35 Cerebrovascular disease

Introduction

Cerebral infarcts become swollen after a few days because of osmotic activity. Some become large enough to produce distance effects by causing subfalcal or tentorial herniation of the brain in the manner of a tumor (Ch. 4).

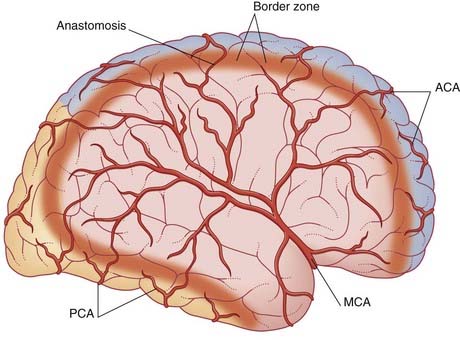

Anterior Circulation of the Brain

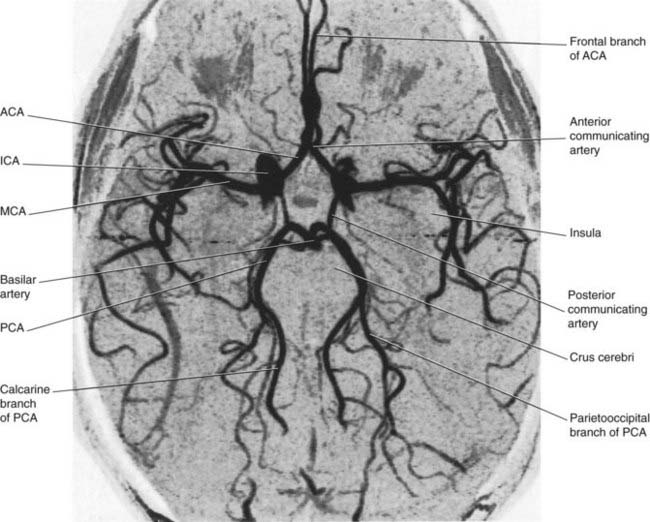

Clinicians refer to the ICA and its branches as the anterior circulation of the brain, and the vertebrobasilar system (including the posterior cerebral arteries) as the posterior circulation. The anterior and posterior circulations are connected by the posterior communicating arteries (Figure 35.2).

Figure 35.2 Circle of Willis and its branches. This is an magnetic resonance (MR) angiogram based on the principle that flowing blood generates a different signal to that of stationary tissue, without injection of a contrast agent. Conventional angiograms, e.g. those in Chapter 5, require arterial perfusion with a contrast agent. The vessels shown here are contained within a single thick MR ‘slice’. Some, e.g. the calcarine branch of the posterior cerebral artery, could be followed further in adjacent slices. ACA, anterior cerebral artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery.

(From a series kindly provided by Professor J. Paul Finn, Director, Magnetic Resonance Research, Department of Radiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, California, USA.)

About 75% of cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) originate in the anterior circulation.

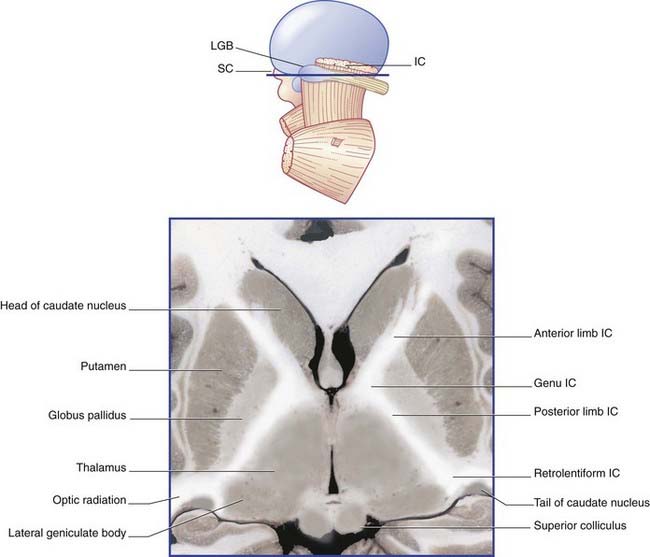

Internal capsule

The following details supplement the account of the arterial supply of the internal capsule in Chapter 5.

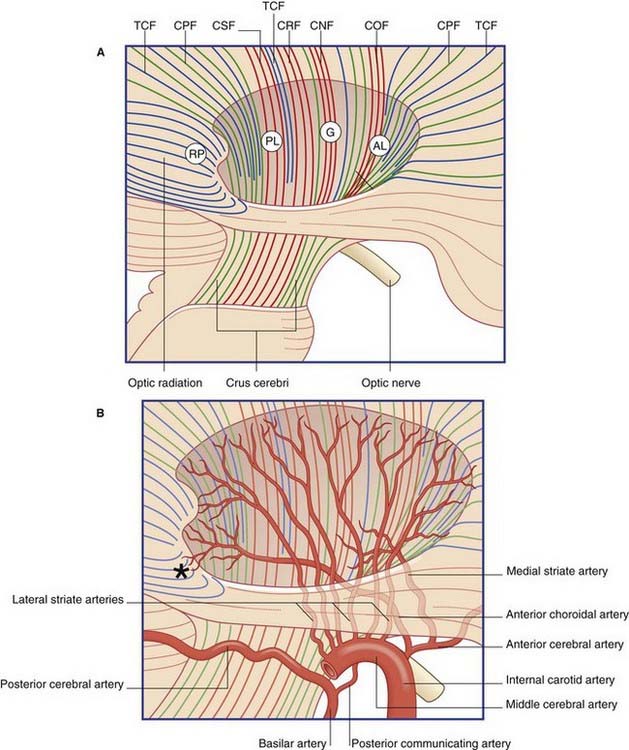

The blood supply of the internal capsule is shown in Figure 35.3. The three sources of supply are the anterior choroidal, a direct branch of the internal carotid; the medial striate, a branch of the anterior cerebral, and lateral striate (lenticulostriate) branches of the middle cerebral artery.

Figure 35.3 Internal capsule.

(A) Pathways. Lateral view of the right cerebral hemisphere, showing the oval depression in the white matter following removal of the lentiform nucleus. The internal capsule occupies the floor of the depression. CNF, corticonuclear fibers; COF, cortico-oculomotor fibers; CPF, corticopontine fibers; CRF, corticoreticular fibers; CSF, corticospinal fibers; TCF, thalamocortical fibers. Other abbreviations as in Figure 35.4.

The contents of the internal capsule are shown in Figure 35.4. The anterior choroidal branch of the internal carotid artery supplies the lower part of the posterior limb and the retrolentiform part of the internal capsule, and the inferolateral part of the lateral geniculate body. Some of its branches (not shown) supply a variable amount of the temporal lobe of the brain and the choroid plexus of the inferior horn of the lateral ventricle.

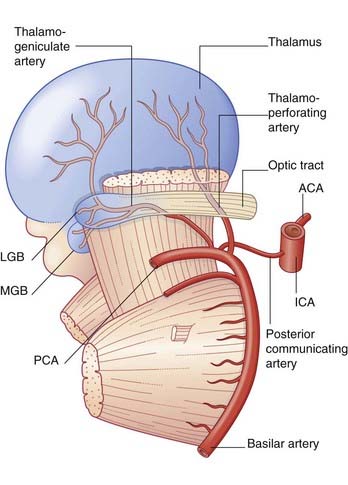

Posterior Circulation of the Brain

Additional information is confined to the stem branches of the posterior cerebral artery shown in Figure 35.5.

Transient Ischemic Attacks

Clinical Anatomy of Vascular Occlusions

In the Clinical Panels, the term occlusion encompasses all causes of regional arterial failure other than aneurysms. Symptoms of occlusions within the anterior circulation are summarized in Clinical Panels 35.1–35.4, within the posterior circulation in Clinical Panel 35.5, specifically within the terrirory of the posterior cerebral artery in Clinical Panel 35.6. Subarachnoid hemmorrhage is considered in Clinical Panel 35.7.

Clinical Panel 35.1 Anterior choroidal artery occlusion

A complete anterior choroidal artery syndrome is produced by occlusion of the proximal part of the artery, compromising the lower part of the posterior limb and retrolentiform part of the internal capsule. The clinical picture is one of contralateral hemiparesis, hemisensory loss of cortical type (Ch. 29), and hemianopia. Damage to the (crossed) cerebellothalamocortical pathway may add evidence of intention tremor in the contralateral upper limb, yielding so-called ataxic hemiparesis.

Clinical Panel 35.2 Anterior cerebral artery occlusion

Clinical Panel 35.3 Middle cerebral artery occlusion

Embolism

Stem

The condition of some patients with stem occlusion improves markedly within days, as explained in Clinical Panel 35.8.

Lower division

Embolism of the lower division produces contralateral homonymous hemianopia, and sometimes a confused, agitated state attributed to involvement of limbic pathways in the temporal lobe. Left-sided lesions are also accompanied by Wernicke’s aphasia, alexia, and sometimes by ideomotor apraxia (corresponding to lesion 3 in Figure 32.7).

Lacunar infarcts

Hemorrhage

A typical clinical case is one in which a sudden, severe headache is followed by unconsciousness within a few minutes. The eyes tend to drift toward the side of the lesion, as noted in Chapter 29. With recovery of consciousness, there is a complete, flaccid hemiplegia (apart from the upper part of the face). Tendon reflexes are absent on the hemiplegic side and a Babinski sign is present.

The end result of capsular stroke is often one of ambulatory spastic hemiparesis with hemihypesthesia (reduced sensation). Figure CP 35.3.1 shows the typical posture during walking: the elbow and fingers are flexed and the leg has to be circumducted during the swing phase (unless an ankle brace is worn) because of the antigravity tone of the musculature. During the early rehabilitation period an arm sling is required in order to protect the shoulder joint from downward subluxation (partial dislocation) This is because the supraspinatus muscle is normally in continuous contraction when the body is upright, preventing slippage of the humeral head.

Figure CP 35.3.2 is from a magnetic resonance (MR) study of a patient who had suffered a right hemiplegia with sensory loss 11 days previously. The picture shows extensive infarction of the white matter on the left side, at the junctional region between the corona radiata and internal capsule, with compression of the lateral ventricle.

Figure CP 35.3.2 Contrast-enhanced MR image taken from a patient 11 days after an embolic stroke (see text).

(From Sato A et al, Radiology 178:433–439, 1991, with kind permission of Dr S. Takahashi, Department of Radiology, Tohoku University School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan, and the editors of Radiology.)

Clinical Panel 35.5 Occlusions within the posterior circulation

Small brainstem infarcts may yield the following features:

The posterior cerebral arteries are usually perfused through the basilar bifurcation. Occlusion is more common in branches than in either main stem (Clinical Panel 35.6).

Clinical Panel 35.6 Posterior cerebral artery occlusion

Thalamus

Occlusion of a thalamogeniculate branch may cause infarction of the posterior lateral nucleus of the thalamus (which receives the spinothalamic tract and medial lemniscus), and sometimes of the lateral geniculate nucleus also. The usual result is a contralateral sense of numbness, perhaps with hemianopia. The rare and unpleasant thalamic syndrome (Ch. 27) may supervene.

Subthalamic nucleus

Occlusion of a thalamoperforating branch may destroy the small subthalamic nucleus and give rise to ballism on the contralateral side, usually affecting the arm (Ch. 33).

Clinical Panel 35.7 Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Blister-like ‘berry’ aneurysms 5–10 mm in diameter are a routine autopsy finding in about 5% of people. Most are in the anterior half of the circle of Willis. Spontaneous rupture of an aneurysm into the interpeduncular cistern usually occurs in early or late middle age. The characteristic presentation is a sudden blinding headache, with collapse into semiconsciousness or coma within a few seconds. On physical examination, a diagnostic feature (absent in one-third of cases) is nuchal (neck) rigidity. This is caused by movement of blood into the posterior cranial fossa, where the dura mater is supplied by cervical nerves 2 and 3 (Ch. 4). The term meningismus is sometimes used for this sign.

Finally, recovery of motor function after a stroke is discussed in Clinical Panel 35.8.

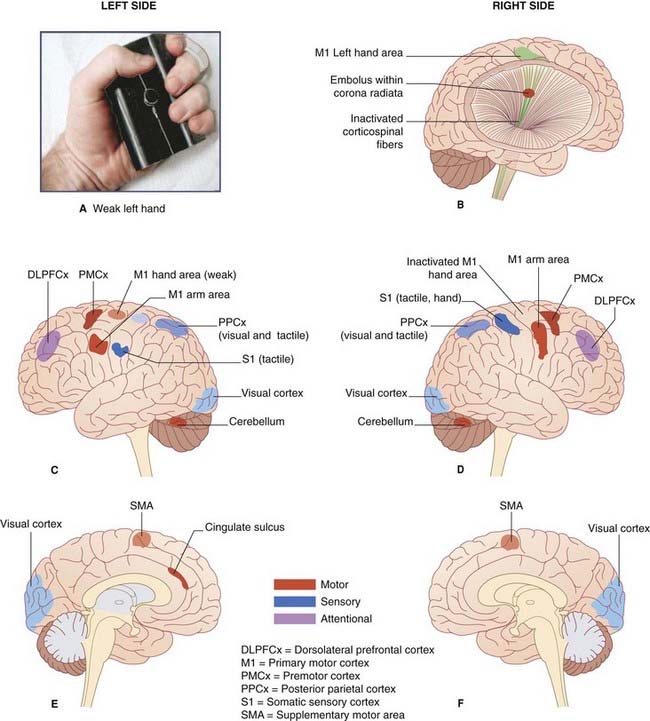

Clinical Panel 35.8 Motor recovery after stroke

Very early recovery – up to 24 hours

Later recovery

Reorganization within the affected M1

Contributions originating outside the affected M1

Brozici M, van der Zwan A, Hillen B. Anatomy and functionality of leptomeningeal anastomoses: a review. Stroke. 2003;34:2750-2758.

Cramer SC. Repairing the human brain after stroke: I. Mechanisms of spontaneous recovery. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:272-287. II. Restorative therapies, Ann Neurol 63:549–560, 2008

Giles MF, Rothwell PM. Transient ischaemic attack: clinical revelance, risk prediction and urgency of secondary prevention. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22:46-53.

Henry JL, Lalloo C, Yashpal K. Central poststroke pain: an abstruce outcome. Pain Res Manage. 2008;13:41-49.

Losseff L, Browne M, Grieve J. Stroke and cerebrovascular disease. In: Clarke C, Howard R, Rossor M, Shorvon S, editors. Queen Square Textbook of Neurology. London: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009:109-154.

Schaechter JD. Motor rehabilitation and brain plasticity after hemiparetic stroke. Progr Neurobiol. 2004;73:61-72.

Ward NS, Brown MM, Thompson AJ, Frockowiak RSJ. Neural correlates of motor recovery after stroke. Brain. 2003;126:2476-2496.

Ward NS, Cohen LG. Mechanisms underlying recovery of motor function after stroke. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1844-1848.

(A) The ‘manipulandum’ used by Ward et al. to register the squeezing power of the affected hand.

(B) Depiction of embolic compromise of the right corticospinal tract.

(D) Corresponding view of the right (lesional) side.

(E) Medial view of the left side.

(F) Medial view of the right side.

(Assistance of Dr. Nick Ward, Honorary Consultant Neurologist, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London is gratefully acknowledged.)

Core Information

Arterial occlusion within the anterior circulation

Clinical effects of anterior, middle and posterior cerebral artery branch occlusion are summarized in Tables 35.1–35.4.

Table 35.1 Clinical effects of anterior cerebral artery branch occlusion

| Branch | Clinical effects |

|---|---|

| Orbital/frontopolar | Apathy with some memory loss |

| Medial striate | Paresis of face and arm |

| Callosomarginal | Paresis and hypesthesia of face and arm ± abulia ± mutism ± inability to reach across |

| Pericallosal | Ideomotor apraxia (anterior lesion), tactile anomia (posterior lesion) |

Table 35.2 Clinical effects of middle cerebral artery occlusion

| Segment | Clinical effects |

| Left temporal | Wernicke aphasia |

| Either stem | Hemiplegia, hemihypesthesia, hemianopia |

| Left stem | Same + global aphasia |

| Right stem | Same + sensory neglect |

| Either upper division | Paresis and hypesthesia of face and arm, dysarthria |

| Left upper division | Same + Broca’s aphasia |

| Right upper division | Same + hemineglect or expressive aprosodia |

| Either lower division | Hemianopia ± agitated state |

| Left lower division | Same ± Wernicke’s aphasia, alexia, ideomotor apraxia |

| Branches | |

|---|---|

| Orbitofrontal | Prefrontal syndrome |

| Left precentral | Broca’s aphasia |

| Right precentral | Motor aprosodia |

| Central | Loss of motor ± sensory function in face and arm |

| Inferior parietal | Hemineglect |

| Either angular | Hemianopia |

| Left angular | Alexia |

| Right temporal | Receptive aprosodia |

Table 35.3 Clinical effects of three common lacunar infarcts

| Location | Clinical effects |

|---|---|

| Genu of internal capsule | Dysarthria-clumsy hand syndrome ± dysphagia |

| Posterior limb of internal capsule | Pure motor hemiparesis |

| Ventral posterior nucleus of thalamus | Pure sensory syndrome ± sensory ataxia |

Table 35.4 Clinical effects of posterior cerebral artery occlusion

| Stem | Clinical effects |

|---|---|

| Either | Homonymous hemianopia |

| Left | Alexia in visible field |

| Both | Cortical blindness ± amnesia |

| Branch | |

|---|---|

| Midbrain | Ipsilateral third nerve palsy + contralateral hemiplegia |

| Thalamus | Contralateral numbness ± hemianopia ± thalamic syndrome |

| Subthalamic nucleus | Contralateral ballism |

| Corpus callosum | Alexia in contralateral visual field |

The effects of middle cerebral artery occlusion are shown in Table 35.2.

Small lacunar infarcts are commonly associated with chronic hypertension. Typical examples are in Table 35.3.

Clinical effects of vertebrobasilar arterial occlusion have been summarized in the main text.

De Ruck J, de Groote L, Van Maele G. The classic lacunar syndromes: clinical and neuroimaging correlates. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:681-684.

Lee JS, Han M-K, Kim SH, Kwon H-K, Kim JH. Fiber tracking by diffusion tensor imaging in corticospinal tract stroke: topographical correlation with clinical symptoms. Neuroimage. 2005;26:771-776.

Losseff N, Brown M, Grieve J. Stroke and cerebrovascular diseases. In: Clarke C, Howard R, Rossor M, Shorvon S, editors. Neurology: A Queen Square Textbook. London: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009:109-194.

Wardlaw JM. What causes lacunar stroke? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:617-619.