Chapter 46 Cervical Laminoplasty

General Principles and History

Laminectomy was first introduced to release the spinal cord compressed at multiple levels, although it fell into relative disfavor due to complications such as laminectomy membrane, segmental instability, kyphosis, and late neurologic deterioration. Ventral decompression and fusion or posterior fusion in addition to laminectomy was a solution in the United States and European countries, whereas laminoplasty was created in Japan, especially for treating ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). Such ossification is difficult to remove directly via a ventral approach because the extremely hard ossification often tightly adheres to the dura mater. Direct resection of the ossification, therefore, was strongly associated with the potential risk of disastrous cord damage, and postoperative displacement of the grafted bone or pseudarthrosis was not rare, because a long bone graft was needed to span the trough after resection of the long OPLL. All of these complications kept most surgeons away from employing ventral surgery for cervical OPLL. Laminoplasty was developed as a safer and more reliable procedure to treat OPLL in 1971 by Hattori et al.,1 who expected to enlarge the spinal canal and to relieve neural compression while maintaining a skeletal and ligamentous dorsal arch to prevent epidural scarring and malalignment of the cervical spine. Although this procedure, the so-called Z-shaped laminoplasty, was rather complicated, simpler and more feasible laminoplasty procedures were devised and are now divided into two categories: unilateral (hinge) laminoplasty and bilateral (hinge) laminoplasty. Given that the patients with compressive myelopathy generally have a developmentally narrow spinal canal, decompression over the entire cervical spine with laminoplasty seems more reasonable than ventral decompression surgery, in which operated levels are restricted and adjacent segment disease can take place several years later. Thus, the number of patients with compressive myelopathy who undergo laminoplasty is increasing each year. Several trials to eliminate the disadvantages of laminoplasty are discussed herein.

Contraindications

A cervical kyphosis of greater than 5 to 10 degrees is considered a contraindication for laminoplasty, because the spinal cord cannot be released from the anterior lesion if the dorsal space is made by laminoplasty.

Subaxial lesions in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have been treated with arthrodesis, although reduction of neck motion, swallowing disturbance, and adjacent segment disease are not rare after spinal fusion. Laminoplasty is an alternative to diminish the drawbacks associated with arthrodesis. Retrospective investigation in our series revealed that patients with nonmutilating-type RA can benefit from laminoplasty if subaxial subluxation is mild.2 In contrast, mutilating-type RA and/or RA with vertebral slippage more than 5 mm is a contraindication for laminoplasty. Cervical myelopathy associated with athetoid cerebral palsy may be best treated with laminoplasty combined with fusion. A screw-rod system or a long bone graft spanning all fused levels with a postoperative halo vest is a common technique to attain spinal fusion. Laminoplasty alone has little effect on the myelopathy of athetoid cerebral palsy. Patients undergoing hemodialysis may be candidates for laminoplasty, unless they have destructive spondyloarthropathy, in which spinal instability should be managed by spinal fusion. Pyoderma on the nape skin is a contraindication for laminoplasty, because of the high risk for surgical site infection. Pyoderma is an infectious dermal disease well observed on buttock skin, although head and neck regions may also be affected.

Techniques

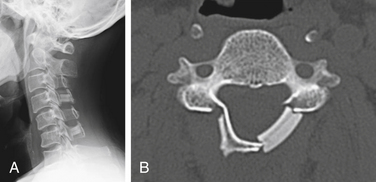

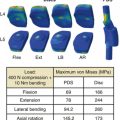

Various types of laminoplasty are in clinical use. They are divided into two major categories: unilateral (hinge) laminoplasty and bilateral (hinge) laminoplasty. In unilateral laminoplasty, or open-door procedure, two bony gutters are drilled on either side of the lamina-facet junction. The gutter on one side is cut out and the lamina is opened by elevating this edge, while the gutter on the other side functions as a hinge by following gentle fracture. The side to be opened does not depend on the laterality of compression. A left-side opening is generally convenient for right-handed surgeons. The opened lamina is kept in situ by sutures placed between holes drilled in the lamina and the facet joint capsule. Postoperative reclosure of the lamina, however, can take place, and the opening space may be spanned by a spacer to maintain the enlarged spinal canal. Resected spinous processes or ceramic spacers are often inserted at every two laminae and fixed by sutures between the lamina edge and the lateral mass. The nonfixed laminae are also kept open by a yellow ligament attached to the adjacent fixed laminae (Fig. 46-1). Small metal plates are alternative implants to maintain the opened lamina, although they are not as popular in Japan as in Western countries. Metal plating adds to the complexity of the operation, is time-consuming, and adds to the expense.

During the introduction period of laminoplasty in Japan, a cervical collar was generally applied for a few months after surgery. Surgeons thought that external support was a prerequisite to facilitate bony union of the hinged gutters or grafted bones. However, as unfavorable spine fusion and aggravation of axial neck pain were recognized as the adverse effects of collar application, many surgeons discontinued this practice. In contrast, patients are encouraged to perform isotonic muscle exercises in the early postoperative period to prevent muscle weakness.

Modifications of the Procedure

Reattachment of the Nuchal Muscles to the Spinous Process of the Axis

The rectus major, inferior oblique, and semispinalis cervicis muscles attached to the axis are considered to lend mechanical stability to the cervical spine. These muscles are, therefore, best preserved with laminoplasty, although they often disturb access to the C3 lamina by covering it. Formerly, we cut the tips of the spinous process of the axis along with the origin of these muscles. After opening all laminae, the bony fragments to the axis are replaced, so that these muscles can exert traction force again after laminoplasty.3 Aggressive retraction, but not cutting, of these muscles is an alternative way, and some surgeons recommend C3 laminectomy to preserve the muscles attached to the axis.

Outcomes

Long-term outcomes of laminoplasty are also excellent and maintained for 5 years from surgery, after which neurologic gain is gradually lost in some patients. Approximately 30% of the patients who underwent laminoplasty were reported to encounter neurologic deterioration in the 10-year follow-up.4 Late deterioration is more frequent in cases of OPLL (27–30%) than in cases of spondylosis (16–30%).4 Neurologic deterioration after laminoplasty can be attributed to osteoarthritis of the hip or knee joints, degenerative lumbar diseases, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, minor trauma, age-related dysfunction, progression of cervical OPLL, and thoracic spine ossification, although no causative factors can be identified in some patients. Increase in OPLL thickness is as frequent as 70% of cases in the 10-year follow-up after laminoplasty, although neurologic deterioration results in only 3% to 7%.5 Thus, the long-term outcome of laminoplasty can be concluded to surpass that of anterior surgery, which definitely has adjacent segment diseases.

Complications

Perioperative Complications

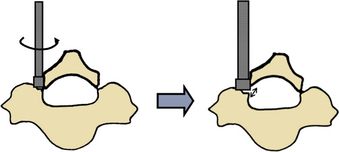

Epidural bleeding is a common complication of spinal surgery. The typical blood loss for laminoplasty is about 100 to 500 mL. The epidural venous plexus is rich in the lateral part of the spinal canal, but it is sparse in the midline. In unilateral laminoplasty, bony gutters are made just on the rich epidural vein and bleeding can be massive. Surgeons should take care not to perforate the inner cortex of the lamina, especially when using a steel bur. The best way to cut off the lamina on the opened side is to crack the evenly thinned lamina by rotating the elevator inserted in the gutter (Fig. 46-2). Even after every lamina is cut off in this way, massive bleeding can occur during lamina opening. If a suction tube is effective to allow visualization of the dural surface, lamina opening should be continued to the last lamina prepared because dural expansion by lamina opening often squeezes dilated veins. If bleeding is overwhelming and far beyond suction capacity, the opening process should be transiently interrupted and surgeons may have to wait for a few minutes after placing hemostatic collagen onto the vein until the blood flow decreases. Huge vein networks are difficult to cauterize using a bipolar coagulator. Bleeding, however, is minimal in most cases of unilateral laminoplasty.

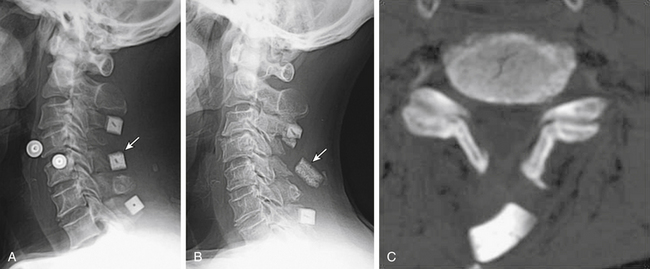

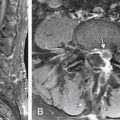

Epidural hematoma formation is another common complication of spinal surgery. A subfascial closed wound drain tube should be placed to prevent hematoma formation, although the tube placed on laminae often has no effect in evacuating blood collection under laminae (Fig. 46-3). Laminoplasty has an advantage in that an opened lamina functions as a protector against posterior muscles that may compress the spinal cord, whereas with laminectomy, the exposed spinal cord is susceptible to compression by hematoma or muscles.

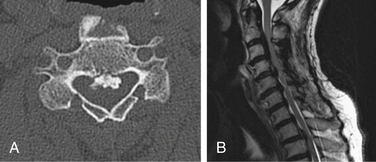

Postoperative displacement of an implanted ceramic spacer is more often observed after bilateral laminoplasty than after unilateral laminoplasty (Fig. 46-4). Although ceramic spacers usually migrate dorsally, they can cause not only dural laceration but also cord injury if they displace ventrally.6 Lamina dropping, or falling forward, on the hinged side is one of the most common complications of laminoplasty. When surgeons realize the complete separation of the hinged side cortex, they should remove the floating lamina to avoid neural injury. Making the bony hinge appropriately flexible is a critical point of laminoplasty, because too loose a hinge makes the lamina drop and too rigid a hinge results in reclosure of the opened lamina (Fig. 46-5).

Palsy of C5 has been the biggest topic of debate in cervical spine surgery. Scoville7 and Stoops8 described this complication after laminectomy in 1961, but it was first reported after laminoplasty in 1986. Postoperative C5 palsy is defined as paresis of the deltoid muscle and/or the biceps brachii muscle after cervical decompression surgery without any deterioration of myelopathy symptoms. The vast majority of C5 palsies occur within a week following surgery, and recent studies reveal a shorter latency between surgery and the onset of the C5 palsy than had been previously considered. Some patients present with palsy on the day of surgery. Although the reason why the palsy occurs exclusively in the unilateral C5 nerve root has been extensively discussed, recent papers reveal that the palsy occurs in every root, including C5, C6, C7, and C8, individually or in combination.9,10 The incidence of palsy is 5% for only the C5 root but 10% for all roots. The incidence of palsy is similar between laminoplasty and anterior cervical surgery. C5 palsy generally recovers spontaneously as long as the palsy is mild. Most mild palsy with a manual muscle testing (MMT) grade of 3 or 4 fully recovers within 6 months, whereas severe palsy with an MMT grade 2 or less recovers only up to a useful level, often taking more than 6 months.

The cause for C5 palsy or upper limb palsy in a broader sense still remains unknown. Inadvertent injury to the nerve root during surgery, nerve root traction caused by consecutive dorsal shifting of the cord following decompression surgery (“tethering phenomenon”), spinal cord ischemia due to decreased blood supply from radicular arteries, segmental spinal cord disorder, and reperfusion injury of the spinal cord have been proposed so far, although none of these alone can effectively account for all of the clinical characteristics of C5 palsy. Tethering phenomenon has been considered the most likely pathogenesis of C5 palsy for a long time. Some authors, however, report that C5 palsy does not necessarily emerge in patients whose dorsal migration of the spinal cord is excessive after laminoplasty.11,12 Spontaneous recovery of C5 palsy or the palsy after anterior surgery cannot be accounted for by this tethering theory. Reperfusion injury has been advocated recently as a possible cause of C5 palsy. A chronically compressed spinal cord may be injured by free radicals after being exposed to rapid reperfusion of the blood flow. However, the distribution of palsy restricted to a single segment is difficult to explain by reperfusion of the spinal cord. The most recent hypothesis for C5 palsy is thermal damage to the nerve roots. The experimental data suggest that tissues adjacent to drilled bone, especially nerve roots, can be damaged by friction heat from a high-speed drill, which is often beyond 100°C without water irrigation.13 In experiments simulating hyperthermia therapy, not only the latent period between thermal damage and palsy but also motor recovery after several weeks is indicated. This characteristic coincides with the clinical course of C5 palsy.

Axial neck pain is the most frequent complication of laminoplasty, with an incidence of 10% to 20%. It can be defined as the appearance of neck and shoulder pain after cervical spine surgery. Since its first report in 1992, many attempts were made to reduce this notorious complication. The most effective preventive measure is to discard the cervical collar after surgery. Long-term collar application definitely aggravates axial pain, and no collar application decreases the incidence and intensity of axial pain. A trend of not using a collar after laminoplasty has emerged. The pathogenesis of axial pain, however, is still obscure. Because axial pain is much more frequently observed after laminoplasty than after anterior surgery, the disruption of posterior neck tissues is suspected to be the origin of pain. Intermittent decompression by skip laminectomy14 or minimally invasive laminoplasty using a tubular retractor seems promising to decrease axial neck pain by preserving posterior neck tissues. Such procedures, however, appear complicated and time-consuming. We realized that postoperative axial pain significantly decreased by limiting the range of laminoplasty from C3-7 to C3-6.15 The C7 spinous process with various tissue attachments has a critical biomechanical importance and should be spared from the range of laminoplasty. Given the rarity of cord compression at C6-7 in cervical spondylosis, C3-6 laminoplasty seems to be a necessary and sufficient procedure, although another strategy may be needed in treating OPLL.

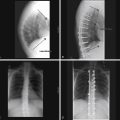

Late Complications

Long-term outcome of laminoplasty is generally good, and late neurologic complications such as adjacent segment disease are seldom reported so far. Late complications are largely radiologic changes, which are divided into alignment change, range of motion change, and instability development including slippage. Sagittal alignment tends to be kyphotic after laminoplasty, although one of the advantages of laminoplasty is the paucity of postoperative kyphosis compared with conventional laminectomy. Lordotic alignment accounts for 70% of patients before laminoplasty and 50% after laminoplasty in both patients with spondylosis and OPLL. However, severe kyphosis resulting in neurologic deterioration seldom develops. Range of cervical motion significantly decreases to 20% to 35% of the preoperative range 10 years after laminoplasty. The reduction in range of motion is greater after laminoplasty than after anterior corpectomy surgery that fuses 2.5 interspaces on average. Although the unintended fusion of facet joints or of opened laminae is supposed to cause the reduction in range of motion, no application of a cervical collar and early postoperative neck exercise can be expected to minimize the reduction in range of motion. Segmental instability, vertebral slippage, and adjacent segmental degeneration that requires treatment are rare after laminoplasty.

Chiba K., Ogawa Y., Ishii K., et al. Long-term results of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy: average 14-year follow-up study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2998-3005.

Hosono N., Miwa T., Mukai Y., et al. Potential risk of thermal damage to nerve roots by a high-speed drill: a possible cause of C5 palsy after cervical spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2009;11:1541-1544.

Hosono N., Sakaura H., Mukai Y., et al. C3-6 laminoplasty takes over C3-7 laminoplasty with significantly lower incidence of axial neck pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1375-1379.

Iwasaki M., Kawaguchi Y., Kimura T., et al. Long-term results of expansive laminoplasty for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine: more than 10 years follow up. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(2 Suppl):180-189.

Kaito T., Hosono N., Makino T., et al. Postoperative displacement of hydroxyapatite spacers implanted during double-door laminoplasty. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;10:551-556.

Shiraishi T. A new technique for exposure of the cervical spine laminae. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(Suppl 1):122-126.

Yonenobu K., Wada E., Ono K. Laminoplasty for myelopathy. Indications, results, outcome and complications. In: Clark C.R., et al, editors. The cervical spine. ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:1057-1071.

1. Kawai S., Sunago K., Doi K., et al. Cervical laminoplasty (Hattori’s method). Procedure and follow-up results. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988;13:1245-1250.

2. Mukai Y., Hosono N., Sakaura H., et al. Laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy caused by subaxial lesions in rheumatoid arthritis. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(Suppl 1):7-12.

3. Yonenobu K., Wada E., Ono K. Laminoplasty for myelopathy. Indications, results, outcome and complications. In: Clark C.R., editor. The cervical spine. ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:1057-1071.

4. Chiba K., Ogawa Y., Ishii K., et al. Long-term results of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy: average 14-year follow-up study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2998-3005.

5. Iwasaki M., Kawaguchi Y., Kimura T., Yonenobu K. Long-term results of expansive laminoplasty for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine: more than 10 years follow up. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(Suppl 2):180-189.

6. Kaito T., Hosono N., Makino T., et al. Postoperative displacement of hydroxyapatite spacers implanted during double-door laminoplasty. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;10:551-556.

7. Scoville W.B. Cervical spondylosis treated by bilateral facetectomy and laminectomy. J Neurosurg. 1961;18:423-428.

8. Stoops W.L. Neural complication of cervical spondylosis; their response to laminectomy and foraminotomy. J Neurosurg. 1961;19:986-999.

9. Sakaura H., Hosono N., Mukai Y., et al. Segmental motor paralysis after cervical laminoplasty. A prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2684-2688.

10. Hasegawa K., Homma T., Chiba Y., et al. Upper extremity palsy following cervical decompression surgery results from a transient spinal cord lesion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:E197-E202.

11. Kurosa Y., Yamaura I., Nakai O. Pathophysiology of postoperative C5 nerve root palsy [in Japanese]. Spine and Spinal Cord. 1993;6:107-114.

12. Sodeyama T., Goto S., Mochizuki M., et al. Effect of decompression enlargement laminoplasty for posterior shifting of the spinal cord. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:1527-1531.

13. Hosono N., Miwa T., Mukai Y., et al. Potential risk of thermal damage to nerve roots by a high-speed drill—a possible cause of C5 palsy after cervical spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2009;91:1541-1544.

14. Shiraishi T. A new technique for exposure of the cervical spine laminae. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(Suppl 1):122-126.

15. Hosono N., Sakaura H., Mukai Y., et al. C3-6 laminoplasty takes over C3-7 laminoplasty with significantly lower incidence of axial neck pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1375-1379.