Objectives

• Describe critical care nursing roles.

• Discuss the importance of holistic care for the critically ill patient and family.

• Compare and contrast interdisciplinary critical care management models and tools.

![]()

Be sure to check out the bonus material, including free self-assessment exercises, on the Evolve web site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Urden/priorities/.

Critical Care Nursing Roles

Nurses provide and contribute to the care of critically ill patients in a variety of roles. The most prominent role for the professional registered nurse (RN) is that of direct care provider. Other nurse clinicians also contribute to patient care, including patient educators, cardiac rehabilitation specialists, physician’s office nurses, and infection control specialists. The specific types of expanded-role nursing positions are determined by individual organizational resources and needs.

Advanced-practice nurses (APNs) have met educational and clinical requirements beyond the basic nursing educational requirements for all nurses. The APNs in critical care areas are predominantly the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) and the acute care nurse practitioner (ACNP). APNs have a broad depth of knowledge and expertise in their specialty area and manage complex clinical and systems issues. The organizational system and existing resources of an institution determine what roles may be needed and how these roles function.

CNSs serve in specialty roles that require their clinical, teaching, research, leadership, and consultative abilities. In addition to providing education and mentoring to staff nurses, they work in direct clinical roles, systems or administrative roles, and in various other settings in the health care system. They may be organized by specialty, such as cardiovascular, or function, such as cardiac rehabilitation. CNSs also may be designated as case managers for specific patient populations.

Nurse Practitioners (NPs) and ACNPs manage clinical care of a group of patients and have various levels of prescriptive authority, depending on the state and practice area in which they work. They also provide care consistency, interact with families, plan for patient discharge, and provide teaching to patients, families, and other members of the heath care team.1

Critical Care Nursing Standards

The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) has established nursing standards to provide a framework for critical care nurses. The standards are authoritative statements that describe the level of care and performance by which the quality of nursing care can be judged. Standards serve as descriptions of expected nursing roles and responsibilities.2 The six AACN Standards of Care for Acute and Critical Care Nursing Practice are prescriptive of a competent level of nursing practice: assessment, diagnosis, outcomes identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Evidence-Based Nursing Practice

Much of early medical and nursing practice was based on nonscientific traditions that resulted in variable and haphazard patient outcomes.3 These traditions and rituals, which were based on folklore, gut instinct, trial and error, and personal preference, were often passed down from one generation of practitioners to another.3–5 Examples of nonscientific-based critical care nursing practice include suctioning artificial airways every two hours, using iced saline injectable when measuring cardiac output, always using lead II for cardiac monitoring, stripping chest tubes every two hours, and limiting visiting hours for all patients.4

The dramatic and multiple changes in health care and the ever-increasing presence of managed care in all geographic regions have placed greater emphasis on demonstrating the effectiveness of treatments and practices on outcomes.6,7 In addition, emphasis is greater on efficiency, cost-effectiveness, quality of life, and patient satisfaction ratings.8 It has become essential for nurses to use the best data available to make patient care decisions and carry out the appropriate nursing interventions.8 By means of a scientific basis, with its ability to explain and predict, nurses are able to provide research-based interventions with consistent, positive outcomes. The content of this book is evidence based, with the most current, cutting-edge research abstracted and placed throughout the chapters as appropriate to topical discussions.

The increasingly complex and changing health care system presents multiple challenges for creating an evidence-based practice. Not only must appropriate research studies be designed to answer clinical questions, but also research findings must be used to make necessary changes for implementation in practice.9 Multiple evidence-based practice and research utilization models exist to guide practitioners in the use of existing research findings. One such model is the Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care, which incorporates both evidence and research as the basis for practice.10 Inquisitive practitioners who strive for best practices using valid and reliable data will demonstrate quality outcomes-driven care and practices.11

Evidence-based nursing practice considers the best research evidence on the care topic, along with clinical expertise of the nurse, and patient preferences.12 For instance, when determining the frequency of vital sign measurement, the nurse would use available research, nursing judgment (stability, complexity, predictability, vulnerability, and resilience of the patient),13 along with the patient’s preference for decreased interruptions and the ability to sleep for longer periods of time. At other times the nurse will implement an evidence-based protocol or procedure that is based on evidence, including research. An example of an evidence-based protocol is one in which the prevalence of indwelling catheterization and incidence of hospital-acquired catheter-associated urinary tract infections in the critical care unit can be decreased.14

The AACN has promulgated several practice summaries in the form of a “Practice Alert.” These alerts are short directives that can be used as a quick reference for practice areas (e.g., oral care, noninvasive blood pressure monitoring, ST segment monitoring). They are succinct, supported by evidence, and address both nursing and multidisciplinary activities. Each alert includes the clinical information, followed by references that support the practice.15

Holistic Care

The high-technology–driven critical care environment is fast paced and directed toward monitoring and treating life-threatening changes in patient conditions. For this reason, attention is often focused on the technology and treatments necessary for maintaining stability in the physiological functioning of the patient. Great emphasis is placed on technical skills, professional competence, and responsiveness to critical emergencies. Concern has been voiced about the lesser emphasis on the caring component of nursing in this fast-paced, highly technological health care environment.16,17 Nowhere is this more evident than in areas where critical care nursing is practiced. Keeping the care in nursing care is one of the greatest challenges.17 The critical care nurse must be able to deliver high-quality care skillfully, using all applicable technologies, while incorporating psychosocial and other holistic approaches as appropriate to the time and the patient’s condition.

The caring aspect is fundamental to the nurse-patient relationship and to the health care experience. Holistic care focuses on human integrity and stresses that the body, mind, and spirit are interdependent and inseparable. Thus all aspects need to be considered in planning and delivering care.18,19

Health care providers clearly understand that a patient’s physical condition progresses in fairly predictable stages, depending on the presence or absence of comorbid conditions. Less clearly understood is the effect of psychosocial issues on the healing process. For this reason, special consideration must be given to determining the unique interventions that will positively impact each individual patient and help the patient progress toward desired outcomes.

An important aspect in the care delivery to—and recovery of—critically ill patients is the personal support of family members and significant others. The value of both patient-centered and family-centered care should not be underestimated.20 It is important for families to be included in care decisions and to be encouraged to participate in the care of the patient as appropriate for the patient’s level of needs and the family’s level of ability.

Cultural diversity in health care is not a new topic but is gaining emphasis and importance as the world becomes more accessible to all as the result of increasing technologies and interfaces with places and peoples. Diversity includes not only ethnicity but also differences in lifestyles, opinions, values, and beliefs.

Unless cultural differences are taken into account, optimal health care cannot be provided. More attention has been directed recently at determining the physiological and disease development and progression differences among various ethnic groups. Mortality rates from cardiovascular disease are significantly higher for both black men and black women than for white men and white women. The prevalence of coronary heart disease is highest in black women, followed by Mexican American men.21 Care providers must develop an increased sensitivity to the health care needs and vulnerabilities of all groups.

Cultural competence is one way to ensure that individual differences related to culture are incorporated into the plan of care.22,23 Nurses must possess knowledge about biocultural, psychosocial, and linguistic differences in diverse populations to make accurate assessments.

Interventions must then be tailored to address the uniqueness of each patient and family.

Spirituality can become more important as people search for meaning and guidance in critical, emergent, and unexpected tragic circumstances.24 Likewise, many health care practitioners turn to their own spirituality to manage stress and find answers to the health care issues that they face on a daily basis. Spiritual practices consist of meditation, prayer, and spiritual materials and are based on personal values and beliefs. Holt-Ashley24 describes how to incorporate prayer into the critical care unit, concentrating on patients and families and the nurse. The author also offers strategies for creating an environment that is conducive to spiritual well-being for both patients and staff.

Nursing’s Unique Role in Critical Care

Researchers have studied critical care nurses to better understand their clinical judgment and interventions and the link between the two. They identified two major categories of thought and action and nine categories of practice that illustrate clinical judgment and the clinical knowledge development of critical care nurses. These major categories25 are delineated in Box 1-1.

Critical care nurses are essential in facilitating communication among all health care providers, patients, and their families. They must be confident and assertive when talking with care providers, communicating essential information and advocating for patients. Communication skills are as important as clinical skills to ensure that the appropriate actions and interventions are done. Nurses also must be knowledgeable about the latest evidence to support their practice and share this and mentor others on the team. The critical care nurse plays a crucial team role in formulating patient care goals.26

Interdisciplinary Critical Care Management

The managed care environment has placed emphasis on examining methods of care delivery and processes of care by all health care professionals. Partnerships have been formed or strengthened, with a focus on increasing quality of care and services while containing or decreasing costs. Coordination of care in critical care units has been demonstrated to influence patient outcomes significantly.27

Thornby28 discussed the importance of skilled communication as essential to excellent patient care and a climate of safety. Ineffective nurse-physician communication has been related to adverse patient events, and nurse burnout and turnover.29 Gerardi and Fontaine30 described a model of true collaboration that could be used to improve interdisciplinary communications and ultimately to have a positive impact on patient outcomes. In this model, there is a continuum of collaboration that has seven components: self-awareness, information sharing, negotiation, feedback, conflict engagement, conflict resolution, and forgiveness and reconciliation. Successfully working through these stages will result in a collaborative environment.

Case Management

Case management is the process of overseeing the care of patients and organizing services in collaboration with the patient’s physician or primary health care provider. The case manager may be a nurse, allied health care provider, or the patient’s primary care provider. Case managers are usually assigned to a specific population group, and they facilitate effective coordination of care services as patients move in and out of different settings. Ideally, the case manager oversees the care of the patient across the continuum of care.

Outcomes Management

Outcomes management refers to a model aimed at managing the outcomes of care by the use of various tools, quality improvement processes, and interdisciplinary team involvement and action. Specifically, emphasis is placed on consistent standards of care, measurement of disease-specific clinical outcomes, patient functioning and well-being, and assessment of clinical and outcome data for the specific conditions.31 Outcomes management also takes place in multiple settings across the continuum of care. Professional nurse outcomes managers ensure that variances from the plan of care are addressed in a timely manner. They also examine aggregate information with the team for quality improvement in the interdisciplinary plan of care.

Care Management Tools

Many quality improvement tools are available to providers for care management.

Algorithm

An algorithm is a stepwise decision-making flowchart for a specific care process or processes. Algorithms are more focused than clinical pathways and guide the clinician through the “if, then” decision-making process, addressing patient responses to particular treatments. Well-known examples of algorithms are the advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) algorithms published by the American Heart Association.

Practice Guideline

A practice guideline is usually developed and written by a team of experts representing professional organizations (e.g., AACN, Society of Critical Care Medicine, American College of Cardiology) or a governmental agency to provide recommendations to care providers. Recommendations are given for managing care and treatments for specific diseases and are based on research or expert opinions.32 Practice guidelines are generally written in text prose, rather than in the flowchart format of algorithms. Practice guidelines are used as resources in formulating the pathway or algorithm. An example is a ventilator-associated pneumonia clinical practice guideline that was developed with major implications for nursing practice: head-of-bed elevation, hand hygiene, oral care, glove use, and ventilator tubing condensate removal.33

Protocol

A protocol is a common tool in research studies. Protocols are more directive and rigid than pathways or guidelines, and providers should not vary from a protocol. Patients are screened carefully for specific entry criteria before being started on a protocol. The many national research protocols include those for cancer and chemotherapy studies. Protocols are helpful when built-in alerts signal the provider to potentially serious problems. Computerization of protocols assists providers in being more proactive regarding dangerous drug interactions, abnormal laboratory values, and other untoward effects that are preprogrammed into the computer.

Quality, Safety, and Regulatory Issues in Critical Care

Patient safety has become a major focus of attention for health care consumers, as well as providers of care and administrators of health care institutions. The Institute of Medicine publication Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century has been the impetus for debate and actions to improve the safety of health care environments. In this report, information and details were given indicating that health care harms patients too frequently and routinely fails to deliver its potential benefits.34 Oftentimes, the definitions of medical errors and approaches to resolving patient safety issues differ among nurses, physicians, administrators, and other health care providers.35

Patient safety has been described as an ethical imperative, and one that is inherent in health care professionals’ actions and interpersonal processes.36 In critical care units errors may occur because of the hectic, complex environment, where there is little room for error and safety is essential.37 In this environment, patients are particularly vulnerable because of their compromised physiological status, multiple technological and pharmacological interventions, and multiple care providers who frequently work at a fast pace. It is essential that care delivery processes that minimize the opportunity for errors are designed and that a “safety culture” rather than a “blame culture” is created.38,39 When an injury or inappropriate care occurs, it is crucial that health care professionals promptly give an explanation of how the injury or mistake occurred and the short- or long-term effects to the patient and family. They should be informed that the factors involved in the injury will be investigated so that steps can be taken to reduce or prevent the likelihood of similar injury to other patients.

The Joint Commission has approved 2010 National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs)40 that are to be implemented in health care organizations (Box 1-2).

The Safe Medical Device Act (SMDA) requires that hospitals report serious or potentially serious device-related injuries or illness of patients and/or employees to the manufacturer of the device, and if death is involved, to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In addition, implantable devices must be documented and tracked.41 This reporting serves as an early warning system so that the FDA can obtain information on device problems. Failure to comply with the act will result in civil action.

It has been shown that intimidating and disruptive clinician behaviors can lead to errors and preventable adverse patient outcomes. Verbal outbursts, physical threats, and more passive behaviors such as refusing to carry out a task or procedure are all under this category. Unfortunately, these types of behavior are not rare in health care organizations, with as many as 40% of clinicians having said that they were involved in such interactions. If these behaviors go unaddressed, it can lead to extreme dissatisfaction, depression, and turnover. There are also systems issues that lead to or perpetuate these situations, such as push for increased productivity, financial constraints, fear of litigation, and embedded hierarchies in the organization.43

Technologies are both a solution to error-prone procedures and functions, and another potential cause for error. Consider bar-code medication administration procedures, multiple bedside testing devices, computerized medical records, bedside monitoring, computerized physician order entry (CPOE), and many others now in development. Each in itself can be a great assistance to the clinician, but must be monitored for effectiveness and accuracy to ensure the best in outcomes as intended for specific use.44

Medication administration continues to be one of the most error-prone nursing interventions for the critical care nurse. Many medication errors are related to system failures, specifically distraction as a major factor. Various interventions have been created in an attempt to decrease medication errors. Most recently, a published study reported establishing a “no interruption zone” for medication safety in an intensive care unit. In this pilot study, there was a 40% decrease in interruptions from the baseline measurement. Although researchers questioned the feasibility of sustaining this decrease in interruptions in the future,45 this is an example of an approach to increase medication safety in the critical care unit.

Privacy and Confidentiality

A landmark law was passed to provide consumers with greater access to health care insurance, promote more standardization and efficiency in the health care industry, and protect the privacy of health care data.42 The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) has created additional challenges for health care organizations and providers because of the stringent requirements and additional resources needed to meet the requirements of the law. Most specific to critical care clinicians is the privacy and confidentiality related to protection of health care data. This has implications when interacting with family members and others, and the oftentimes very close work environment, tight working spaces, and emergency situations. Clinicians are referred to their organizational policies and procedures for specific procedures for their organizations.

Healthy Work Environment

The health care environment is stressful, and increasing challenges in the areas of financial constraints, regulatory requirements, consumer scrutiny, quickly changing technologies and treatment regimens, and workforce diversity contribute to conflicts and difficulties on a daily basis. In this environment, it is essential to offer support for health care providers that can mitigate these challenges and ensure a healthy place to work.

There is an increasing amount of evidence that unhealthy work environments lead to medical errors, suboptimal safety monitoring, ineffective communication among health care providers, and increased conflict and stress among care providers. Synthesis of research in the area of work environment has demonstrated that a combination of leadership styles and characteristics contributes to the development and sustainability of healthy work environments.46

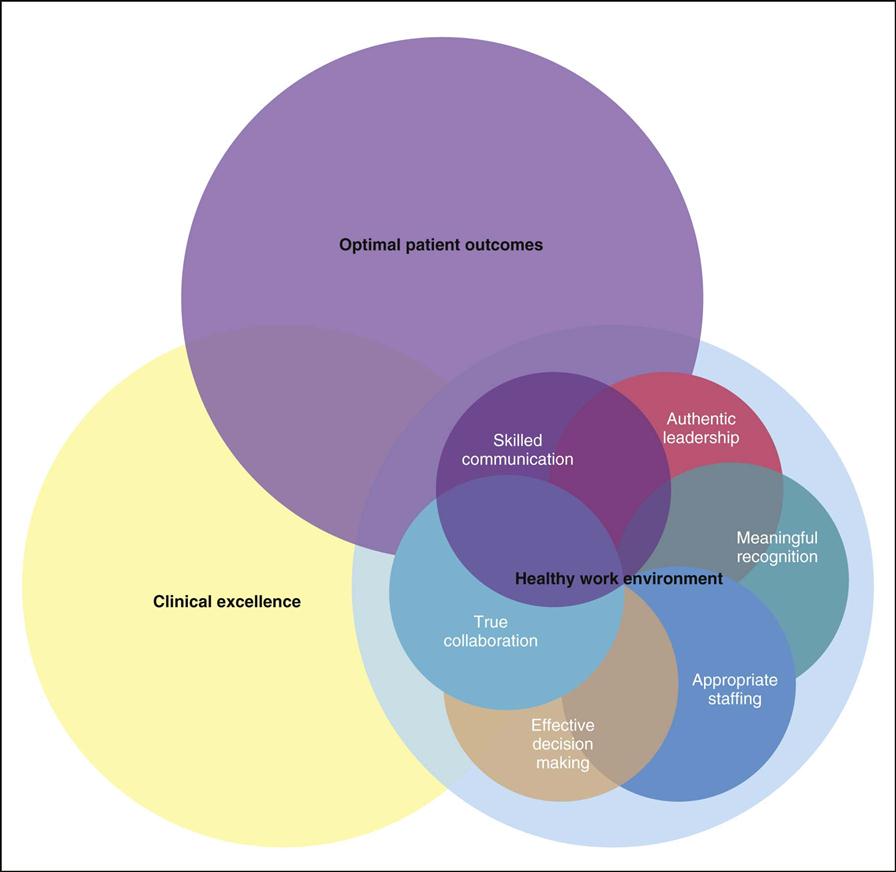

The AACN has formulated standards for establishing and sustaining healthy work environments (HWE). The intent of the standards is to promote creation of environments that will have a positive impact on nursing and patient outcomes. Evidence-based and relationship-centered principles were used to create the standards of professional performance. A summary of the six standards is provided in Box 1-3. Figure 1-1 illustrates the interdependence of each standard, and the ultimate impact on optimal patient outcomes and clinical excellence.

Everyone has a role in creating and sustaining a healthy work environment. Although the manager has a major role in establishing the culture, it is the staff who greatly impact the culture by mentoring new staff, role modeling behaviors, and leading interdisciplinary teams. It is this peer pressure that has the most impact on all other staff.47 Bylone discussed her experience of talking with many staff members about how they think that they can influence the work unit culture. She recommends asking themselves how they influence each of the HWE standards, thus making it a personal experience and journey in achieving the HWE.48 Kupperschmidt and colleagues posed a five-factor model for becoming a skilled communicator: 1) becoming aware of self-deception; 2) becoming authentic; 3) becoming candid; 4) becoming mindful; and 5) becoming reflective; all of which leads to being a skilled communicator, thus creating a healthy work environment.49