52 Care of the substance-using patient

Alcoholic: A person who is excessively dependent on alcohol and who has a noticeable degree of mental, physical, psychologic, or pathologic disorders.

Alcoholic Cirrhosis (Laënnec’s Cirrhosis): A fibrotic form of cirrhosis precipitated by alcohol abuse.

Anterograde Amnesia: The inability to form new memories or recall events that occur after the onset of the amnesia.

Delirium Tremens: An acute and sometimes fatal psychotic reaction caused by cessation of excessive intake of alcoholic beverages over a long period of time.

Endocarditis: Inflammation of the endocardium and heart valves.

Hallucinations: A sensory perception that does not result from an external stimulus and that occurs in the waking state.

Plasma Cholinesterase: An enzyme in the blood plasma that acts as a catalyst in the hydrolysis of acetylcholine to choline and acetate.

Potentiated: A synergistic action in which the effect of two drugs given simultaneously is greater than the sum of the effects of each drug given separately.

Sensorium: The part of the consciousness that includes the special sensory perceptive powers and their central correlation and integration in the brain. A clear sensorium conveys the presence of a reasonably accurate memory together with spacial orientation.

Substance Abuse: The overuse of stimulant, depressant, or other chemicals or drugs that is detrimental to the patient’s physical or mental health.

Substance Dependence: The total psychophysical state of one addicted to drugs or alcohol who must receive an increasing amount of the substance to prevent the onset of withdrawal symptoms.

Substance Use: A maladaptive pattern of the use of a drug, chemical, or biologic entity that is capable of being abused because of its physiologic or psychologic effects.

Substance abuse is the major public health issue in America. More than 25 million Americans have used illicit drugs on a monthly basis, and more than 80% of all the opioids in the world are probably used primarily in the United States.1–5 Add to this the fact that the abuse of prescription drugs has become a major contributing factor to the increase in the use of illicit drugs. Consequently, the significant increase in the number of persons who use opioids, amphetamines, cocaine, hallucinogens, barbiturates, and date rape drugs has created new problems in today’s perianesthesia nursing care. One in five patients in the perioperative area has an alcohol use disorder, one in three patients has a nicotine use disorder, and one in 10 patients has a drug use disorder.6

Drug dependence is the nonmedical use of a drug and consists of the self administration of any drug in a manner that deviates from the approved medical or social practices within a given culture.5 Physical dependence is an altered physiologic state caused by repeated administration of a drug that necessitates the continued administration of the drug to prevent the appearance of withdrawal or abstinence syndromes characteristic for that drug. Psychologic dependence is habituation-compulsive drug use. In this type of dependence, a drug is used to alter mood and feeling. Eventually, dependent people come to believe that the effects of the drug are necessary to maintain an optimal state of well being. Another term that should be defined in discussions of substance dependence is tolerance. Drug tolerance is a state in which, after repeated administration of a drug, a given dose produces a decreased effect or in which increasingly larger doses are needed to obtain the same effect as that of the original dose.

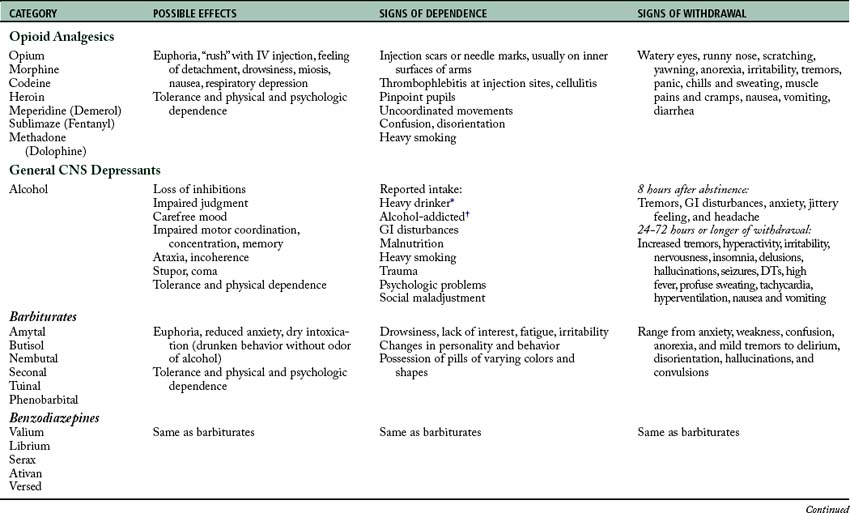

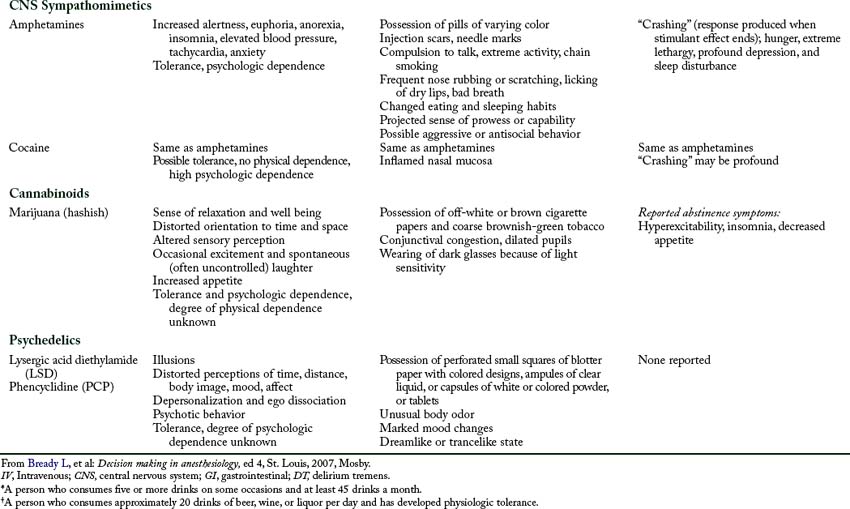

The pharmacologic agents that are most commonly seen in dependence can be grouped as follows: (1) opioid analgesics; (2) general central nervous system (CNS) depressants, such as alcohol and barbiturates; (3) CNS sympathomimetics, such as amphetamines and cocaine; (4) cannabinoids, such as marijuana; and (5) psychedelics (of which lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and phencyclidine are the prototypic drugs; Table 52-1), inhalants, club drugs, and date rape drugs.

Opioid analgesics

Opioid analgesics cause strong psychological dependence. Physical dependence is manifested by the withdrawal syndrome of autonomic storm and CNS irritability. A strong tolerance for these drugs and a cross tolerance with other drugs of the same classification of opioid analgesics develop. Studies indicate that in people who are chronically addicted to opioid analgesics such as morphine, the minimum alveolar concentration of inhalation anesthetics (see Chapter 20) is increased, which indicates that a cross tolerance with general inhalation anesthetics may exist.7,8

Perianesthesia nursing care of a patient who is dependent on an opiate, such as heroin dependency, focuses on monitoring the patient for complications.3 Monitoring for the withdrawal (abstinence) syndrome is the foremost concern. The abstinence syndrome after dependence on an opiate occurs in two phases. The acute phase occurs during the first few days. The protracted phase, which is not readily treatable, can persist for as long as 2 to 6 months. The acute opiate abstinence phase is not dangerous to life because it usually is not associated with convulsions and delirium. Instead, the symptoms are anxiety, nervousness, jittery behavior, anorexia, rhinorrhea, hypotension, muscle twitching, insomnia, sweating, pupillary dilation, gooseflesh, nausea, and vomiting. Symptoms during the protracted phase include those of the acute phase, along with convulsions and delirium. Treatment for the acute opiate abstinence phase is accomplished with any opioid analgesic; reports indicate that clonidine has proved to be most effective in attenuating the symptoms. New research indicates that dexmedetomidine may also be effective in attenuating the symptoms. Treatment for the protracted phase focuses on protection of the patient and abatement of the symptoms shown by the patient. If a patient is suspected of dependence on an opiate, opioid antagonists such as naloxone (Narcan) should not be administered because the withdrawal syndrome can be precipitated. No attempt should be made at withdrawal of the patient who is actively dependent on an opiate during the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) period. Liberal use of morphine or methadone in the PACU appears to be satisfactory. Patients who are formerly dependent on opioids should not receive opioids; analgesics such as pentazocine (Talwin) and butorphanol (Stadol) should be used in their place. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs may also be considered in a multimodal approach for these patients.6

General central nervous system depressants

The dependency rate of persons taking benzodiazepine compounds has increased significantly during the last decade. The benzodiazepine drug is usually taken in combination with marijuana or alcohol to obtain a high. Chronic intoxication has been reported with the use of these compounds. The benzodiazepine that produces the most dependency is diazepam (Valium); however, midazolam (Versed) will soon rank at the same level as diazepam. These drugs are becoming popular because of their rapid onset of action coupled with their pleasure-giving effects. The pharmacologic effects of the benzodiazepines are similar to those of the barbiturates.9 This classification of drugs is somewhat addictive and includes withdrawal syndromes.

For treatment of mild to moderate overdoses of benzodiazepines, the drug physostigmine in an adult dosage of 1 to 2 mg given intravenously can be used. Flumazenil (Romazicon), is a true benzodiazepine receptor antagonist with longer action and fewer side effects. The usual adult dose is 0.1 to 0.2 mg given intravenously. As with naloxone for patient dependence on an opioid, flumazenil must be used with caution with patients who are benzodiazepine dependent. More specifically, reversal of benzodiazepine dependence is associated with precipitating the withdrawal syndrome, including seizures (see Chapter 21).

Alcoholism has long been widespread, but it is difficult to define. An alcoholic, for the purposes of this discussion, is a person who is excessively dependent on alcohol and who has developed a noticeable degree of mental, physical, psychologic, or pathologic disorders. Alcohol was the first anesthetic; it can produce anesthesia, respiratory depression, and hypotension. Alcoholic dependency has been linked to complications during the perianesthesia phase including alcohol withdrawal syndrome, increased infections, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cardiovascular complications, and secondary hemorrhage.6

Alcohol affects many of the body’s major systems.10 Cirrhosis of the liver is common in the later stages of alcoholism. This knowledge is of importance to the perianesthesia nurse because the liver detoxifies many drugs administered during the perioperative period (see Chapter 16). Hepatic cirrhosis can produce significant alterations in pulmonary and cardiovascular functions. Hyperventilation and arterial oxygen desaturation are common findings caused by an increase in shunting of blood away from areas in the lung where diffusion of oxygen occurs. Concomitant with this is an increase in blood volume that can lead to cardiac hypertrophy and eventually to congestive heart failure. Fluid balance is affected by the presence of alcohol, because alcohol exhibits antidiuretic effects by inhibiting the release of antidiuretic hormone. Alcoholic cirrhosis (Laënnec’s cirrhosis) is also associated with portal vein hypertension, renal failure, hypoglycemia, duodenal ulcer, esophageal varices, and hepatic encephalopathy.

In approximately 5% of the alcoholic population, the severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome, or delirium tremens, occurs with abrupt cessation of alcohol ingestion. The mortality rate from this syndrome is approximately 15%; it is considered a medical emergency. The time of onset of delirium tremens is 48 to 72 hours after the abrupt discontinuation of alcohol ingestion.11

Central nervous system sympathomimetics

Cocaine has a two-pronged effect—vasoconstriction and mood alteration—because it inhibits the reuptake of catecholamines.9,12 The mood-altering effect is similar to the psychological effect produced by amphetamines. Cocaine is steadily becoming one of the most popular drugs among persons dependent on a substance. Patients who are known to be dependent on cocaine should be closely monitored in the PACU for hypertension and cardiac arrhythmias. These patients are prone to nosebleeds, and care should be taken in giving nursing care near or directly to the nose and nasal cavity.

Cannabinoids

The hemp plants, for which cannabis is the generic name, contain approximately 30 active substances that are called cannabinoids. Of these, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the most active. Marijuana is the generic term applied to the hemp plants. The marijuana cigarette contains rolled or crushed dried leaves from the hemp plant. Each marijuana cigarette contains approximately 0.005 g of THC. The cannabinoids are threefold more potent when inhaled than when ingested orally. Psychological changes occur minutes after inhalation of marijuana, and the effects peak in 1 hour for as long as 3 hours.3

The peripheral effects of THC on the autonomic nervous system include vagal blockade and beta-adrenergic stimulation. The person dependent on marijuana has tachycardia, peripheral vascular dilation, bronchodilation, conjunctival congestion, and a dry mouth. The actual effects of THC on the CNS are not known.13

Psychedelics

Phencyclidine is the hallucinogen most commonly used today. This drug is a popular veterinary anesthetic agent (Sernylan) and is related pharmacologically to the drug ketamine. It can be ingested, taken parenterally, or inhaled. The sensory effects have a rapid onset and last approximately 1 to 2 hours, and the CNS effects can last for 1 or more days. The CNS activation usually produces sympathetic nervous system activation.14

The primary focus of perianesthesia nursing care for the patient who is in the hallucinogenic state is to prevent self injury and sedation. The bad trip effects can be managed with a phenothiazine or benzodiazepine such as diazepam. Other considerations in regard to the patient who has ingested LSD are that the analgesic effects of opioids are potentiated by LSD and that the plasma cholinesterases are somewhat inhibited by LSD. Opioid dosage may need to be reduced in these patients, and if succinylcholine is to be administered to the patient, the possibility of prolonged apnea exists (see Chapter 23).

Inhalants

Inhalants can make a person extremely dependent and consist of breathable chemical vapors that produce mind-altering effects. Persons who use inhalants can have significant dependence; they are likely to be teenage people because the drugs are easily accessible and inexpensive.14,15 Inhalants are classified into three categories: solvents, gases, and nitrates.

The solvents consist of paint thinners or solvents, electronic contact cleaners, and felt-tip marker fluid. The gases consist of such household products and commercial products as butane lighters and propane tanks, whipping cream aerosols, spray paints, hair or deodorant sprays, and fabric protector sprays. Gases used for anesthetic medical purposes, such as isoflurane, sevoflurane, desflurane, and nitrous oxide (see Chapter 20), are now being used illicitly and can cause dependency.16 The nitrates—such as cyclohexyl nitrite and butyl nitrite, which are available to the public, and amyl nitrite, which is only available by prescription—are now used as substances that can produce dependency.

The inhalants that cause dependency produce effects that are similar to the inhalational anesthetics as described in Chapter 20. Basically, these inhalants cause an intoxicating effect when they are inhaled through the nose or mouth into the lungs. When inhaled in high concentrations, these inhalants can induce heart failure and even death. Some of the irreversible effects of these inhalants can include hearing loss, peripheral neuropathies or limb spasms, central nervous system damage, and bone marrow damage. Some of the serious yet potentially reversible effects include hemoglobin oxygen depletion and liver or kidney damage.17

Club drugs

Club drugs are most popular in the teenage and young adult population who are part of the nightclub, bar, rave, or trance scenes. Raves and trance parties are usually nightlong events that include adolescents who might not use the specific drugs; however, those who do are attracted to the use of these rather low-cost agents that appear to produce increased stamina and intoxicating highs. Research now shows that these drugs can change critical parts of the brain. Because of the different effects on the E-C coupling mechanisms of muscles as opposed to skeletal muscle relaxants (see Chapter 23), these agents are not implicated in malignant hyperthermia (see Chapter 53).

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, or ecstasy) is a psychoactive drug that has both stimulant (amphetamine-like) and hallucinogenic (LSD-like) properties. This drug has many street names such as ecstasy, Adam, XTC, hug, beans, and love drug. MDMA has many routes of administration, including oral, rectal, intravenous, or inhalation.18

The problems associated with MDMA are similar to those found with the use of amphetamines and cocaine, which were discussed previously. The psychological difficulties may include such phenomena as confusion, depression, sleep problems, severe anxiety, and paranoia. The physical difficulties include such things as muscle tension, involuntary teeth clenching, nausea, blurred vision, faintness, and chills or sweating. Physiologic concerns are that this category of drugs can cause hypertension and tachycardia, and long-term use can result in damage to the brain in the parts that focus on thought, memory, and pleasure.

Date rape drugs

Ketamine is an intravenous anesthetic drug (see Chapter 21) that is used illegally in the club and rave scenes and has been used as a date rape drug. It can be injected or snorted and is known on the street as special K or vitamin K. This drug produces a dreamlike state and hallucinations.18 In high doses, ketamine causes delirium, amnesia, impaired motor function, high blood pressure, depression, and apnea. The veterinary form of this drug appears to create the most dependency; its frequency of use is steadily increasing.

Care of the substance abuse patient in the postanesthesia care unit

The use of illicit drugs has become a national issue, particularly in the health care arena. It is even a greater issue for the health care providers in the perianesthesia nursing setting. The recreational drugs, such as alcohol, along with the many other illicit drugs such as cannabis, “crack,” LSD, cocaine, and amphetamines present a significant challenge to the PACU nurse. Many of these patients that abuse drugs can have a “normal” anesthetic experience and then experience acute drug withdrawal in the PACU. If a patient exhibits increased blood pressure, tachycardia, abdominal cramping, irritability, tremors, diarrhea, or sweating, acute drug withdrawal should be suspected. The patient should be examined for the signs and symptoms as described in Table 52-2. After the evaluation is performed, the PACU nurse should notify the attending physician or anesthetist to facilitate the appropriate intervention. The treatment should be symptom oriented, and use of scoring systems to determine treatment approach is becoming more prevalent.6 In addition, the emergency drugs and equipment should be placed at the patient’s bedside. Other interventions will probably include a blood sample and a urine sample to aid in the identification of the specific drug in question.

Table 53-2 Initial Patient Evaluation for Suspected Substance Abuse

| EVALUATION FOCUS | EVIDENCE OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE |

|---|---|

Adapted from Nagelhout J, Plaus K: Nurse anesthesia, ed 4, St. Louis, 2010, Saunders.

Implications for practice

If anesthesia providers underestimate the prevalence of ISU, we can assume that perianesthesia nurses in the preoperative assessment areas also underestimate use. Preoperative assessment clinics provide an appropriate setting for interventions regarding ISU, determining high-risk behavior, and effective strategies to institute lifestyle changes. Perianesthesia nurses in the preoperative setting should consider the use of a structured computerized self-assessment questionnaire about ISU with the goal of increased recognition and decreased perioperative risks for the patient.

Source: Kleinwächter R, et al: Improving the detection of illicit substance use in preoperative anesthesiological assessment, Minerva Anestesiol 76:29–37, 2010.

Summary

Health care practitioners must recognize the severity of the addiction trends among subsets of health care professions.4 It is important to learn to recognize, report, and prevent this continued escalation of drug dependence. The key feature is that all must agree that early intervention may save the lives of colleagues and fellow practitioners. Probably the most difficult abuse issue that has become of national epidemic is the abuse of prescription drugs. This problem presents the PACU nurse with a variety of signs and symptoms that are difficult to explain or justify. However, if the patient demonstrates abnormal physiologic function, prescription drug abuse should be considered.

The intent of this chapter was to provide the reader with an overview of the many drugs and substances that can be used by a person to become dependent. Not all the drugs and substances were identified or discussed because this area is ever changing. The key point presented was the overview of how the perianesthesia practitioner should modify the PACU nursing care with regard to patients who are dependent on a drug or substance category presented. Armed with this knowledge, the outcomes of the perianesthesia patient are enhanced. Certainly the use of illicit drugs is an ever increasing public health issue. In the PACU, drug withdrawal can and does occur. Identification of the specific abused drug is essential, and rapid intervention can be life saving for this type of patient.

1. Conlay L, et al. Case files anesthesiology. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011.

2. Frost E, Seidel M. Preanesthetic assessment of the drug dependent patient. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. 1990;8(4):829–842.

3. Kaye A, et al. Perioperative anesthesia clinical considerations of alternative medicines. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2004;22:125–139.

4. Luck S, Hedrick J. The alarming trend of substance abuse in anesthesia providers. J Perianesth Nurs. 2004;19(5):308–311.

5. Manchikanti L. National drug control policy and prescription drug abuse: facts and fallacies. Pain Physician.2007;10:399–424.

6. Kork F, et al. Perioperative management of patients with alcohol, tobacco and drug dependency. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2010;23:384–390.

7. Mitra S, Sinatra R. Perioperative management of acute pain in the opioid-dependent patient. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:212–227.

8. Miller R, Pardo M. Basics of anesthesia, ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2011.

9. Fisher L. Anesthesia and uncommon diseases, ed 5. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

10. Atlee J. Complications in anesthesia, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

11. Huckabee M. Perioperative care of the active substance dependent. J Post Anesth Nurs. 1988;3(4):254–259.

12. Longnecker D, et al. Anesthesiology. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2007.

13. Kurtzman T, Otsuka K. Inhalant dependent by adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2000;28(3):170–180.

14. Nagelhout J, Plaus K. Nurse anesthesia. ed 4. St. Louis: Saunders; 2010.

15. Davis P, et al. Smith’s anesthesia for infants and children. ed 8. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011.

16. Stoelting R. Pharmacology and physiology in anesthetic practice, ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005.

17. Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. Am J Addict. 2001;10(1):79–94.

18. Morgan M. Ecstasy (MDMA): a review of its possible persistent psychologic effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl).2000;152(3):230–248.

AACN. Core curriculum for progressive care nursing. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

Aitkenhead A, et al. Textbook of anesthesia, ed 5. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.

Alspach J. Core curriculum for critical care nursing, ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.

Barash P, et al. Clinical anesthesia, ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

Barrett K, et al. Ganong’s review of medical physiology, ed 23. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009.

Bready L, et al. Decision making in anesthesiology, ed 4. St. Louis: Mosby; 2007.

Brunton L, et al. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, ed 12. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2010.

Drake R, et al. Gray’s anatomy for students, ed 2. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

Deutschman C, Netigan P. Evidence-based practice of critical care. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

Hall J. Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology, ed 12. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2011.

Hines R, Marschall K. Handbook for Stoelting’s anesthesia and co-existing disease, ed 3. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.

Kaplan J, et al. Cardiac anesthesia. New York: Churchill Livingstone.; 2011.

Miller R, et al. Miller’s anesthesia, ed 7. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

Pasero C, McCaffery M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011.

Rogers E. Postanesthesia care of the cocaine dependent. J Post Anesth Nurs. 1991;6(2):102–107.

Sandberg W, et al. The MGH textbook of anesthetic equipment. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2011.

Schick L, Windle PE. Perianesthesia nursing core curriculum: perianesthesia nursing core curriculum. ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

Schirle L. Polyuria with sevoflurane administration: a case report. AANAJ.2011;79(1):47–50.

Shorten G, et al. Postoperative pain management: an evidence-based guide to practice. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006.

Teter C, Guthrie S. A comprehensive review of MDMA and GHB: two common club drugs. Pharmacotherapy.2001;21(12):1486–1513.

Townsend C, et al. Sabiston’s textbook of surgery, ed 18. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008.

Vincent J, et al. Textbook of critical care, ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2011.

White P. Perioperative drug manual, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.

Weiss S. Anesthesia for the alcoholic and addict. AANA J. 1979;47(3):309–312.