42 Caudal Block

Placement

Anatomy

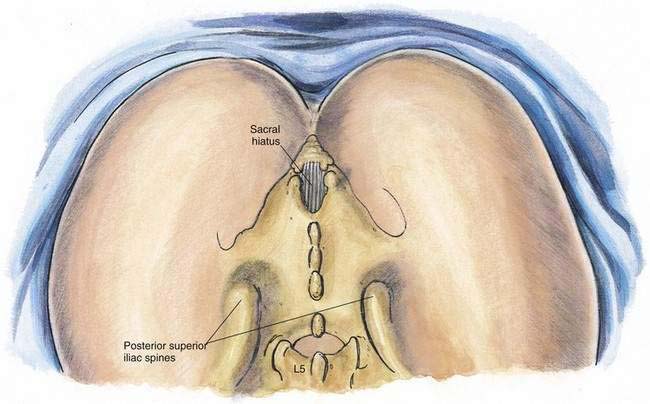

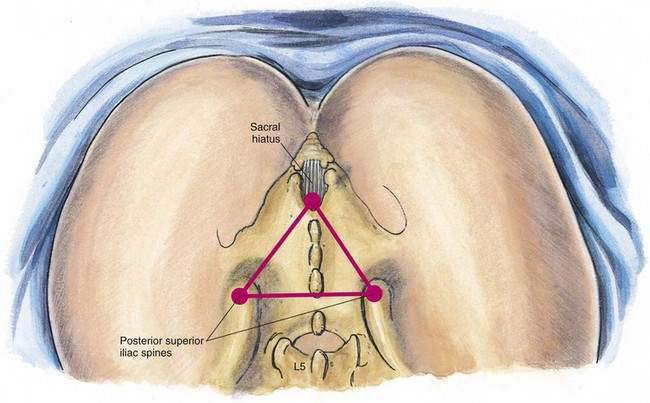

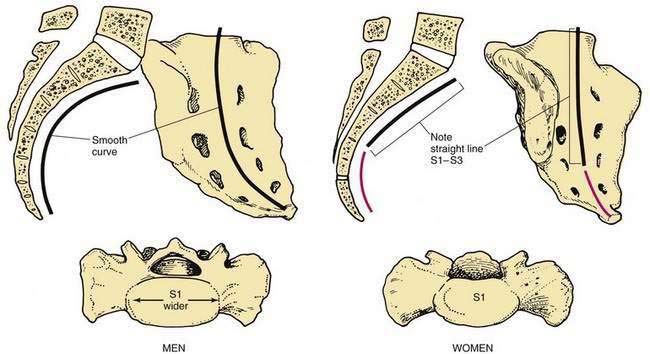

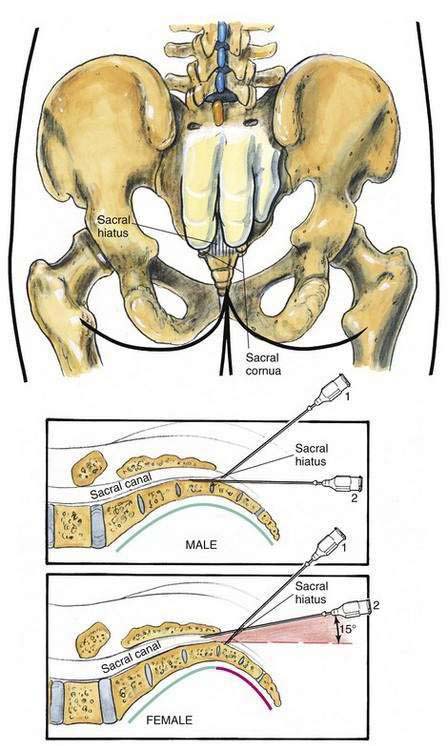

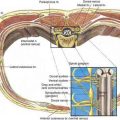

Anatomy pertinent to caudal anesthesia centers on the sacral hiatus (Fig. 42-1). This can be most effectively localized by finding the posterior superior iliac spines bilaterally, drawing a line to join them, and then completing an equilateral triangle caudad. The tip of the equilateral triangle will overlie the sacral hiatus (Fig. 42-2). The caudal tip of the triangle will rest near the sacral cornua, which are unfused remnants of the spinous processes of the fifth sacral vertebra. Overlying the sacral hiatus is a fibroelastic membrane, which is the functional counterpart of the ligamentum flavum. Perhaps more than with any other sex difference found in regional anesthesia, the sacrum is distinctly different in men and women. In men, the cavity of the sacrum has a smooth curve from S1 to S5. Conversely, in women the sacrum is quite flat from S1 to S3, with a more pronounced curve in the S4 to S5 region (Fig. 42-3).

Position

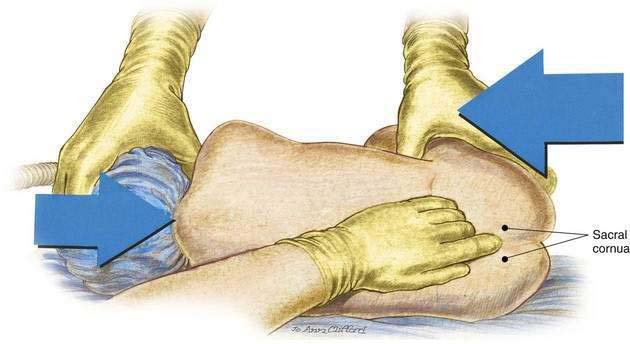

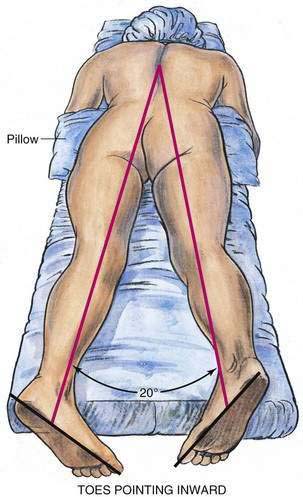

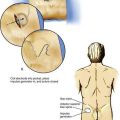

Caudal block can be carried out in a lateral decubitus position or a prone position. In adults, I find the prone position with a pillow placed beneath the lower abdomen most effective. In this position, patients can be sufficiently sedated to make the block comfortable, and it makes the midline more easily identifiable than in the lateral position. As illustrated in Figure 42-4, pediatric caudal anesthesia is commonly carried out with the child in the lateral decubitus position. Because most pediatric caudal blocks are performed after induction with general anesthesia, the lateral position is almost mandatory. Identification of the midline and performance of the block are less complicated in the pediatric patient, thus making the lateral position clinically practical. To optimize identification of the sacral hiatus, the prone patient should have the legs abducted to a 20-degree angle with the toes rotated inward and the heels outward. This helps relax the gluteal muscles, making it easier to identify the sacral hiatus (Fig. 42-5).

Needle Puncture

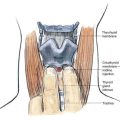

As with lumbar epidural anesthesia, caudal anesthesia requires a decision about the use of a single-injection or a catheter technique. If a single-shot caudal block is to be performed, almost any needle of sufficient length to reach the caudal canal is acceptable. In adults, a needle of at least 22 gauge is recommended because it is large enough to allow sufficiently rapid injection of solution to help detect misplaced local anesthetic injections. If a catheter is to be used, a needle that is large enough to allow passage of the catheter is required. As illustrated in Figure 42-6, after the sacral hiatus is identified, the index and middle fingers of the palpating hand are each placed on the sacral cornua, and the caudal needle is inserted at an angle of approximately 45 degrees to the sacrum. As the anesthesiologist advances the needle, he or she will become aware of a decrease in resistance as the needle enters the caudal canal (needle position 1). The needle is then advanced until it contacts bone; this should be the dorsal aspect of the ventral plate of the sacrum. The needle is then withdrawn slightly and redirected so that the angle of insertion relative to the skin surface is decreased. In male patients, this angle will be almost parallel with the tabletop, whereas in female patients a slightly steeper angle will be necessary (needle position 2).

Potential Problems

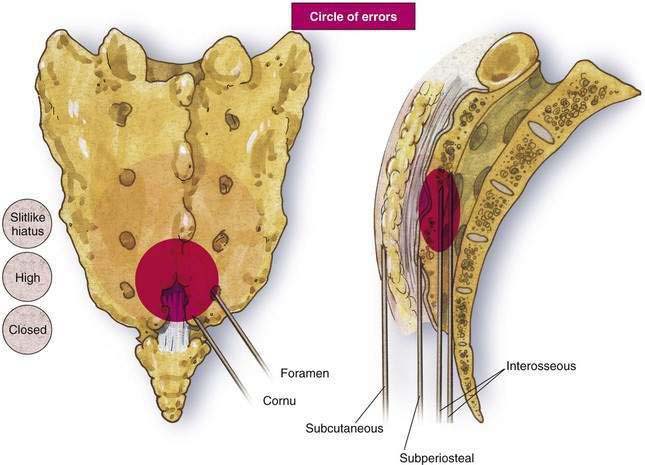

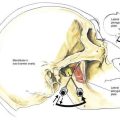

Perhaps the most frequent problem with caudal anesthesia is ineffective blockade, which results from the considerable variation in the anatomy of the sacral hiatus. If anesthesiologists are unfamiliar with caudal technique and the needle passes anterior to the ventral plate of the sacrum, puncture of the rectum or, in obstetric anesthesia, of fetal parts is possible. As illustrated in Figure 42-7, the area surrounding the sacral hiatus can be imagined as a potential “circle of errors.” The practitioner may be faced with a slitlike hiatus that does not allow easy needle insertion; the hiatus may be located more cephalad than anticipated or in fact may be closed. Likewise, loss of resistance may be encountered as the needle is inserted into one of the sacral foramina rather than the hiatus. In the lateral view, it is obvious that needles may be misdirected into subcutaneous or periosteal locations as well as into the marrow of sacral bones.

Pearls

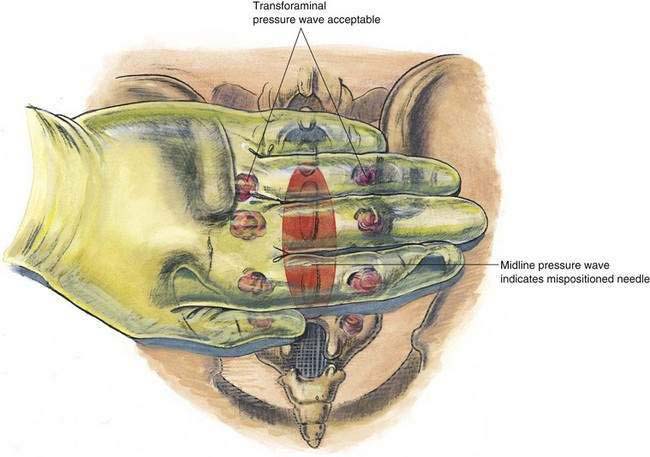

One helpful hint that will confirm needle location when carrying out caudal anesthesia is illustrated in Figure 42-8. Once the needle has entered what is thought to be the caudal canal, the anesthesiologist should place a palpating hand across the sacral region dorsally. Then, 5 mL of saline solution should be rapidly injected through the caudal needle. By placing the hand as shown, the anesthesiologist should be immediately aware of the subcutaneous needle position overlying the sacrum. If the needle is mispositioned subcutaneously, a bulge during injection will develop in the midline. If the needle is correctly positioned in the caudal canal, no midline bulge should be palpable. In thin individuals, accurate needle placement in the caudal canal and rapid injection of solution may allow the anesthesiologist to feel small pressure waves more laterally overlying the sacral foramina. These smaller pressure waves should not be confused with those associated with a misplaced subcutaneous needle.