INTRODUCTION

CASE IN DETAIL

KG presented to a rural base hospital 2 months ago with severe recurrent epistaxis associated with easy bruising of 3 weeks’ duration. He denied any other mucosal bleeding or symptoms of anaemia. On investigation, he was diagnosed with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and initially treated with high-dose oral corticosteroids for 2 weeks. Despite treatment, his platelet count failed to recover and his symptoms persisted. He denied any steroid-associated side effects such as weight gain, insomnia, mood swings or oral candidiasis during this period. He had further investigations, including a bone marrow biopsy, and the diagnosis was not altered. He was then transferred to a hospital in the city for further treatment with intravenous normal immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis. The response to this treatment was suboptimal. At this point it was decided to carry out therapeutic splenectomy, which he is currently awaiting. Meanwhile he is managed on prednisolone 35 mg daily. He still experiences occasional epistaxis and skin bruising, but it is less severe than at presentation.

He had an acute myocardial infarction 3 months ago, from which he has made an uneventful recovery. Follow-up coronary angiography revealed the existence of double-vessel coronary disease and he is managed on medical anti-ischaemia therapy. He denies any ongoing angina or dyspnoea. He is currently on atenolol 50 mg daily, enalapril 10 mg mane and topical nitrate 25 mg 8 am to 8 pm daily. He denies any side effects associated with this therapy. He has the following risk factors for ischaemic heart disease: male sex, a past smoking history of 40 pack-years (he gave up smoking 4 weeks ago) and hypertension.

He was diagnosed with hypertension 9 years ago and has been managed on different medications. He is currently on amlodipine 5 mg twice daily and denies having any side effects associated with this medication. His general practitioner monitors his blood pressure, but not regularly. He has been told that his blood pressure is well controlled.

He denies any risk-prone behaviour for HIV infection.

His current medications in summary are atenolol, enalapril, nitrate patch, amlodipine and prednisolone. He is not on any therapeutic agent that is known to cause thrombocytopenia. He has no known allergies.

KG’s family history is unremarkable for any significant medical condition. His father died at the age of 87 and mother at the age of 84, and he is not aware of the causes of their deaths. His brother, aged 57, is well.

He worked as a clerk and is currently retired on an age pension, which is barely adequate to meet his and his wife’s needs.

KG is from a rural town more than 1000 km from the city, where he lives with his wife, aged 60. His wife is well. They have been married for 40 years and have two daughters, aged 37 and 40, both well, married, and living separately but still in the same town.

He is independent with his activities of daily living. He sees his GP only rarely. He lives in a house with two steps at the entrance and has no difficulty negotiating these.

The dietary history reveals satisfactory nutrition and he denies any problems with sleep. He consumes alcohol only on social occasions (less than 40 g per week).

While in hospital in the city for the past 2 weeks, only his wife has been visiting him. His wife stays at the accommodation facility provided by the hospital.

He has satisfactory insight into his condition.

ON EXAMINATION

KG is a moderately obese man. He was alert and cooperative. He was receiving normal saline through an intravenous cannula in his right forearm, the entry site of which appeared inflamed with surrounding erythema, warmth and tenderness.

His respiratory rate was 12 at rest, pulse rate 90 per minute. His blood pressure was 130/85 mmHg and he was afebrile. His estimated body mass index was 30 kg/m3.

He had diffuse non-palpable purpura over the dorsal and ventral aspects of his lower limbs distally and proximally, bilaterally. There were several ecchymoses in the dorsal aspect of his thorax. There was no evidence of mucosal bleeding or conjunctival pallor. His per rectum examination showed no evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding. There was no lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly.

In the cardiovascular examination, the jugular venous pressure was not elevated. His apex beat was palpable in the fifth intercostal space in the mid-clavicular line. The heart sounds were dual and normal. All his peripheral pulses were clearly palpable.

The examination of the respiratory and neurological systems were unremarkable. Surprisingly, there was no proximal muscle weakness.

His abdomen was soft and non-tender and there were no organomegaly or masses. There was moderate abdominal obesity but no purple striae.

Musculoskeletal examination was unremarkable and there was no bony tenderness, including in the vertebral column.

In summary, my impression is of a 64-year-old man presenting with symptomatic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura resistant to steroid therapy and necessitating splenectomy. He also has a history of hypertension and his situation is complicated by a recent myocardial infarction.

The two main issues with this man are the risk of haemorrhage and the risk of sustaining a myocardial insult perioperatively during splenectomy.

In approaching the management of this man, I have identified an incidental urgent medical problem, two semi-urgent medical problems and one social problem.

In approaching the management of these problems, first I would like to see his full blood count, to estimate the severity of the thrombocytopenia and to exclude any haematological malignancy. I would also like to see the results of the serology test for antiplatelet antibodies, and the recent bone marrow biopsy.

In addition, I would like to see the results of an autoimmune screen (antinuclear antibody and antibody to extractable nuclear antigen), rheumatoid factor level, thyroid function tests and antibody titres to common viral antigens.

Although he denies any risk-prone behaviour, given the resistant nature of his thrombocytopenia I would also consider testing him for HIV infection.

Questions and answers

Q: His platelet count is 20 × 109/L. Do you agree with the proposed therapeutic plan?

A: Despite treatment with high-dose systemic steroids, intravenous normal immunoglobulin and plasmaphaeresis, his platelet count still stands at 20. He also suffers from spontaneous bleeding. To prevent significant haemorrhage and spare him the adverse effects of steroid therapy, I believe that, although risky, splenectomy is highly indicated.

Q: Why do you ask for the antiplatelet antibody test, the autoimmune screen and the thyroid function test results?

A: The antiplatelet antibody test is not essential for the diagnosis of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and only 60–70% of patients with the disease would actually test positive. But the presence of a positive result would help confirm the diagnosis, particularly in the setting of poor primary response to corticosteroids. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion.

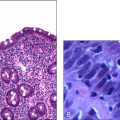

Q: Please interpret this bone marrow biopsy result.

A: There is megakaryocytosis, which is consistent with the current diagnosis of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. The rest of the picture is normal and therefore the possibilities of bone marrow infiltration by a malignant process as well as marrow aplasia are excluded. This bone marrow picture can also suggest hypersplenism, but I did not find clinical splenomegaly and this man has no known history of chronic liver disease as a cause of splenomegaly.

Q: How would you manage this patient?

A: The initial management issue involves the diagnosis and, if possible, the control of the thrombocytopenia. Given the diagnosis of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, I would initially try high-dose oral corticosteroids in the form of prednisolone 60 mg daily with daily platelet counts. The majority will respond initially, but only 20% of patients have a sustained response. If the response was poor with steroid treatment alone, as is the case with KG, I would arrange for splenectomy. Splenectomy will improve the chances of sustained remission to 60%. If the thrombocytopenia persists in spite of splenectomy, I would consider treatment with danazol or immunosuppression with azathioprine.

Q: How would you prepare this patient for splenectomy?

A: There are three main issues that concern me regarding this man undergoing splenectomy. First, his cardiovascular fitness to undergo general anaesthesia and a major surgical procedure, given his history of a recent myocardial infarction. He runs a significant risk of reinfarction and possible death, so I would further evaluate his risks in that regard and weigh them against the expected benefits. Second, his current platelet count, as he is significantly thrombocytopenic (20 × 109/L). I would consider intravenous normal immunoglobulin infusion with or without platelet transfusion immediately before surgery, for a rapid elevation of the platelet count. The third issue of concern is the infection risk associated with splenectomy.

Q: How would you address the septic risks associated with splenectomy?

A: Post splenectomy, this man is at risk of suffering from fulminant sepsis due to encapsulated organisms such as Meningococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, so he needs to be vaccinated against these organisms. He should be administered pneumococcal vaccine 3 weeks prior to the operation and the vaccine should be repeated at 5-yearly intervals. He should also receive H. influenzae type B vaccine if he has not been immunised before. Meningococcal vaccination would be necessary only if he was travelling to an area where Meningococcus type A was endemic. Unfortunately, there is no vaccination available against type B, which is the prevalent form in the Western world.

Q: Would you advise the surgeons to operate on this man, and if so, when?

A: This man has an angiographic diagnosis of double-vessel disease and has been recommended medical therapy. But the more important risk is his recent acute myocardial infarction, which predisposes him to perioperative myocardial insult. During the first 3 months after an acute myocardial infarction, the risk of perioperative infarction is at its highest, at about 6%. This risk dwindles to 2.5% after 4 months. So before deciding on surgery for splenectomy it is important to weigh the benefits against the risks.

With the current level of thrombocytopenia he runs the significant risk of a major spontaneous bleed, with significant morbidity and possibly mortality. So it is important to attempt disease control with splenectomy.

As he had his infarction only 3 months ago, I would endeavour to postpone the operation by at least another month while closely monitoring his platelet count with maximum medical therapy. If the platelet count did not improve, I would go ahead with the splenectomy.

Q: How would you manage the cardiac risk that this man has in association with an operation?

A: This man’s perioperative risk of a myocardial insult can be regarded as substantial but not extremely high, due to his stable functional capacity and the good symptom control afforded by his anti-ischaemia therapy.

I would formally evaluate his functional capacity by performing an exercise stress test, and if his functional capacity was more than 5 METs I would recommend surgery with less reservation. Perioperatively I would closely supervise his cardiac and haemodynamic function with systemic and pulmonary arterial monitoring. I would monitor his cardiac function intraoperatively and postoperatively with continuous electrocardiography. I would perform 6-hourly troponin I levels intraoperatively and postoperatively during the first 24 hours. It has been observed that most perioperative acute myocardial infarctions occur during the first few days postoperatively.

The fact that he is on a beta-blocker may offer further protection against a perioperative cardiac insult. I would ensure strict control of his blood pressure and heart rate during this period.

Q: How would you plan to manage his social problems?

A: He and his wife need better social support while in the city. I would get together with the social worker to formulate a plan to provide the necessary support. First I would look into the possibility of organising for the rest of his family from home to visit him. I would then see whether they had any relatives or friends in the city who might provide help and support. In addition, I would look into the services run by government and voluntary organisations (e.g. church groups, social service organisations) that might be of some help.

Q: KG has a blood sugar level (BSL) of 11.1 mmol/L. What do you think of this blood test report?

A: This result suggests hyperglycaemia consistent with a diagnosis of diabetes. I would repeat the test for confirmation and also check his glycosylated haemoglobin level, looking for an elevation. The most likely cause for this picture is his prednisolone therapy. But incidental diagnosis of latent chronic diabetes mellitus cannot be excluded.

It is important to control his blood sugar level well, given his existing coronary artery disease. First I would put him on a strict diabetic diet and monitor his blood sugar level. If the level remained significantly high, I would treat him with insulin until he had his splenectomy and the prednisolone was stopped. I would also check his fasting lipid profile, looking for hypercholesterolaemia, and perform a urinalysis, looking for proteinuria or microalbuminuria. I would commence him on a statin agent regardless of his cholesterol level, given that he has established coronary artery disease.