2 Cerebral topography

Surface Features

Lobes

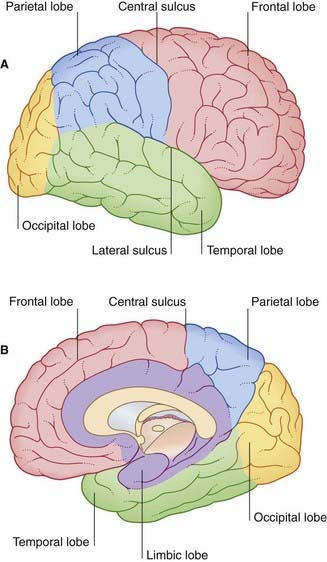

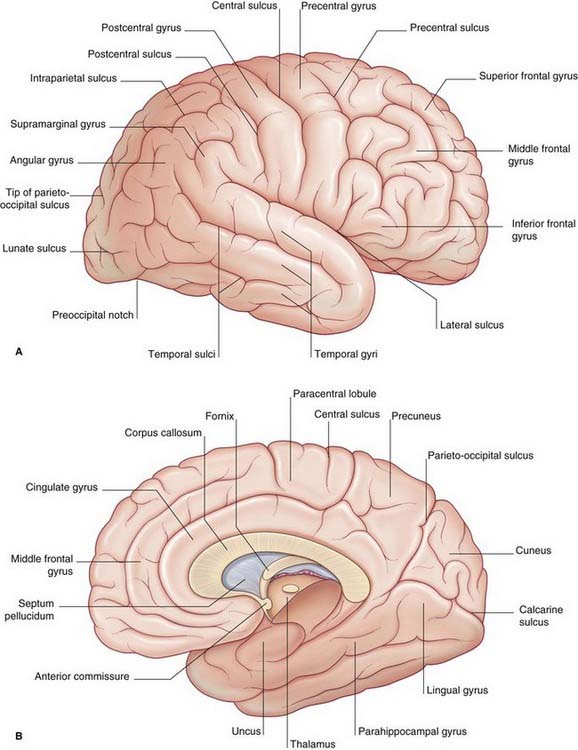

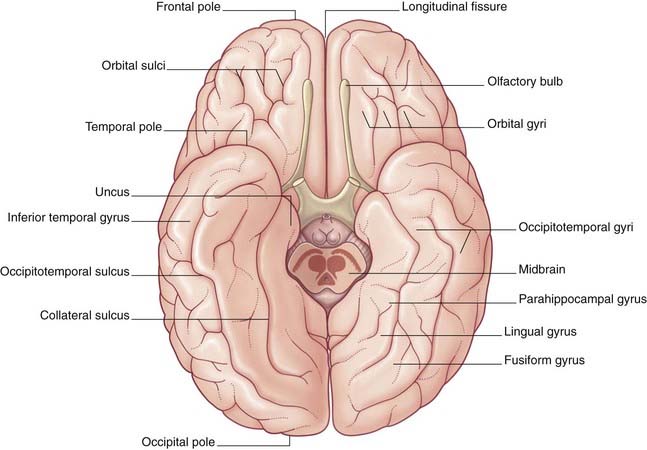

The surfaces of the two cerebral hemispheres are furrowed by sulci, the intervening ridges being called gyri. Most of the cerebral cortex is concealed from view in the walls of the sulci. Although the patterns of the various sulci vary from brain to brain, some are sufficiently constant to serve as descriptive landmarks. Deepest sulci are the lateral sulcus (Sylvian fissure) and the central sulcus (Rolandic fissure) (Figure 2.1A). These two serve to divide the hemisphere (side view) into four lobes, with the aid of two imaginary lines, one extending back from the lateral sulcus, the other reaching from the upper end of the parietooccipital sulcus (Figure 2.1B) to a blunt preoccipital notch at the lower border of the hemisphere (the sulcus and notch are labeled in Figure 2.3). The lobes are called frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal.

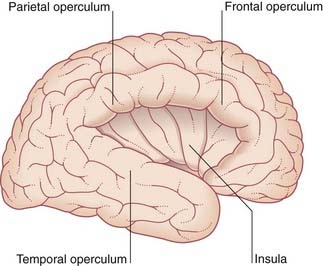

The opercula (lips) of the lateral sulcus can be pulled apart to expose the insula (Figure 2.2). The insula was mentioned in Chapter 1 as being relatively quiescent during prenatal expansion of the telencephalon.

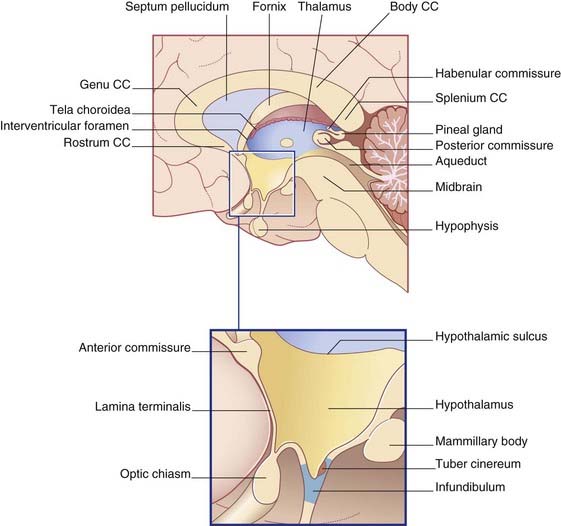

The medial surface of the hemisphere is exposed by cutting the corpus callosum, a massive band of white matter connecting matching areas of the cortex of the two hemispheres. The corpus callosum consists of a main part or trunk, a posterior end or splenium, an anterior end or genu (‘knee’), and a narrow rostrum reaching from the genu to the anterior commissure (Figure 2.3B). The frontal lobe lies anterior to a line drawn from the upper end of the central sulcus to the trunk of the corpus callosum (Figure 2.3B). The parietal lobe lies behind this line, and it is separated from the occipital lobe by the parietooccipital sulcus. The temporal lobe lies in front of a line drawn from the preoccipital notch to the splenium.

Figures 2.3–2.6 should be consulted along with the following description of surface features of the lobes of the brain.

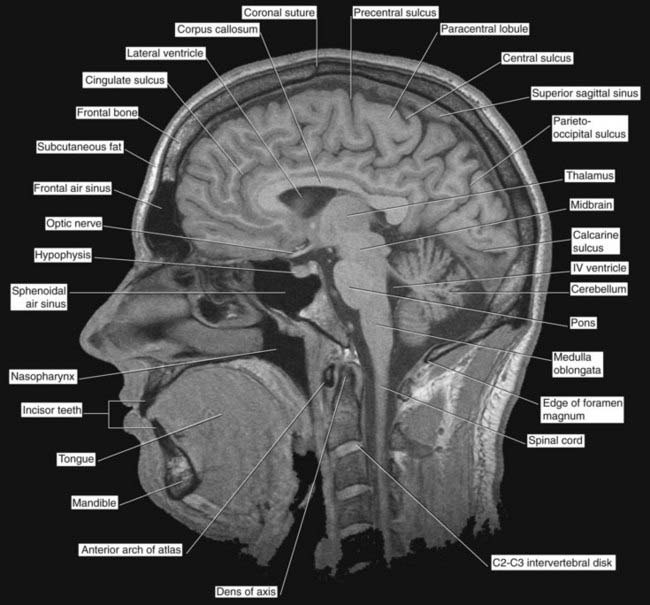

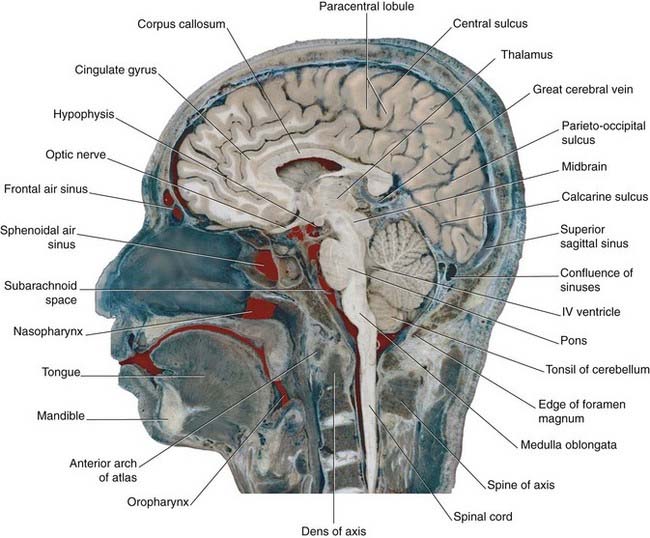

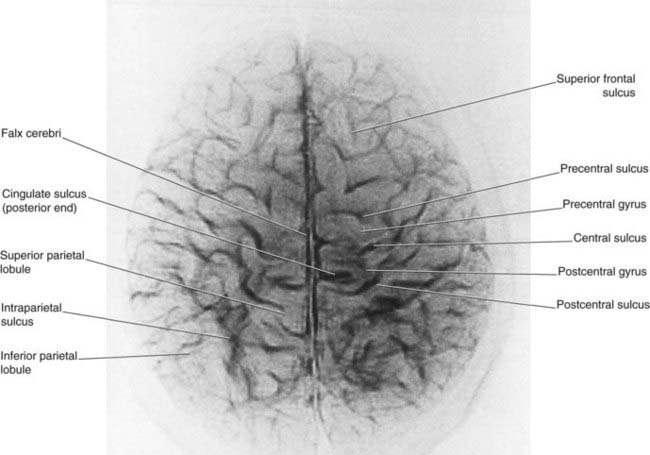

Figure 2.4 ’Thick slice’ surface anatomy brain MRI scan from a healthy volunteer.

(From Katada, 1990.)

Limbic lobe

A fifth, limbic lobe of the brain surrounds the medial margin of the hemisphere. Surface contributors to the limbic lobe include the cingulate and parahippocampal gyri. It is more usual to speak of the limbic system, which includes the hippocampus, fornix, amygdala, and other elements (Ch. 34).

Diencephalon

The largest components of the diencephalon are the thalamus and the hypothalamus (Figures 2.6 and 2.7). These nuclear groups form the side walls of the third ventricle. Between them is a shallow hypothalamic sulcus, which represents the rostral limit of the embryonic sulcus limitans.

Internal Anatomy ofthe Cerebrum

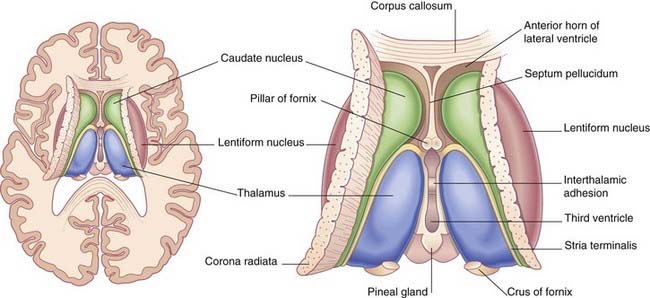

Thalamus, caudate and lentiform nuclei, internal capsule

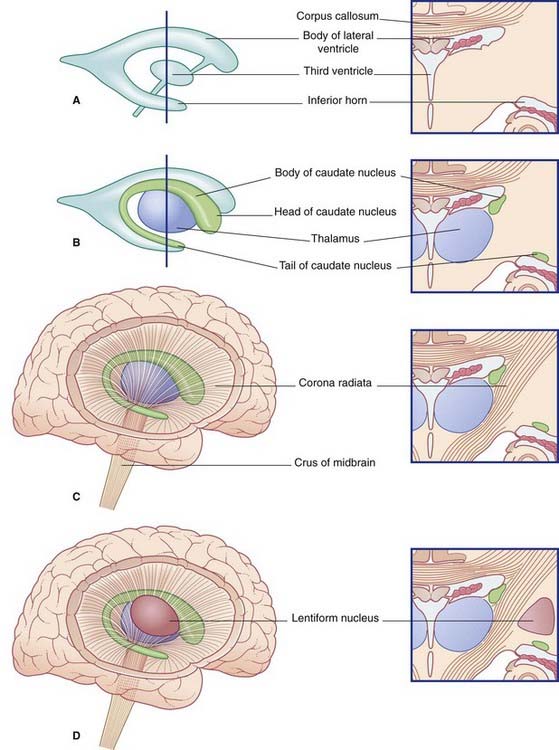

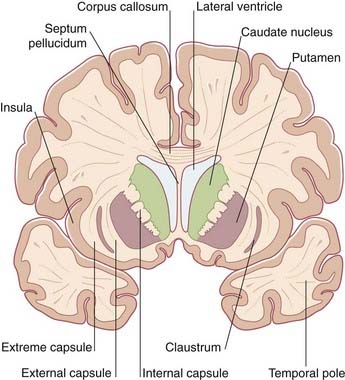

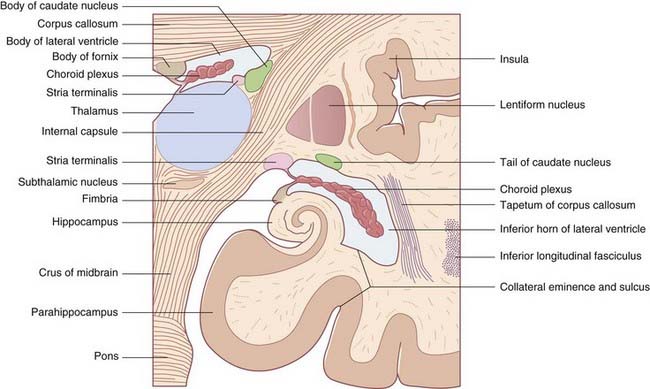

The two thalami face one another across the slot-like third ventricle. More often than not, they kiss, creating an interthalamic adhesion (Figure 2.9). In Figure 2.10, the thalamus and related structures are assembled in a mediolateral sequence. In contact with the upper surface of the thalamus are the head and body of the caudate nucleus. The tail of the caudate nucleus passes forward below the thalamus but not in contact with it.

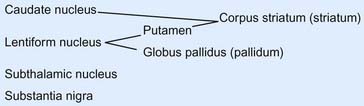

The caudate and lentiform nuclei belong to the basal ganglia, a term originally applied to a half-dozen masses of gray matter located near the base of the hemisphere. In current usage, the term designates four nuclei known to be involved in motor control: the caudate and lentiform nuclei, the subthalamic nucleus in the diencephalon, and the substantia nigra in the midbrain (Figure 2.11).

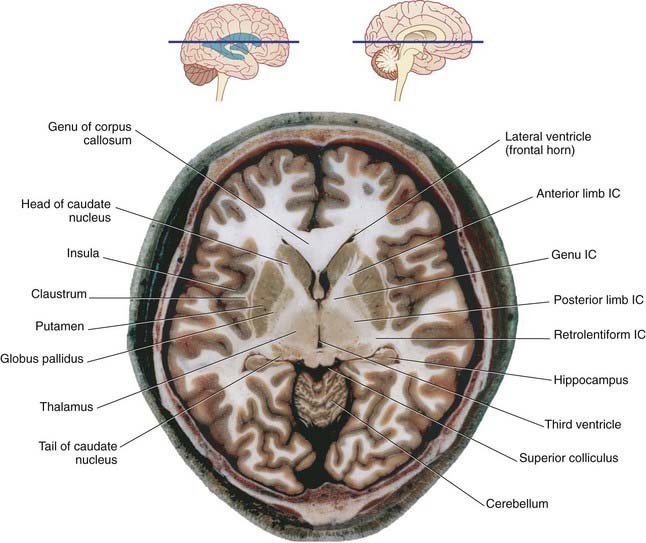

In horizontal section, the internal capsule has a dog-leg shape (see photograph of a fixed-brain section in Figure 2.12, and the living-brain magnetic resonance image [MRI] ‘slice’ in Figure 2.13). The internal capsule has four named parts in horizontal sections:

Figure 2.12 Horizontal section of fixed cadaver brain at the level indicated at top. IC, internal capsule.

(From Liu et al. 2003, with permission of Shantung Press of Science and Technology.)

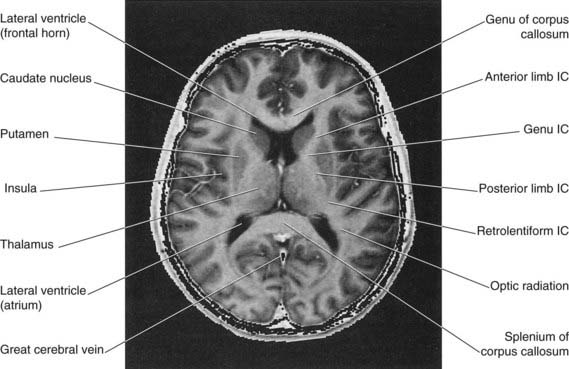

Figure 2.13 Horizontal MRI ‘slice’ in the plane of Figure 2.12. IC, internal capsule.

(From a series kindly provided by Professor J. Paul Finn, Director, Magnetic Resonance Research, Department of Radiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, California, USA.)

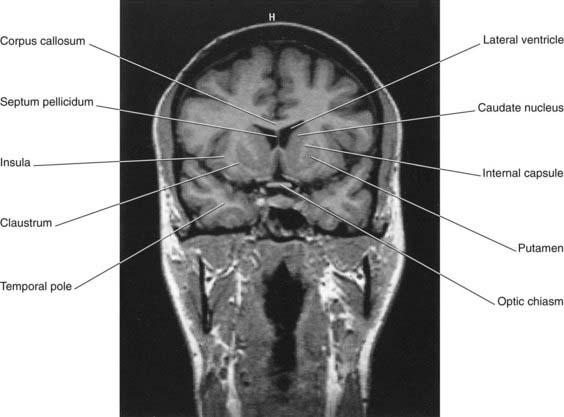

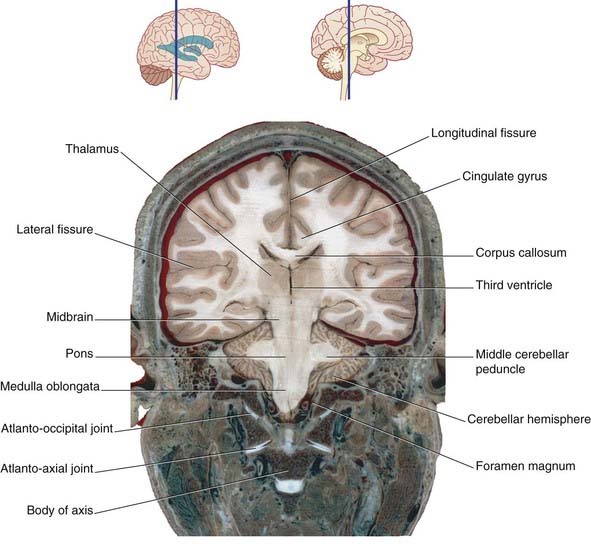

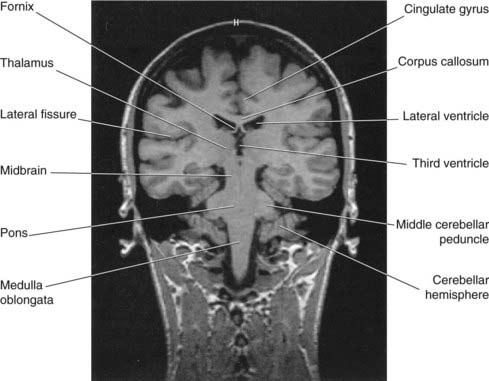

A coronal section through the anterior limb is represented in Figure 2.14; a corresponding MRI view is shown in Figure 2.15. A coronal section through the posterior limb from a fixed brain is shown in Figure 2.16; a corresponding MRI slice is shown in Figure 2.17.

Figure 2.15 Coronal MRI ‘slice’ at the level of Figure 2.14.

(From a series kindly provided by Professor J. Paul Finn, Director, Magnetic Resonance Research, Department of Radiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, California, USA.)

Figure 2.16 Coronal section of fixed cadaver brain at the level indicated at top.

(From Liu et al. 2003, with permission of Shantung Press of Science and Technology.)

Figure 2.17 Coronal MRI ‘slice’ at the level of Figure 2.16.

(From a series kindly provided by Professor J. Paul Finn, Director, Magnetic Resonance Research, Department of Radiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, California, USA).

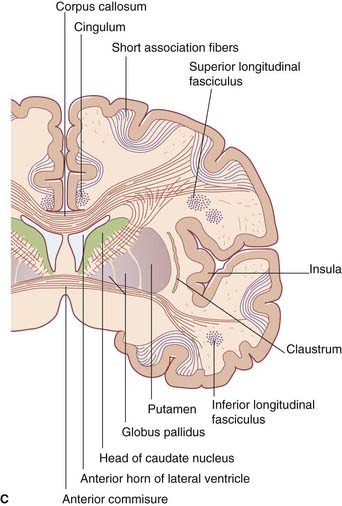

Lateral to the lentiform nucleus are the external capsule, claustrum, and extreme capsule.

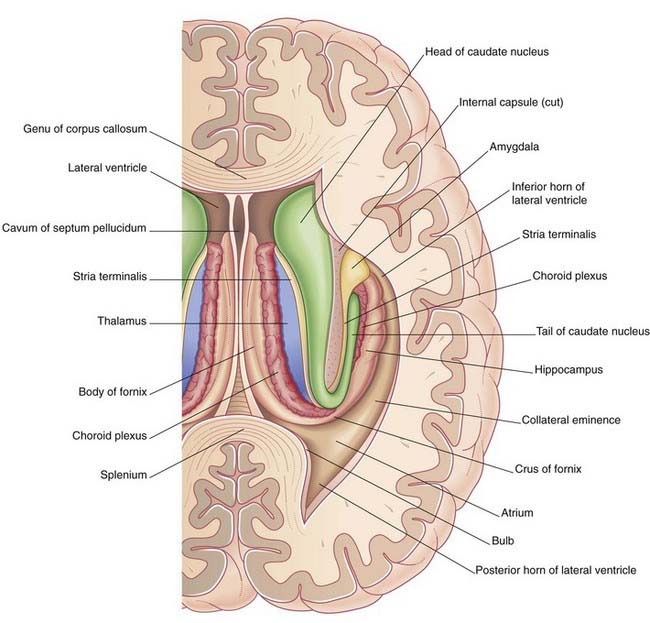

Hippocampus and fornix

During embryonic life, the hippocampus (crucial for memory formation) is first seen above the corpus callosum. The bulk of it remains in that position in lower mammals. In primates, it retreats into the temporal lobe as this lobe develops, leaving a tract of white matter, the fornix, in its wake. The mature hippocampus stretches the full length of the floor of the inferior (temporal) horn of the lateral ventricle (Figures 2.18 and 2.19). The mature fornix comprises a body beneath the trunk of the corpus callosum, a crus, which enters it from each hippocampus, and two pillars (columns), which leave it to enter the diencephalon. Intimately related to the crus and body is the choroid fissure, through which the choroid plexus is inserted into the lateral ventricle.

Association and commissural fibers

Fibers leaving the cerebral cortex fall into three groups:

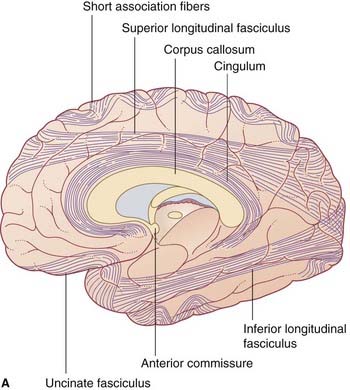

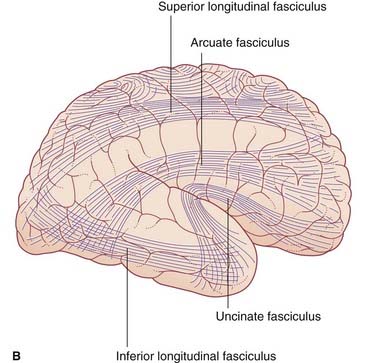

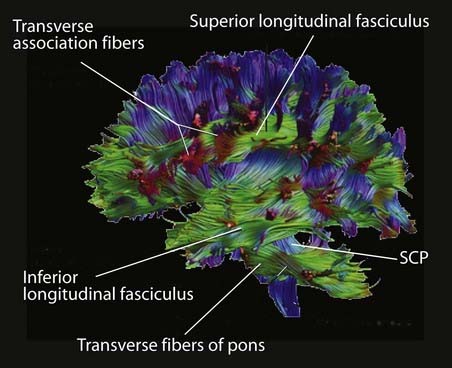

Association fibers (Figure 2.20)

Short association fibers pass from one gyrus to another within a lobe.

Long association fibers link one lobe with another. Bundles of long association fibers include:

Cerebral commissures

Corpus callosum

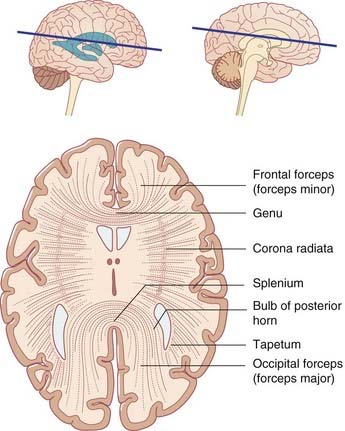

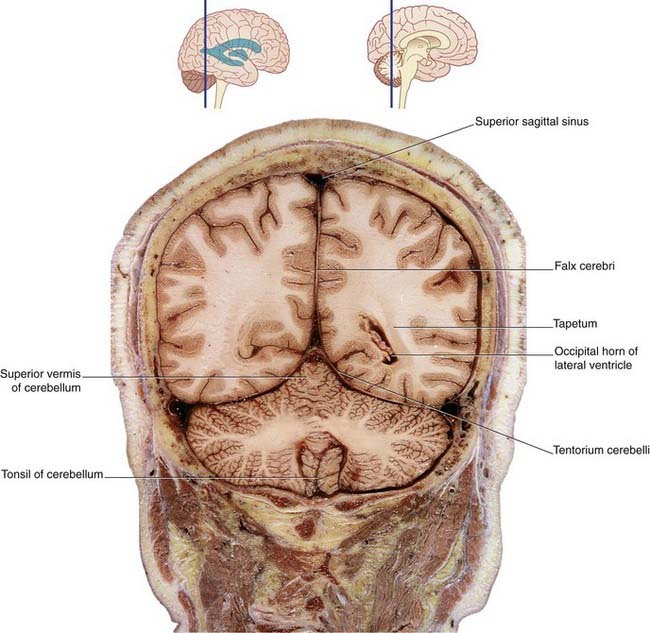

The corpus callosum is the largest of the commissures linking matching areas of the left and right cerebral cortex (Figure 2.21). From the body, some fibers pass laterally and upward, intersecting the corona radiata. Other fibers pass laterally and then bend downward as the tapetum to reach the lower parts of the temporal and occipital lobes. Fibers traveling to the medial wall of the occipital lobe emerge from the splenium on each side and form the occipital (major) forceps. The frontal (minor) forceps emerges from each side of the genu to reach the medial wall of the frontal lobe.

Lateral and third ventricles

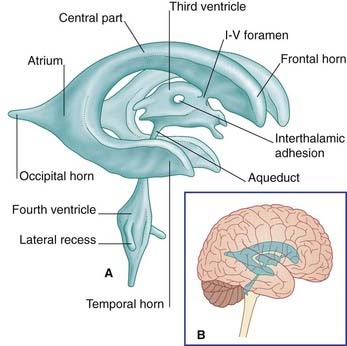

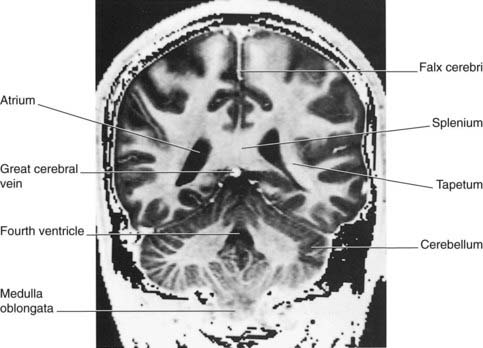

The lateral ventricle consists of a body within the parietal lobe, and anterior (frontal), posterior (occipital), and inferior (temporal) horns (Figure 2.22). The anterior limit of the central part is the interventricular foramen, located between the thalamus and anterior pillar of the fornix, through which it communicates with the third ventricle. The central part joins the occipital and temporal horns at the atrium (Figures 2.23 and 2.24).

Figure 2.23 Coronal section of fixed cadaver brain at the level indicated at top.

(From Liu et al. 2003, with permission of Shantung Press of Science and Technology.)

Figure 2.24 Coronal MRI ‘slice’ at the level indicated at top.

(From a series kindly provided by Professor J. Paul Finn, Director, Magnetic Resonance Research, Department of Radiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, California, USA.)

The relationships of the lateral ventricle are listed below.

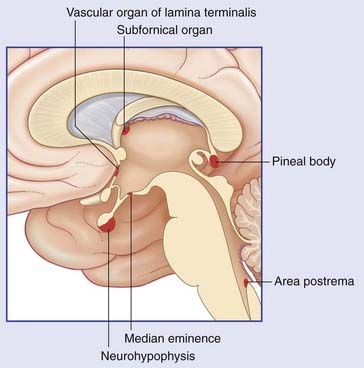

The third ventricle is the cavity of the diencephalon. Its boundaries are shown in Figure 2.6. A choroid plexus hangs from its roof, which is formed of a double layer of pia mater called the tela choroidea. Above this are the fornix and corpus callosum. In the side walls are the thalamus and hypothalamus. The anterior wall is formed by the anterior commissure, the lamina terminalis, and the optic chiasm. In the floor are the infundibulum, the tuber cinereum, the mammillary bodies (also spelt ‘mamillary’), and the upper end of the midbrain. The pineal gland and adjacent commissures form the posterior wall. The pineal gland is often calcified, and the habenular commissure is sometimes calcified, as early as the second decade of life, thereby becoming detectable even on plain radiographs of the skull. The pineal gland is sometimes displaced to one side by a tumor, hematoma, or other mass (space-occupying lesion) within the cranial cavity.

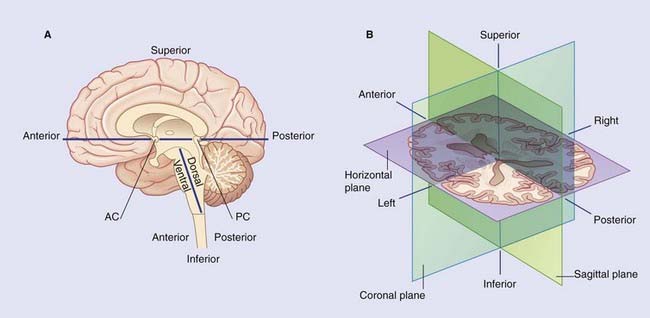

Box 2.1 Brain planes

Box 2.2 Magnetic resonance imaging

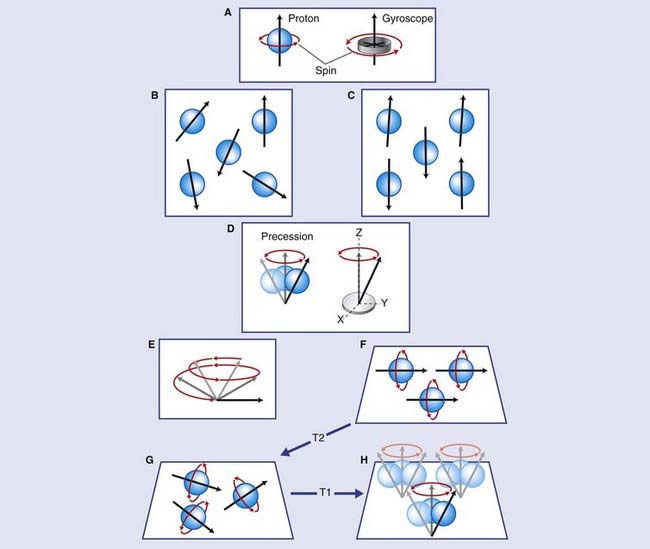

Nuclei possess a property known as spin (Figure Box 2.2.1), and it may be helpful to visualize this as akin to a spinning gyroscope. Normally, the direction of the spin (the axis of the gyroscope in our analogy) for any given nucleus is random. Spin produces a magnetic moment (vector) that makes it behave like a tiny dipole (north and south) magnet. In the absence of any external magnetic field, the dipoles are randomly arranged.

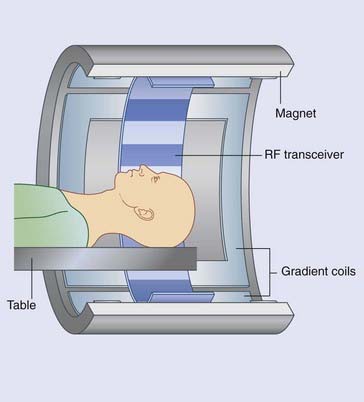

The cylindric external magnet of an MRI machine (Figure Box 2.2.2) is immensely powerful, capable of lifting the weight of several cars at one time. When the magnet is switched on, individual nuclear magnetic moments undergo a process called – precession analogous to the wobbling of a gyroscope – whereby they adopt a cone-shaped spin around the z axis of the external magnetic field.

Figure Box 2.2.2 The MRI machine. Outermost is the magnet. Innermost is the radio-frequency transceiver. In between are the gradient coils.

The varying densities within the magnetic resonance images reflect the varying rates of dephasing and of relaxation of protons in different locations. The protons of the cerebrospinal fluid, for example, are free to resonate at maximum frequency, whereas in the white matter they are largely bound to lipid molecules. The gray matter has intermediate values, some protons being protein-bound. The radio-frequency pulses can be varied to exploit these differences. Almost all the images shown in textbooks (including this one) are T1-weighted, favoring the very weak signal provided by free protons during the relaxation period. This accounts for the different densities of CSF, gray matter, and white matter, the last being strongest. The reverse is true for T2-weighted images. T2-weighted images are especially useful in detection of lesions in the white matter. For example, they can indicate an increase in free protons resulting from patchy loss of myelin sheath lipid in multiple sclerosis (see Ch. 6), or local edema of brain tissue resulting from a vascular stroke.

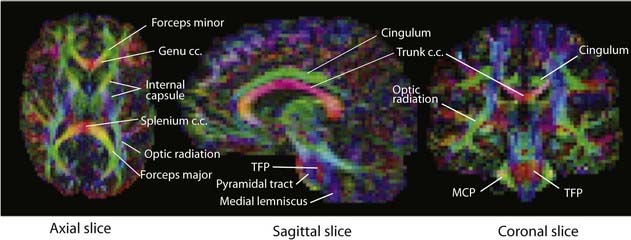

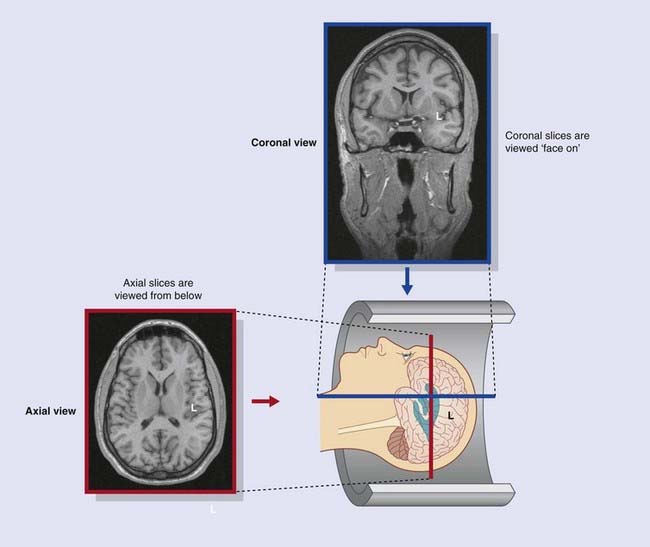

The standard orientation of coronal and axial slices is shown in Figure Box 2.2.3.

Figure Box 2.2.3 Standard orientation of magnetic resonance images. Coronal sections are viewed from in front. Axial sections are viewed from below.

Jones DK. Fundamentals of diffusion MRI imaging. In: Gillard JH, Waldman AD, Barker PB, editors. Fundamentals of neuroimaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005:54-85.

Mitchell DG, Cohen MS. MRI principles, ed 3. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.

Saper CB, Iversen S, Frackoviak R, Kandel ER, Schwarz JH, Jessell TJ, editors. Principles of neural science, ed 4. New York 2000,, McGraw-Hill, pp 370-375.

Box 2.3 Diffusion tensor imaging

Terms

Clarke C, Howard R. Nervous system structure and function. In: Clarke C, Howard R, Rossor M, Shorvon S, editors. Neurology: A Queen Square Textbook. London: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009:13-74.

England MA, Wakely J. A colour atlas of the brain and spinal cord. St. Louis: Mosby; 2005.

Katada K. MR imaging of brain surface structures: surface anatomy scanning (SAS). Neuroradiology. 1990;3(5):439-448.

Kretschmann H-J, Weinrich W. Cranial neuroimaging and clinical neuroanatomy. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1998.

Liu S, et al, editors: Atlas of human sectional anatomy. Jinan, 2003, Shantung Press of Science and Technology.