chapter 10

Cerebrovascular Disease

Cerebrovascular disease (CVD) is one of the commonest problems encountered in clinical neurology. Hippocrates (460–375 BCE) is credited with introducing the concept of apoplexy (derived from the Greek word for seizure, apoplēxia, in the sense of being struck down) to describe patients with stroke. He is also credited with the statement ‘it is difficult to cure a mild case of apoplexy and impossible to cure a severe case’. This essentially is still the case today and thus the focus should be on primary and secondary prevention. The epidemiology of stroke is discussed in Appendix E.

MINOR STROKE OR TRANSIENT ISCHAEMIC ATTACK: DOES THE DEFINITION MATTER?

Patients with symptoms of cerebral ischaemia that have lasted less than 24 hours have been arbitrarily defined as suffering from a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) while patients with symptoms that last more than 24 hours have been designated as having had a stroke [1]. A term that has come and gone is the reversible ischaemic neurological deficit (RIND), which was defined as symptoms lasting more than 24 hours and less than 6 weeks. However, cerebral infarction can be demonstrated on diffusion-weighted MRI (dwMRI) in patients with symptoms lasting less than 24 hours [2, 3] and may predict the subsequent risk of stroke developing in patients who have had what is currently defined as a TIA [4]. This has led some authorities to recommend a change in the definition of TIA [5, 6].

There are essentially two types of patients with cerebral ischaemia:

• those with minor symptoms that may or may not resolve within a defined period

• those with cerebral ischaemia associated with a severe and disabling neurological deficit.

In the former group prompt assessment and institution of appropriate treatment provides an opportunity to prevent the severe stroke [7]. The risk of stroke after TIA or minor stroke is similar (see Table 10.1), once again suggesting that the separation between TIA and minor stroke is arbitrary and of little clinical value. Thus, all patients with minor symptoms of cerebral ischaemia, regardless of how long the symptoms last, should be treated as a matter of urgency.

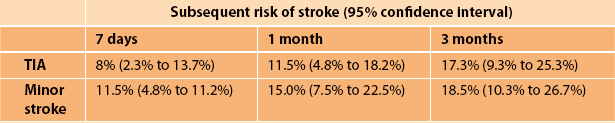

TABLE 10.1

The subsequent risk of stroke after TIA and minor stroke (95% confidence intervals in brackets) [11]

Forty percent of patients who subsequently suffer a stroke after a TIA will do so within the first 7 days; in 17% the TIA will be on the day of the stroke while in 9% it will be on the day prior [8]. Unfortunately, many patients ignore minor symptoms and do not seek urgent medical advice. The opportunity to prevent stroke is lost. The subsequent risk of early stroke after minor cerebral ischaemia is greatest with severe carotid stenosis and in patients with repeated or crescendo TIAs, the ‘capsular warning syndrome’ [9, 10].

The principles of management of patients with CVD are simple and at the same time complex as many patients have more than one potential underlying pathological cause [12]. Patients can present with a cerebral infarct one time and an intracerebral haemorrhage the next [13, 14]. The symptoms and signs of a small intracerebral haemorrhage can be identical to a cerebral infarct of a similar size in the same area and many patients have coexistent medical problems that make the choice of subsequent therapy difficult.

This chapter will discuss the general principles of diagnosis, investigation and management of the more common manifestations of CVD and as such is far from comprehensive. For more detail the reader is referred to one of the many excellent books on the subject [15–20]. There are many websites that also help the clinician keep abreast of the latest developments (e.g. http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/topics/93_reviews.html, http://www.strokeassociation.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=1200037, http://www.strokecenter.org/).

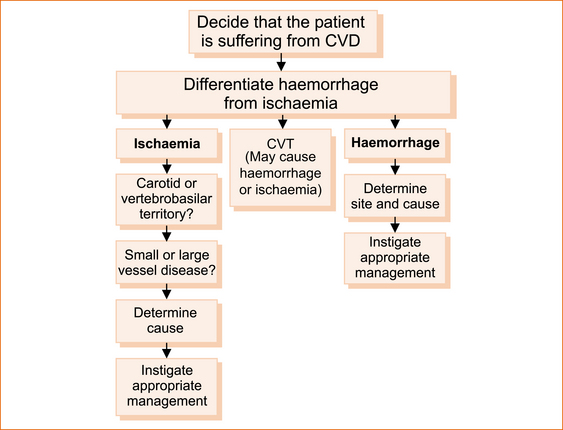

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT

The principles of management are shown in Figure 10.1. As treatment is currently largely disease-specific and different diseases affect different regions, accurate localisation of the problem within the cerebral hemispheres, brainstem or cerebellum is essential. A detailed knowledge of the basic principles of neuroanatomy, which were outlined in Chapter 1, ‘Clinically oriented neuroanatomy’, particularly the concept of the meridians of longitude and the parallels of latitude, is absolutely essential in this respect and a review of Chapter 1 and Chapter 4, in particular the ‘Rule of 4’ of the brainstem would be useful before reading further.

It could be argued that modern diagnostic facilities (and yet to be developed technology), such as CT scans, MRI scans, duplex carotid ultrasound, transthoracic and trans-oesophageal echocardiography, can readily establish if a patient has CVD, differentiate between haemorrhage and infarction, localise the exact site of the lesion, determined if it is lacunar infarction and most likely establish the aetiology. The difficulty with this approach is that not everybody has access to such facilities, the tests are not always positive in patients who are clinically suspected to have CVD (particularly patients with transient symptoms) and both asymptomatic cerebral infarction [21] and asymptomatic carotid stenosis are not uncommon. Therefore, a careful history and, in the presence of abnormal neurological signs, a detailed neurological examination remain the essential tools in management of patients with CVD.

DECIDING THE PROBLEM IS CEREBRoVASCULAR DISEASE

Cerebral vascular disease should be suspected when a patient presents with the sudden or subacute onset of a focal neurological deficit associated with loss of function. The neurological deficit is usually of sudden onset within minutes if not quicker, particularly with an embolic source from the heart or from atherosclerotic vascular disease in one of the major extracranial vessels. Other modes of onset include stepwise stuttering (related to thrombosis rather than embolism) or fluctuating deficit [22, 23].

There a number of common presentations including:

• Vertebrobasilar territory ischaemia

• Ataxia, nausea and vomiting with or without vertigo: cerebellar infarction or haemorrhage

• Dysphagia, dysarthria and ataxia: lateral medullary syndrome (almost always on an ischaemic basis)

• Pure motor hemiparesis affecting arm and leg: paramedian pontine syndrome (almost always on an ischaemic basis)

• Horizontal diplopia looking to one side: unilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia (almost always on an ischaemic basis)

• Hemianopia: occipital infarction (almost always on an ischaemic basis)

• Transient or permanent monocular visual loss: retinal ischaemia (almost always on an ischaemic basis)

• Non-fluent dysphasia and right-sided hemiparesis: dominant hemisphere frontal lobe (almost always on an ischaemic basis)

• Fluent dysphasia with or without a hemianopia: dominant parietal or temporal lobe

• Left-sided weakness and neglect, with or without hemianopia: non-dominant parietal lobe

• Pure motor hemiparesis affecting the face, arm and leg equally: lacunar infarct deep within the cerebral hemisphere

Note: The lacunar syndromes are ischaemic in more than 80% of cases.

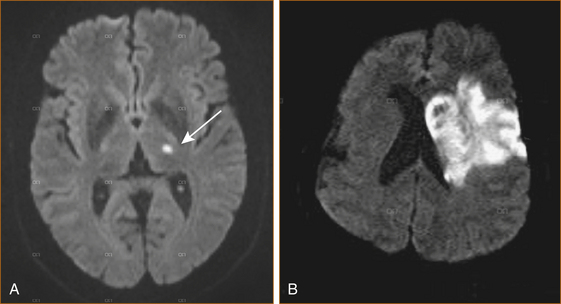

Imaging in cerebrovascular disease

CT scan of the brain is often normal in the first 6 and sometimes up to 24 hours after cerebral infarction; MRI can detect changes as early as 1.5 hours after ischaemia [24]. Diffusion-weighted MRI (dwMRI; see Figure 10.2) has a sensitivity of > 90–95% for detecting early (within the first 6 hours after onset) ischaemic changes as opposed to CT scan with a sensitivity of only 70–75% [1, 25].

DwMRI should be performed within the first week after onset as the changes are transient and this helps to differentiate long-standing old ‘asymptomatic’ ischaemic changes from acute cerebral infarct.

DIFFERENTIATING BETWEEN HAEMORRHAGE AND ISCHAEMIA

• Extradural haematoma (due to rupture of an artery, usually the middle meningeal) and acute subdural haematoma (due to rupture of veins that cross the subdural space) are rarely confused with cerebral ischaemia; both present with the rapid onset of a depressed conscious state.

• A chronic subdural haematoma, on the other hand, can be confused with stroke as it often presents with a non-specific hemiparesis particularly in the elderly [26].

• Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) presents in most patients with the sudden onset of a very severe headache, nausea and vomiting with or without depression of the conscious state. Although SAH is usually discussed under the heading of CVD it rarely presents with a stroke. Occasional patients will have a focal neurological deficit if bleeding occurs into the brain.

• A small intracerebral haemorrhage in the same location within the hemisphere or brainstem as an infarct will result in identical neurological symptoms and signs, and, very rarely, resembles lacunar syndromes [27].

Clues that may help differentiate haemorrhage from infarction

MORE IN KEEPING WITH HAEMORRHAGE

• Early depression of the conscious state and vomiting. Although these two clinical features can occur in brainstem infarction or haemorrhage, both can also reflect a rapid increase in intracranial pressure and should raise the suspicion of intracerebral haemorrhage within the hemisphere.

• Headache in a patient with a pure motor hemiparesis is more suggestive of haemorrhage [28].

• Neither vomiting nor early depression of the conscious state occur with a small haematoma mimicking a lacune. Although more than 80% of patients with pure motor hemiparesis or pure sensory stroke will have a lacunar infarct, a small percentage can be related to intracerebral haemorrhage [29, 30].

MORE IN KEEPING WITH ISCHAEMIA

• Antecedent transient ischaemic attack(s) with the same symptoms prior to the stroke would indicate ischaemia rather than haemorrhage. For example, repeated stereotyped episodes of weakness affecting the face, arm and leg are typical of the capsular warning syndrome, invariably on the basis of lacunar infarction [10, 31].

• The neurological deficit gradually spreads from one part of the body to the rest. For example, if it initially involves the arm and then spreads to the face and subsequently the leg, it is more likely to be ischaemic in origin.

• Spontaneous improvement within the first few hours favours ischaemia rather than haemorrhage.

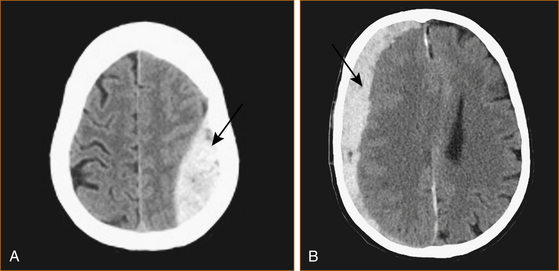

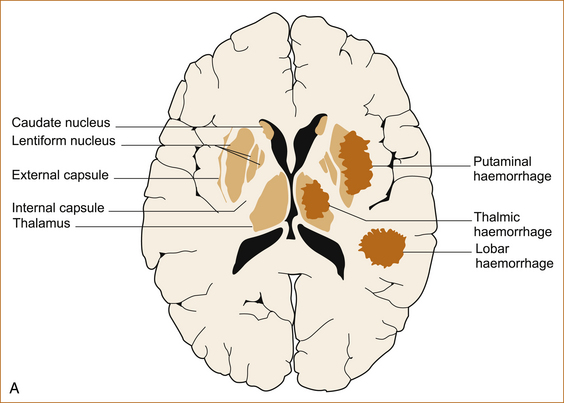

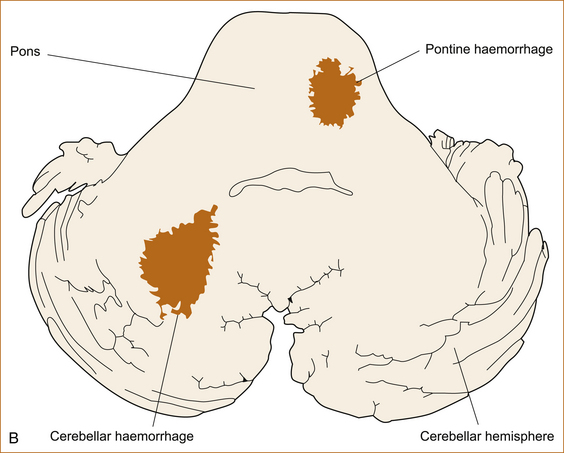

HAEMORRHAGIC STROKE

Intracranial haemorrhage can occur into the extradural, subdural or subarachnoid spaces or be intracerebral or intraventricular (see Figure 10.3). Each site of haemorrhage is associated with a different symptom complex and results from different causes.

Extradural haematoma

Treatment is essentially surgical evacuation but up-to-date recommendations regarding management of head injuries can be found on the National Neurotrauma Society website (http://www.neurotraumasociety.org/book.asp).

Subdural haematoma

Subdural haematoma presents with headache, nausea, confusion and hemiparesis and, if acute, a depressed conscious state. In the elderly, hemiparesis may not be a feature [26]. A classic triad with a reduced conscious state, a dilated pupil ipsilateral to the haematoma (related to a 3rd nerve palsy) and a contralateral hemiparesis indicates life-threatening transtentorial herniation and is a surgical emergency. Occasionally, chronic subdural haematomas are bilateral and may present with an apraxic gait similar to the gait disturbance that occurs with frontal lobe pathology (see Chapter 5, ‘The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum’).

Acute and large chronic subdural haematomas require surgical evacuation, but some chronic subdural haematomas resolve with conservative treatment. Hyperventilation and mannitol are used to reduce raised intracranial pressure.

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

SAH is most often related to a ruptured berry aneurysm (a small out-pouching that looks like a berry and classically occurs at the point of bifurcation of an intracranial artery). Less often it is associated with: an arteriovenous malformation (a congenital disorder of blood vessels in the brain, brainstem or spinal cord that is characterised by a complex, tangled web of abnormal arteries and veins connected by one or more fistulas [abnormal communications]); a non-aneurysmal perimesencephalic haemorrhage [32] where the haemorrhage is centred anterior to the midbrain or pons, with or without extension of blood around the brainstem, into the suprasellar cistern or into the proximal sylvian fissures; or it may be traumatic in origin [33]. The clinical features have been described in Chapter 9, ‘Headache and facial pain’.

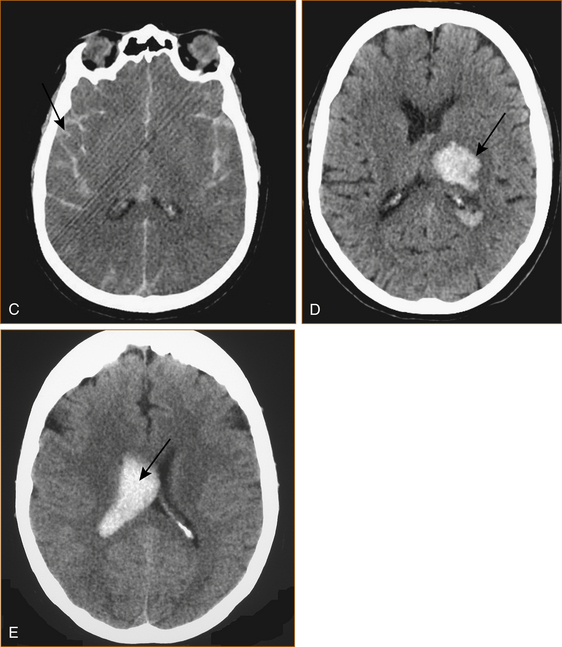

Intracerebral haemorrhage

The commonest cause of intracerebral haemorrhage is rupture of a Charcot–Bouchard aneurysm that forms on very small intracerebral vessels in the setting of long-standing hypertension [34]. The haemorrhages occur in characteristic sites as shown in Figure 10.4 A and B.

Intraventricular haemorrhage

Intraventricular haemorrhage is usually secondary to rupture into the ventricles from intracerebral haemorrhage. Primary intraventricular haemorrhage is very rare and presents with a depressed conscious state or headache and vomiting with or without confusion. Focal neurological signs are absent [35].

ISCHAEMIC CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE

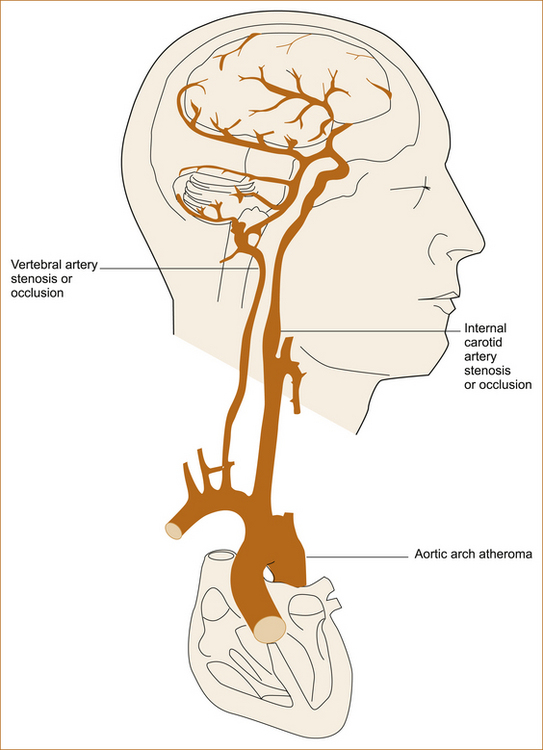

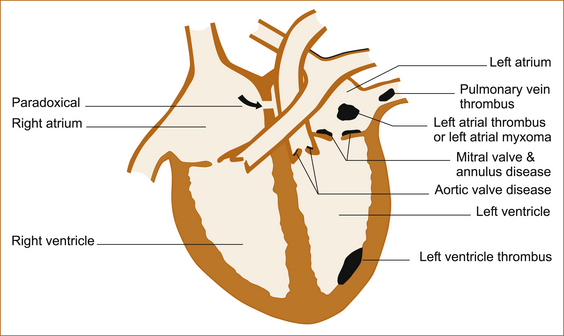

Ischaemic stroke accounts for the great majority of patients with CVD. When managing a patient with ischaemic stroke one needs to consider whether the ischaemia relates to arterial or, much less likely, venous disease. In patients with cerebral ischaemia related to arterial disease it is important to differentiate between small vessel disease within the parenchyma due to occlusion of small perforating vessels and large artery disease that is most likely to be embolic in origin either from the heart, the arch of the aorta or the large arteries in the neck (see Figures 10.6 and 10.7).

Is it large artery, small vessel or cerebral venous disease?

Differentiating between large artery and small vessel disease can be very difficult. Access to diffusion-weighted MRI in the first week after stroke enables differentiation between large vessal and small vessel ischaemia. Small vessel disease is often referred to as the lacunar syndrome where occlusion of very small vessels is usually due to lipohyalinosis and that of slightly larger ones is due to atheromatous or embolic occlusion of the

original penetrating vessel [36]. Although many lacunar syndromes have been described, the advent of sophisticated imaging has revealed that large artery territory infarcts can mimic many of the clinical features of these syndromes.

The most common and more likely features that reflect small vessel disease lacunar syndromes are pure motor hemiparesis and pure sensory loss affecting the contralateral face, arm and leg equally. This usually reflects involvement of the deep hemisphere, in particular the internal capsule and less likely the paramedian brainstem, although in this situation the face may not be affected if the infarct is below the mid pons.

The value of the lacunar syndromes is that they usually identify patients with small vessel disease. The pure motor hemiparesis is where the degree of weakness is similar in the face, arm and a leg and is not associated with any dysphasia, visual field loss or visual inattention; sensory symptoms or signs including sensory inattention; and the three parietal sensory signs described in Chapter 5, ‘The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum’, stereognosis, graphaesthesia or 2-point discrimination. There are a number of other lacunar syndromes, such as ataxic hemiparesis (also referred to as crural paresis and homolateral ataxia), dysarthria clumsy hand syndrome and the sensorimotor stroke, but the same clinical features can occasionally be seen in large artery ischaemia. The advent of CT and MRI has allowed detection of many more lacunar infarcts and highlighted that the clinical features can be very varied, and these have been referred to as ‘atypical lacunar syndromes’ [43].

The risk factors associated with small vessel disease are virtually identical to those associated with large vessel disease, although lacunar infarcts are more common in patients with long-standing hypertension and diabetes. It is not uncommon for patients with a lacunar infarct to have multiple potential causes for ischaemia, such as an ipsilateral internal carotid artery stenosis or a cardiac source for embolism [12].

The presence of dysphasia, visual field disturbances and the cortical sensory signs as described in Chapter 5, ‘The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum’, all indicate involvement of the cortex and, therefore, are related to large artery disease. An epileptic seizure associated with the stroke would also indicate cortical involvement and large artery disease.

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia (see Chapter 4, ‘The cranial nerves and understanding the brainstem’) can occur as an isolated phenomenon and can either be uni- or bilateral. It occurs with ischaemia of the median longitudinal fasciculus and usually in the setting of ostial atheroma affecting a paramedian pontine perforating artery, which may also be associated with more significant basilar artery atheroma.

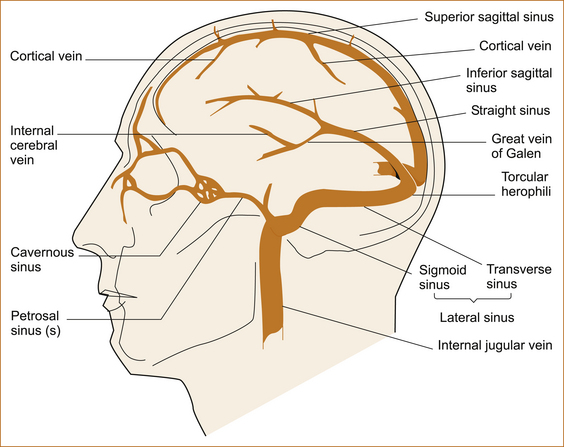

CEREBRAL VEIN THROMBOSIS

Cerebral vein thrombosis is very rare. In the cerebral venous system blood drains from the cortical veins into the superior sagittal sinus and, together with the straight sinus, these drain into the torcular herepholi which then drains into the internal jugular veins via the lateral sinuses (see Figure 10.5).

FIGURE 10.5 Cerebral venous system Reproduced with permission from ‘Cardiogenic stroke’ by PC Gates, HJM Barnett, MD Silver, in Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management, edited by HJM Barnett et al, 1986, Churchill Livingstone, Figure 35.1, p 732 [44]

The resultant clinical syndrome depends on which part of the venous system is affected [44].

• Lateral sinus usually results in intracranial hypertension, resembling idiopathic (IIH) or benign intracranial hypertension (BIH) with raised intracranial pressure causing headache and papilloedema.

• Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis may also result in idiopathic intracranial hypertension but more often it causes severe headache, focal or generalised convulsions and a focal neurological deficit, predominantly hemiparesis due to associated cortical vein thrombosis.

• Cavernous sinus thrombosis presents with unilateral periorbital pain, impaired ocular movements, proptosis (protruding eye) and chemosis (conjunctival oedema and erythema).

• The deep venous system (the straight sinus and its tributaries) is very rare and presents with headache, vomiting, fever and a depressed conscious state.

IF IT IS A LARGE ARTERY DISEASE, WHAT IS THE VASCULAR TERRITORY OF THE CEREBRAL ISCHAEMIA?

At times it can be difficult to differentiate between anterior and posterior circulation ischaemia. As discussed in Chapter 2, ‘The neurological history’, many neurological symptoms and signs are non-specific in terms of their ability to localise a problem to a particular part of the nervous system, while others accurately identify the part of the nervous system affected. A hemiparesis affecting the arm and leg with or without the involvement of the ipsilateral side of the face; unilateral sensory abnormalities affecting the primary sensory modalities of pain, temperature, vibration and proprioception; and dysarthria are all non-specific symptoms with poor localising value, other than to say the lesion is in the CNS above the level of the uppermost signs. If the face, arm and leg are affected this clearly places the problem above the level of the 7th nerve nucleus in the pons but cannot localise it any more accurately. A hemiparesis affecting the arm and a leg in the absence of any other signs can occur with lesions in the contralateral brainstem or hemisphere.

Carotid territory ischaemia: Visual field defects and dysphasia, together with the parietal cortical signs discussed in Chapter 5, ‘The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum’, would indicate the involvement of the cerebral hemispheres.

Vertebrobasilar territory ischaemia: The presence of bilateral weakness or sensory disturbance suggests that the brainstem is affected whereas diplopia or vertigo associated with a weakness or sensory disturbance clearly indicates that the problem is in the brainstem. Nausea, vomiting and an inability to stand are not pathognomonic for CVD, but when these symptoms are due to cerebral vascular disease it almost invariably points to cerebellar infarction or haemorrhage.

IF IT IS LARGE ARTERY DISEASE, WHAT IS THE UNDERLYING PATHOLOGY?

Cerebral ischaemia can result from multiple potential sources, some extremely rare. Figures 10.6 and 10.7 summarise the more common causes from the heart, arch of the aorta and the major extracranial and intracranial vessels. Very rarely, stroke may result from thrombosis within the cerebral venous system or a haematological abnormality. It is useful to consider these two diagrams when dealing with the patient with CVD and always ask where the embolic material has arisen from.

FIGURE 10.6 The heart, major vessels and intracranial vessels Reproduced with permission from Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management, edited by HJM Barnett et al, 1986, Churchill Livingstone, Figure X, p Y [44]

FIGURE 10.7 The heart and sources of emboli Reproduced with permission from Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management, edited by HJM Barnett et al, 1986, Churchill Livingstone, Figure 54.2, p 1088 [44]

The commonest causes of large artery cerebral ischaemia are:

• embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation, less commonly thromboembolism from the left ventricle in the setting of myocardial infarction or a cardiomyopathy

• atheroma or thromboembolism from the arch of the aorta or the major extracranial vessels in patients suffering from atherosclerotic vascular disease.

The origin of the internal carotid artery is a common site for atherosclerotic vascular disease that can produce severe stenosis or even result in occlusion when superimposed thrombosis occurs. Cerebral ischaemia is rare in adults less than 40 years of age (unless they suffer from hypertension and diabetes when atherosclerotic vascular disease is the most likely cause of cerebral ischaemia); when it does occur extracranial arterial dissection needs to be considered. A patent foramen ovale is considered by some authorities to be a source of embolism and a cause of stroke in young adults [45, 46] and thrombus has been visualised traversing the patent foramen ovale [47], although coexistent deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is found in as few as 5% of patients with cerebral ischaemia and a patent foramen ovale.

A complete list of the causes of cerebral ischaemia is beyond the scope of this book and the interested reader is referred to more comprehensive texts. In many patients with cerebral ischaemia, particularly younger patients, current investigations are unable to elucidate the cause in as many as 30–40% [48]. In some patients with ‘cryptogenic stroke’ atrial fibrillation is subsequently detected [49].

There are the two common carotid arteries with their major branches, the internal and external carotid, with the anterior and middle cerebral arteries arising from the internal carotid and the two vertebral arteries joining intracranially to form the basilar artery. Major branches arise from the vertebral and basilar arteries to supply the lateral brainstem and cerebellum. These include the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (usually arises from the vertebral), the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, the superior cerebellar artery and the posterior cerebral arteries (all branches of the basilar).

THREE STROKE SYNDROMES THAT SHOULD NOT BE MISSED

Cerebellar haemorrhage or infarction

Patients present in a variety of ways; in general, it is an inability to walk associated with nausea and vomiting with or without vertigo and headache. In some patients the vomiting is so severe it results in a Mallory–Weiss tear of the oesophagus and the patient presents with haematemesis. In patients with posterior inferior cerebellar artery territory infarcts, a triad of vertigo, headache and gait imbalance predominates at stroke onset. In patients with superior cerebellar artery infarcts, gait disturbance predominates at onset; vertigo and headache are significantly less common [50]. If the infarct also involves the lateral brainstem, in addition to the features resulting from infarction of the cerebellum, there will be cranial nerve involvement, for example with the involvement of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery there is often a lateral medullary syndrome.

Note: Lateral medullary syndrome also occurs with vertebral artery disease [51].

Symptomatic severe carotid stenosis

Symptomatic carotid stenosis of greater than 70% is associated with a 26% risk of stroke in the ensuing 18 months [52, 53]. There is a significant risk of recurrent ischaemia in the first week after the initial symptoms and assessment should NOT be delayed. The risk of stroke prior to endarterectomy in the OXVASC subpopulation (where there was a significant delay in performing endarterectomy with only 43% of patients undergoing endarterectomy by 12 weeks) with ≥ 50% stenosis was 21% (95% CI: 8 to 34%) at 2 weeks and 32% (95% CI: 17 to 47%) at 12 weeks, and half the strokes were disabling or fatal [54]. Contralateral carotid occlusion increases the risk of early recurrence [55].

Patients with carotid stenosis may present with a severe stroke without warning; however, a number will have an antecedent TIA that provides an opportunity to intervene and prevent the stroke. Carotid stenosis should be suspected in patients who present with unilateral amaurosis fugax and/or symptoms of hemisphere ischaemia particularly if there is an ipsilateral carotid bruit. Focal involvement of one limb or dysphasia with symptoms lasting longer than 1 hour are more likely to indicate the presence of a severe carotid stenosis than a lacunar syndrome [56–58]. Carotid stenosis is more common in patients with diabetes, those who smoke [59] and if there is coexistent coronary artery disease.

Basilar artery stenosis

The prognosis of basilar artery thrombosis is extremely poor and, although basilar artery occlusion may be the first presenting symptom, two-thirds of these patients experience in the weeks to months prior to the thrombosis a flurry of episodes of transient cerebral ischaemia that become more frequent just prior to infarction [60]. Tetraparesis is rare and occurs more frequently when the basilar artery syndrome is related to embolism rather than stenosis and superimposed thrombosis. Patients can present with any combination of symptoms reflecting involvement of the brainstem including a depressed conscious state, weakness, sensory abnormalities, vertigo, nausea and vomiting and diplopia [60]. Once again vertigo, diplopia and bilateral symptoms clearly indicate the involvement of the brainstem, but it is important to remember that not all patients with severe basilar artery stenosis will have symptoms that clearly indicate that the problem is in the brainstem. It is repeated stereotyped TIAs that should alert the clinician to the possibility of a tight stenosis and prompt urgent investigations.

THREE OF THE ‘MORE COMMON’ RARER CAUSES OF STROKE, PARTICULARLY IN THE YOUNG

Extracranial arterial dissection

Dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries is one of the more common causes of stroke in young patients. In 50% of patients there will be not be any history of head or neck trauma; it can occur even during coughing or sneezing. This author has seen patients who developed arterial dissection by simply turning their head.

Patent foramen ovale

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is present in up to 27% of the general population, and in 2% of the population is associated with an atrial septal aneurysm (ASA), which is a bulging of the atrial wall 1.2–15 cm into the left atrium. The presence of an ASA or a large right-to-left shunt has been reported to increase the risk of stroke. In a large French study [46] the risk of recurrent cerebral ischaemia was 2.3% with PFO alone and 15.2% if there was also an ASA. Other studies have failed to confirm the increased risk with an ASA [65]. Coexistent venous thrombus is seen in approximately 5–6%.

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

Antiphospholipid (APL) antibodies were first described in 1906 [67] and are a heterogeneous group of autoantibodies directed against phospholipid-binding proteins. They can be broadly categorised into those antibodies that prolong phospholipid-dependent coagulation assays, known as lupus anticoagulants (LA), or anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL), which target a molecular congener of cardiolipin.

APL antibodies may cause various neurological diseases by vascular and immune mechanisms.

APL antibody syndrome is the presence of these antibodies in patients with arterial or venous thrombosis. The association between APL antibodies and stroke is strongest for young adults less than 50 years of age [68]. Recurrent thrombotic events are common despite treatment [69]. APL antibodies should be tested in all young patients, particularly if there is a combination of arterial and venous thrombosis and, although the association with stroke in the elderly is less convincing, in older patients with no apparent cause of stroke. Recurrent cerebral ischaemia is common and the risk is greatest with higher IgG anticardiolipin titres [70].

MANAGEMENT OF ISCHAEMIC CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE

The principles of management are discussed below. However, treatment will evolve rapidly and the reader should seek up-to-date information and guidelines from the American Heart Association stroke website and other websites dedicated to cerebral vascular disease such as the Cochrane collaboration and the stroke trials registry (http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3004586, http://www.strokecenter.org/trials/, http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/topics/93_reviews.html).

Essentially, the management of patients with cerebral ischaemia involves treatment at the time of the initial episode of cerebral ischaemia and secondary prevention through risk factor modification and cause-specific therapy adapted to the individual patient on the basis of their coexistent medical conditions, concurrent medications and social circumstances.

MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE ISCHAEMIC STROKE

The American Heart Association Stroke Council has issued extensive guidelines for all aspects of the early management of patients with ischaemic stroke (which may be accessed on the AHA website, http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3004586) [72].

Initial urgent bedside clinical assessment

• The pulse (looking for atrial fibrillation), temperature (that may indicate the presence of sepsis) and respiratory rate (that if elevated may indicate pneumonia) should be evaluated.

• The blood pressure should be measured (checking for the very rare case of hypertensive encephalopathy with a diastolic pressure > 120 mmHg and to determine if the blood pressure needs to be treated prior to considering thrombolysis).

• The heart should be auscultated to check for a cardiac murmur (that could be a potential case of infective endocarditis, < 1% of cases per year).

• An urgent ECG should be performed (to detect atrial fibrillation [AF] or the asymptomatic myocardial infarct, the latter particularly in patients with diabetes).

Investigations that should be performed immediately

• Non-contrast CT or MRI of the brain. In most instances CT is the only imaging modality available, but it can provide sufficient information to determine emergency management. The CT scan will rule out intracranial haemorrhage and other pathology such as tumours that may mimic a stroke.

• Full blood examination, platelet count, C-reactive protein (CRP) and ESR. Anaemia and an elevated ESR should alert the clinician to the possibility of endocarditis and an altered platelet count may indicate much rarer pathological processes such as thrombotic thombocytopaenic purpura (TTP) or essential thrombocytosis.

• Blood glucose. Asymptomatic diabetes is not uncommon and rarely hypoglycaemia may present with a focal deficit mimicking a stroke.

• Serum electrolytes and renal function tests. Many patients are on diuretics that may cause hyponatraemia or hypokalaemia, and impaired renal function will influence the choice of antihypertensive medication.

• Prothrombin time/international normalised ratio (PT INR). Particularly necessary in patients on warfarin.

• Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). In young patients as a screening test for the lupus anticoagulant (APPT is elevated).

• Oxygen saturation. Some patients may have suffered clinically unrecognised aspiration and also because many patients have been heavy smokers and have coexistent chronic obstructive airways disease.

Subsequent investigations

ASSESSING THE INTERNAL CAROTID ARTERY

The modality of choice for non-invasive carotid artery assessment depends largely on the clinical indications for imaging and the skills available in individual centres. Although digital subtraction angiography was the gold standard imaging technique used in the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial, currently most screening would be done with carotid duplex ultrasonography (DUS) that has a sensitivity of 98% and specificity of 88% for detecting > 50% ICA stenosis and 94% and 90%, respectively, for detecting > 70% ICA stenosis [73]. DUS can miss severe carotid stenosis. As imaging technology advances, it is possible that CT angiography or MR angiography may replace DUS. CT angiography and MR angiography are not suitable for all patients because of contraindications. CT angiography has a sensitivity and specificity for detecting carotid occlusion of 97% and 99%, respectively; however, the diagnostic accuracy is lower for severe stenosis in the range of 70–99% with a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 93%. The sensitivity and specificity of MR angiography is very dependent on the technique employed and currently is not adequate enough to replace the other imaging modalities.

LOOKING FOR A CARDIAC SOURCE OF EMBOLISM

In patients with large artery ischaemia and normal extracranial vessels, a more proximal source needs to be considered. A recent review [74] discusses the diagnostic yield of a ‘cardiac workup’.

Cardiac monitoring: This is recommended in patients with large artery ischaemia who are not in AF, particularly if there is no significant stenosis in the major extracranial vessels. AF was found in 7% of 465 patients monitored for 54.55 ± 35.74 hours [75]. In one study of 36 patients with cryptogenic stroke where 20 underwent 30-day event monitoring, 4 (20%) were found to have previously undiagnosed AF [49]. AF is more likely to be present in patients ≥ 62 years of age, with an NIHSS ≥ 8, large artery ischaemia without extracranial large artery stenosis and a dilated left atrium as detected on transthoracic echocardiogram [76]. It is appropriate to monitor patients with large artery territory ischaemia with normal arteries to that territory for several days while there are other reasons for them to be an inpatient.

Echocardiography: Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) will detect abnormalities of the left ventricle and enlargement of the left atrium, while transoesophageal (TOE) is more sensitive at detecting PFO, infective endocarditis vegetations and aortic arch atheroma. The latter is more invasive and may cause oesophageal rupture in elderly patients. At this point in time there is no consensus on who should have structural imaging of the heart, with some advocating all patients and others recommending a more restricted use. As there is no convincing evidence regarding the treatment of PFO or aortic arch atheroma while detection of a cardiomyopathy or dyskinetic anterior left ventricular wall would indicate the use of anticoagulation, it would seem reasonable to perform TTE in patients with large artery territory ischaemia and normal extracranial vessels, particularly if they have preexisting cardiac disease where the yield is higher. TOE should be performed in patients with suspected infective endocarditis and patients < 50 years of age to look for a PFO.

General supportive care and treatment of acute complications

• Airway support and ventilator assistance are recommended for patients with a decreased consciousness or who have bulbar dysfunction causing compromise of the airway.

• Hypoxic patients with stroke should receive supplemental oxygen.

• Patients should be screened for dysphagia and placed nil orally if they are unable to swallow. If swallowing does not improve a nasogastric tube may need to be inserted.

• The management of arterial hypertension remains controversial but it needs to be less than 185/110 mmHg if thrombolysis is contemplated.

• Hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia should be treated.

• Prevention of DVT with prompt initiation of subcutaneous anticoagulation on the day of admission should be undertaken in all patients.

• Fever should prompt a septic workup. Sources of fever should be treated and antipyretic medications should be administered to lower temperature in febrile patients.

• Patient’s chest and IV sites should be examined daily as chest infections and aspiration pneumonia (even in patients who are nil orally and who have nasogastric tubes inserted) occur in the first few days after stroke.

• Intravenous site and urinary tract infections are common complications of patients with ischaemic stroke and require prompt attention and IV site infections or thrombosis of the vein are not uncommon.

• Seizures either focal or generalised may occur in a small percentage of patients with cortical cerebral ischaemia, usually within the first 24 hours.

• Myocardial ischaemia is seen in the occasional patient.

• Pulmonary embolism may occur despite prophylactic anticoagulants.

Dysphagia screen

Many patients with stroke develop dysphagia that predisposes them to potential aspiration pneumonia. The dysphagia is often transient but it may persist for some days to weeks and patients will require nasogastric feeding. In some patients swallowing does not recover and these patients require long-term feeding with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. Although controversial [77], the risk of aspiration may be reduced with dysphagia screening [78]. Most stroke units would perform a dysphagia screen on all patients and, if the patient fails the screen, they are placed nil orally until a speech therapist undertakes a formal assessment of swallowing as soon as possible.As dysphagia is often temporary, it is not unreasonable to defer insertion of a nasogastric tube until it is clear that improvement is not occurring.

Note: The Barwon Health Stroke unit has a speech therapist 7 day per week. The Barwon Health Dysphagia Screen is shown in Appendix G.

Thrombolytic therapy

Intravenous thrombolysis with t-PA (0.9 mg/kg with a maximum dose of 90 mg) is recommended in patients with cerebral ischaemia who meet very stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Appendix F) [72, 79–81]. Although the time window has been extended beyond the original 3 hours [82], IV t-PA should be administered as soon as possible after the onset of stroke. Refer to Appendix E for details.

Symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage including fatal haemorrhage is the most dreaded complication of this therapy and occurs in 1.7–7.3% of patients (depending on how symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage is defined) [79, 83].

The very stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, in particular the narrow time window, imply that only a small percentage of patients will benefit from thrombolytic therapy. Similarly, clot retrieval devices [84, 85], stenting [86] and intra-arterial t-PA [87] require massive resources, are confined to large academic centres and are unlikely to become gold standard treatments in the near future. It is hoped that one day neuroprotection will allow a longer period before recanalisation is attempted with thrombolytic therapy.

Antiplatelet agents

The International Stroke Trial (IST) [88] and the Chinese Acute Stroke Trial (CAST) [89] have both demonstrated a non-significant trend towards a better outcome with antiplatelet agents. A combined analysis of both trials demonstrated a statistically significant benefit in terms of reduced incidence of recurrent stroke with aspirin given in the first 24–48 hours of acute stroke. It should not be given in the first 24 hours to patients undergoing thrombolysis. The recommended dose is aspirin 160–300mg [90]. Ticlopidine, clopidogrel and dipyridamole have not been evaluated in acute stroke.

URGENT MANAGEMENT OF SUSPECTED TIA OR MINOR ISCHAEMIC STROKE

One of the most challenging aspects is the urgent management of minor ischaemic stroke or TIA. A number of patients do not recognise that minor neurological symptoms may represent a warning of a more severe stroke and do not seek medical attention. In other patients the interval between the initial symptom and the subsequent severe cerebral infarct is brief and therefore the time to intervene is limited. At times it is impossible to be certain clinically whether the symptoms represent cerebral ischaemia and thus prompt emergency investigations or whether it is a less urgent problem when investigations could wait. Finally, having decided the patient has cerebral ischaemia the question arises as to whether one can gain access to the urgent imaging required or should the patient be admitted to hospital. All these questions are not readily answered.

Patients with suspected minor cerebral ischaemia should be assessed as a matter of urgency. The urgent bedside assessment is the same as for more severe ischaemic stroke (see ‘Initial urgent bedside clinical assessment’ under ‘Management of acute ischaemic stroke’) and includes pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, temperature, an urgent ECG, CT of the brain and, if carotid territory ischaemia, imaging (if there is uncertainty about whether it is carotid territory then err on the safe side and obtain urgent imaging because the consequences of missing a severe symptomatic internal carotid stenosis are potentially disastrous). The earliest risk of recurrence is in patients with large artery atherosclerotic vascular disease, accounting for more than one-third of recurrent cerebral ischaemia within the first 7 days [9]. Carotid territory should be imaged on the same day as half of all recurrent strokes during the 7 days after a TIA occur in the first 24 hours [92].

A vexed question is whether to admit the patient to hospital. Although currently proven therapy can be administered on an outpatient basis, some would argue that in the high risk group admission to hospital provides an excellent opportunity for the urgent detection of subsequent cerebral infarction and prompt administration of thrombolytic therapy. In recent years a scoring system, referred to as the ABCD2 score (see Table 10.2), based on five factors has been advocated as a technique to detect patients who require admission because of a greater likelihood of early recurrence of cerebral ischaemia [93]. Admission is advised if the score is 4 or more, while those with a score of less than 4 can be investigated as outpatients. However, in a recent study of 1176 patients in the SOS_TIA registry, the ABCD2 score < 4 would have missed 20% of patients requiring urgent treatment for carotid stenosis > 50%, intracranial stenosis, AF and other major cardiac causes of embolism [94]. Those authors advocate a DSU as part of the emergency assessment. Patients with recurrent TIAs should be admitted, as should patients with severe carotid stenosis with a view to urgent endarterectomy.

TABLE 10.2

The ABCD2 score for prediction of 2-day stroke risk [93]

| Factor | Points |

| Age ≥ 60 years | 1 |

| Blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg | 1 |

| Unilateral weakness | 2 |

| Speech impairment without weakness | 1 |

| Duration of event ≥ 60 min | 2 |

| Duration of event = 10–59 min | 1 |

| Diabetes | 1 |

SECONDARY PREVENTION

The epidemiology and primary prevention of stroke are discussed in Appendix E. The same principles apply in secondary prevention (treatment after the onset of symptoms of cerebral vascular disease). Risk factor modification, such as treatment of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, asymptomatic carotid stenosis, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, obesity and smoking, is just as relevant.

Antiplatelet, anticoagulant and surgical therapy for secondary prevention

Unless there are contraindications, all patients with cerebral ischaemia in the absence of the specific cardiac causes discussed below should receive aspirin. There is considerable debate about the actual dose that should be prescribed. The early trials [95, 96] used large doses in the order of 1200 mg/day. The addition of dipyridamole to aspirin was found to be superior to aspirin alone [97].

Current recommendations as first-line treatment from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on stroke [66] include:

Clopidogrel has been shown to be equivalent to aspirin/dipyridamole [99], but combination therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel is not recommended because of an increased risk of haemorrhage [101]. The problem with dipyridamole is that a number of patients cannot tolerate it because of headache. The headache may resolve if the drug is introduced at a small dose and increased gradually and the patient can persevere for a few days to weeks despite the headache [102].

There is an increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage complicating head trauma with clopidogrel, which is not seen with aspirin [103].

Although warfarin is often prescribed in patients with recurrent events on antiplatelet therapy, it has not been shown to be more beneficial than aspirin in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease [104].

ENDARTERECTOMY FOR SYMPTOMATIC CAROTID STENOSIS

The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) [105] and the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) [106] both demonstrated a very significant benefit (absolute risk reduction of 17% and 14%, respectively) of carotid endarterectomy in patients with a 70% or more stenosis of the internal carotid artery. The benefit for patients with a symptomatic 50–69% stenosis was modest, with an absolute risk reduction of only 1% [107].

The European Society of Vascular Surgeons (ESVS) published guidelines recommend [108]:

The complications rates for endarterectomy have varied enormously from one institution to another, from as low as 0% to as high as 21% [109, 110]. An acceptable complication rate for patients with symptomatic stenosis is < 6%.

CAROTID ARTERY STENTING

Symptomatic carotid stenosis: The ESVS published guidelines [108] recommend that carotid artery stenting (CAS) should be performed only in patients at high-risk for CEA, in high-volume centres with documented low perioperative stroke and death rates or inside a randomised controlled trial. CAS should be performed under dual antiplatelet treatment with aspirin and clopidogrel.

In one trial of less than 350 patients with severe carotid artery stenosis and increased surgical risk, no significant difference could be shown in long-term outcomes between patients who underwent CAS with an emboli-protection device and those who underwent endarterectomy [111]. In a larger trial [112] of 1214 patients, carotid angioplasty with stenting was not shown to be inferior to CEA in terms of the number of subsequent events of cerebral ischaemia after a short follow-up of only 2 years. Although there is some uncertainty regarding the accuracy of DSU in determining the degree of stenosis in patients with an in situ stent, the re-stenosis rate was higher in the stent group.

Others would argue that CAS, despite the attraction of its less invasive nature, has not been shown to be as effective in the long term as CEA in patients who are not at increased surgical risk and that CAS should be reserved for patients with medical or surgical contraindications to CEA until such time that it has been proven to be as effective in both the short and long term [113]. The results of the International Carotid Stenting Study presented recently have shown that endarterectomy is superior to stenting [114]. The 30-day periprocedural stroke rate was 58 (6.7%) in the stenting group versus 27 (3.2%) in the endarterectomy group. This risk was not influenced by the use of protection devices. The 120-day risk of stroke, myocardial infarction or death was 8.3% versus 5.1%, respectively.

A recent meta-analysis [115] has concluded that carotid endarterectomy is superior to CAS for short-term outcomes, mainly due to an increase in non-disabling strokes in stented patients. An accompanying editorial [116] concluded that CAS is not yet ready to replace endarterectomy.

Intracranial stenosis: Although intracranial stenting appears to be feasible, adverse events vary widely, there is a high rate of re-stenoses and no clear impact of new stent devices on outcome. A recent review concluded that the widespread application of intracranial stenting outside the setting of randomised trials and in inexperienced centres currently does not seem to be justified [86].

MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH ANTICOAGULATION-ASSOCIATED INTRACRANIAL HAEMORRHAGE

There is a little scientific evidence in the literature to provide guidance in the management of this situation. Temporary interruption of anticoagulation therapy seems safe for patients with intracranial haemorrhage and mechanical heart valves without previous evidence of systemic embolisation. For most patients, discontinuation for 1–2 weeks should be sufficient to observe the evolution of a parenchymal haematoma, to clip or coil a ruptured aneurysm or to evacuate an acute subdural haematoma [115]. Others have argued for a 6-month cessation of anticoagulation [116]. Some would recommend heparin during the period of warfarin withdrawal [117].

The most sensible approach would appear to be to reverse the anticoagulant immediately with either vitamin K or fresh frozen plasma and withhold anticoagulation for at least 1–2 weeks. The decision to resume anticoagulation after 3–4 weeks would depend on the underlying risk for thromboembolism, but it is recommended that patients be monitored more carefully and the PT INR be kept at the lower end of the therapeutic range [66]. (Note: If the intracranial haemorrhage is SAH related to rupture of an aneurysm, the anticoagulation should not be resumed until the aneurysm is secured.) In patients with artificial heart valves, the risk is so high that anticoagulation must be recommenced and, in patients with AF and a high CHADS2 score, the benefits would outweigh the risks. Anticoagulation can be safely resumed in patients with intracerebral haemorrhage.

REFERENCES

1. Ad hoc committee established by the Advisory Council for the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health. A classification and outline of cerebrovascular diseases. II. Stroke. 1975;6(5):564–616.

2. Engelter, S.T., et al. The clinical significance of diffusion-weighted MR imaging in stroke and TIA patients. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138(49–50):729–740.

3. Kidwell, C.S., et al. Diffusion MRI in patients with transient ischemic attacks. Stroke. 1999;30(6):1174–1180.

4. Purroy, F., et al. Higher risk of further vascular events among transient ischemic attack patients with diffusion-weighted imaging acute ischemic lesions. Stroke. 2004;35(10):2313–2319.

5. Easton, J.D., et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2276–2293.

6. Albers, G.W., et al. Transient ischemic attack – proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1713–1716.

7. Rothwell, P.M., et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): A prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1432–1442.

8. Rothwell, P.M., Warlow, C.P. Timing of TIAs preceding stroke: Time window for prevention is very short. Neurology. 2005;64(5):817–820.

9. Lovett, J.K., Coull, A.J., Rothwell, P.M. Early risk of recurrence by subtype of ischemic stroke in population-based incidence studies. Neurology. 2004;62(4):569–573.

10. Rothrock, J.F., et al. ‘Crescendo’ transient ischemic attacks: Clinical and angiographic correlations. Neurology. 1988;38(2):198–201.

11. Coull, A.J., Lovett, J.K., Rothwell, P.M. Population based study of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke: Implications for public education and organisation of services. BMJ. 2004;328(7435):326.

12. Moncayo, J., et al. Coexisting causes of ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(8):1139–1144.

13. Wang, H.C., et al. Risk factors for acute symptomatic cerebral infarctions after spontaneous supratentorial intra-cerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol. 2009;256(8):1281–1287.

14. Ariesen, M.J., et al. Predictors of risk of intracerebral haemorrhage in patients with a history of TIA or minor ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(1):92–94.

15. Caplan, L.R. Posterior circulation disease: Clinical findings, diagnosis, and management. Boston: Blackwell Science; 1996;vol 1.

16. Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, Klawans HL (eds). Vascular diseases: Handbook of clinical neurology, vol. 53–55. Elsevier Science Publishers; 1988.

17. Bogousslavsky, J., Caplan, L.R. Uncommon causes of stroke. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

18. Bogousslavsky, J., Caplan, L.R. Stroke syndromes, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

19. Barnett, H.J.M., et al. Stroke, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management, 3rd edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

20. Warlow, C.P., et al. Stroke: A practical guide to management. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2001.

21. Kempster, P.A., Gerraty, R.P., Gates, P.C. Asymptomatic cerebral infarction in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 1988;19(8):955–957.

22. Bogousslavsky, J., Van Melle, G., Regli, F. The Lausanne Stroke Registry: Analysis of 1,000 consecutive patients with first stroke. Stroke. 1988;19(9):1083–1092.

23. Mohr, J.P., et al. The Harvard Cooperative Stroke Registry: A prospective registry. Neurology. 1978;28(8):754–762.

24. Kucinski, T., et al. Correlation of apparent diffusion coefficient and computed tomography density in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2002;33(7):1786–1791.

25. Saur, D., et al. Sensitivity and interrater agreement of CT and diffusion-weighted MR imaging in hyperacute stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(5):878–885.

26. Patrick, D., Gates, P.C. Chronic subdural haematoma in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1984;13(6):367–369.

27. Mori, E., Tabuchi, M., Yamadori, A. Lacunar syndrome due to intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1985;16(3):454–459.

28. Arboix, A., et al. Haemorrhagic pure motor stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(2):219–223.

29. Arboix, A., et al. Clinical study of 99 patients with pure sensory stroke. J Neurol. 2005;252(2):156–162.

30. Arboix, A., et al. Clinical study of 222 patients with pure motor stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(2):239–242.

31. Donnan, G.A., et al. The capsular warning syndrome: Pathogenesis and clinical features. Neurology. 1993;43(5):957–962.

32. Schwartz, T.H., Solomon, R.A. Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1996;39(3):433–440. [discussion 440].

33. van Gijn, J., Rinkel, G.J. Subarachnoid haemorrhage: Diagnosis, causes and management. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 2):249–278.

34. Sutherland, G.R., Auer, R.N. Primary intracerebral hemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13(5):511–517.

35. Gates, P.C., et al. Primary intraventricular hemorrhage in adults. Stroke. 1986;17:872–877.

36. Fisher, C.M. Lacunar strokes and infarcts: A review. Neurology. 1982;32(8):871–876.

37. Derdeyn, C.P., et al. The International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT): A position statement from the Executive Committee of the American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology and the American Society of Neuroradiology. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(7):1404–1408.

38. Broderick, J., et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in adults: 2007 update: A guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, High Blood Pressure Research Council, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Stroke. 2007;38(6):2001–2023.

39. Rincon, F., Mayer, S.A. Clinical review: Critical care management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care. 2008;12(6):237.

40. Qureshi, A.I., Mendelow, A.D., Hanley, D.F. Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet. 2009;373(9675):1632–1644.

41. Misra, U.K., et al. Mannitol in intracerebral hemorrhage: A randomized controlled study. J Neurol Sci. 2005;234:41–45.

42. Elijovich, L., Patel, P.V., Hemphill, J.C., 3rd. Intracerebral hemorrhage. Semin Neurol. 2008;28(5):657–667.

43. Arboix, A., et al. Clinical study of 39 patients with atypical lacunar syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(3):381–384.

44. Gates, P.C., Barnett, H.J.M., Silver, M.D. Cardiogenic Stroke. In: Stroke: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1986:1085–1110.

45. Lechat, P., et al. Prevalence of patent foramen ovale in patients with stroke. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(18):1148–1152.

46. Mas, J.L., et al. Recurrent cerebrovascular events associated with patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm, or both. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(24):1740–1746.

47. Srivastava, T.N., Payment, M.F. Images in clinical medicine: Paradoxical embolism–thrombus in transit through a patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(10):681.

48. Guercini, F., et al. Cryptogenic stroke: Time to determine aetiology. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(4):549–554.

49. Elijovich, L., et al. Intermittent atrial fibrillation may account for a large proportion of otherwise cryptogenic stroke: A study of 30-day cardiac event monitors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18(3):185–189.

50. Kase, C.S., et al. Cerebellar infarction. Clinical and anatomic observations in 66 cases. Stroke. 1993;24(1):76–83.

51. Kim, J.S. Pure lateral medullary infarction: Clinical-radiological correlation of 130 acute, consecutive patients. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 8):1864–1872.

52. European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Collaborative Group. MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial: Interim results for symptomatic patients with severe (70–99%) or with mild (0–29%) carotid stenosis. Lancet. 1991;337(8752):1235–1243.

53. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(7):445–453.

54. Fairhead, J.F., Mehta, Z., Rothwell, P.M. Population-based study of delays in carotid imaging and surgery and the risk of recurrent stroke. Neurology. 2005;65(3):371–375.

55. Kastrup, A., et al. Risk factors for early recurrent cerebral ischemia before treatment of symptomatic carotid stenosis. Stroke. 2006;37(12):3032–3034.

56. Harrison, M.J., Marshall, J. Indications for angiography and surgery in carotid artery disease. BMJ. 1975;1(5958):616–618.

57. Harrison, M.J., Marshall, J., Thomas, D.J. Relevance of duration of transient ischaemic attacks in carotid territory. BMJ. 1978;1(6127):1578–1579.

58. Harrison, M.J., Iansek, R., Marshall, J. Clinical identification of TIAs due to carotid stenosis. Stroke. 1986;17(3):391–392.

59. Mast, H., et al. Cigarette smoking as a determinant of high-grade carotid artery stenosis in Hispanic, black, and white patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 1998;29(5):908–912.

60. Voetsch, B., et al. Basilar artery occlusive disease in the New England Medical Center Posterior Circulation Registry. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(4):496–504.

61. West, T.E., Davies, R.J., Kelly, R.E. Horner’s syndrome and headache due to carotid artery disease. BMJ. 1976;1(6013):818–820.

62. Nebelsieck, J., et al. Sensitivity of neurovascular ultrasound for the detection of spontaneous cervical artery dissection. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(1):79–82.

63. Malek, A.M., et al. Endovascular management of extracranial carotid artery dissection achieved using stent angioplasty. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(7):1280–1292.

64. Muller, B.T., et al. Surgical treatment of 50 carotid dissections: Indications and results. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(5):980–988.

65. Homma, S., et al. Effect of medical treatment in stroke patients with patent foramen ovale: Patent foramen ovale in Cryptogenic Stroke Study. Circulation. 2002;105(22):2625–2631.

66. Sacco, R.L., et al. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: Co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Circulation. 2006;113(10):e409–e449.

67. Wassermann, A., Neisser, A., Bruck, C. Eine serodiagnostische Reaction bei Syphilis [German]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1906;32:745–746.

68. The Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Stroke Study (APASS) Group. Anticardiolipin antibodies are an independent risk factor for first ischemic stroke. Neurology. 1993;43(10):2069–2073.

69. Cervera, R., et al. Morbidity and mortality in the antiphospholipid syndrome during a 5-year period: A multicentre prospective study of 1000 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(9):1428–1432.

70. Levine, S.R., et al. Recurrent stroke and thrombo-occlusive events in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1995;38(1):119–124.

71. Lim, W., Crowther, M.A., Eikelboom, J.W. Management of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1050–1057.

72. Adams, H.P., Jr., et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: A guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38(5):1655–1711.

73. Jahromi, A.S., et al. Sensitivity and specificity of color duplex ultrasound measurement in the estimation of internal carotid artery stenosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(6):962–972.

74. Morris, J.G., Duffis, E.J., Fisher, M. Cardiac workup of ischemic stroke: Can we improve our diagnostic yield? Stroke. 2009;40(8):2893–2898.

75. Vivanco Hidalgo, R.M., et al. Cardiac monitoring in stroke units: Importance of diagnosing atrial fibrillation in acute ischemic stroke. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62(5):564–567.

76. Suissa, L., et al. Score for the targeting of atrial fibrillation (STAF): A new approach to the detection of atrial fibrillation in the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(8):2866–2868.

77. Perry, L., Hamilton, S., Williams, J. Formal dysphagia screening protocols prevent pneumonia. Stroke. 2006;37(3):765.

78. Hinchey, J.A., et al. Formal dysphagia screening protocols prevent pneumonia. Stroke. 2005;36(9):1972–1976.

79. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581–1587.

80. Clark, W.M., et al. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (Alteplase) for ischemic stroke 3 to 5 hours after symptom onset. The ATLANTIS Study: A randomized controlled trial. Alteplase Thrombolysis for Acute Noninterventional Therapy in Ischemic Stroke. JAMA. 1999;282(21):2019–2026.

81. Del Zoppo, G.J., et al. Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator: A Science Advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2009;40(8):2945–2948.

82. Hacke, W., et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(13):1317–1329.

83. Wahlgren, N., et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST): An observational study. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):275–282.

84. Smith, W.S., et al. Safety and efficacy of mechanical embolectomy in acute ischemic stroke: Results of the MERCI trial. Stroke. 2005;36(7):1432–1438.

85. Smith, W.S., et al. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: Final results of the Multi MERCI trial. Stroke. 2008;39(4):1205–1212.

86. Groschel, K., et al. A systematic review on outcome after stenting for intracranial atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2009;40(5):e340–e347.

87. IMS II Trial Investigators. The Interventional Management of Stroke (IMS) II Study. Stroke. 2007;38(7):2127–2135.

88. International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. The International Stroke Trial (IST): A randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet. 1997;349(9065):1569–1581.

89. CAST (Chinese Acute Stroke Trial) Collaborative Group. CAST: Randomised placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet. 1997;349(9066):1641–1649.

90. Sandercock, P.A., et al. Antiplatelet therapy for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2008. [CD000029].

91. Gubitz, G., Sandercock, P., Counsell, C. Anticoagulants for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2004. [CD000024].

92. Chandratheva, A., et al. Population-based study of risk and predictors of stroke in the first few hours after a TIA. Neurology. 2009;72(22):1941–1947.

93. Johnston, S.C., et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283–292.

94. Amarenco, P., et al. Does ABCD2 score below 4 allow more time to evaluate patients with a transient ischemic attack? Stroke. 2009;40(9):3091–3095.

95. Bousser, M.G., et al. “AICLA” controlled trial of aspirin and dipyridamole in the secondary prevention of athero-thrombotic cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 1983;14(1):5–14.

96. The Canadian Cooperative Study Group. A randomized trial of aspirin and sulfinpyrazone in threatened stroke. N Engl J Med. 1978;299(2):53–59.

97. Diener, H.C., et al. European Stroke Prevention Study. 2: Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143(1–2):1–13.

98. The ESPS Group. The European Stroke Prevention Study (ESPS). Principal end-points. Lancet. 1987;2(8572):1351–1354.

99. Diener, H.C., et al. Effects of aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel and telmisartan on disability and cognitive function after recurrent stroke in patients with ischaemic stroke in the Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes (PRoFESS) trial: A double-blind, active and placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(10):875–884.

100. CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet. 1996;348(9038):1329–1339.

101. Diener, H.C., et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):331–337.

102. Theis, J.G., Deichsel, G., Marshall, S. Rapid development of tolerance to dipyridamole-associated headaches. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48(5):750–755.

103. Wong, D.K., Lurie, F., Wong, L.L. The effects of clopidogrel on elderly traumatic brain injured patients. J Trauma. 2008;65(6):1303–1308.

104. Sacco, R.L., et al. Comparison of warfarin versus aspirin for the prevention of recurrent stroke or death: Subgroup analyses from the Warfarin-Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;22(1):4–12.

105. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(7):445–453.

106. European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Collaborative Group. MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial: Iinterim results for symptomatic patients with severe (70–99%) or with mild (0–29%) carotid stenosis. Lancet. 1991;337(8752):1235–1243.

107. Chaturvedi, S., et al. Carotid endarterectomy – an evidence-based review: Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2005;65(6):794–801.

108. Liapis, C.D., et al. ESVS guidelines. Invasive treatment for carotid stenosis: Indications, techniques. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37(4 Suppl):1–19.

109. Fode, N.C., et al. Multicenter retrospective review of results and complications of carotid endarterectomy in 1981. Stroke. 1986;17(3):370–376.

110. Brott, T., Thalinger, K. The practice of carotid endarterectomy in a large metropolitan area. Stroke. 1984;15(6):950–955.

111. Gurm, H.S., et al. Long-term results of carotid stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(15):1572–1579.

112. Eckstein, H.H., et al. Results of the Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy (SPACE) study to treat symptomatic stenoses at 2 years: A multinational, prospective, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(10):893–902.

113. Gates, P.C., et al. Symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid stenosis: Just when we thought we had all the answers. Intern Med J. 2006;36(7):445–451.

114. Wacher, K., et al. Carotid endartercectomy deemed safer than stenting. World Neurology. 2010;25(1):15.

115. Meier, P., Knapp, G., Tamhane, V., et al. Short-term and intermediate-term comparison of endarterectomy versus stenting for carotid artery stenosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c467.

116. Norris, J.W., Halliday, A., et al. Carotid artery stenosis: Carotid artery stenting is not yet ready to replace endarterectomy. BMJ. 2010;340:c748.

117. Wijdicks, E.F., et al. The dilemma of discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy for patients with intracranial hemorrhage and mechanical heart valves. Neurosurgery. 1998;42(4):769–773.

118. Ananthasubramaniam, K., et al. How safely and for how long can warfarin therapy be withheld in prosthetic heart valve patients hospitalized with a major hemorrhage? Chest. 2001;119(2):478–484.

119. Bertram, M., et al. Managing the therapeutic dilemma: Patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage and urgent need for anticoagulation. J Neurol. 2000;247(3):209–214.