45 Care of the obese patient undergoing bariatric surgery

Bariatrics: Branch of medicine dealing with the causes, prevention, and treatment of obesity.

Biliopancreatic Diversion (BD): Surgical procedure that involves reducing the size of the stomach and allowing food to bypass part of the small intestine to change the normal process of digestion.

Body Mass Index (BMI): A measure of body fat derived from a formula using a person’s weight and height.

Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding (LAGB): One of the most common weight loss surgical procedures, it involves placing an adjustable silicone band around the upper portion of the stomach to restrict the size of the stomach. The band is tightened by adding saline through a port that is placed under the skin in the abdomen.

Malabsorptive Procedures: Weight loss surgeries combining the reduction of stomach size, with redirection of the digestive process causing poor absorption of nutrients and calories.

Metabolic Syndrome: A syndrome characterized by several common factors, including abdominal obesity and insulin resistance in which the body cannot use insulin efficiently.

Morbid Obesity: Generally involves a state of being 50% to 100% over normal weight, being more than 100 pounds (45.5 kg) over normal weight, having a BMI of 40 or higher, or being sufficiently overweight to severely interfere with health or normal function.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA): A sleep-disordered breathing; the risk increases with increased body weight.

Obesity: A condition involving an excess proportion of total body fat. A person is considered obese when his or her weight is 20% or more above normal weight.

Restrictive Procedures: Weight loss surgeries reducing the stomach size limiting the capacity of the stomach to hold food.

Roux-En-Y (RNY): Common gastric bypass surgery that divides the stomach into a small upper pouch leaving a much larger, lower remnant pouch and then rearranges the small intestine into a Y configuration to enable outflow of food from the small upper stomach pouch, via a Roux limb.

Sleeve Gastric Resection (SGR): A newer weight loss surgery that creates a thin, vertical sleeve of stomach using a stapling device, removing the rest of the stomach, thus limiting the amount of food eaten without causing any malabsorption.

Vertical Banded Gastroplasty (VBG): Weight loss surgery also known as stomach stapling, using both a band and staples create a small stomach pouch to restrict food volume.

Weight Loss Surgery (WLS): Procedures that either limit the amount of food a stomach can hold or restrict the amount of food digested.

Obesity is the most common nutritional disorder in the world today. Current estimates suggest that more than one third of the adult population in the United States is affected by excess weight. Approximately 33.3% of adult males, 35.3% of adult females, and 10% to 16.5% of teenagers and children are clinically obese.1 Weight loss surgery is one treatment option for patients who are overweight. Bariatric surgeries increased during 1993 to 2005 from 9189 to more than 140,000 per year.2 Caring for the patient with bariatric concerns presents a number of challenges for the perianesthesia nurse.

Defining obesity

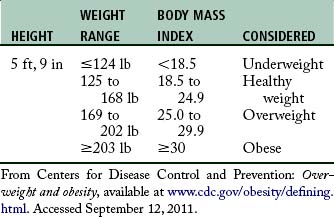

The higher the BMI, the greater the weight associated with a given height (Table 45-1). Recent studies have demonstrated that the patient who is considered overweight and one who is considered moderately obese usually experience minimal risks in the perioperative period.3 Underweight patients, as well as patients with a BMI greater than 30, are found to have increased perioperative mortality rates. Although obesity is not equally distributed across gender or race, the incidence of obesity in a given community is relevant and clinically important. Patients in the obese and morbidly obese categories are seen in perianesthesia services for a wide variety of conditions for a wide variety of services, including surgery.

Physiologic considerations in obesity

Pulmonary

In the general population, undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is common in obese patients despite awareness that increased abdominal girth is a significant risk factor. Reportedly more than 70% of patients undergoing weight loss surgery have been clinically diagnosed with sleep apnea.4 OSA can occur in patients with redundant pharyngeal tissue. Obstructive sleep apnea is characterized by excessive episodes of apnea (approximately 10 seconds), apneic episodes occurring more than five times per hour, and a 50% reduction in airflow or a reduction sufficient to lead to a 4% decrease in oxygen saturation during sleep as a result of a partial or complete upper airway obstruction. Clinically significant apnea episodes of more than five episodes in 1 hour or 30 per night result in hypoxia, hypercapnia, systemic and pulmonary hypertension, and cardiac arrhythmias. In obese patients with OSA, there is an increased risk of difficult intubations as well as postextubation complications.4

Cardiovascular

A positive correlation exists between an increase in body weight and increased arterial pressure. Hypertension is a known risk factor for the development of coronary artery disease. A weight gain of 28 lb (12.75 kg) can increase the systolic and diastolic blood pressure by 10 and 7 torr, respectively. Systemic hypertension is tenfold more likely in the obese patient. The increase in blood pressure is probably caused by the increased cardiac output.

Bariatric procedures

For centuries, standard diet and exercise was the usual prescription for weight loss. With the increase in incidence of obesity and obesity-related health concerns, weight-related issues have become a priority in the health fields and the media. Multiple venues for managing weight have been established and newer, safer techniques in weight loss surgery are among the many treatment options for reducing excess body fat.

Source: Schumann R et al: Best practice recommendations for anesthetic perioperative care and pain management in weight loss surgery, Obes Res 13(2):254−266, 2005.

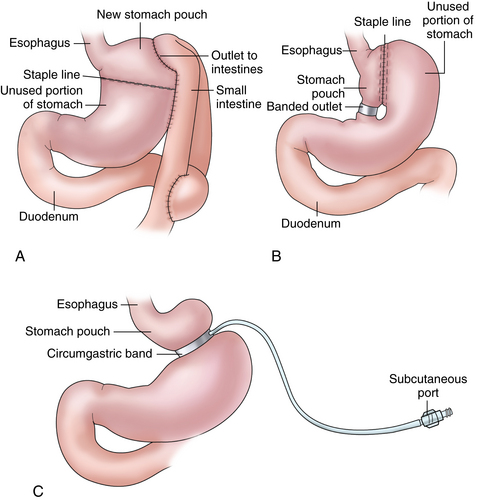

Two of the most common restrictive procedures include the laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB; Fig. 45-1, C) and the vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG; see Fig. 45-1, B). The LAGB procedure involves the placement of an inflatable silicone band around the upper portion of the stomach. When in place, an access port is implanted just under the skin. This port allows for the injection or withdrawal of fluid into the band’s lumen to either increase or decrease the diameter of the band. The end result is a smaller volume of food consumed with an early and longer sensation of fullness.

The most common malabsorptive weight loss procedure is known as the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (see Fig. 45-1, A). Either open or laparoscopic, this procedure involves making the stomach smaller by creating a small pouch at the top of the stomach using surgical staples or a plastic band. The smaller stomach is then connected directly to the middle portion of the small intestine (jejunum), bypassing the rest of the stomach and the upper portion of the small intestine (duodenum). The smaller stomach reduces the amount of food taken in, and the bypass of the intestines result in fewer calories being absorbed.

Perianesthesia care of the obese patient

Equipment

Securing proper equipment throughout the continuum of care for the bariatric patient ensures patient comfort and safety. Properly sized blood pressure cuffs, gowns, bedside commodes, and transfer devices, such as wheelchairs and crutches, may be needed for the morbidly obese patient. In addition, special bariatric beds or stretchers for the operating room and postoperative care are also necessary. Adequate padding should be used to avoid pressure injuries that result in neurologic injury or rhabdomyolysis, a result of compartment syndrome and associated muscle necrosis. Because of problems associated with central lines in these patients, checking with the anesthesia care team to see what monitoring equipment is in use is important so that it can be continued in the postanesthesia phase.

Respiratory

Positioning can be a valuable therapeutic tool for improving arterial oxygenation. Vigorous pulmonary toileting, including coughing, deep breathing, and the use of an incentive spirometer in the awake patient are also important nursing interventions. Position has been shown to significantly affect PaO2 levels for 48 hours after surgery. The obese patient should be cared for in a semi-Fowler position unless cardiovascular instability exists. Routine use of the supine position should be avoided, because the functional residual capacity can decrease to less than the closing capacity and thus reduce the number of ventilated alveoli, which ultimately leads to hypoxemia. Another position that aids in relieving pressure on the diaphragm is the head-elevated laryngoscopy position, which is a modified semi-Fowler position with elevation of the head and upper body with pillows to create a horizontal line between the sternum and ear that also improves the view for reintubation, if needed. Moreover, early ambulation and mobilization in the PACU is of great value in enhancement of lung volumes of the obese patient.

Pain and comfort management

Other comfort measures for the bariatric patient include the prevention of hypothermia. Lowered body temperatures will increase metabolic workload, increase oxygen demand, and ultimately increase the work of the cardiovascular system. Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis requires attention to the proper fitting of compression devices, taking care to avoid a tourniquet effect that can impede blood flow and cause nerve or skin damage. Attention to skin integrity and condition is important for the bariatric patient. In addition to tension on skin during positioning and movement, care should be taken to keep skin clean and dry. Obesity-related stress incontinence is common and should be monitored. Last, close monitoring of serum glucose levels will help to minimize wide variations in blood sugars.

Summary

The prevalence of obesity in patients seeking elective, bariatric, or emergency surgery has undoubtedly increased in recent years. Although patients with mild degrees of obesity pose few additional problems for perianesthesia and surgical management, those with a significant body mass index (BMI) require special consideration, equipment, and handling. Preoperative assessment is a key component of patient safety and preparation. Knowledge of the physiology of obesity is critical to understanding the implications of anesthesia and surgery on the overweight patient. In addition, the choice of anesthesia, patient positioning and handling, and postoperative care all require careful planning.

1. Stewart M. Obesity and the perianesthesia patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2009;24(5):332–334.

2. Tanner BD, Allen JW. Complications of bariatric surgery: implications for the covering physician. The American Surgeon.2009;75:103–112.

3. Mullen JT, et al. The obesity paradox. Annals of Surgery. 2009;250(1):166–172.

4. Schumann R, et al. Best practice recommendations for anesthetic perioperative care and pain management in weight loss surgery. Obesity Research. 2005;13(2):254–266.

Akinnusi ME, et al. Effect of obesity on intensive care morbidity and mortality: A meta-analysis. Crit Care Med.2008;36(1):151–158.

Boeka AG, et al. Psychosocial predictors of intentions to comply with bariatric surgery guidelines. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2010;15(2):188–197.

Buchwald H, et al. Surgical management of obesity. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Flynn DR. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:445–454.

Houston DK, et al. Weighty concerns: the growing prevalence of obesity among older adults. Journal of the American Dietetic Association.2009;109(11):1886–1895.

Ide P, et al. Perioperative nursing care of the bariatric surgical patient. AORN. 2008;88(1):30–54.

Jelic S, et al. Vascular inflammation in obesity and sleep apnea. Circulation. 2010;121:1014–1021.

Lotia S, Bellamy MC. Anaesthesia and morbid obesity. Cont Edu Anesth Crit Care & Pain. 2008;8(5):151–156.

Marley RA, et al. Perianesthesia respiratory care of the bariatric patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2005;20(6):404–431.

McAtee M, Personett RJ. Obesity-related risks and prevention strategies for critically ill adults. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am. 2009;21:391–401.

National Institutes of Health: Bariatric surgery for severe obesity. NIH Publication. 2009;08-4006:1–6. Accessed. http://win.niddk.nih.gov/publications/PDFs/gasurg12.04bw.pdf, April 25, 2012.

Noble KA. The obesity epidemic: the impact of obesity on the perianesthesia patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23(6):418–425.

Pories WJ. Bariatric surgery: risks and rewards. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11):S89–S96.

Reedy S. An evidence-based review of obesity and bariatric surgery. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2009;5(1):22–29.

Schneider M. 11 Anesthesia safeguards for the obese, Outpatient Surgery Magazine. available at www.outpatientsurgery.net/guides/overweight-patients/2008/print&id=6960, August 18, 2011. Accessed

Sharkey KM, et al. Predicting obstructive sleep apnea among women candidates for bariatric surgery. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19(10):1833–1838.

Silk AW, McTigue KM. Reexamining the physical examination for obese patients. JAMA. 2011;305(2):193–194.

Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons: SAGES guideline for clinical application of laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Los Angeles, CA: SAGES; 2008. Accessed. http://www.sages.org/publication/id/30/, April 25, 2012.

Sood J, et al. Anaesthesia for laparoscopic bariatric surgery – our experience. SAARC J Anaseth. 2008;1(1):76–81.

Ward-Smith P. Obesity – America’s health crisis. Urologic Nursing. 2010;30(4):242–245.