39 Care of the thyroid and parathyroid surgical patient

Bilateral Subtotal Thyroidectomy: Removal of most of the thyroid tissue in both lobes with a small remnant of thyroid tissue left at the back portion of the thyroid to protect the parathyroid glands and prevent recurrent laryngeal nerve damage (a potential complication associated with total thyroidectomy).

Parathyroidectomy: Excision of one or more diseased parathyroid glands.

Subtotal/Partial Thyroidectomy: Removal of the thyroid gland with the exception of a small portion retained on the opposite side of the thyroid.

Thyroidectomy: Total excision of the thyroid gland with the parathyroid glands left intact. Normally, a total thyroidectomy is only performed in patients with medullary malignant disease, because total thyroidectomy renders the patient immediately unable to produce any thyroid hormone, thus requiring thyroid hormone supplementation for the remainder of the patient’s life. Patients who are not a candidate for radioablation may also be considered for thyroidectomy.

Thyroid Lobectomy with Isthmusectomy: Removal of one lobe of the thyroid and the isthmus that connects the two lobes.

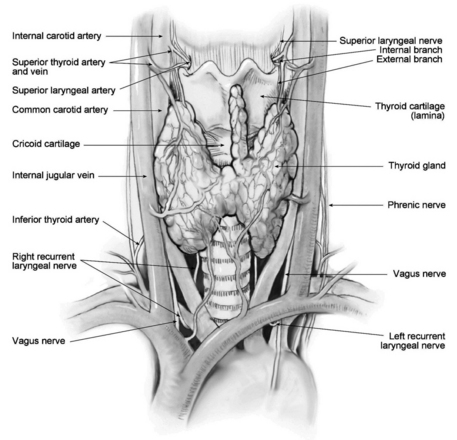

Surgery of the thyroid gland was first performed around ad 500, and the first successful removal of a goiter occurred in ad 1000. By the 1800s, numerous thyroidectomies had been performed; however, nearly half of the patients died after surgery as a result of tetany. This morbidity rate was secondary to the removal of the parathyroid glands, whose function was not well understood at the time. In the early 1900s, a greater understanding of the role of the parathyroid glands promoted the subtotal thyroidectomy procedure which significantly reduced postoperative complications. In the late 1990s, endoscopic and minimally invasive techniques further reduced some postoperative complications and expanded the number of outpatient cases performed. The type of thyroid surgical procedure chosen depends on the patient’s age, tumor cell type and size, presence of an encapsulated or extracapsular tumor, and any invasion of adjacent structures (Fig. 39-1).

FIG. 39-1 Thyroid gland and surrounding anatomic structures.

(From Elisha S, et al: Anesthesia case management for thyroidectomy, AANA J 78(2):152, 2010.)

Anesthesia

Surgery on the thyroid and parathyroid glands is commonly performed with general anesthesia. Regional and local techniques, such as a cervical plexus blockade, are growing in popularity as minimally invasive techniques and the number of outpatient cases grows.1–3 Appropriate postoperative care for a patient receiving general anesthesia is instituted in the postanesthesia care unit. Minimally invasive techniques and those procedures performed with regional or local anesthesia may minimize the recovery requirements for this patient population.

Perianesthesia nursing care

Pain management

Pain may be minimal after thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy when performed on an outpatient basis. Postoperative analgesia requirements are greater in the open procedure population. Small doses of an opioid may be needed in the first 24 hours for patients admitted to a facility. Severe pain is an abnormal finding that can indicate unexpected bleeding or nerve damage, and it is a risk factor for unwanted hypertension.

Dressings and drains

Postoperative dressings are small, and drains are generally not required. Postoperative drainage is minimal and should not visibly soak through the dressing. Some disagreement persists regarding the use of surgical drains. There are questions regarding whether the presence of a drain causes increased pain, scarring, cost, length of stay, and a drain’s limited ability to identify and prevent hematoma.4,5 Drains may be indicated in the presence of greater intraoperative blood loss or an extensive procedure or when a large space is left after removal of a tumor or goiter.

Complications

Hypoparathyroidism and hypocalcemia

The assessment of any patient who verbalizes tingling symptoms includes testing for the presence of Chvostek sign (the development of a lip twitch or facial spasm when the cheek is tapped over the facial nerve) and Trousseau sign (carpal spasm development when a blood pressure cuff is applied and the circulation transiently occluded). Laboratory findings, Chvostek sign, and an evaluation of carpopedal spasms (clonus in the feet when dorsiflexed) are preferred over assessing for Trousseau sign, which can sometimes be painful. Definitive treatment involves intravenous administration of calcium. Although both calcium chloride and calcium gluconate may be used, calcium gluconate is preferred for its greater bioavailability and lesser arrhythmogenic potential. When intravenous calcium is administered, it is given via slow push with continuous electrocardiographic monitoring performed before, during, and after the infusion. Early and routine calcium and vitamin D supplementation have been indicated as a useful strategy in the reduction of hypocalcemic complications.6–8

Infection

Disagreement exists about the need for routine antibiotic administration, because the incidence of postoperative infection in patients who have undergone thyroid and parathyroid surgery is rare.9 Any postoperative infection symptoms should be investigated and treated with appropriate antibiotic therapy and wound care.

Summary

Postoperative nursing assessment should focus on the potential for cardiopulmonary compromise owing to sympathetic output related to a hyperthyroid state, hemorrhage, and venous oozing or laryngeal edema. The nurse should proactively address pain management, proper positioning to minimize suture line stress, ongoing assessment of the operative dressing and intake and output status. Although rare, thyroid surgery complications can include inferior or superior laryngeal nerve damage with possible vocal cord paralysis, laryngeal stridor, airway and respiratory compromise, bleeding that causes cervical or neck hematoma requiring surgical evacuation, hypocalcemia, tetany, seizures and mental disturbances, thyroid storm, and infection. Recognition of potential complications and implementation of appropriate and rapid treatment interventions are essential for an optimal postoperative outcome.

1. Suri KB, et al. Postoperative recovery advantages in patients undergoing thyroid and parathyroid surgery under regional anesthesia. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010;14:49–50.

2. Tuggle CT, et al. Same-day thyroidectomy: A review of practice patterns and outcomes for 1,168 procedures in New York State. Ann Surg Oncol.2011;18:1035–1040.

3. Elisha S, et al. Anesthesia case management for thyroidectomy. AANA J. 2010;78:151–160.

4. Dunlap WW, et al. Thyroid drains and postoperative drainage. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 143. 2010:235–238.

5. Morrissey AT, et al. Comparison of drain versus no drain thyroidectomy: Randomized prospective clinical trial. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.2008;37:43–47.

6. Roh JL, et al. Prevention of postoperative hypocalcemia with routine oral calcium and vitamin D supplements in patients with differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma undergoing total thyroidectomy plus central neck dissection. Cancer. 2009;115:251–258.

7. Roh JL, Park CI. Routine oral calcium and vitamin D supplements for prevention of hypocalcemia after total thyroidectomy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:675–678.

8. Sabour S, et al. The role of rapid PACU parathyroid hormone in reducing post-thyroidectomy hypocalcemia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:727–729.

9. Moalem J, et al. Patterns of antibiotic prophylaxis use for thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy: Results of an international survey of endocrine surgeons. J Am Coll Surg.2010;210:949–956.

AACE/AME Task Force on Thyroid Nodules: American as- sociation of clinical endocrinologists and associazione medici endocrinologi medical guidelines for clinical prac- tice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules, 2020. available at: https://www.aace.com/sites/default/files/ThyroidGuidelines.pdf, March 22, 2012. Accessed

Gal I, et al. Minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy and conventional thyroidectomy: A prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc.2008;22:2445–2449.

Hopkins B, Steward D. Outpatient thyroid surgery and the advances making it possible. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;17:95–99.

Johnson K. Laparoscopic or open removal of parathyroid. Intern Med News. 2005;38:28.

Lee KE, et al. Outcomes of 109 patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma who underwent robotic total thyroidectomy with central node dissection via the bilateral axillo-breast approach. Surgery. 2010;148:1207–1213.

Mazzaferri EL, et al. Practical management of thyroid cancer: A multidisciplinary approach. New York: Springer; 2010.

McKennis A, Waddington C. Nursing interventions for potential complications after thyroidectomy. available at www.sohnnurse.com/thyroidectomy.html

Muenscher A, et al. The endoscopic approach to the neck: A review of the literature, and overview of the various techniques. Surg Endosc.2011;25:1358–1363.

Noble KA. Thyroid storm. J Perianesthesia Nurs. 2006;21:119–125.

Oertli D, Udelsman R. Surgery of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. New York: Springer, 2007.

Patel M, et al. Fibrin glue in thyroid and parathyroid surgery: Is under-flap suction still necessary. Ear Nose Throat J.2006;85:530–532.

Takesuye D, et al. Practice analysis: Techniques of head and neck surgeons and general surgeons performing thyroidectomy for cancer. Qual Manage Health Care.2006;15:257–262.