CHAPTER 38 Carpal Anatomy

Historical Background

The bones that make up the carpal wrist have names with ancient origins. The name of the scaphoid is derived from the Greek word scaphe, which means “boat” or “trough.”1 The lunate was previously named the semilunar due to its resemblance to the moon, and the translation of lunate is “crescent shaped.” The capitate is also known as the os magnum because it is the largest bone in the carpus. Finally, the pisiform translates to “pea,” which matches the size and shape of this bone.

Much of the modern original work in the anatomy of the wrist was performed by Landsmeer, whose painstaking dissection was the basis for the names of many wrist ligaments. Landsmeer published his atlas of hand anatomy2 and coauthored a landmark paper with Berger describing the extrinsic ligament anatomy of the carpus.3

Osseous Anatomy

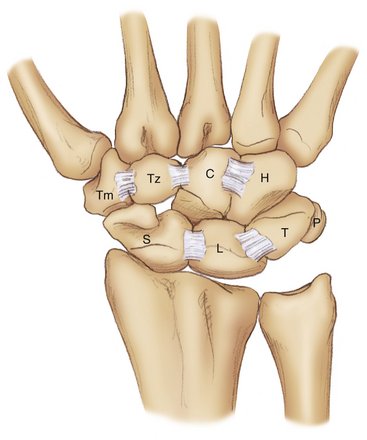

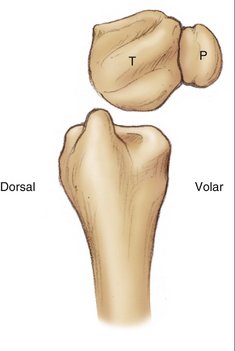

The wrist is the link between the forearm and the hand. The carpus is made up of 15 bones excluding the sesamoids and supernumerary bones (Fig. 38-1). These include the distal radius and ulna, the two rows of the carpus, and the bases of the five metacarpals. The carpal rows are divided into the proximal and distal carpal rows. In the proximal carpal row are found the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform. The pisiform articulates only with the triquetrum, because it lies volar to it and is enveloped by the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon except on its deep surface (Fig. 38-2). The pisiform is considered by many to be a sesamoid bone but provides an important lever arm for the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon. The trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate make up the distal carpal row from radial to ulnar in the wrist. The hook of the hamate extends volarly 1 to 2 cm radial and distal to the pisiform and serves as the attachment site for several ligaments.1 The five metacarpal bases articulate with this row of carpal bones.

The carpus includes three specific joint types: the radiocarpal joint, the midcarpal joint, and the carpometacarpal joints. The radiocarpal joint is composed of the distal articular surface of the radius in addition to the triangular fibrocartilage complex. The distal radius has two articular facets, named after the carpal bone they contact—the scaphoid and lunate facets, respectively.4 The facets on the radius are divided by the interfossal ridge, which is often a raised portion of the radius but can also have a fibrous ridge to it. The distal radius and triangular fibrocartilage complex articulate as a whole with the proximal carpal row, which forms a convex articular facet.

Ligamentous Anatomy

All of the ligaments of the wrist are intracapsular with the exception of three ligaments: the transverse carpal ligament, or flexor retinaculum, the pisohamate ligament, and the pisometacarpal ligament. Nearly all the wrist ligaments are contained within capsular sheaths of loose connective tissue and fat. This often makes it difficult to visualize individual ligaments when approaching the carpal joints surgically. From within the joints, the ligaments can be viewed as distinct structures, best seen during wrist arthroscopy or visualizing the volar ligaments via a dorsal approach between the carpal bones.5,6

Extrinsic Carpal Ligaments

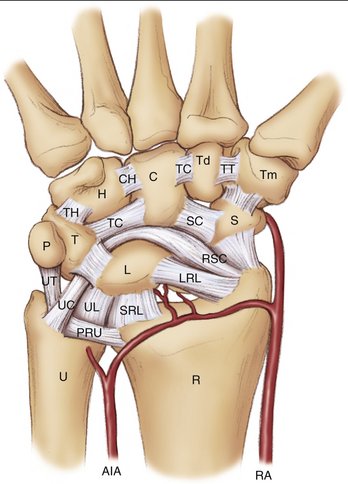

The extrinsic ligaments of the carpus provide support and form the linkage between the long bones of the forearm and the eight carpal bones. The volar extrinsic ligaments form an inverted “V”-shaped configuration and are best visualized during wrist arthroscopy. In fact, visualization of the ligaments from outside the wrist joint is nearly impossible as the capsule of the wrist blends the extrinsic ligaments together. These ligaments include the radioscaphocapitate, long radiolunate, radioscapholunate, and short radiolunate ligaments on the radial carpus. The ulnolunate, ulnolunocapitate, and ulnotriquetrocapitate ligaments form the volar ulnar ligamentous complex (Fig. 38-3).

On the radial side of the wrist, the radioscaphocapitate ligament originates in a broad sheet from the tip of the radial styloid to the midscaphoid fossa and inserts on the distal scaphoid pole, acting as a support to the waist of the scaphoid. The next ulnar ligament is the long radiolunate ligament, which originates from the remaining portion of the scaphoid fossa of the radius and attaches to the radial volar aspect of the lunate.3 Abutting the long radiolunate ligament is the radioscapholunate ligament (or ligament of Testut), which is not actually a true ligament but is rather a capsular tissue through which course blood vessels, including terminal branches of the anterior interosseous artery.7 This structure goes through the volar capsule and attaches dorsally into the scapholunate interosseous ligament. Finally, the short radiolunate ligament has its origin from the lunate fossa and inserts onto the radial side of the lunate (Fig. 38-4).8

The ulnocarpal complex includes the most superficially located ulnocapitate ligament, which originates from the ulnar fovea, passing volarly to support the lunotriqetral interosseous ligament, and inserts partially onto the capitate and mostly blends into the radioscaphocapitate ligament. The ulnolunate and ulnotriquetral ligaments are interdigitated proximally as they originate from the palmar radioulnar ligament and then split to attach distally to the lunate and triquetrum, respectively.8

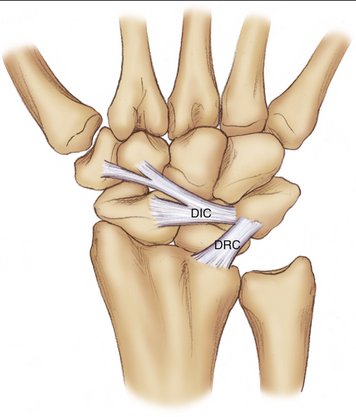

Based on the definition of extrinsic ligaments connecting to bones outside the carpus, there is a single dorsal extrinsic ligament, the dorsal radiocarpal or radiotriquetral ligament. The dorsal intercarpal ligament, which lies at the same level but connects the scaphoid, trapezium, and trapezoid to the triquetrum, is often classified as an extrinsic ligament. This ligament complex, which forms a lateral “V” shape, has been shown to indirectly stabilize the scaphoid dorsally during wrist range of motion (Fig. 38-5).9

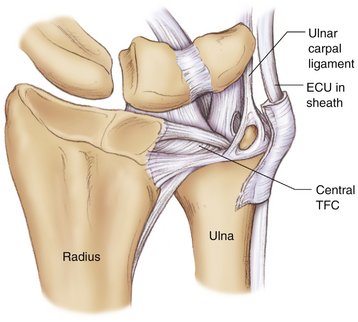

The distal radioulnar joint ligaments provide important stability to this construct. The triangular fibrocartilage complex includes the dorsal and palmar radioulnar ligaments (Fig. 38-6). The dorsal radioulnar ligament originates at the dorsal rim of the radius at the sigmoid notch and inserts into the ulnar fovea and ulnar styloid. This ligament also contributes fibers to the subsheath of the extensor carpi ulnaris through a separate extension of its most superficial portion. The palmar radioulnar ligament has a volar origin, also at the level of the sigmoid notch of the radius. This ligament also inserts onto the ulnar styloid and fovea, and its fibers blend with those of the dorsal radioulnar ligament at that level. The superficial portion of the palmar radioulnar ligament then forms the ulnolunate and ulnotriquetral ligaments, with the fibers angulating distally. At the level of the ulnar styloid is found the ligamentum subcruentum, defined by Henle as the loose vascular tissue surrounding the volar prestyloid recess.10 On the dorsal side of the wrist, proximal to the dorsal radioulnar ligament, is found a metaphyseally based ligament that courses distally to interdigitate with the dorsal radioulnar ligament. This is the dorsal radial metaphyseal arcuate ligament,11 which also contributes to the extensor carpi ulnaris subsheath (see Fig. 38-6).

Intrinsic Carpal Ligaments

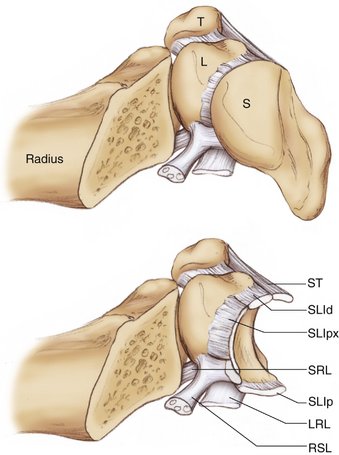

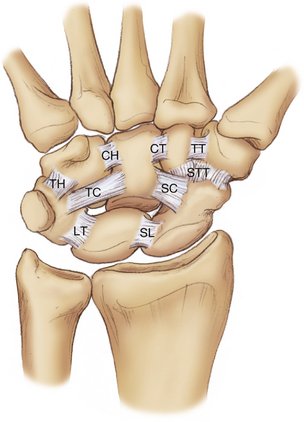

In the proximal carpal row, the intrinsic ligaments include the scapholunate interosseous ligament (SLIL) and lunotriquetral interosseous ligament (LTIL) (Fig. 38-7). Each of these ligaments is divided histologically into different segments: the dorsal, volar, and proximal portions. In the SLIL, studies have shown that the dorsal region is the thickest and strongest, with the palmar segment being thin and obliquely oriented. The proximal segment is made up of fibrocartilage, with no collagen fibers. The LTIL, in contrast, is thickest volarly and interdigitates with fibers of the ulnocapitate ligament as it passes volarly over the LTIL. The dorsal region is thin and the proximal portion is, like the SLIL, made up of fibrocartilage.11

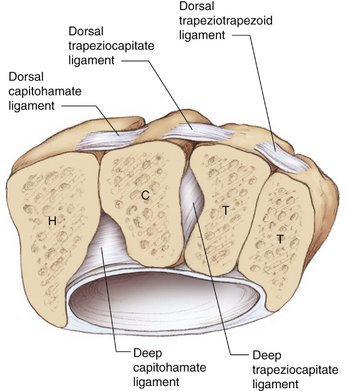

In the distal carpal row, the trapeziotrapezoid, trapeziocapitate, and capitohamate ligaments comprise the intrinsic ligaments. Again, each ligament is made up of a dorsal and volar region. The trapeziotrapezoid ligament covers the entire length of the respective carpal bones. In contrast, the trapeziocapitate and capitohamate ligaments insert on the body of the capitate because of the need for proximal extension of the capitate head and neck. A thick deep trapeziocapitate ligament courses at an angle through a notch between the trapezoid and capitate. Similarly, the capitohamate ligament has a deep component that is quite thick and strong, lying within a depression at the volar distal edge of the capitate and hamate articulation. It also extends to the third and fourth metacarpal bases (Fig. 38-8).8

Between the two rows course the palmar midcarpal ligaments, running from the scaphoid and triquetrum to the bones of the distal carpal row (see Fig. 38-7). The arcuate ligament forms the central third of the palmar midcarpal capsule and is composed of the blended fibers of the radioscaphocapitate and ulnocapitate ligaments. These form an important support to the head of the capitate. On the radial side of the midcarpal joint, the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid ligament attaches to the radial and ulnar sides of the scaphoid and then divides into two bands. The scaphotrapezial band connects the scaphoid and trapezium, with fibers forming a “V” shape. The scaphotrapezoid band connects the ulnar aspect of the scaphoid to the volar trapezoid. The scaphocapitate ligament spans the distal scaphoid pole to the palmar aspect of the capitate body. On the ulnar midcarpal side, the triquetrocapitate ligament connects the distal radial portion of the triquetrum to the ulnar side of the capitate body. Finally, the triquetrohamate ligament originates just ulnar to the triquetrocapitate ligament on the triquetrum and attaches to the volar hamate body.8 Additionally, the dorsal intercarpal ligament, or scaphotriquetral ligament, is classified as an intercarpal ligament because of its broad connection between carpal bones.

Vascular Anatomy

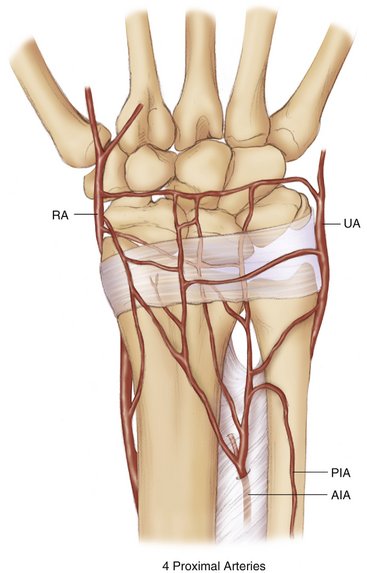

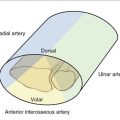

There are four orthograde sources of blood flow to the wrist. These four extraosseous vessels contribute nutrient vessels to the distal radius and ulna and include the radial, ulnar, anterior and posterior interosseous arteries. The anterior interosseous artery divides into anterior and posterior divisions proximal to the distal radioulnar joint. The posterior division and the radial artery form the primary sources of orthograde blood flow to the distal radius (Fig. 38-9).12

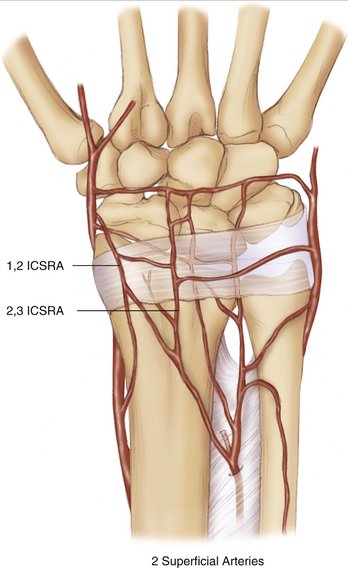

The vessels supplying the dorsal radius and ulna are best described by their relationship to the extensor compartments of the wrist and extensor retinaculum. They are considered intercompartmental when located between compartments and compartmental when lying within an extensor compartment. There are two consistent intercompartmental vessels that lie superficial to the retinaculum and are described as supraretinacular. These two vessels, the 1,2 and 2,3 intercompartmental supraretinacular arteries, are located on the retinaculum between their named compartments (Fig. 38-10).12,13

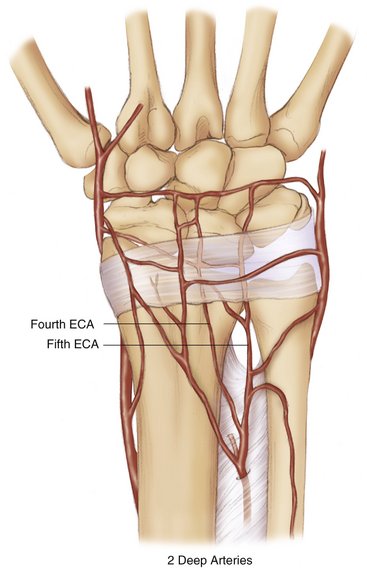

Two consistent vessels are found in the fourth and fifth compartments. They lie on the surface of the radius in the floor of the fourth and fifth extensor compartments and are named the fourth and fifth extensor compartment arteries (Fig. 38-11).12,13

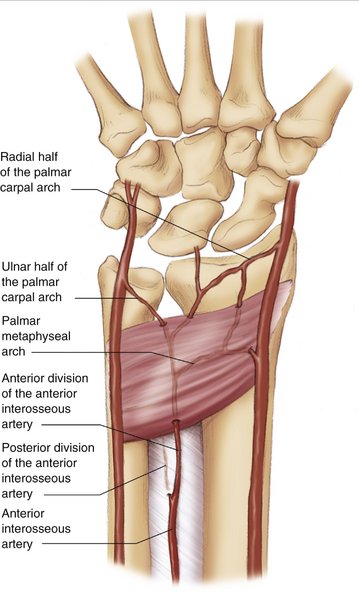

On the volar aspect of the arm, the palmar carpal arch arises approximately 1.5 cm proximal to the radial styloid and courses volar to the pronator quadratus. It anastomoses with the anterior interosseous artery and continues as the ulnar carpal artery to then anastomose with the ulnar artery. In its path it gives off many cortical perforating branches and supplies the proximal radiocarpal joint at that level (Fig. 38-12).14

Nerve Anatomy

The carpus is innervated by articular branches of the anterior and posterior interosseous nerves, the superficial radial nerve, the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve, and the dorsal and motor branches of the ulnar nerve. In addition, the dorsal, lateral, and medial cutaneous nerves of the forearm have been variably shown to contribute articular twigs to the wrist.15

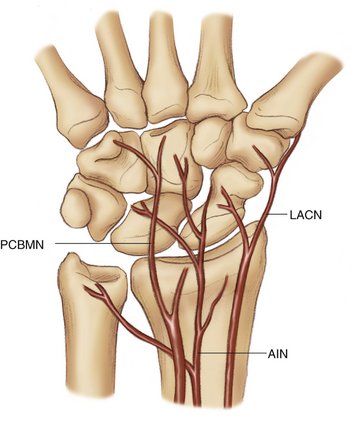

On the volar side of the wrist, the anterior interosseous nerve has several small branches that travel deep to the pronator quadratus muscle and enter the volar wrist capsule but do not penetrate to the periosteum.16,17 On the radial volar wrist, the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve gives off branches to the wrist capsule and periosteum. The palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve has an articular branch that terminates in the intercarpal ligaments. Finally, the ulnar nerve has been described as having one or two articular branches on the volar ulnar side of the carpus (Fig. 38-13).17

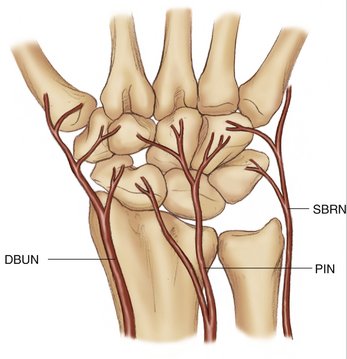

At the dorsal carpus, the posterior interosseous nerve is the dominant source of wrist innervation. This terminal branch of the radial nerve supplies articular branches to the periosteum and capsule. The superficial radial nerve also contributes articular branches to the dorsal capsule and to the periosteum, as does the dorsal sensory branch of the ulnar nerve (Fig. 38-14).17

1. Eathorne SW. The wrist: clinical anatomy and physical examination—an update. Prim Care.. 2005;32:17-33.

2. Landsmeer JMF. Atlas of Anatomy of the Hand. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1976.

3. Berger RA, Landsmeer JM. The palmar radiocarpal ligaments: a study of adult and fetal human wrist joints. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1990;15:847-854.

4. Stuchin SA. Wrist anatomy. Hand Clin.. 1992;8:603-609.

5. Bettinger PC, Cooney WP3rd, Berger RA. Arthroscopic anatomy of the wrist. Orthop Clin North Am.. 1995;26:707-719.

6. Berger RA. Arthroscopic anatomy of the wrist and distal radioulnar joint. Hand Clin.. 1999;15:393-413.

7. Berger RA, Blair WF. The radioscapholunate ligament: a gross and histologic description. Anat Rec.. 1984;210:393-405.

8. Berger RA. The anatomy of the ligaments of the wrist and distal radioulnar joints. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 2001:32-40.

9. Viegas SF, Yamaguchi S, Boyd NL, Patterson RM. The dorsal ligaments of the wrist: anatomy, mechanical properties, and function. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1999;24:456-468.

10. Kauer JM. The articular disc of the hand. Acta Anat (Basel).. 1975;93:590-605.

11. Berger RA. The ligaments of the wrist: a current overview of anatomy with considerations of their potential functions. Hand Clin.. 1997;13:63-82.

12. Sheetz KK, Bishop AT, Berger RA. The arterial blood supply of the distal radius and ulna and its potential use in vascularized pedicled bone grafts. J Hand Surg.. 1995;20:902-914.

13. Shin AY, Bishop AT. Vascular anatomy of the distal radius: implications for vascularized bone grafts. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 2001;383:60-73.

14. Haerle M, Schaller HE, Mathoulin C. Vascular anatomy of the palmar surfaces of the distal radius and ulna: its relevance to pedicled bone grafts at the distal palmar forearm. J Hand Surg [Br].. 2003;28:131-136.

15. Buck-Gramcko D. Denervation of the wrist joint. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1977;2:54-61.

16. Svizenska I, Cizmar I, Visna P. An anatomical study of the anterior interosseous nerve and its innervation of the pronator quadratus muscle. J Hand Surg [Br].. 2005;30:635-637.

17. Van de Pol GJ, Koudstaal MJ, Schuurman AH, Bleys RL. Innervation of the wrist joint and surgical perspectives of denervation. J Hand Surg [Am].. 2006;31:28-34.