54 Care of the shock trauma patient

Compartment Syndrome: A pathologic condition caused by the progressive development of arterial compression and consequent reduction of blood supply.

Damage Control Resuscitation: A systematic approach to control bleeding at the point of injury by definitive treatment interventions of minimizing blood loss and maximizing tissue oxygenation.

Injury: A state in which a patient experiences a change in physiologic or psychological systems.

Microvascular: Pertaining to the portion of the circulatory system that is composed of the capillary network.

Motor Vehicle Crash (MVC): Occurs when a vehicle collides with another vehicle or object and can result in injuries or death.

Pattern of Injury: The circumstance in which an injury occurs, such as causation from sudden deceleration, wounding with a projectile, or crushing with a heavy object.

Permissive Hypotension: A guided intervention that limits fluid resuscitation until hemorrhage is controlled.

Primary Assessment: The first in order of importance in the evaluation or appraisal of a disease or condition.

Resuscitation: Use of emergency measures in an effort to sustain life.

Secondary Assessment: Evaluation of a disease or condition with previously compiled data.

Shock: An abnormal condition of inadequate blood flow and nutrients to the body’s tissues, with life-threatening cellular dysfunction.

Shock Trauma: A sudden disturbance that causes a wound or injury and results in acute circulatory failure.

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS): Inflammatory disturbance that affects multiple organ systems of the body.

Trauma: Tissue injury, such as a wound, burn, or fracture, or psychological injury in which personality damage can be traced to an unpleasant experience related to tissue injury, such as a wound, burn, amputation, or fracture.

Shock trauma care continues to change dramatically in response to innovative surgical technologies, advancements in anesthesia agents, and trauma research. Likewise, the medical advances continue to be driven by the state of the trauma science directly resulting from military medicine’s evolving combat casualty management from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In peacetime, the civilian trauma centers take the lead in timely research and evidence-based medicine to establish new trauma protocols and to translate the trauma research to the practice at the bedside. However, in wartime, it is military medicine’s combat medical research and scientific data outcomes that guide the cutting edge benefiting civilian trauma centers.1 The history of advancements in shock trauma care is directly linked to wars and the military’s battlefield medicine.1 Trauma care continues to advance in the twenty-first century with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Permissive hypotension and damage control hemorrhage bring new dimensions in treating severe hemorrhagic shock. Consequently, the treatment of shock is now focused on rapid transport and guided resuscitation within the “golden hour.”2 Advances in vascular surgery have led to better patient outcomes. Today, the battlefields in Iraq and Afghanistan have continued to advance shock trauma nursing care that directly correlates with enhance trauma patient outcomes.

Epidemiology of trauma

In the United States, trauma injuries continue to be the fourth leading cause of death, affecting the lives of more than 70 million people each year.3–7 Furthermore, trauma accounts for more deaths in the United States during the first four decades of life than any other disease. Surprisingly, fatality rates for older adults are now higher than rates for younger adults.5,6 Mortality from trauma is the tip of the iceberg, a small indication of a much bigger problem; many patients survive trauma, need surgical intervention, and require lengthy rehabilitation.

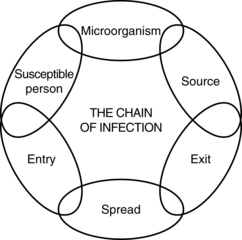

Although 50% of all deaths attributed to trauma occur within minutes to hours after the injury, 30% of patients die within 2 days of neurologic injury; the remaining 20% of deaths occur as a result of complications.3 Overwhelming infection and sepsis result from these traumatic injuries, and trauma patients are at risk for multiple complications, including respiratory, circulatory, neurologic, and renal failure. Numerous pathologic conditions and inflammatory derangements can contribute to this high incidence rate of late mortality from sepsis. Trauma patients who need surgery and anesthesia have greater vulnerability to life-threatening conditions and mandate vigilant, astute postanesthesia nursing care.

Prehospital phase

Mechanism of injury

The pattern or MOI simply refers to the manner in which the trauma patient was injured.8 For accurate assessment of the trauma patient in the PACU, the nurse needs a basic understanding of the different types of MOI. Patterns of injury are related to the categories of the injuring force and the subsequent tissue response. A thorough understanding of these aspects of injury helps in determining the extent and nature of the potential injuries. Damage occurs when the force deforms tissues beyond failure limits.8 Injuries result from different kinds of energy (kinetic forces, such as motor vehicle crashes [MVCs], falls, or bullets) or acute exposure (thermal, chemical, electrical, radiation, or high-yield explosives) to the tissues and underlying structures. Some of the major factors that influence the severity of the injury are the velocity of the objects and the force in terms of physical motion to moving or stationary bodies. The force is the mass of an object multiplied by the acceleration. Numerous studies conclude that the MOI helps identify common injury combinations, predict eventual outcomes, and explain the type of injury sustained.8 Although a certain pattern of injury may be predictable for specific injuries, trauma patients may sustain other injuries. A thorough assessment for identification of all actual and potential injuries is needed.8,9

Various forms of traumatic injuries are: blunt force (high-velocity); penetrating, such as those that cut or pierce; falls from great heights; firearms; and chemical, electric, radiant, and thermal burns. MVCs create impressive forces that can fracture extremities, crush organs, and lead to massive blood loss and soft tissue damage. At the time of a crash, three impacts occur: (1) vehicle to object; (2) body to vehicle; and (3) organs within body. Forces are exerted in relation to acceleration, deceleration, shearing, and compression.8,9 Acceleration-deceleration injuries occur when the head is thrown rapidly forward or backward, resulting in sudden alterations. The semisolid brain tissue moves slower than the solid skull and collides with the skull, causing injury. The injury where the brain makes contact with the skull is called a coup. The brain injury can also occur as the brain tissue is thrown in the opposite direction, causing damage in the contralateral skull surface, which is known as contrecoup injury. Ever-changing MOIs also create the need for new nursing educational programs and competencies for postanesthesia nurses to stay up to date and to advance practice.

Blunt trauma

Blunt trauma is one of the major types of trauma injuries that is best described as a wounding force that does not communicate to the outside of the body. Blunt forces produce crushing, shearing, or tearing of the tissues, both internally and externally.8–10 High-velocity MVCs and falls from great heights cause blunt-trauma injuries that are associated with direct impact, deceleration, continuous pressure, and shearing and rotary forces.8–10 These blunt-trauma injuries are usually more serious and life threatening than other types of trauma because the extent of the injuries is less obvious and diagnosis is more difficult. Because blunt-trauma injuries can leave little outward evidence of the extent of internal damage, the nurse must be extremely vigilant and astute in making observations and ongoing assessments.

When the body decelerates, the organs continue to move forward at the original speed. As the body’s organs move in the forward direction, they are torn from their attachments by rotary and shearing forces.8–10 Furthermore, blunt forces disrupt blood vessels and nerves. This MOI to the microcirculation causes widespread epithelial and endothelial damage and thus stimulates cells to release their constituents and further activates the complement, the arachidonic acid, and the coagulation cascade that activated the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. This unique inflammatory response is covered later in this chapter. Finally, blunt trauma may mask more serious complications related to the pathophysiology of the injury.

Penetrating trauma

Penetrating trauma refers to an injury produced by a foreign object, such as stab wounds and firearms. The severity of the injury produced by a foreign body is related to the underlying structures that are damaged. The MOI causes the penetration and crushing of underlying tissues and the depth and the diameter of the wound that results from penetrating trauma. Tissue damage inflicted by bullets depends on the bullet’s size, velocity, range, mass, and trajectory. Knives often cause stab wounds, but other impaling objects can cause damage. Tissue injury depends on length of the object, the force applied, and the angle of entry. These penetrating wounds cause disruption of tissues and cellular function and thus result in the introduction of debris and foreign bodies into the wound.8,10 Impaled objects are left in place until definitive surgical extraction is available because of the tamponade effect of vascular injuries. Finally, the insult to the body may occur as local ischemia or extend to a fulminant hemorrhage from these penetrating injuries.10

Contusion of tissues

When blunt trauma is significant enough to produce capillary injury and destruction, contusion of tissues occurs. Consequently, the extravasation of blood causes discoloration, pain, and swelling.8–10 If a large vessel ruptures, a hematoma may produce a distinct palpable lesion. With a massive contusion or hematoma, an increase in myofascial pressures often results in sequelae known as compartment syndrome.9,10 A compartment is a section of muscle enclosed in a confined supportive membrane called fascia; compartment syndrome is a condition in which increased pressure inside an osteofascial compartment impedes circulation and impairs capillary blood flow and cellular ischemia, resulting in an alteration in neurovascular function.9,10 This syndrome occurs more frequently in the lower leg or forearm but can occur in any fascial compartment. Damaged vessels in the ischemic muscle dilate in response to histamine and other vasoactive chemical substances, such as the arachidonic cascade and oxygen-free radicals. This dilation, with resultant leakage of fluid from capillary membrane permeability, results in increased edema and tissue pressure.9 The increased edema and pressure compress capillaries distal to the injury, impeding microvascular perfusion. These pathologic changes cause a repetitive cycle within the confined tissues, which increases swelling and leads to increased compartment pressures. Fascial compartment syndrome can be measured if indicated. Normal pressure is more than 10 mm Hg, but a reading of more than 35 mm Hg suggests possible anoxia.11,12 A fasciotomy may be indicated to prevent muscle or neurovascular damage.

Scoring systems

Numerous scoring mechanisms have been designed to assist in measuring the severity of injuries and attempt to forecast morbidities, mortalities, and the likelihood of functional outcomes. Each scoring system is unique and measures the physiologic status of the patient. Some scoring systems work better for penetrating versus blunt trauma.11,12 The PACU nurse may record the injury scoring measurement as initial baseline severity indices; however, accuracy can be limited despite the score.

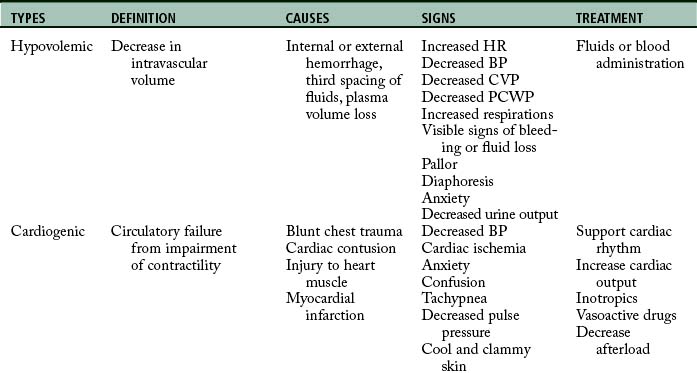

Stabilization phase

The initial assessment, resuscitation, and stabilization processes that are initiated in the emergency department and trauma center extend into the operating room (OR), the PACU, and the critical care unit. Temperature of the trauma rooms may be increased to prevent hypothermia during resuscitation. Because the most common cause of shock (Table 54-1) in the trauma patient is hypovolemia from acute blood loss, the ultimate goal in fluid resuscitation is prompt restoration of circulatory blood volume through replacement of fluids so that tissue perfusion and delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the tissues should be maintained.10–13 Rapid identification and ensuing implementation of correct aggressive treatment are vital for the trauma patient’s survival. Although hypovolemia is the most common form of shock in the trauma patient, cardiogenic shock, obstructive shock (tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade), and distributive shock (neurogenic shock, burn shock, anaphylactic shock, and septic shock) can occur. Rapid-volume infusers deliver warmed intravenous fluids at a rate of 950 mL/min with large-bore intravenous catheters.10 Many trauma centers initially infuse 2 to 3 L of lactated Ringer or normal saline solutions and then consider blood products. The fluids should be warmed to prevent or minimize hypothermia. Crystalloids, colloids, or blood products can be used for effective reversal of hypovolemia.

Crystalloids are electrolyte solutions that diffuse through the capillary endothelium and can be distributed evenly throughout the extracellular compartment. Examples of crystalloid solutions are lactated Ringer solution, Plasma-Lyte, and normal saline solution. Although controversy exists regarding crystalloid versus colloid fluid resuscitation in multiple trauma, the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma recommends that isotonic crystalloid solutions of lactated Ringer or normal saline solution be used for that purpose.11 Furthermore, crystalloids are much cheaper than colloids. Administration of crystalloids should be threefold to fourfold the blood loss.11

Colloid solutions contain protein or starch molecules or aggregates of molecules that remain uniformly distributed in fluid and fail to form a true solution.13–16 When colloid solutions are administered, the molecules remain in the intravascular space, thereby increasing the osmotic pressure gradient within the vascular compartment. Volume for volume, the half-life of colloids is much longer than that of crystalloids. Colloid solutions commonly used are plasma protein fraction, dextran, normal human serum albumin, and hetastarch.

Researchers in several new randomized control trials have used hypertonic solutions to resuscitate patients in shock.14–18 According to Beekley,18 hypertonic saline solution (3% sodium chloride) can be used in resuscitation of the child with a severe head injury because it maintains blood pressure and cerebral oxygen delivery, decreases overall fluid requirements, and results in improved overall survival rates.16 In addition, patients with low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores from head injuries have improved survival rates in the hospital.16

Although crystalloid and colloid solutions serve as primary resuscitation fluids for volume depletion, blood transfusions are necessary to restore the capacity of the blood to carry adequate amounts of oxygen. Furthermore, blood component therapy is considered after the trauma patient’s response to the initial resuscitative fluids has been evaluated.11 In an emergency, universal donor blood (type O negative for women in childbearing years) packed red blood cells can be administered for patients with exsanguinating hemorrhage. Untyped O negative whole blood can also be given to patients with an exsanguinating hemorrhage. Other blood products, such as platelets and fresh frozen plasma, may need to be given to the trauma patient because of a consumption coagulopathy. Most notable are the leukemic trauma patients with low platelet counts. With fluid resuscitation of these patients with immunosuppression, colloids are contraindicated because of the antiplatelet activity that exacerbates hemorrhaging.17 Type-specific blood often times is available within 10 minutes and is preferred over universal donor blood. Fully cross-matched blood is preferred in situations that can warrant awaiting type and cross match, which often takes up to 1 hour.10–12 Finally, the therapeutic goal of all blood component therapy is to restore the circulating blood volume and to give back other needed blood with red blood cells and clotting factors to correct coagulation deficiencies.19–22

New evidence recognizes “permissive hypotension” by keeping the patient’s systolic blood pressure at approximately 90 mm Hg correlates with better outcomes owing to conservation of important clotting factors.21 In addition, there also seems to be a protective mechanism of myocardial suppressive factors that conserve homeostasis of fluid shifts. The intent of this protective response is to prevent further hemorrhaging or bleeding out of the red blood cells and clotting factors. By sustaining the hypotension, the blood pressure supports basic perfusion until the patient is in the OR and surgically resuscitated.19,21 Damage control resuscitation and warm, fresh whole blood are now associated with better survival rates in combat-related massive hemorrhage injuries. Restoration of blood volume before homeostasis is achieved may have adverse complications of exacerbation of blood loss from increase in blood pressure.18–22

In summary, fluid resuscitation of the trauma patient is essential to ensure that adequate circulating volume and vital oxygen and nutrients are delivered to the tissues. However, new studies recommend permissive hypotension with the use of damage control resuscitation to decrease mortality and morbidity and optimize the patient’s survival.18–22 These combat-related studies are now influencing the management of civilian resuscitation of massive hemorrhage injuries in trauma centers throughout the United States.

Collaborative approach

The anesthesia provider or OR nurse communicates a comprehensive systems report to the perianesthesia nurse and verbally reviews any definitive findings of the computed tomographic scan, including whether generalized edema or lesions are found. Vital nursing information is communicated to the appropriate OR and postanesthesia nurses caring for the trauma patient. The anesthesia provider and trauma surgeon should communicate the significant findings during the intraoperative period that may be problematic during the recovery phase, what the PACU nurse should look for and report promptly to these physicians, and what the PACU nurse should do to prevent harm during the postanesthesia phase of care.23

Postanesthesia phase I

Primary assessment

Next, the postanesthesia nurse evaluates the patient’s work of breathing. While recalling the MOI, such as blunt or penetrating trauma to the chest, the nurse should be highly suspicious of pulmonary contusions, fractured ribs, or injuries from shearing forces. The nurse assesses spontaneous respirations, respiratory excursion, chest wall integrity, symmetry, depth, respiratory rate, use of accessory muscles, and the work of breathing. With palpation, the nurse should evaluate for the presence of subcutaneous emphysema, hyperresonance or dullness over the lung fields, and tracheal deviation. With auscultation, the nurse assesses the lungs for bilateral breath sounds and evaluates for adventitious breath sounds. In addition, pulse oximetry and end-tidal CO2 monitoring augment the complete respiratory assessment of the trauma patient.

The final component of the primary survey is the disability or neurologic examination. The patient’s mental status should be assessed with the AVPU (Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive) scale or the GCS. The AVPU is described as follows: A for awake and responding to nurse’s questions; V for verbal response to nurse’s questions, P for responding to pain; and U for unresponsive.10,11 The GCS is used in many PACUs for evaluating neurologic status and predicting outcomes of severe trauma. This neurologic scoring system allows for constant evaluation from field to emergency room to PACU. One must remember that anesthesia blunts the neurologic response; therefore the response is not as useful in the immediate postanesthesia period. Next, bilateral pupil response is evaluated for equality, roundness, and reactivity: brisk, slow, sluggish, or no response to light and accommodation. Before the primary assessment is complete, the PACU nurse quickly reassesses the ABCDs for stability and then is ready to receive a report from the anesthesiologist.

Anesthesia report

Another important aspect of the anesthesia report is estimated blood loss and fluid replacement, which are carefully monitored through the hemodynamic status of the trauma patient. With the use of arterial lines and pulmonary artery catheters, the anesthesiologist can closely monitor the patient’s hemodynamic status. In severe chest injuries, closed chest drainage units and auto transfusions or Cell Saver blood recovery systems can be used to conserve the vital life-sustaining resource blood. Because the goal of treatment is to keep the patient in a hyperdynamic state, the intraoperative trending should reveal that the patient is volume supported, because the body responds hypermetabolically to trauma and achieving that state ensures the delivery of oxygen and other nutrients to essential tissues in the body. End-organ perfusion is monitored and measured with the urinary output and hemodynamic monitoring. Urinary catheters are essential in management of fluids in the trauma patient and assessment of kidney function. Hemodynamic monitoring reflects the body’s hydration status and reveals the work of the heart. A detailed operative report reveals the surgical insult to the patient. It also presents a comprehensive review of all anesthetic agents that reflects a rapid sequence of induction, balanced analgesia, and heavy use of opioids, including the time these agents were given and the amount and type of muscle relaxants and reversal agents used. The anesthesia report should reveal any untoward events that occurred during surgery, such as hypothermic or hypotensive events and significant dysrhythmias, including ischemic changes.

Secondary assessment

The next areas to be inspected are the abdomen, pelvis, and genitalia. All abrasions, contusions, edema, and ecchymoses are noted. The abdomen is auscultated for bowel sounds before palpation for tenderness and rigidity. The nasogastric tube, jejunostomy, or tube drainage is examined for color, consistency, and amount of fluid. In suspected internal abdominal or retroperitoneal hemorrhage, abdominal compartment measurements should be assessed. Some common causes of abdominal compartment syndrome are pelvic fractures, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma, bowel edema from injury, septic shock, and perihepatic or retroperitoneal packing for diffuse nonsurgical bleeding. If intraabdominal hypertension or abdominal compartment syndrome are suspected or considered, the standard of care is measurement of bladder pressures.24 A catheter or similar device is connected to a pressure transducer that is connected to the urinary catheter. The urinary catheter is clamped near the connection, 50 mL of saline solution is instilled to the bladder, the transducer is leveled at the symphysis pubis, and the pressure is measured at end expiration. If the pressure is elevated, a decompression laparotomy should be performed to release the pressure that develops from bowel edema.24 The abdomen is then left open and covered with a sterile wound vacuum until the swelling has resolved and the abdomen can be closed.

The pelvis is palpated for stability and tenderness, especially over the crests and the pubis. Priapism, which is persistent abnormal erection, may be noted.10,11 In addition, preexisting genital herpes may also be present. The urinary catheter is inspected for color and amount of drainage. Urinary output should be at least 0.5 to 1.0 mL/kg/h in adults and 1 to 2 mL/kg/h in children.8 Hematuria can indicate kidney or bladder trauma. Furthermore, urinary output must be vigilantly monitored to ensure a minimum of 30 mL/h in adults so that the patient does not develop acute renal failure from rhabdomyolysis, which can occur after traumatic injuries. The vagina and rectum are checked carefully for neurologic function and bloody drainage.

Pain

Assessment and management of pain are important parts of the scope of care provided to the trauma patient in the PACU. The trauma patient may have musculoskeletal injuries or ruptured organs that cause severe pain, which may include more than the surgical site. Identification of alcohol or opioid withdrawal requires a specialized management approach and may be difficult to assess in the patient with multiple traumas during the postanesthesia period. Substance abuse pain assessment scales, such as the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment Scale and Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment Scale, are more appropriate.25 The perianesthesia nurse needs to recognize that because pain is subjective, verbal, nonverbal, and hemodynamic, changes that indicate the patient may be exhibiting signs of pain should be noted. Pain can manifest itself with increased heart rate, increased blood pressure, pallor, tachypnea, guarding or splinting, and nausea and vomiting. Pain scales should be used to augment the nursing assessment of pain.

Optimal management of acute pain may use the following techniques: (1) patient-controlled analgesia with intravenous or epidural infusions; (2) intravenous intermittent doses for pain or sedation; and (3) major plexus blocks. Guidance for medications should be based on choosing drugs that minimize cardiovascular depression and intracranial hypertension. A higher incidence rate of substance abuse, both alcohol and recreational or addictive mind-altering drugs, in the trauma patient population may require higher doses of opioids or analgesics.25,26 Other complementary techniques, such as music therapy and guided imagery, may be initiated and used as adjuncts when the trauma patient returns for subsequent surgical procedures or wound debridement. Finally, continual pain assessment is vital to the patient’s optimal care.

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Trauma patients can emerge from anesthesia in a confused or combative state because of pain, disorientation, or PTSD. Emergence delirium or emergence excitement is a recognized complication of patients recovering from anesthesia. Trauma patients are at increased risk for emergence delirium because of PTSD that occurs after the experience or witnessing of life-threatening events, such as military combat, a terrorist incident, a natural disaster, or sexual assault.27 The PACU nurse should be prepared to critically assess the patient on emergence from anesthesia for restlessness, agitation, “thousand-mile stare,” or sudden outbursts when the patient experiences flashbacks from the traumatic event.27 The nurse must provide a calm, soft, but directive communication, always remembering to orient the recovering patient from anesthesia. Family or friends may be appropriate visitors in PACU Phase I to help orient the patient to an unfamiliar hospital environment. In severe cases of PTSD, the PACU nurse should consider collaborating with an anesthesia provider to resedate the emerging patient.27 As the patient emerges from anesthesia, the perianesthesia nurse orients the patient to place and time. Because the patient might not remember or recall the event that caused the accident, the nurse orients the patient to the hospital. Fear of death, mutilation, or change in body image can increase the patient’s anxiety. The trauma patient may regain consciousness only to find that the extremities are immobilized or amputated. Because a high incidence rate of injuries is related to alcohol or substance abuse, the patient may have no memory of events before, during, or after the injury. The patient may have alterations in visual and auditory functions. If the patient was alert at the scene and remembers that loved ones were severely injured or killed, the patient may become upset or hysterical, often reliving the tragic event. Consequently, the patient not only experiences loss of body integrity and control, but also the loss of loved ones.

The perianesthesia nurse needs to be supportive yet focused on maintaining the patient’s integrity and coping skills. The nurse needs to speak to the patient calmly, slowly, and clearly, with simple language that is easily understood. Often the same information has to be repeated as the patient emerges from anesthesia. The clinician should be honest with the patient. Psychologic aspects of trauma care include the following three concepts, according to the Emergency Nurses Association: (1) need for information, (2) need for compassionate care, and (3) need for hope.10

Shock as A complication in the patient with multiple traumas

The most common complication associated with traumatic injuries is shock. Although different types of shock exist, all types exhibit a profound problem with inadequate delivery or utilization of oxygen and nutrients to the cells. Consequently, this anaerobic state results in inadequate tissue perfusion.28–35 A measure of the body’s overall metabolism is expressed as oxygen consumption (VO2) and oxygen delivery to the cells (DaO2).28 When VO2 is inadequate, cellular hypoxia evolves. The magnitude of oxygen debt correlates with the lactic acid levels, and this measurement quantifies the severity and prognosis in different shock states.28 Consequently, this complex syndrome of disequilibrium between oxygen supply and demand causes a functional impairment (oxygen debt) in cells, tissues, organs, and eventually body systems.28 Vital tissues such as the brain, heart, and lungs require large amounts of oxygen to support their specialized functions. Other important tissues, such as the liver, kidney, and gut, need essential amounts of oxygen to support their specialized functions. Furthermore, these functions can be maintained only with energy derived from aerobic metabolism, and they cease when oxygen is in short supply.

Clinical manifestations of shock include signs and symptoms of decreased end-organ perfusion: cool, clammy skin; cyanosis; restlessness; altered level of consciousness; altered skin temperature; tachycardia; dysrhythmias; tachypnea; pulmonary edema; decreased urinary output; increased platelet, leukocyte, and erythrocyte counts; sludging of blood; and metabolic acidosis.34

Types of shock

The four major types of shock are hypovolemic, cardiogenic, obstructive, and distributed (see Table 54-1). The first and most common type of shock, hypovolemic, results from an acute hemorrhagic loss in circulating blood volume that decreases vascular filling pressure.32,33 Cardiogenic shock results from an inadequate contractility of the cardiac muscle; it is rare in the trauma patient, but can be caused by blunt cardiac injury or myocardial infarction (MI). In obstructive shock, obstruction or compression of the great vessels or the heart itself is the cause. Both tension pneumothorax and cardiac tamponade can cause obstructive shock.10,11 Distributive shock causes an abnormality in the vascular system and activation of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and produces a maldistribution of blood volume.29,30 Distributive shock includes neurogenic, anaphylactic, and septic types. The most common type among trauma patients is neurogenic shock from spinal cord injuries.

Hypovolemic shock

Hypovolemic shock is the decrease in intravascular volume that results in the fluid volume ineffectively filling the intravascular compartment.29 Consequently, hypovolemic shock can evolve from many causes, such as internal and external hemorrhage, plasma volume loss in burns, third spacing of fluids, and decreased venous return.32,33

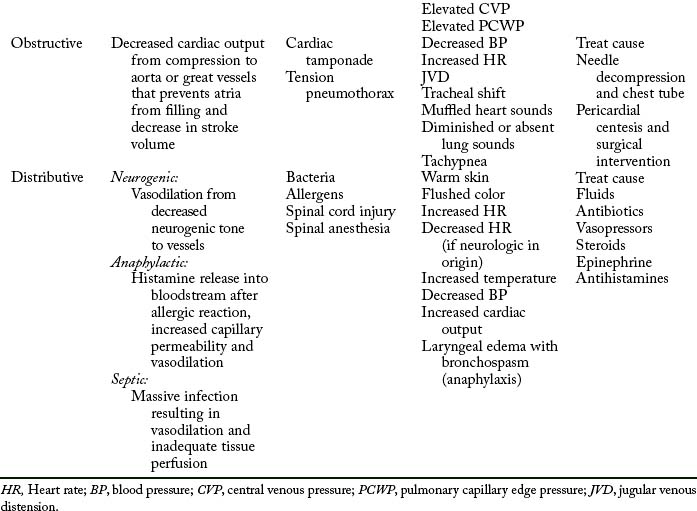

Classifications of hemorrhage

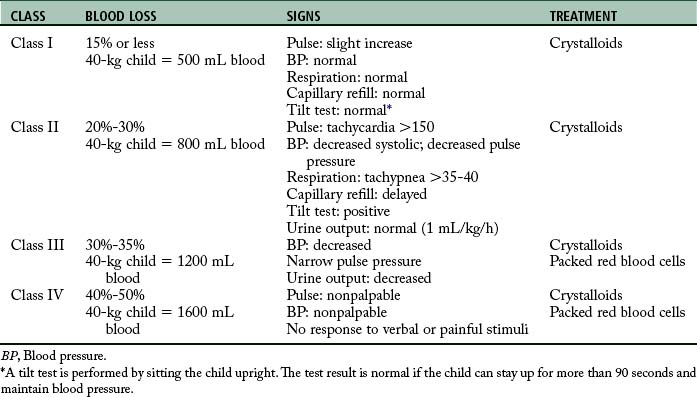

As hemorrhage progresses, the cardiovascular system produces characteristic clinical manifestations that are classified according to approximate blood loss (Table 54-2).11 The following hemorrhagic classifications are described in the conceptual framework of the Committee on Trauma of the American College of Surgeons Advanced Trauma Life Support Course.11

Class I hemorrhage, or the early phase, is the loss of as much as 750 mL of blood, or 1% to 15% of the body’s total blood volume. Minimal physiologic changes occur in heart rate, blood pressure, capillary refill, respiratory rate, and urinary output. However, the patient may have mild anxiety in response to the sympathetic nervous system.

Class IV hemorrhage is the loss of more than 2000 mL of blood, or approximately 40% of the body’s blood volume. This significant blood loss profoundly affects the trauma patient. The patient’s level of consciousness may be lethargic, stuporous, or unresponsive. The heart rate may be 140 beats/min or greater, and the peripheral pulses may be weak and difficult to palpate. The capillary refill time may be more than 10 seconds. The patient may have severe hypotension, and blood pressure may be difficult to obtain. The skin may be cold, clammy, diaphoretic, or cyanotic. The respiratory rate is shallow, irregular, and greater than 35 breaths/min. Finally, no renal end-organ perfusion occurs, which results in anuria.11

According to the American College of Surgeons Advanced Trauma Life Support Course11, the treatment of patients with blood loss hemorrhage is infusion of crystalloids and possibly blood. A rough guideline for the total volume of replacement fluid is 3 mL of crystalloid for each 1 mL of blood loss.10,11 This guideline is referred to as the 3:1 rule.11 When the blood loss results in a class III hemorrhage, administration of blood should be considered; the patient with a class IV hemorrhage needs blood administration and without aggressive measures dies within minutes. The goal is assessment of the patient’s response to fluid resuscitation and evidence of adequate end-organ perfusion and oxygenation (e.g., urinary output, level of consciousness, tissue perfusion). The same signs and symptoms that alert the presence of shock must be reassessed to determine the patient’s response.11 The first hour after injury is termed the golden hour, in which successful treatment of shock is associated with lower mortality.34,35

Cardiogenic shock

Cardiogenic shock induced by inadequate cardiac output usually occurs in the trauma patient as a result of blunt injury to the heart muscle (e.g., contusions and ruptured heart or injury to heart valves or septa) or occasionally MI.10,11,30 MIs, however, may either precipitate or precede the traumatic event. Consequently, the patient with a history of heart disease or age-related cardiac reserve limitations or who needs myocardial depressants, such as anesthesia, has a high propensity for cardiogenic shock.34 Finally, this trauma patient population is also at greater risk for developing cardiac failure because of the rapid fluid resuscitation.

Another method to classify causes of cardiogenic shock is identification of the shock as either coronary or noncoronary. Rice32 described coronary cardiogenic shock as an obstructive coronary artery disease process that interrupts blood flow and oxygen delivery to heart muscle cells, resulting in ischemia and death. The infarcted area of heart muscle is necrotic and dead and thus provides no function. Because the area of infarction and the surrounding area of ischemic heart muscle do not contract normally, the heart is unable to maintain forward blood flow or cardiac output.

Patients with acute MIs are at greatest risk of developing cardiogenic shock, especially when a significant portion (myocardial injury, >40%) of the left ventricle is involved. This loss of contractility reveals a low cardiac output, elevated left-ventricular filling pressure, peripheral vasoconstriction, and arterial hypotension. Another problem involves the volume of blood that accumulates in the left ventricle after systolic ejection and increases the left-ventricular filling pressure. This back-pressure mechanism causes the following sequence of events: (1) an increased left-atrial pressure; (2) an increased pulmonary venous pressure; and (3) an increased pulmonary capillary pressure that results in pulmonary interstitial edema and intraalveolar edema.34 A small percentage of MIs, however, involve the damaged right ventricle, which does not propel sufficient blood forward through the lungs into the left heart.34 Cardiac output decreases, and systemic circulation is insufficient to maintain the body’s needs.

As discussed previously, noncoronary cardiogenic shock can develop in the absence of coronary artery disease and heart muscle damage, such as with cardiomyopathies, valvular heart abnormalities, cardiac tamponade, and dysrhythmias.34

Cardiogenic shock is defined as shock from acute myocardial dysfunction, including the following clinical and diagnostic criteria: systolic blood pressure less than 80 mm Hg, or less than 30 mm Hg of baseline in the patient with hypertension; cardiac index less than 2.1 L/min/m2; urinary output less than 20 mL/h; diminished cerebral perfusion evidenced by confusion or obtundation; and cold, clammy, cyanotic skin characteristic of a low cardiac output state. However, classic signs and symptoms of cardiogenic shock, such as pulmonary congestion, edema, neck vein distention, and hepatic congestion, may not be seen in the trauma patient with coexisting acute hypovolemia.

Treatment

When pharmacologic support fails to improve the oxygen supply-and-demand balance, alternative methods such as the intraaortic balloon pump and the right-ventricular and left-ventricular assist devices help to increase myocardial oxygen supply, decrease myocardial VO2, relieve pulmonary congestion, and improve organ perfusion.34,35

Distributive shock

Neurogenic shock

Neurogenic shock reflects the domination of the parasympathetic nervous system and results in venous pooling and bradycardia. Neurogenic shock can occur from acute spinal cord injury or in patients who are paraplegic or quadriplegic and have a full bladder. Decreasing bladder pressure with catheterization helps to resolve symptoms in the patient with nonacute spinal cord injury. Likewise, neurogenic shock is described as a tremendous increase in the vascular capacity such that even the normal amount of blood becomes incapable of adequately filling the circulatory system.35 When the body has an increase in vascular capacity, the mean systemic pressure decreases, which causes a decreased venous return to the heart. Because the sympathetic nervous system causes vasoconstriction to maintain vascular tone, the loss of sympathetic enervation results in domination of the parasympathetic nerves, causing vascular dilation (or venous pooling). This massive vasodilation of veins occurs as a result of the loss of sympathetic vasomotor tone. Neurogenic shock, however, often is transitory and does not commonly occur.

Because massive unopposed vasodilation induces arterioles to dilate, decreasing peripheral vascular resistance, venules and veins also dilate and thus cause blood to pool in the venous vasculature and decrease venous return to the right heart.30,31 Consequently, the following series of events occurs: (1) decreased ventricular filling pressure, (2) decreased stroke volume, (3) decreased cardiac output, (4) decreased blood pressure, (5) decreased peripheral vascular resistance, and (6) decreased tissue perfusion.

Treatment

The treatment of neurogenic shock may require extensive volume expansion and the use of vasopressors, such as ephedrine. In the case of spinal anesthesia, the perianesthesia nurse should place the patient in a supine position and, if possible, decrease the head of the bed elevation and elevate the legs. Finally, the goal of treatment in neurogenic shock is to balance volume expansion with the titration of vasopressor administration.32,33,34,35

Anaphylactic shock

Anaphylactic shock results from a severe antigen-antibody reaction. Although this type of shock is not commonly seen in trauma patients, the condition can occur as an iatrogenic complication during resuscitation.29–32 Other causes of anaphylactic shock are reactions to antibiotics, contrast media, and blood transfusions.

The pathophysiologic response of anaphylaxis relates to the systemic inflammatory response syndrome process and the activation of the complement and arachidonic cascades. The sequence of events involved in the development of anaphylactic shock are divided into three phases32,33,34,35:

1. The sensitization phase, in which immunoglobulin E antibody is produced in response to an antigen and binds to mast cells and basophils

2. The activation phase, in which reexposure to the specific antigen triggers mast cells to release their vasoactive contents

3. The effector phase, in which the complex response of anaphylaxis occurs as a result of the histamine and vasoactive mediators released by the mast cells and basophils

These vasoactive mediators act on blood vessels and cause massive vasodilation and increased capillary permeability, which allows fluid to leak from the intravascular space to the interstitial space.30

Treatment

Aminophylline can be administered to reduce bronchial constriction and wheezing and to minimize respiratory distress.35 Diphenhydramine, an antihistamine, is another drug of choice. Corticosteroids can be used to decrease the inflammatory response. Finally, gastric acid blockers such as the histamine 2 (H2) blockers (famotidine, ranitidine) are given.

Septic shock

Septic shock is the most common type of distributive shock and results from an acute systemic response (systemic inflammatory response syndrome) to invading bloodborne microorganisms. The sepsis can be caused by gram-positive bacteria; however, the most common cause is gram-negative bacteria. Other pathogens that can cause septic shock are viruses, fungi, parasites, or rickettsiae. The trauma patient is predisposed to the following determinants that affect the outcome of septic shock: infection as a result of contaminated wounds, poor nutritional status, preexisting disease state, and altered integrity of the body’s defense mechanisms.32,33,35 Furthermore, sepsis-associated tissue damage is a major complication and remains the principal cause of death in trauma patients who survive the first 3 days after injury.34

Septic shock is a clinical syndrome that, on a continuum, begins with sepsis and ends with multisystem organ dysfunction or failure. Septic shock is primarily a complex cellular disease that results in a loss of autoregulation and in tissue dysfunction that occurs early and persists despite increased cardiac output. Interactions between bacterial toxins and the body’s cellular, humoral, and immunologic systems are considered to activate the kinins and complement, arachidonic, and coagulation cascades, which generate other endogenous mediators that only intensify regional malperfusion.12,28–35

The profound hemodynamic instability of septic shock is revealed in the body’s biphasic response. The first phase, or the hyperdynamic response, is characterized by a high cardiac output and a low systemic vascular resistance; the second phase, the hypodynamic response, reflects the classic shock picture with a low cardiac output and an extremely high systemic vascular resistance.28–31 These phases are also referred to as early shock, or a warm hyperdynamic phase, and late shock, or a cold hypodynamic phase. During early shock, the patient’s skin is pink, warm, and dry because of the increased cardiac output and peripheral vasodilation. With progressing shock, fluid leaks from the vascular compartment, and the patient develops relative hypovolemia, with decreasing cardiac output and increasing peripheral vasoconstriction.33,34 The clinical manifestations of late shock are cold and clammy skin, decreased cardiac output, severe hypotension, and extreme vasoconstriction.35

In septic shock, the degree of myocardial depression is directly related to the severity of sepsis. Decreased force of contractions may be the result of the release of vasoactive chemical mediators, such as myocardial depressant factor, endotoxins, tumor necrosis factor, complement, leukotrienes, and endorphins.32–35 Furthermore, decreased ventricular preload from increased capillary permeability augments the myocardial depression.

Rice32,33 describes alterations in peripheral circulation as massive vasodilation that occur as a result of mediator activation of the bradykinins, histamines, endorphins, complement split products, platelet-activating factor, and prostaglandins.32–35 Another aspect of altered circulation is observed in the maldistribution of blood volume that occurs when some tissues receive more blood flow than is needed and other tissues are deprived of needed oxygen and nutrients. Finally, increased capillary permeability causes reduced circulating blood volume, increased blood viscosity, hypoalbuminemia, and interstitial edema.35

One of the first target organs to be affected in septic shock is the lung.28,33,34 Endotoxin stimulates the production of complement split products, producing bronchoconstriction, and the release of other vasoactive mediators that cause neutrophil and platelet aggregation to the lungs increases capillary permeability. Consequently, fluid collects in the interstitium and increases diffusion distance, decreases compliance, and thereby causes hypoxemia. Pulmonary vasoconstriction may be caused by thromboxane A2, which augments capillary permeability and leads to acute respiratory distress syndrome or acute lung injury.30,33

Septic shock also causes a profound alteration in metabolism. This metabolic dysfunction is attributed to the following: (1) increasing oxygen debt and rising blood lactate levels, (2) sustained proteolysis, (3) altered gluconeogenesis with concurrent insulin resistance, and (4) liberation of free fatty acids.34

Treatment

The treatment of septic shock consists of identifying and eliminating the focus of infection. With culturing of the blood, urine, sputum, wound drainage, and invasive lines, the organism can be identified, and the proper definitive antimicrobial therapy can be initiated. Hemodynamic monitoring ensures an accurate means to assess the patient’s circulatory status and the patient’s response to therapeutic interventions. Initially, the perianesthesia nurse may elect to use supplemental oxygen and encourage the patient to breathe deeply. However, as the shock state progresses, the patient’s respiratory status becomes compromised. Aggressive ventilator support must be established to maintain adequate oxygenation and tissue perfusion. Proper selection of parenteral fluid administration is important in correcting the cause of shock and supporting tissue perfusion.32–33,35–36

Pharmacologic support, including the use of positive inotropes (primarily dopamine, dobutamine, norepinephrine) and vasodilators (primarily nitroprusside and nitroglycerin), may be indicated to augment contractility, preload, and afterload. New evidence supports glycemic control to assist in control of the stress response.36 Finally, promising research suggests that the use of arginine vasopressin in refractory septic shock, despite adequate fluid volume resuscitation and high-dose vasopressor therapy, helps to restore mean arterial pressure and is catecholamine sparing in septic shock.36

Obstructive shock

Obstructive shock is caused by an obstructive source such as acute pulmonary embolism, dissecting aortic aneurysm, vena cava obstruction, cardiac tamponade, or tension pneumothorax. The result of all these pathologic mechanisms is decreased cardiac output from compression to the atria, which prevents the atrium from filling and thus leads to decreased stroke volume. Cardiac tamponade can compress the atria during diastole so that the atria cannot fill completely, resulting in decrease in stroke volume results.10 Displacement of the inferior vena cava can obstruct return of venous blood to the heart, building up pressure as in a tension pneumothorax. Clinical manifestations are in alignment with causative mechanisms.

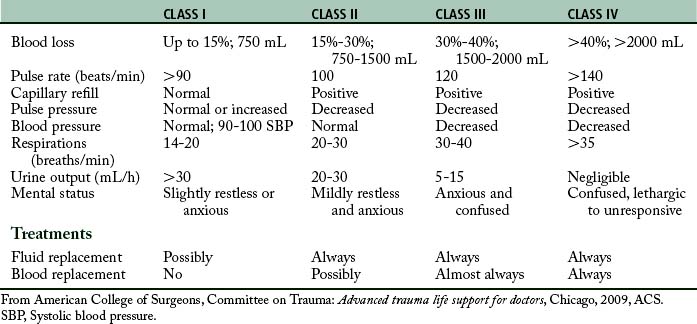

Pediatric trauma

Pediatric trauma continues to be the leading cause of death in children older than 1 year.37,38 These injuries significantly affect not only the children, but also the parents and the entire family unit. Furthermore, their health care problems lead to complex psychological trauma, increased financial burden, and the long-term medical costs for rehabilitation. Foremost, the postanesthesia nurse needs to understand the epidemiology of pediatric trauma, the risk factors related to the developmental ages (Table 54-3), and the unique pediatric anatomic and physiologic differences that directly affect the optimal management of the patient. Likewise, the PACU nurse should recognize the symptoms of families in crisis as well as signs of psychological posttraumatic stress in order to effectively intervene and promote coping techniques with the child and parents. Finally, the postanesthesia nurse should facilitate family visitation during invasive or resuscitative events in the PACU as an advocate for the preservation of the family unit.

Epidemiology

Millions of children are seriously injured each year in the United States. Unintentional injuries are the leading cause of pediatric deaths of more than 21,000 children, adolescents, and young adults.38 Interestingly, unintentional deaths peak during the toddler–preschool period and then again during adolescence and young adulthood. Although the most common injuries are open wounds, superficial injuries, contusions, dislocations, sprains, and strains, the more significant trauma injuries are blunt trauma, intracranial injuries, and burns.10,11,39 Key predictive risk factors related to age group and types of injuries are the following: infants sustain suffocation, motor vehicle crashes (MVCs), burns and falls; toddlers and preschool-age children who sustain MVCs, drowning, fires, burns, suffocations, and falls; school-age children start to engage in more risk-taking behaviors that are linked to pedestrian injuries, bicycle injuries, drowning, and firearms; and finally MVCs lead the category in adolescent trauma injuries.40–42 Overall age and gender are important characteristics and reflect that male children have higher injury and mortality rates than females.40 Likewise, children with attention deficit disorders have a 1.5-fold greater risk of injury.38 Effective injury prevention education and research continue to promote keeping children safe and decreasing the risk of traumatic injuries.41

Pediatric pathophysiology

Airway

The child’s mouth is relatively small compared with the child’s large tongue, which can easily obstruct the airway. Furthermore, neonates and infants are obligate nose breathers and may become distressed if their nose becomes obstructed by mucus, blood, or foreign bodies. Likewise, the pediatric epiglottis is omega-shaped and floppy, the larynx is higher and more anterior, the tracheal length is only 4 to 5 cm in infants, and the cricoid ring is the narrowest part of the airway, making it more difficult to intubate the infant and young child.,43 It is vital to ensure that the child’s airway is patent.

Breathing

Another critical assessment is breathing to ensure adequacy of the respirations. The postanesthesia nurse carefully evaluates the work of breathing by assessing the rise and fall of the chest, respiratory effort (use of accessory muscles), efficacy, quality of the bilateral breath sounds, and oxygenation.44 When the child is intubated, end-tidal CO2 may be monitored continuously. The PACU nurse needs to be vigilant in continually assessing the rate and work of breathing. Signs and symptoms of impending respiratory distress or failure are the following: respiratory rate greater than 60 breaths/min, nasal flaring, noisy, stridor, coarse rales, cyanosis, altered mental status, and irregular breathing patterns. It is important that the nurse be ready to intervene and be able to provide ventilatory support and oxygenation via the bag-mask device.

Circulation

The most common cause of shock in the pediatric trauma patient is hypovolemia through blood loss. One of the important circulation assessments for adequate end-organ perfusion is through palpating the central versus distal pulses and counting the pulse for 1 minute because of irregularities in an anxious or injured child. Pediatric patients are volume sensitive and in low-perfusion states will shunt their circulating blood to their vital organs. In hypotensive or low-flow states, the child’s extremities will be cool to the touch, and distal pulses will be weak to nonexistent. One may find tachycardia in children with conditions such as a fever, anxiety, or early shock. However, bradycardia is an ominous sign that may reflect hypoxia, hypoglycemia, hypothermia, spinal cord injury, or increased intracranial pressure. In infants, it is essential to keep in mind that they have not yet developed the ability to compensate for hypovolemia by increasing heart rate; therefore bradycardia is especially concerning. Children maintain such strong circulatory compensatory mechanisms that even with a loss of 25% to 30% circulating blood volume loss, their bodies can maintain blood pressures through peripheral and superficial vasoconstriction (Table 54-4). Therefore hypotension is a late sign of hypovolemia. Accurate blood pressures should be assessed with the correctly sized cuff. It is important to assess for sources of external bleeding and, if found, apply direct pressure. Foremost to ensuring effective volume resuscitation is the need to assess the intravenous site for patency and that the fluid infuses properly.

Neurologic

Head injuries are the leading cause of death in children because of their large head size, proportionally larger cranial blood volume, malleable skull, and incomplete myelinization of brain tissues that renders the brain vulnerable to shearing forces. A careful, thorough neurologic examination begins with assessing the level of consciousness, motor response, pupil size, and reactivity. The AVPU method of assessment determines the child’s response to external stimulation.10,11 The child whose level of consciousness changes, such as failure to recognize parents and failure to response to painful procedures (e.g., drawing blood, insertion of intravenous catheter), or becomes sleepy or lethargic should be reassessed frequently and monitored closely. Vomiting and irritability are early signs of increased intracranial pressure. The effects of elevated increased intracranial pressure may be revealed in Cushing triad: hypertension, bradycardia, and abnormal breathing patterns. Consequently, this severe compromise of blood flow to the brainstem indicates impending herniation that requires immediate emergency interventions. The goal of caring for the child with head trauma is to prevent or limit the secondary reperfusion injury to the brain.44

Urinary output

Urinary output is a measure of end organ perfusion in the kidneys. Urine output can vary with age. Output for the following ages groups should be expected: 2 mL/kg/h for infants (1-12 months), 1.5 mL/kg/h for younger children, and 0.5 mL/h for older children.10,11

Pain management

The management of pain is an important aspect in the care of pediatric patients. The management of acute pain in pediatric patients includes both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities. Common pharmacologic interventions most often used in the PACU include nonopioid (e.g., acetaminophen, salicylates, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs) and opioid medications (e.g., fentanyl, morphine, hydromorphone), dissociative medications (e.g., ketamine), anxiolytics medications (e.g., midazolam), and local nerve blocks.45 Nonpharmacologic techniques that are often used include guided imagery, music therapy, videos, toys, massage, cold, and warmth therapy.45 Optimally, the combination of nonpharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions provide the best methods to decrease the traumatic pain experience in children and promote the healing process.25

Obstetric trauma

Acute traumatic injury during pregnancy is the leading cause of maternal death in the United States.46–51. Major causes of injury-related maternal deaths are from blunt trauma (e.g., MVCs, abdominal), penetrating trauma (e.g., gunshot wounds, stab wounds), burns, falls, and assaults.46–51 Even more alarming is the significant rise in the incidence of domestic violence during pregnancy.52,53 Tragically, these lethal injuries affect not only the pregnant woman, but also the unborn fetus she is carrying. Likewise, the risk of trauma to the mother and fetus increases as the pregnancy progresses, mainly because of the increasing size of the developing fetus and uterus.51 Consequently the rapid, effective resuscitation of the mother is of paramount importance, because fetal survival is directly related to the maternal well-being.49 Because there is a high maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality associated with these injuries, a multidisciplinary team approach to the acute management of their injuries is essential for optimal outcomes for both the mother and her baby.46

Epidemiology

According to Muench and Canterino,54 although trauma complicates 6% to 7% of all pregnancies, it is the leading cause of nonobstetric maternal morbidity and mortality. As the size of the developing uterus and fetus expand, the risk to the mother and unborn baby also increases. Furthermore, there is direct correlation between the multiple anatomic and physiologic changes that occur during pregnancy and the movement of abdominal organs from the lower abdominal or pelvic regions to the upper abdominal and thoracic cavities,55 thus exposing the pregnant patient to increased risk of traumatic injury.

Placental abruption

The mechanism for placental abruption is related to the difference between the tissue properties of the elastic myometrium and the inelastic placenta.55 Placental abruption is caused by shearing forces at the placental-uterine interface. Because amniotic fluid is not compressible, impact against the uterine wall results in amniotic fluid displacement and uterine distention. 55 Abruption can occur immediately after abdominal trauma impact or be delayed for several hours after the trauma episode.

Uterine rupture

Blunt trauma to the abdomen of the pregnant patient can be so severe that it causes the uterus to rupture. Adding to the severity of injury is the increased vascularity that could result in severe hemorrhage. The greater the hemorrhage the more rapid the need for replacement of blood and clotting factors required to prevent disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.46

Obstetric pathophysiology

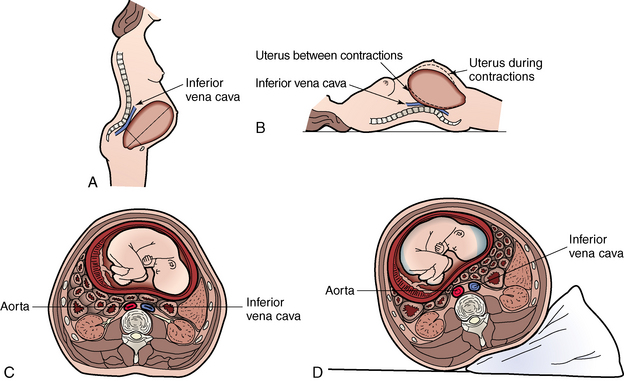

During pregnancy, anatomic and physiologic changes occur in almost all maternal organs and complicate the anesthetic care and postanesthesia management of the trauma patient.55–60 Anatomically, as pregnancy advances, there is compression and displacement of the pelvic, abdominal and thoracic organs.56 The diaphragm rises, causing the heart to rotate on its axis while moving upward to the left; the small bowel is also displaced upward, increasing its vulnerability to penetrating traumatic injuries.56,57 Another important phenomenon that occurs after 20 weeks’ gestation is the enlarged uterus compressing the aorta and vena cava when the pregnant woman is lying supine, causing decreased venous return and uterine perfusion. Furthermore, as the uterus increases in size, it displaces the bladder upward and out of the pelvis, making it more vulnerable to rupture.58,60 The physiologic changes involve the hematologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and renal systems.

Airway

There are several airways considerations when caring for the pregnant patient. The airway may become more difficult to visualize during intubation because of: weight gain, especially in the breast tissue; the position of the larynx being pushed upward more anteriorly; the mucosa of the larynx and pharynx becoming edematous and friable from the increase in extracellular fluid and vascular engorgement; and severe bleeding occurring from direct laryngoscopy, endotracheal intubation, or advancing a nasogastric tube.59

Breathing (pulmonary)

The changes that occur in the pulmonary system reflect the following: (1) increased tidal volume (45%) and minute ventilation (40%); (2) decreased functional residual capacity (25%); (3) increased oxygen consumption (60%); differences in ventilation and lung volumes result in respiratory alkalosis with a metabolic acidosis secondary to compensation.59 Consequently, the pregnant trauma patient rapidly develops a metabolic acidosis because of hypoperfusion and hypoxia because of the decreased ability to buffer, as well as developingasdecreased functional residual capacity and increased oxygen consumption. The pregnant trauma patient is extremely prone to hypoxia during periods of apnea and needs to consistently be preoxygenated before intubation.59

Circulation (cardiovascular)

Cardiac output increases 30% to 50%, and heart rate increases 15 to 20 beats/min, while the systemic vascular resistance decreases approximately 35%.56 As the pregnancy progresses, uterine compression of the vena cava may decrease venous return in the supine patients causing a 30% decrease in cardiac output;56 this is frequently referred to as aorta compression or supine hypotension syndrome. The nurse should roll the pregnant patient to the left lateral position to improve the perfusion (Fig. 54-1). Depending on the patient’s potential spinal injuries, an alternative method of displacing the uterus includes placing the patient on a backboard at a 15-degree angle until the spinal injury has been ruled out.

Gastrointestinal

The following gastrointestinal changes have an important role in the pregnant trauma patient: progesterone slows gastric emptying and decreases the tone in the esophageal sphincter, and the abdominal contents and diaphragm are pushed upward by the gravid uterus, causing the increased risk of aspiration.56 Finally, the peritoneum and abdominal muscles are stretched over time, causing a decreased sensation to abdominal pain.

Genitourologic

Common urologic changes seen in pregnancy include: upward displacement of the urinary bladder, placing this organ at an increased risk for rupture; dilation of the ureters; urine blood flow increase from 60 to 600 mL/min at term; and widening of the symphysis pubis and the sacroiliac joints by the seventh month of pregnancy.55 Blunt trauma to the abdomen leads to the potential for massive blood loss as well as placental abruption.59,60

Hematologic

The increase in the maternal blood volume increases by approximately 1500 mL or 40% above prepregnancy baseline, or approximately 2:1 plasma to red blood cells; this causes the dilutional effect or results in a physiologic anemia.59 White blood cells may increase to 20,000 to 30,000 cells/mm3 during the last trimester.60 The blood has a greater tendency to clot because of the increase in different clotting factors causing an altered clotting cascade. Likewise, there is an increase in fibrinolytic activity with factors VII, VIII, and IX.59 Consequently, the pregnant trauma patient is susceptible to pulmonary embolus.

Postanesthesia care unit management

The PACU nurse needs to perform systematic primary and secondary postanesthesia assessments on the pregnant trauma patient. The nurse focuses on assessing the mother’s airway, breathing, circulation, and neurologic systems first to determine the stability of oxygenation, ventilation, and perfusion of the tissues. High-flow oxygen is a requirement to properly oxygenate the mother and the fetus. According to Tweddale,51 respiratory changes during pregnancy are comparable to someone exerting themselves with moderate exercise. As a result, it is prudent to monitor the pulse oximetry closely and to consider providing the trauma obstetric patient with a 100% nonrebreather mask during recovery in the PACU. Remember that the pregnant patient has extra intravascular reserve accumulating and that cardiac output and preload remain constant even in the presence of hemorrhage. It is especially important to remember that fetal survival is dependent on the uterus being adequately perfused and the fetus being well oxygenated.49 As the uterus becomes more gravid and increases, the inferior vena cava or aorta can become compressed, leading to a decrease in cardiac output, increase in venous perfusion, and decrease in perfusion pressure in the uterus.51 The PACU nurse should place the pregnant patient on the mother’s left side under the right hip. It is important to note that the supine position may compromise the patient’s cardiac output by 30%. The neurologic evaluation is also an important component in the primary survey. During the secondary survey, the uterus and fetus are evaluated. Contractions may begin and go unrecognized because of the abdominal wall blunting sensation. Special consideration should be given to limiting vasopressors until adequate fluid volume has been replaced. The fetal heart rate should range from 120 to 150 beats/min. Vigilant cardiac monitoring, fetal heart monitoring, oxygen, and intravenous therapy should be continued.

Family visitation in the postanesthesia care unit

The American Hospital Association is promoting patient- and family-centered care and reuniting families with their loved ones in the hospital setting. A growing body of evidence supports visitation in the PACU.61 The American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN) has promulgated a Position Statement on Family Visitation in the PACU (Box 54-1).61 ASPAN advocates a collaborative inclusive approach to keeping families informed by the PACU nurse. Examples of communication include: (1) notification by phone when the patient is admitted and (2) interaction at regular timed intervals throughout the trauma patient’s stay in the postanesthesia unit, which promotes family bonding and coping skills and decreases family anxiety and stress.61 Although this approach may prove challenging, the benefits to the patient and family are numerous.

BOX 54-1 ASPAN’s Position Statement on Visitation in Phase I Level of Care

Background

Position

Guidelines should include the following:

1. Appropriate education for patients and families regarding family visitation to maintain a safe and beneficial experience.

2. The confidentiality and privacy of all patients shall be maintained.

3. The visit will take place at an appropriate time for the patient, visitor, and clinical staff.

4. Perianesthesia nurses should work together with hospital administration to establish a well-organized family visitation program supported by appropriate personnel to meet the needs of families in this unique setting.

From The American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses: A position statement on visitation in phase 1 level of care, Cherry Hill, NJ, 2011, ASPAN. Reprinted with permission.

Summary

Implications for practice

Perianesthesia nurses, who care for massive hemorrhagic and shock in trauma patients in the postanesthesia care unit, need to understand the pathophysiology, implications, and treatment of massive hemorrhage with coagulopathy as the best practice for continued resuscitation of trauma patients.

Source: Spinella PC et al: Warm fresh whole blood is independently associated with improved survival for patients with combat-related traumatic injuries, J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care 66:S69–S76, 2009.

1. Spencer BL, Favand LR. Nursing care on the battlefield. Am Nurse Today. 2006;1:24–26.

2. Nichols DG, et al. Golden hour: the handbook of advanced pediatric life support. ed 3. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2011.

3. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Surveillance summaries. Morbidity Mortality Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1–148.

4. Patel MP, et al. The impact of selected chronic disease on outcomes after trauma: A study from the national trauma bank. Am J Coll Surg.2011;212:96–104.

5. Paulozzi LJ, et al. Recent trends in mortality from unintentional injury in the United States. J Safety Res. 2006;37:277–283.

6. Moore L, et al. Trauma centre outcome performance: a comparison of young adults and geriatric patients in an inclusive trauma system. Injury; March 5, 2011. (epub)

7. Chang DC, et al. Undertriage of elderly trauma patients to state-designed trauma centers. Arch Surg. 2008;243:776–781.

8. Weigelt JA, et al. Mechanism of injury. McQuillan KA, et al. Trauma nursing: from resuscitation through rehabilitation. ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.

9. Mamaril ME, et al. Care of the orthopaedic trauma patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2007;22:184–194.

10. Emergency Nurses Association: Trauma nursing core course. ed 6. Des Plaines, Illinois: Emergency Nurses Association; 2007.

11. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma: Advanced trauma life support for doctors. ed 8. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2008.

12. Von Rueden KT. Shock and multiple organ syndrome. McQuillan KA, et al. Trauma nursing: from resuscitation through rehabilitation. ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.

13. Johnstone RE, et al. Intravenous access. William CW, et al, eds. Trauma: emergency resuscitation, perioperative, anesthesia, surgical management. New York: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc; 2007;vol. 1.

14. DuBose JJ, et al. Clinical experience using 5% hypertonic saline as a safe alternative for use in trauma. J Trauma, Injury, Infection, and Crit Care. 2010;68:1172–1177.

15. Vencenzi R, et al. Small volume resuscitation with 3% hypertonic saline solution decrease inflammatory response and attenuates end organ damage after controlled hemorrhagic shock. The Am J of Surgery. 2009;198:407–414.

16. Scaife ER, Statler KD. Traumatic brain injury: preferred methods and targets for resuscitation. Surgery.2010;22:230–245.

17. Nagele P, et al. Anesthesia and prehospital emergency trauma care. Miller RD, ed. Miller’s anesthesia, ed 7, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2010.

18. Beekley AC. Damage control resuscitation: a sensible approach to the exsanguinating surgical patient. Crit Care Med.2008;36:S267–S274.

19. Stahel PF, et al. Current trends in resuscitation strategy for the multiply injured patient. Injury.2009;4054:S27–S35.

20. Revell M, et al. Endpoints to fluid resuscitation in hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care. 2003;54:S63–S67.

21. Bridges E, Biever K. Advancing critical care. AACN Advanced Critical Care. 2010;21:260–276.

22. Spinella PC, et al. Warm fresh whole blood is independently associated with improved survival for patients with combat-related injuries. Journal of Trauma, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2009;66:S69–S75.

23. Mamaril M. Safety alert: dangerous communication gaps. Breathline. 2006;26:9.

24. Smith BP, et al. Review of abdominal control and open abdomen: focus on gastrointestinal complications. J Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 2010;19:425–435.

25. Pasero C, McCaffery M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011.

26. Bower TC, Reuter JP. Analgesia, sedation, and neuromuscular blockade in the trauma patient. McQuillan KA, et al. Trauma nursing: from resuscitation through rehabilitation. ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.

27. McGuire JM, Burkhard JF. Risk factors for emergence delirium in U.S. military members. J Perianesth Nurs. 2010;25:392–401.

28. Huang YT. Monitoring oxygen delivery in the critically ill. Chest. 2005;128:554S–560S.

29. Cottingham CA. Resuscitation of traumatic shock: a hemodynamic review. AACN Adv Crit Care.2006;17:317–326.

30. Scalea TM, Duncan AO. Initial management of the critically ill trauma patient in extremis. Trauma Q. 1993;10:3–11.

31. Alam HB, et al. Combat casualty care research: from bench to battlefield. World J Surg.2005;9:S7–S11.

32. Rice V. Shock, a clinical syndrome: an update: I: an overview of shock. Crit Care Nurse. 1991;11:20–27.

33. Rice V. Shock, a clinical syndrome: an update: IV: nursing care of the shock patient. Crit Care Nurse. 1991;11:40–51.

34. Rivers EP, et al. Early and innovative interventions for severe sepsis and septic shock: taking advantage of a window of opportunity. CMAJ.2005;173:1–12.

35. Ozawa K. Energy metabolism. In: Cowley RA, Trump BF. Pathophysiology of shock, anoxia and ischemia. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1982.

36. Lee CS. Role of exogenous arginine vasopressin in the management of catecholamine-refractory septic shock. Crit Care Nurse. 2006;26(6):17–23.

37. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Injury in the United States. Chartbook: US Department of Health and Human Services, US Government Printing Office; 2007:49. 2007

38. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Fatal injury reports. available at: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisquars/index.html, 2009. Accessed on June 5

39. Safe Kids Worldwide: Injury trends fact sheet: trends in accidental injury-related death rates among children, (website). available at www.usa.safekids.org/content_documents/Trends_facts.pdf, 2007. Accessed on March 15

40. Wilson MH, Levin-Goodman R. Injury prevention and control. McMillian JA, et al. Oski’s pediatrics principles and practices. ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

41. Mendelson KG, Fallat ME. Pediatric injuries: prevention to resolution. Surgical Clinics of North America.2007;87:207–228.

42. King WK, et al. Child abuse fatalities: Are we missing opportunities for intervention. Pediatric Emergency Care.2006;22:211–214.

43. Karsli C. Airway management. In: Mikrogianakis A, et al. The hospital for sick children manual for pediatric trauma. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

44. Schwengal DA. Initial assessment. Nichols DG, et al. Golden hour: handbook of advanced pediatric life support. ed 3. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2011.

45. Schnur M, Mamaril ME. Pediatric patients. In: Stannard D, Krenzischek DA. Perianesthesia nursing care. Sudbury, Mass: Jones and Bartlett Learning, 2011.

46. Brown HL. Trauma in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009;114:147–160.

47. Burk Sosa ME. The pregnant trauma patient in the intensive care unit: collaborative care to ensure safety and prevent injury. J Perinat Neonat Nurs.2008;22:33–38.

48. John PR, et al. An assessment of the impact of pregnancy on trauma mortality. J Surgery. 2011;1016:94–98.

49. Ruffolo DC. Trauma care and managing the injured pregnant patient. JOGNN.2009;38:704–714.

50. Saunders EE. Screening for domestic violence during pregnancy. Int J Trauma Nurs.2000;6:44–47.

51. Tweddale CJ. trauma during pregnancy. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2006;29:53–67.

52. Ackerson LK, Subramanian SV. Intimate partner violence and death among infants and children in India. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1423–1428.

53. Shah PS, Shah J. Maternal exposure to domestic violence and pregnancy and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19:2017–2031.

54. Muench MV, Canterino JC. Trauma in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34:555–583.

55. Hull SB, Bennett S. The pregnant trauma patient: assessment and anesthetic management. Int Anesthesiology Clinics.2007;45:1–18.

56. Criddle LM. Trauma in pregnancy. AJN. 2009;109:41–47.

57. El Kady D. Perinatal outcomes of traumatic injuries during pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50:582–591.

58. Rudloff U. Trauma in pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276:101–107.

59. Shaver SM, Shaver DC. Perioperative assessment of the obstetric patient undergoing abdominal surgery. J Perianesthes Nurs. 2005;20:160–166.

60. Tsuei BJ. Assessment of the pregnant trauma patient. Injury. 2006;37:367–373.

61. American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses: Perianesthesia nursing standards and practice recommendations 2010– 2012. Cherry Hill, NJ: ASPAN; 2010.