least frequent level for radiculopathy. The C5 nerve root exits the spine between the C4 and C5 vertebral bodies. Compression of the C5 root produces pain within the medial scapula and into the upper arm; the pain rarely radiates below the elbow. There may be weakness of the deltoid resulting in difficulty carrying out tasks with the arm elevated (see Fig. 61-2). Sensory loss will be over the shoulder and upper arm and is often minimal (see Table 61-1).

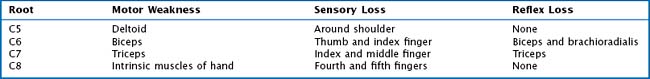

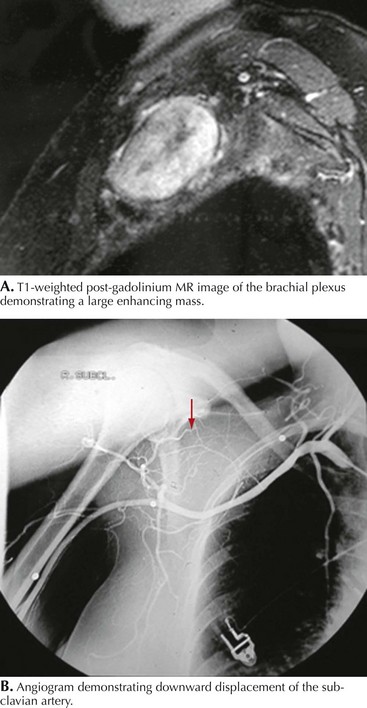

When evaluating a patient with a suspected radiculopathy, it is important to define the temporal profile as well as the degree of progression of the symptoms. Has there been slow progression or rapid worsening? Has there been a plateau or improvement in the condition? How long have the symptoms persisted? The severity and quality of the pain and its provocative factors provide other useful information. In particular, does the arm pain worsen with movement of the neck? Is the pain of an electric quality? It is important to palpate the axilla or supraclavicular fossa, as a mass there could suggest the presence of an extraspinal tumor (Fig. 61-3) or a tumor of the brachial plexus (Fig. 61-4).

Differential Diagnosis

A modest number of pathologic conditions affect the cervical spine and require consideration in the evaluation of the individual with neck pain associated with limb muscle weakness and sensory loss. Radiculopathy secondary to ruptured cervical disc is the most common cause (Fig. 61-5). Degenerative encroachment of the neural foramen from cervical spondylitic disease is another common cause. Primary or secondary neoplastic tumors of the cervical spine or vertebral infection can mimic disc herniation. Metastatic extradural tumor is the most common neoplasm within the cervical spine; the common sites of origin are breast, lung, prostate, and myeloma. The intradural extramedullary tumors, that is, schwannoma and meningioma, are also considerations. In contrast, intramedullary lesions, including a tumor or syrinx, usually present with symptoms of myelopathy. Spinal infection, especially epidural abscess, has increased in frequency; this may be due to sepsis associated with infection in the skin, wounds, urinary tract, and dental manipulation; there is a higher incidence in drug abusers and immune-suppressed patients. Patients with spinal infection usually have a great deal of spine and root pain and may have significant myelopathy. The presence of myelopathic signs, in this clinical setting, demands urgent surgical decompression. Furthermore, these patients frequently have significant spinal instability, which must be a consideration when planning surgery.

Diagnostic Approach

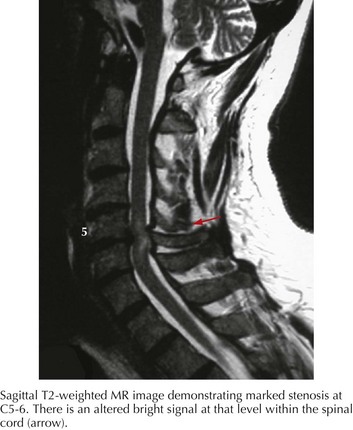

MRI is the imaging modality of choice for evaluating the spine and spinal cord. Occasionally open MRI or CT myelography are good options for claustrophobic patients. Imaging studies will demonstrate the nerve root compression caused by disc herniation or spondylosis. A bright signal in the spinal cord on the T2-weighted image is indicative of an injury to the cord (Fig. 61-6). Additionally, it is possible to visualize tumors within the vertebrae or epidural space. Intradural tumors have a well-defined relationship to both the nerve root and spinal cord; MRI clearly demonstrates these lesions. Extramedullary tumors usually readily enhance with gadolinium; in contrast, intramedullary tumors are often difficult to differentiate from intrinsic spinal cord demyelinating lesions such as multiple sclerosis.

Spinal computed tomography (CT) has limited value when used as a stand-alone diagnostic modality. However, CT used in conjunction with myelography is particularly useful in patients unable to have an MRI (e.g., because of cardiac pacemakers). Standard myelography followed by postmyelogram CT will show nonfilling of nerve root sleeves or direct compression of the nerve roots (see Fig. 61-2). It may also demonstrate pressure on the spinal cord (extramedullary lesions) as well as pathology within the cord (intramedullary lesions). CT is particularly effective for demonstration of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). Additionally reconstructed spinal CT is an excellent study when attempting to understand complex spinal deformities. We recommend electrodiagnostic studies if there is conflict between the clinical story and imaging findings or if a diagnosis other than radiculopathy is suspected, for example, brachial plexopathy.

Albert TJ, Murrell SE. Surgical management of cervical radiculopathy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999 Nov-Dec;7(6):368-376.

Freidberg SR, Pfeifer BA, Dempsey PK, et al. Intraoperative computerized tomography scanning to assess the adequacy of decompression in anterior cervical spine surgery. J Neurosurg (Spine 1). 2001;94:8-11.

Guzman J, Haldeman S, Carroll LJ, et al. Clinical practice implications of the bone and joint Decade 2000-2010. Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: from concepts and findings to recommendations. Spine. 2008 Feb 15;33(Suppl. 4):S199-213. Review

Levine MJ, Albert TJ, Smith MD. Cervical radiculopathy: diagnosis and nonoperative management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996 Nov;4(6):305-316.

Wirth FP, Dowd GC, Sanders HF, et al. Cervical discectomy. A prospective analysis of three operative techniques. Surg Neurol. 2000 Apr;53(4):340-346.