Cerebrovascular Disorders

Stroke is defined as a neurologic deficit persisting for more than 24 hours. Stroke may be caused by either cerebral ischemia or intracranial hemorrhage. The estimated annual incidence of stroke in children ranges from 2 to 13 per 100,000 person years and is among the top 10 causes of death in childhood.1

The presentation of stroke in children is sometimes heralded by the abrupt onset of a focal neurologic deficit, but often, especially in infants and young children, the symptoms are nonspecific and the diagnosis of stroke is frequently delayed. Although many children who have had a stroke recover completely, more than 75% will have a perceptible persistent neurologic deficit, and more than 40% will have major neurologic sequelae.2

Unlike adults, in whom hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and hypercholesterolemia are frequently identified as risk factors for the development of stroke, cerebrovascular arteriopathy, vascular anomalies, aneurysms, congenital heart disease, sickle cell disease, and hematologic abnormalities are among the most common predisposing conditions in children.1 More than half of all strokes in children are ischemic, caused either by an intrinsic vasculopathy or emboli from a remote source.2 Vascular malformations, aneurysms, and venous sinus thrombosis are the most common causes of hemorrhagic stroke. This chapter focuses on intrinsic vascular abnormalities as causes of ischemic and hemorrhagic pediatric stroke.

Arteriopathy

Ischemic stroke in children has an annual incidence of between 2 and 3 per 100,000 children in the United States.3 The causes of ischemic stroke in children are diverse and include a variety of cerebrovascular entities in approximately 70% of children, such as arterial dissection, moyamoya disease or syndrome, sickle cell disease, isolated angiitis of the central nervous system or vasculitis, coagulopathy, or other known source; the remainder of cases are idiopathic in origin. More than one risk factor may be present. Twenty-five percent of children with ischemic stroke have coexistent cardiac disease.2 Metabolic disorders, such as mitochondrial diseases and hyperhomocysteinemia, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of ischemic stroke in children, especially if the distribution of the infarction does not conform to an arterial territory.

The most common symptoms of ischemic stroke in children are hemiplegia, seizures, fever, dysphagia, headache, and altered level of consciousness. Headache and seizures are especially common in chronic ischemic conditions such as moyamoya disease.4

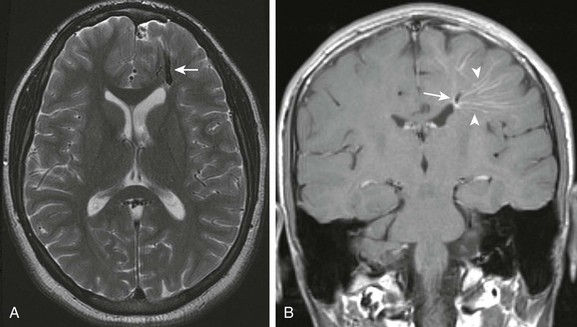

Imaging: The imaging features of ischemic stroke in children are variable and depend on the underlying cause. In acute arterial dissection, an end arterial distribution infarction is often present on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). By contrast, in proximal, chronic steno-occlusive disease such as moyamoya disease (Fig. 36-1), infarctions may be absent, conform to an arterial territory, or lie within the border zones between the major vascular territories. In chronic multivessel steno-occlusive disease, there may be a shift in the location of the vascular border zones because of differential involvement of the various branches of the circle of Willis.

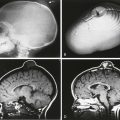

Figure 36-1 A  -year-old child presenting with new-onset right-sided hemiplegia and imaging findings of moyamoya disease.

-year-old child presenting with new-onset right-sided hemiplegia and imaging findings of moyamoya disease.

A, Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery magnetic resonance imaging scan shows a subacute infarct involving the left middle cerebral artery–posterior cerebral artery watershed territory (asterisk). There is periventricular white matter T2 prolongation due to chronic ischemic change (arrowheads). Linear sulcal signal abnormality is demonstrated bilaterally, consistent with slow flow (arrows) in leptomeningeal vessels. B, Frontal projection from digital subtraction angiogram shows severe steno-occlusive changes involving the distal right internal carotid artery (arrow), with occlusion of the middle and anterior cerebral arteries and multiple basal collaterals. C, Lateral projection again shows the distal tapering and occlusion of the supraclinoid internal carotid artery (arrow), multiple basal collaterals, and anterior shift of the posterior cerebral territory through pial collaterals to supply the posterior portions of the middle and anterior cerebral territories.

Noninvasive vascular imaging such as computed tomographic angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) typically shows an abrupt vascular cutoff with dissection and thromboembolic stroke. In moyamoya disease, stenosis or occlusion of the supraclinoid segment of the internal carotid and proximal middle or anterior cerebral artery is usually present, with numerous collateral vessels in the basal ganglia at certain stages of the disorder.5 Vasculitis causes irregular narrowing of medium or small vessels and is inconsistently demonstrated on CTA or MRA.6 Catheter angiography remains the gold standard for the imaging diagnosis of cerebrovascular disease in children and should be considered whenever a small vessel vasculitis is suspected or when surgical treatment is contemplated.

Vascular Anomalies

Vascular anomalies are disorders of vascular development. Although congenital, they may only become symptomatic many months or years after birth. Intracranial vascular malformations are classified according to the vascular channels involved and the hemodynamics of the lesion (high-flow vs. low-flow).7

High-Flow Vascular Anomalies

High-flow vascular anomalies occur when there is an abnormal connection between an artery and a vein that bypasses the normal arteriolar-capillary network. In arteriovenous fistula (AVF), the supplying artery communicates directly with the draining vein through a macroscopic fistula. In arteriovenous malformation (AVM), the supplying artery connects with the draining vein through a plexiform network of abnormal vessels, termed the nidus. Both AVF and AVM are further subdivided, on the basis of anatomic location, into dural, subarachnoid (vein of Galen malformation), pial, or parenchymal (Figs. 36-2, 36-3, and 36-5; e-Fig. 36-4).7,8

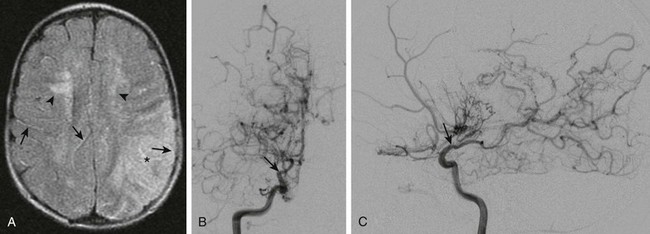

Figure 36-2 Five-month-old girl presenting with vomiting, lethargy, macrocephaly, and scalp vein distension with pulsating veins from dural arteriovenous fistula.

A, Axial T2-weighted image shows an enlarged, partially thrombosed superior sagittal sinus (V). Also noted are prominent middle meningeal arterial branches along the dural surface bilaterally. B, Maximum intensity projection reconstruction of the two-dimensional coronal magnetic resonance imaging venogram shows bilaterally enlarged middle meningeal arteries with fistulae (arrows) to the dilated, partially thrombosed superior sagittal sinus. C, Digital subtraction angiogram—lateral projection demonstrates the dural arteriovenous fistulae with the markedly enlarged middle meningeal artery branches directly communicating through several fistulae (arrows) with the superior sagittal sinus near the torcular herophili.

Figure 36-3 A 12-month-old child presenting with macrocephaly and developmental delay. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a vein of Galen malformation.

A, Axial T2-weighted image shows a dilated median vein of the prosencephalon (V). The straight sinus and torcular herophili are enlarged. Multiple small serpinginous signal voids are present medially between the thalami from enlarged branches from a primitive arterial arcade. Hydrocephalus is present from venous hypertension. B, Sagittal maximum intensity projection from an MRI angiogram confirms a high-flow arteriovenous connection with marked flow related enhancement in the varix and draining sinuses. C, Digital subtraction angiogram—lateral view of the left vertebral artery injection shows enlarged left vertebral, basilar, and posterior cerebral arteries supplying a primitive arterial arcade with a vascular nidus of abnormal vessels draining into the enlarged prosencephalic vein. D, Lateral view of the right internal carotid artery injection demonstrates additional anterior circulation supply to the malformation (arrow).

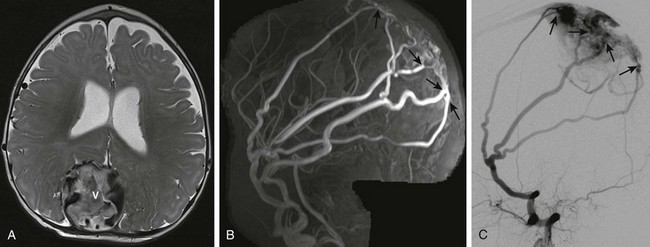

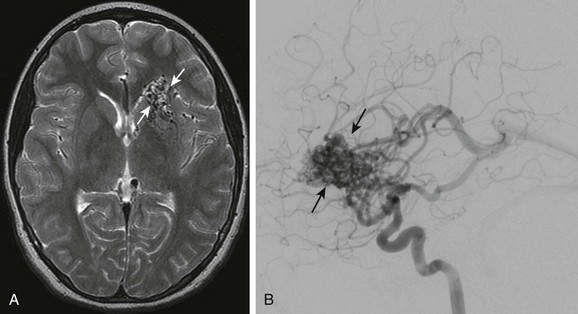

Figure 36-5 An 11-year-old girl presenting with severe headache, vomiting, and left leg weakness is found to have intraventricular hemorrhage and left frontal arteriovenous malformation.

A, Axial T2-weighted image shows multiple signal voids in the left inferior frontal lobe involving the caudate head and basal ganglia. B, Lateral projection of a cerebral angiogram demonstrates the large vascular nidus (arrows) with early opacification of the internal cerebral veins and straight sinus.

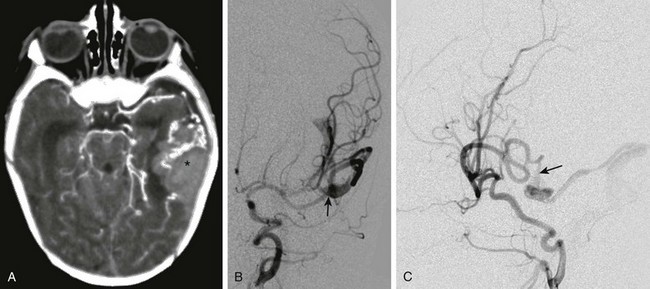

e-Figure 36-4 An 18-day-old child presenting with irritability, poor feeding, and vomiting is found to have a large left temporal hemorrhage on ultrasound.

A, Computed tomography with intravenous contrast shows hemorrhage (asterisk) in the left temporal lobe associated with enlarged vessels. B, Digital subtraction angiogram—frontal projection shows a pial arteriovenous fistula (arrow) supplied by the left middle cerebral artery. C, The lateral projection from the angiogram demonstrates a fistula (arrow) between the middle cerebral artery and the dilated cortical vein.

High-flow vascular malformations may produce symptoms and signs in several ways.7,9,10 The presence of an abnormal connection between a supplying artery and a draining vein allows for potentially rapid blood flow through the anomaly. In the absence of venous outflow obstruction, the malformation may cause high-output cardiac failure due to the lack of regulation of blood flow through the normal arteriolar and capillary network. The lower resistance through the malformation may result in diversion of blood away from the normal brain parenchyma (“steal” phenomenon), producing cerebral ischemia. High-flow malformations also expose the draining veins to arterial pressure, which may cause progressive stenosis of the vein, termed high-flow venopathy. High-flow venopathy may be a cause of seizures or cerebral atrophy due to impaired tissue perfusion from a diminished arterial-venous pressure gradient. Hydrocephalus can develop from increased venous pressures, that result in impaired resorption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (see Fig. 36-3, A). Elevated venous pressure can also result in the development of a varix that predisposes to hemorrhage.

Dural High-Flow Anomalies

Dural AVF or AVM comprise a meningeal arterial supply with dural venous sinus drainage and often present in the prenatal or immediate postnatal period as a cause of fetal or neonatal heart failure (see Fig. 36-2).7,10,11 The anomalies may include a single or multihole fistula or complex malformation. The abnormal connections are frequently located either in the vicinity or in the torcular herophili or involve dural venous sinuses that drain into the torcular herophili.

Vein of Galen Malformations

Vein of Galen malformations (VOGMs) consist of AVF or AVM deriving arterial supply from a primitive choroidal arcade and venous drainage through an aneurysmally dilated median vein of the prosencephalon, the embryologic precursor to the vein of Galen (see Fig. 36-3).7,11,12 The symptoms, signs, and age at presentation associated with VOGMs depend on the angioarchitecture of the anomaly and the degree of venous outflow obstruction. VOGMs with numerous connections between the supplying arteries and the draining vein and without venous outflow obstruction typically produce congestive heart failure in the fetus or neonate due to the shunting of blood through the malformation. Chronic ischemic brain injury occurs from poor brain perfusion caused by arterial steal. Intracranial hemorrhage can occur from rupture of the varix. VOGMs with fewer arteriovenous connections often present later in infancy or childhood with hydrocephalus or brain atrophy caused by progressive stenosis of venous outflow and impaired parenchymal perfusion caused by a decreased arteriovenous pressure gradient (see Fig. 36-3).

Pial High-Flow Anomalies

Pial AVF and AVM comprise a pial arterial supply with cortical venous drainage (see e-Fig. 36-4).7 Pial AVFs or AVMs are rarely detected in the neonate and usually come to medical attention in late infancy or early childhood. The fistulous connections occur along the surface of the brain, resulting in marked dilation of the unsupported superficial cortical draining veins. The anomalies may consist of only a single-hole fistula or may be mixed AVF and AVM. Pial AVF or AVM may be asymptomatic for long periods, being discovered only incidentally on imaging performed for other reasons, or the high-flow anomaly may be a cause of catastrophic intracranial hemorrhage.

Parenchymal High-Flow Anomalies

Intraparenchymal AVMs, like pial anomalies, derive their arterial supply from either the anterior or posterior cerebral circulation (see Fig. 36-5). Parenchymal AVMs usually present after infancy, most often as a cause of intracranial hemorrhage.7,9,10 The angioarchitecture of these anomalies is often less complex than that of similar malformations in adults, although extensive lobar malformations are occasionally encountered. Intranidal aneurysms and varices occur commonly; however, aneurysmal dilation of the supplying arteries is much less frequent than in adults.

Imaging: Imaging in high-flow vascular malformations is directed toward delineation of the vascular anomaly and demonstration of complications. Dural and VOGM AVFs or AVMs may be diagnosed in utero on either obstetrical sonography or fetal MRI.7,8,11 Fetal ultrasound or MRI of dural AVF or AVM shows an off-midline vascular mass with enlarged meningeal arteries. Fetal ultrasound or MRI of VOGM demonstrates a midline vascular mass, with obvious increased flow in the supplying arteries and draining veins on color Doppler examination. In dural AVF or AVM as well as VOGM, fetal cardiomegaly and congestive heart failure with hydrops may be present. In addition to showing the vascular mass, fetal and postnatal MRI scans may show T1 shortening in the white matter, indicating chronic ischemic brain injury. Postnatal CT is now used less frequently to evaluate high-flow anomalies in the neonate but may show chronic ischemic brain injury with loss of gray/white matter contrast and parenchymal calcification, in addition to the vascular anomaly.

Treatment of dural malformations and VOGMs is typically performed via an endovascular approach.9,10,13 Successful treatment of the anomaly requires occlusion of the arteriovenous connection. AVFs may be treated by placement of coils across the lesion, whereas closure of AVMs requires obliteration of the nidus and is best accomplished by using a liquid embolic agent.10,13 Pial and parenchymal malformations are often treated with endovascular embolization, surgical resection, or combined preoperative embolization, followed by surgical resection.9,10,13 Malformations that are not surgically accessible may be treated by using endovascular techniques or focused radiation therapy, including proton beam treatment.14,15

Capillary Telangiectasia

Capillary telangiectasias are composed of dilated capillaries and are found most frequently within the pontine tegmentum (e-Fig. 36-6).16–18 Capillary telangiectasias are usually clinically silent and are noted incidentally on imaging performed for other reasons. Rare cases of pontine hemorrhage in which no cause is determined may be caused by capillary telangiectasia.

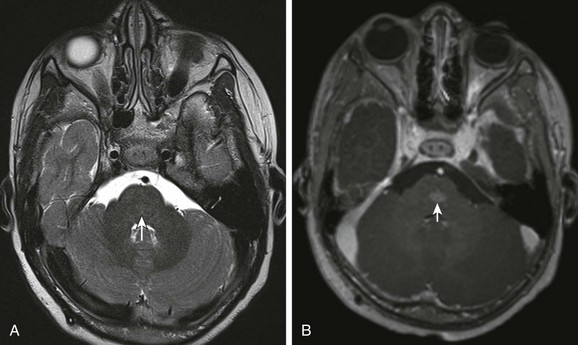

e-Figure 36-6 A 5-year-old with optic pathway glioma incidentally noted to have capillary telangectasia in the pons.

A, Axial T2-weighted image demonstrates nearly imperceptible T2 prolongation in the pontine tegmentum (arrow). B, Postcontrast axial T1-weighted image shows a blush of contrast enhancement without mass effect typical of capillary telangiectasia.

Cavernoma

Cavernomas are localized collections of venous blood.18–21 Cavernomas can occur in isolation (Fig. 36-7) but may also occur very close to DVAs, which suggests a venous origin. Cavernomas may be single or multiple; when multiple, they may be familial, or they may develop in response to radiation therapy for treatment of neuro-oncologic disease.8,21 Cavernomas may be discovered incidentally on imaging or may produce symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage or symptoms due to the mass effect. Pediatric cavernomas behave more aggressively compared with their adult counterparts and are two to three times more likely to hemorrhage.21

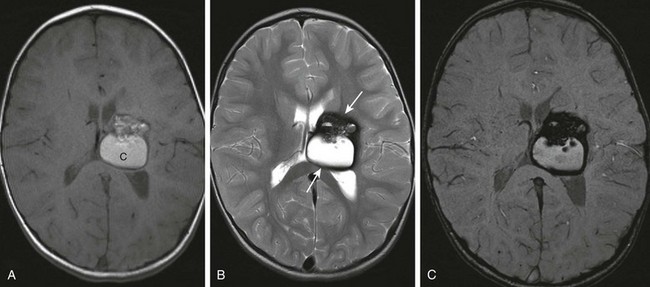

Figure 36-7 A 3-year-old presenting with early left hand preference and speech delay. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large cavernoma involving the left basal ganglia and the thalamus.

A, Axial T1-weighted image reveals a large heterogeneous lesion with areas of T1 shortening suggestive of blood products. B, Axial T2-weighted image demonstrates a low signal intensity rim of hemosiderin (arrows) surrounding the lesion. C, Susceptibility-weighted sequence demonstrates “blooming” of the susceptibility artifact from hemosiderin.

Imaging: On imaging, small cavernomas are typically occult or very subtle on spin-echo imaging but appear as foci of signal voids on long echo, gradient echo, or susceptibility-weighted imaging because of the presence of the magnetic susceptibility effects from associated blood products (see Fig. 36-7).8 Larger lesions are centrally hyperintense on T1-weighed and T2-weighted imaging, with a hypointense rim from the deposition of hemosiderin around the margin of the lesion. Cavernomas are usually found within the brain parenchyma but are occasionally superficial and exophytic, simulating an extra-axial mass.

Developmental Venous Anomaly

DVAs are abnormal veins typically draining normal brain parenchyma. The usual appearance of a DVA is of a cluster of medullary veins radially arranged around the end of an abnormally dilated collecting vein (Fig. 36-8).19,22 DVAs may be small or provide the entire venous drainage for a cerebral lobe or hemisphere. DVAs are usually asymptomatic and discovered incidentally but are occasionally associated with intracranial hemorrhage, especially when associated with a cavernoma. Intracranial DVAs may be seen in association with venous malformation or other vascular anomalies of the scalp and face.22 DVAs are occasionally identified in association with cortical malformations in the evaluation of seizures.23

Figure 36-8 A 15-year-old with remote history of trauma presenting with increasing headaches.

A, Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan shows a prominent intraparenchymal dilated vein in the anterior left frontal lobe (arrow). B, Postcontrast coronal T1-weighted images shows the cluster of radially arranged medullary veins (arrowheads), the “caput medusa,” associated with the abnormally dilated collecting vein (arrow) of a developmental venous anomaly.

Imaging: On contrast-enhanced CT or MRI, DVAs are seen as multiple enhancing medullary veins draining into a single collecting vein; an appearance often referred to as the caput medusa (see Fig. 36-8). DVAs are also visible on catheter angiography and should opacify with contrast at the same time as normal intracerebral veins.19,22

Aneurysms

Intracranial aneurysms in children are a heterogeneous group of diseases and differ in many respects from aneurysms in adults.24–26 Aneurysms are much less common in children than in adults. Pediatric aneurysms account for less than 5% of all aneurysms and are rare in the first year of life.25,27,28 Intracranial aneurysms in children are more likely to be fusiform, involve the posterior circulation, and be larger at the time of presentation than in adults.25 Symptoms of mass effect are at least as common as those from subarachnoid hemorrhage. Aneurysms in children, especially those that are giant or fusiform, may also be discovered incidentally on neuroimaging performed for unrelated reasons. Unlike in adults, in whom aneurysms show a female predominance, in children, boys are more likely to be affected than girls.25 Comorbidities such as collagen vascular disease, polycystic kidney disease, dwarfism, moyamoya disease, and infections are present with roughly 25% of intracranial aneurysms in children.25,29

Saccular aneurysms, the most common form in adults, tend to occur at vessel bifurcations and are believed to be caused by chronic hemodynamic stress on the vessel wall (Fig. 36-9).25 However, because of the time required for vascular stresses to have an effect, saccular aneurysms are much less common in children. Saccular aneurysms tend to occur most frequently at the origin of the posterior communicating artery but are also found at the origin of the anterior communicating artery and basilar artery bifurcation in children. Saccular aneurysms can cause subarachnoid hemorrhage but can also present with symptoms of local mass effect.

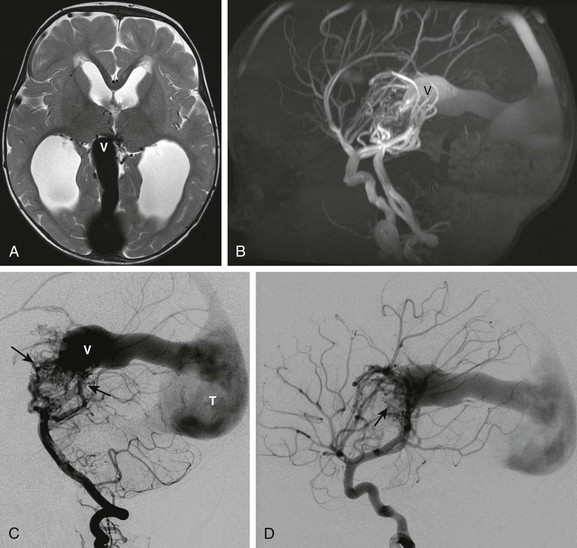

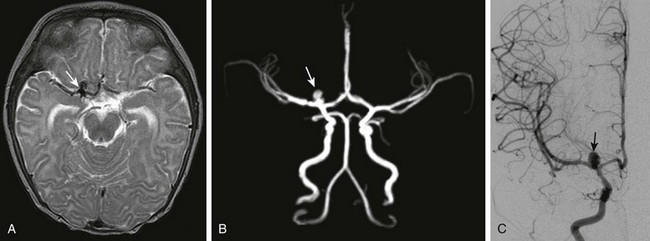

Figure 36-9 A 5-month-old girl who presented with new-onset seizure is found to have aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage on computed tomography.

A, Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates a region of signal void (arrow) near the right internal carotid artery–middle cerebral artery bifurcation. B, Time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography demonstrates flow-related enhancement in a lobulated saccular aneurysm (arrow) involving the proximal M1 segment of the right middle cerebral artery. C, The saccular aneurysm (arrow) is confirmed on the frontal view from a right internal carotid artery injection on catheter angiography.

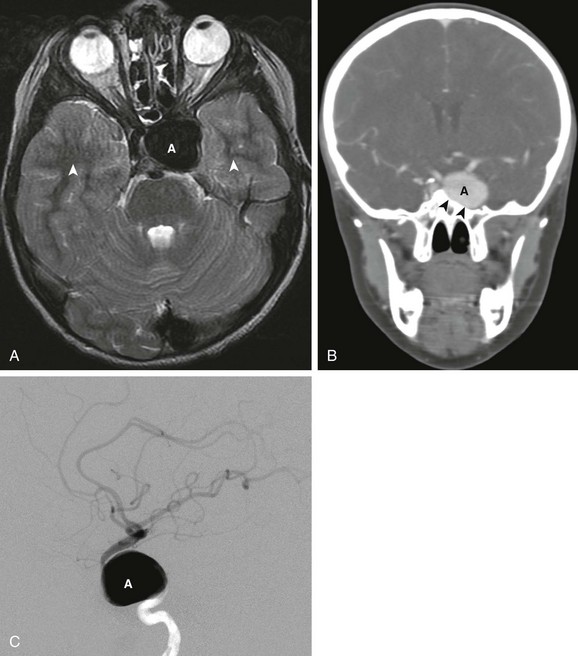

Fusiform aneurysms can be congenital or caused by vessel dissection.25,30 Common sites of involvement in children include the supraclinoid internal carotid artery, the proximal middle cerebral artery, and the basilar artery. Fusiform aneurysms are more likely to result in symptoms due to mass effect (e-Fig. 36-10) but can also result in subarachnoid hemorrhage, particularly when vessel dissection is the underlying cause.

e-Figure 36-10 An 8-year-old boy with new onset of diplopia and cranial nerve VI palsy.

A, Axial T2-weighted images shows a large signal void (A) in the cavernous sinus. Pulsations from the aneurysm produce phase encoding artifact seen as alternating bright and dark bands (arrowheads) extending away from the aneurysm along the phase encode direction. B, Reformatted coronal image from a computed tomographic angiogram (CTA) confirms the presence of a large aneurysm originating from the cavernous portion of the internal carotid artery. The aneurysm (A) has caused remodeling of the adjacent lateral wall of the sphenoid sinus (arrowheads). C, Lateral view of the internal carotid artery injection from a cerebral angiogram confirms a giant aneurysm (A) arising from the cavernous portion of the carotid artery.

Mycotic aneurysms tend to occur along distal vascular segments.24,25 Aneurysms caused by infections are likely to lead to subarachnoid hemorrhage and may increase in size or number rapidly in children. Posttraumatic aneurysms may also occur in distal vascular segments.

Imaging: CT is often the first neuroimaging study performed when an intracranial aneurysm is suspected. Subarachnoid, intraventricular, or parenchymal hemorrhage may be seen on non–contrast-enhanced CT. In giant aneurysms, a hyperdense mass in proximity to the parent artery is typically evident.8 CTA with dynamic imaging during the intravenous administration of contrast with multidimensional reformatting may be used to delineate the relationship of the aneurysm to the parent vessel, the size of the neck of the aneurysm, intra-aneurysmal thrombus, and potential collateral vessels, all factors important in treatment planning.

MRI and MRA are also frequently used in the evaluation of intracranial aneurysms.8 On MRI, the aneurysm may appear as a localized signal void, adjacent to an intracranial vessel or as a fusiform expansion of the vascular signal void. Giant aneurysms may have a lamellated appearance, with alternating areas of T1 shortening and signal void because of the presence of both thrombus and intra-aneurysmal flow. Artifacts from vascular pulsation may be present adjacent to the aneurysm in the phase encode direction of the images (e-Fig. 36-10, A). MRA can be used, in a similar fashion to CTA, to visualize the features of the aneurysm relevant to endovascular or surgical treatment planning. Unlike CTA, MRA does not use ionizing radiation and can therefore be performed without the administration of intravenous contrast; however, it is often limited by flow artifacts in high-flow lesions.

Catheter angiography remains the gold standard for the evaluation of intracranial aneurysms and is often performed with the intent of endovascular treatment during the procedure.22,26 Catheter angiography, especially when combined with rotational imaging, generally shows the anatomic features of the aneurysm as clearly as, or better than, CTA and has the advantage of providing information on the hemodynamics of the aneurysm.

Amlie-Lefond, C, Bernard, TJ, Buillaume, S, et al. Predictors of cerebral arteriopathy in children with arterial ischemic stroke: Results of the International Pediatric Stroke Study. Circulation. 2009;119:1417–1423.

Carvalho, KS, Garg, BP. Arterial strokes in children. Neurol Clin. 2002;20:1079–1100.

Jordan, LC, Hillis, AE. Hemorrhagic stroke in children. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:73–80.

Niazi, TN, Klimo, P, Anderson, RC, et al. Diagnosis and management of arteriovenous malformations in children. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2010;21:443–456.

References

1. Beslow, LA, Jordan, LC. Pediatric stroke: the importance of cerebral arteriopathy and vascular malformations. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1263–1273.

2. Bowen, MD, Burak, CR, Barron, TF. Childhood ischemic stroke in a nonurban population. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:194–197.

3. Lynch, JK, Hirtz, DG, DeVeber, G, et al. Report of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke workshop on perinatal and childhood stroke. Pediatrics. 2002;109:116–123.

4. Smith, ER, Scott, RM. Moyamoya: epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2010;21:543–551.

5. Ibrahimi, DM, Tamargo, RJ, Ahn, ES. Moyamoya disease in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1297–1308.

6. Aviv, RI, Benseler, SM, Silverman, ED, et al. MR imaging and angiography of primary CNS vasculitis of childhood. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:192–199.

7. Burrows, PE, Robertson, RL. Neonatal central nervous system vascular disorders. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1998;9:155–180.

8. Huisman, TA, Singhi, S, Pinto, PS. Non-invasive imaging of intracranial pediatric vascular lesions. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1275–1295.

9. Rubin, D, Santillan, A, Greenfield, JP, et al. Surgical management of pediatric cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1337–1344.

10. Thiex, R, Williams, A, Smith, E, et al. The use of Onyx for embolization of central nervous system arteriovenous lesions in pediatric patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:112–120.

11. Brunelle, F. Brain vascular malformations in the fetus: diagnosis and prognosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003;19:524–528.

12. Lasjaunias, PL, Alvarez, H, Rodesch, G, et al. Aneurysmal malformations of the vein of Galen. Follow-up of 120 children treated between 1984 and 1994. Interv Neuroradiol. 1996;2:15–26.

13. Jankowitz, BT, Vora, N, Jovin, T, et al. Treatment of pediatric intracranial vascular malformations using Onyx-18. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;2:171–176.

14. Zadeh, G, Andrade-Souza, YM, Tsao, MN, et al. Pediatric arteriovenous malformation: University of Toronto experience using stereotactic radiosurgery. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:195–199.

15. Vernimmen, FJ, Slabbert, JP, Wilson, JA, et al. Stereotactic proton beam therapy for intracranial arteriovenous malformations. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:44–52.

16. Barr, RM, Dillon, WP, Wilson, CB. Slow-flow vascular malformations of the pons: capillary telangiectasias? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:71–78.

17. Guibaud, L, Pelizzari, M, Guibal, AL, et al. Slow-flow vascular malformation of the pons: congenital or acquired capillary telangiectasia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:1798–1800.

18. Rigamonti, D, Johnson, PC, Spetzler, RF, et al. Cavernous malformations and capillary telangiectasia: a spectrum within a single pathological entity. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:60–64.

19. San Millan Ruiz, D, Gailloud, P. Cerebral developmental venous anomalies. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1395–1406.

20. Abla, AA, Lekovic, GP, Garrett, M, et al. Cavernous malformations of the brainstem presenting in childhood: surgical experience in 40 patients. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:1589–1599.

21. Acciarri, N, Galassi, E, Giulioni, M, et al. Cavernous malformations of the central nervous system in the pediatric age group. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2009;45:81–104.

22. Burrows, PF, Robertson, RL, Barnes, PD. Angiography and the evaluation of cerebrovascular disease in childhood. Neuroimaging Clin North Am. 1996;6:561–588.

23. Rasalkar, DD, Paunipagar, BK. Developmental venous anomaly associated with cortical dysplasia. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(suppl 1):S165.

24. Lasjaunias, P, Wuppalapati, S, Alvarez, H, et al. Intracranial aneurysms in children aged under 15 years: review of 59 consecutive children with 75 aneurysms. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:437–450.

25. Requejo, F, Ceciliano, A, Cardenas, R, et al. Cerebral aneurysms in children: are we talking about a single pathological entity? Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1329–1335.

26. Sanai, N, Auguste, KI, Lawton, MT. Microsurgical management of pediatric intracranial aneurysms. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1319–1327.

27. Pasqualin, A, Mazza, C, Cavazzani, P, et al. Intracranial aneurysms and subarachnoid hemorrhage in children and adolescents. Childs Nerv Syst. 1986;2:185–190.

28. Proust, F, Toussaint, P, Garnieri, J, et al. Pediatric cerebral aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:733–739.

29. Liang, J, Bao, Y, Zhang, H, et al. The clinical features and treatment of pediatric intracranial aneurysm. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25:317–324.

30. Mizutani, T, Miki, Y, Kojima, H, et al. Proposed classification of nonatherosclerotic cerebral fusiform and dissecting aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:253–259.