55 Care of the intensive care unit patient in the pacu

Extended-Stay ICU Patients: Critically ill surgical patients who have recovered from anesthesia but need to stay in the PACU an extended or prolonged period of time because of the severity of illness or the need to be observed for complications.

Family Presence: Families are provided the opportunity to be present in the PACU with their loved one during life-threatening situations or at the end of life during cardiopulmonary resuscitation or codes.

Intensive Care Unit (ICU): A hospital setting where critically ill patients are provided nursing care.

Intensive Care Unit Boarders: Critically ill surgical patients who have recovered from anesthesia in the PACU. These patientshave been designated ICU status, but do not have an ICU bed and are boarding in the PACU.

Intensive Care Unit Overflow Patients: Patients who have undergone anesthesia for surgical procedures, have recovered in the PACU, and are awaiting transfer to the ICU or SICU.

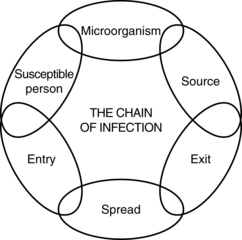

Sepsis: A systemic response to infection.

Septic Shock: Sepsis that progresses to a state of inadequate tissue perfusion characterized by persistent hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation.

Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU): A hospital setting for critically ill surgical patients who need specialized pulmonary, renal, cardiovascular, neurologic, or postoperative monitoring.

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS): A systemic response to infection that involves the activation of the inflammatory response to include change in body temperature, elevated heart rate, respiratory rate, and white blood cell count.

The admission of intensive care unit (ICU) patients to postanesthesia care units (PACUs) is steadily increasing. In addition, the PACU also cares for another type of critically ill surgical patient population: ICU overflow patients, also known as ICU boarding patients. This terminology refers to a unique critical care patient population who recovers in the PACU and subsequently meets the PACU discharge criteria. However, these ICU patients are unable to be transferred because of the unavailability of inpatient ICU beds, subsequently theyremain in the PACU. This increase reflects a nationwide health care dilemma for emergency department and PACU patients who create a high demand for hospital beds. The American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN) Delphi Study identified ICU overflow patients and critical care competencies as the top research clinical, educational, and management priorities.1 Finally, these national patient safety priorities are strategic for ensuring safe, quality postanesthesia care to ICU patients and to the care environment.

Throughout the United States, divergent postanesthesia practices have existed in the provision of care for the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) patient. Operationally, ICU recovery must occur on a routine basis, regardless of prognosis or acuity in the appropriate care setting. Some PACU care of the postsurgical critical care patient may be sporadic or an exception to the norm. From a clinical and an administrative position, however, the PACU must provide the optimal standard of care to SICU patients.2 This chapter discusses the historic significance of critical care recovery, administrative issues in extended ICU care, innovative educational opportunities to ensure competent staff, and clinical strategies in caring for complex, high-acuity, critically ill patients. Because patient safety is essential in providing care to low-volume high-risk patients, complex and highly specialized ICU nursing care concentrates on neurosurgical, burn, and septic management during the postanesthesia period. Ultimately, postanesthesia care must be focused on providing competent care while preventing harm and keeping critically ill patients safe. Finally, when the SICU patient’s condition becomes life threatening, family presence during resuscitation is introduced as an end-of-life nursing intervention that promotes patient-family–centered care.

Historical significance of critical care recovery

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, ICUs emerged in hospitals for close monitoring of critically ill patients. Before that time, the critically ill postsurgical patients received care recovery rooms and inpatient wards. Critical care nursing was conceived to provide a setting in which the most acutely ill and injured patients received concentrated nursing care to enhance survival. Fifty years ago, ICUs were composed of a few specialized beds located at the end of or apart from an existing inpatient unit.3

Administrative issues

Financial constraints

The 1990s brought increased financial constraints on hospitals and increased competitiveness among hospitals. The focus in the 1990s on controlling costs led to a dramatic shift in the types of patients who were admitted to hospitals. Only the sickest patients were eligible for admission, and the length of stay was compressed to the shortest possible time.4 Although hospital population dropped, ICU patient volumes were steadily increasing. Hospital mergers and closings occurred in many cities. During this same time, two significant changes developed: (1) patient acuity of critically ill patients admitted to hospitals increased and (2) the shortage of ICU nurses prompted hospital administrators to close ICU beds. ICU bed closures have had a serious effect on PACUs. PACUs were naturally chosen for critical care overflow because the environment of care included highly technical monitoring and many critical care–educated nursing staff. In addition, the retention of staff in the PACU was much higher with fewer vacancies. This choice seemed the ideal answer to a complex problem. Consequently, the PACUs were increasingly requested for recovery of SICU patients, and in many hospitals the PACU was designated an ICU overflow unit until an ICU bed became available.

Management dilemmas

Nurse managers encounter numerous challenges between competing health care providers that relate to patient placement priority for ICU beds. These challenges are affected by decisions of senior administrators (e.g., chief operating officers, chief nursing officers, departmental medical officers of medicine and surgery, emergency or trauma physicians). The dilemmas faced by managers affect ancillary staff, families, patients, and the PACU staff nurses. The PACU manager is obligated to follow hospital policies and protocols. When senior administrators make decisions in the best interest of the hospital to keep the emergency departments and operating rooms open and to perform surgery for elective surgical cases regardless of high hospital population, the PACU becomes the relief valve for medical center admissions. Often the hospitalized patients who occupy beds in the ICU are not ready for transfer to a lower level of care. This gridlock has a domino effect on the PACU beds. Emergency department patients who need critical care may be given priority status for ICU beds, as may “code” call patients from inpatient units. Some ICUs actually hold beds open for potential code call situations. As the inpatient and ICU surgical cases are completed, they too compete for the PACU available beds. Complications arise if the PACU is still holding ICU patients from the day before or from earlier in the morning. Eventually, the operating room (OR) schedule may grind to a halt because of the ensuing gridlocked beds. In some hospitals, the OR continues to perform surgery on critical care patients, with admission of more ICU overflow patients to an already stressed PACU. These SICU patients become known as boarders, extended stay, or ICU overflow. Patients and families may voice intense dissatisfaction when the PACU is designated for ICU care.2

Recovery of the ICU patient who has an extended stay in the PACU may have serious physician repercussions. Anesthesia providers and surgeons become frustrated because they want to complete the elective surgical schedule. At times, their behaviors may strain relationships with the nurse manager. The lost surgical and anesthesia revenue can threaten the viability of the hospital if surgical cases continue to be delayed or cancelled. University hospitals also have graduate medical education and need to perform a required number of surgical or anesthesia cases per year to qualify for accreditation of the programs.

ICU patients emerging from anesthetic agents frequently request that their families visit in the PACU. Traditionally, PACUs have been considered large open units in which family visitation is severely limited because of other patients emerging from anesthesia. This type of policy can create intense conflict between the nurse and the family. Family expectations of a private room in which families can visit freely are not met. Furthermore, the family’s anxiety increases when the surgeon speaks about the critical nature of the surgery and the need to place the patient in the ICU. Families frequently worry and may perceive the ICU as a sign of impending death, based on past experiences or those of others.5 Understanding what critical care means to patients and families helps the nurse promote positive coping skills. Depending on the patient’s physical condition, effective communication with the ICU patient may be challenging. Barriers to communication can relate to emergence from anesthesia; the patient’s physical status; the existence of endotracheal tubes, which inhibit verbal communication; medications; or other conditions that alter cognitive function.5,6 The critical care patient’s anxiety can increase the stress response and further complicate the patient’s recovery. Patients may consider that they have a right to see and visit with their family and may find significant emotional support for well-being.

Managing and communicating with the ICU families in the PACU can be challenging. Depending on each patient’s diagnosis and acuity, the SICU patient’s family may be in crisis. If the patient’s condition is critical, the family may exhibit a high degree of stress, anxiety, blame, or other disturbing behaviors. Families may be emotional and act out or exhibit disruptive outbursts. The staff nurse may believe that one’s first duty is to provide care to the patient, not to the family. Time can pass quickly for the PACU nurse and not afford the family timely visits. Anxiety and worry mounts for the waiting family as a result of little or no communication and fear of the unknown. The PACU nurse needs to make a conscious effort to effectively communicate with the family in a manner that promotes coping, personal growth, and adaptation to the ICU patient’s critical condition (Box 55-1).7

BOX 55-1 PACU Nursing Actions for Families in Crisis

• Introduce the PACU Scope of Service.

• Assist the family in defining the SICU problem and condition.

• Aid in identifying sources of support for the family during hospitalization.

• Prepare the family for the PACU care environment, especially the effects of patients emerging from anesthesia, respect for other PACU patients, confidentiality, PACU equipment (e.g., cardiac monitors, ventilators, infusion pumps), and purpose of the equipment.

• Communicate with sincerity and compassion about the critical surgery or illness.

• Express confidence in the family’s ability to handle the situation.

• Try to understand the family’s perspective about the patient’s critical condition.

• Use a “one day at a time” approach and avoid encouraging the family to think of the what-ifs of the patient’s long-term outcome.

• Provide opportunities for the patient and family to make choices and feel useful.

• Guide the family in finding therapeutic ways to communicate with the patient.

• Ensure that the family receives information about significant changes in the patient’s condition.

• Allow the family the opportunity to call the PACU and speak to the nurse anytime.

• Advocate adjusting visitation hours to accommodate the family’s needs.

PACU, Postanesthesia care unit; SICU, surgical intensive care unit.

Adapted from Norton C: The family’s experience with critical illness. In Morton PG, et al, editors: Critical care nursing: a holistic approach, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2005, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Staffing issues

The PACU nurses may express feelings of inadequacy related to critical care competencies. A PACU nurse may have no ICU nursing experience or outdated critical care experience. The critical care experience may have been generalized and not specific, or new technology may be foreign. Nurse-to-patient ratios may be exceeded for safe care. The PACU nurse may already be assigned one patient with simultaneous care for a newly admitted ICU patient with an unstable condition, and then family members (frequently numerous) want to be present and are upset because visitation is limited or not allowed. PACU nurses may find themselves in the midst of ethical situations that involve conflict between the needs of the ICU patient’s family members and the preferences of physicians and other health care providers. Consequently, this PACU environment may be chaotic and not conducive for healing. Visitors may perceive the PACU as a suboptimal environment for a loved one. When PACU nursing staff members perceive that safe patient care is becoming jeopardized or high risk, they should consult the nurse manager immediately.

As the nursing shortage in the United States has become more severe, placing ICU overflow patients in the PACU has become a standard of practice rather than being a series of isolated incidents.8 Reports from PACU nurses in different regions of the country have communicated unsafe practices. Postanesthesia nurses turned to their professional organization, the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN), to voice their concerns about serious issues that affected the care they provided to recovering ICU patients in the PACU. The ASPAN Standards and Guidelines Committee conducted a special review of the evidence to identify current nursing practice issues. The following trends in the care of ICU patients in the PACU were identified:

1. Staffing requirements identified for phase I PACUs may be exceeded during times when PACUs are used for ICU overflow patients.2,6

2. The PACU Phase I nurse may be required to provide care to a surgical or nonsurgical ICU patient who has not been properly trained or has not had the required care competencies validated.2,6

3. Phase I PACUs may not be able to receive patients normally admitted from the operating room when staff is used to care for the ICU overflow patients.2,6

4. When the need to send ICU overflow patients to PACU Phase I does not occur regularly, both the PACU and the hospital management may not be properly prepared to handle the admission and discharge of PACU Phase I and ICU patients.2,6

ASPAN invited the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN) and the American Society of Anesthesiologists to address the practice trend of caring for the ICU overflow patient in the PACU and to strategize to promote safe quality care regardless of where the SICU patient recovers from anesthesia. A collaborative position statement was promulgated by these three powerful specialty organizations (Box 55-2).2

BOX 55-2 Joint Statement on ICU Overflow

Background

1. Staffing requirements identified for phase I PACUs may be exceeded during times when PACUs are being used for ICU overflow patients.

2. The Phase I PACU nurse may be required to provide care to a surgical or nonsurgical ICU patient that the nurse has not been properly trained to care for or for which the nurse has not had the required care competencies validated.

3. Phase I PACUs may be unable to receive patients normally admitted from the operating room when staff is being used to care for ICU overflow patients.

4. Because the need to send overflow patients to the Phase I PACU does not occur regularly, both the PACU and the hospital management may not be properly prepared to deal with the admission and discharge of Phase I PACU and ICU patients.

Statement

1. The primary responsibility for Phase I PACU is to provide the optimal standard of care to the postanesthesia patient and to effectively maintain the flow of the surgery schedule.

2. Appropriate staffing requirements should be met to maintain safe competent nursing care of the postanesthesia patient and the ICU patient. Staffing criteria for the ICU patient should be consistent with ICU guidelines based on individual patient acuity and needs.

3. Phase I PACUs are by their nature critical care units, and as such, staff should meet the competencies required for the care of the critically ill patient. These competencies should include, but are not limited to, ventilator management, hemodynamic monitoring, and medication administration, as appropriate to the patient population.

4. Management should develop and implement a comprehensive resource utilization plan with ongoing assessment that supports the staffing needs for both the PACU and ICU patients when the need for overflow admission arises.

5. Management should have a multidisciplinary plan to address appropriate utilization of the ICU beds. Admission and discharge criteria should be used to evaluate the necessity for critical care and to determine the priority for admissions.

From ASPAN, AACN and ASA’s Anesthesia Care Team Committee and Committee on Critical Care Medicine and Trauma Medicine: A joint position statement on ICU overflow patients, September 1999, in ASPAN: Perianesthesia nursing standards and practice recommendations 2010-2012, Cherry Hill, NJ, 2010, ASPAN.

Orientation and basic critical care competencies

The first steps in planning an orientation to the PACU is the interview process and subsequent hiring of the nurse who is motivated to learn many new skills. In addition, the nurse who seeks to be professionally challenged on a daily basis inspires and motivates the critical care preceptor. The PACU should never be viewed as a place to wind down or retire, because nurses with that goal in mind are often immediately disappointed and dissatisfied with their new jobs. Many PACUs prefer to hire nurses with critical care experience. Medical-surgical nurses are also hired, provided that an adequate support system of nursing education exists during orientation and the length of orientation is such that the nurse without prior critical care experience has ample time to master the myriad new skills essential to the new role.

• Cardiac monitoring, rhythm interpretation, electrocardiogram interpretation

• Arterial blood gas interpretation

• Invasive monitoring equipment—the care and the assessment of the patient with:

Orientation should include the essentials of how to care for the patient who has all or some of the invasive monitoring equipment mentioned previously and how to assemble such equipment in preparation for insertion in the PACU. The PACU should have the necessary equipment readily available in the event that a patient’s condition worsens and invasive procedures are to be performed in the PACU.

Advanced critical care concepts

• Frequency of line and tubing changes

• Frequency of endotracheal tube rotation

• Frequency of ICP and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) measurements

• Frequency of measurements (e.g., cardiac outputs and indexes)

• Frequency of weighing the patient

• Frequency of chest radiographs, electrocardiograms, and laboratory studies

• Use of a continuous cardiac output type of PA catheter

• Use of warming devices for intravenous fluids or blood products

• Frequency of, and ability to perform and manage, the calculation of oxygen consumption, oxygen demand, oxygen extraction ratios, and other elements of oxyhemodynamic calculations (“oxy-calcs”)

• Various modes of mechanical ventilation, including pressure-controlled ventilation

• Use of and care of the patient with continuous infusions of muscle relaxants and twitch monitors

• Competency with protocols in the prevention of ventilatory-acquired pneumonia

• Competency/knowledge of protocols in the prevention of deep vein thrombosis

Creating A specialized critical care resource for the PACU

Many PACUs across the country care for ICU patients sporadically. This situation occurs when the hospital census is high or when a surgical emergency presents. Specialized critical care educational resources strategically provide the PACU nurse with expert advisors when the critical time arises. This resourceful method can be accomplished in several ways. First, the PACU can recruit expertise from the unit. Second, the nurse manager may elect to request key leadership staff to orient and become competent and proficient in managing the care of specific patient populations.

Complex specialized critical care in the PACU

Postoperative care of the neurosurgical ICU patient

The reasons for neurosurgical interventions are numerous. Some of the most common neurosurgical procedures that require intensive care monitoring after surgery include aneurysm clipping or coiling, tumor removal or debulking, lobectomy for seizure management, and cranial surgeries to manage increased ICP. The care of the patient who has had a neurosurgical procedure requires an understanding of the goals for the surgical procedure and continuous focused assessment for the presence of subtle neurologic changes in the patient after surgery. Specifically, the nurse should know: (1) the type of surgical procedure the patient underwent, (2) the length of the operative procedure and any known complications during the surgery, (3) the specific region of the brain in which the operation was performed, (4) the preoperative neurologic examination results to allow comparison with postoperative neurologic assessment results, and (5) the neurologic injury that is considered the primary insult and the negative effects of hypoxemia, hypotension, poor cerebral perfusion, hyperglycemia, hypocapnia, and cerebral edema that are responsible for secondary insults to the brain and further compromise to the patient’s recovery.8–11 Primary goals in the immediate phase of perioperative care of the patient focus on preserving cerebral blood flow through blood pressure management, optimizing tissue oxygenation, maintaining normothermia, and effectively treating cerebral edema.

Brief review of intracranial pressure

One of the greatest risks after surgery is increased ICP. Nurses who provide care to neurosurgical patients must be familiar with the pathophysiology of cerebral edema and interventions to attempt to minimize the negative effects of prolonged increased ICP. Cerebral insult of a variety of mechanisms causes chaos inside the cranial vault.8,11 Edema and increased ICP are frequently a consequence of injury.

Intracranial pressure is the pressure normally exerted by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that circulates around the brain and spinal cord and within the cerebral ventricles.11 Normal ICP is 0 to 10 mm Hg; however, 15 mm Hg is often considered the high end of the normal range.8,11 The cranial vault contains three primary elements: brain tissue (80%), CSF (10%), and blood (10%). The Monro-Kellie hypothesis treats the cranial vault as a closed compartment; therefore, if one of these three components increases, reciprocal changes in the other two components must occur to maintain normal ICP.8,11 For example, if brain tissue swells, CSF production is decreased or displaced into the basal subarachnoid cisterns, and the cerebral vasculature constricts to compensate for brain tissue edema.11 Compliance refers to the ability of these compensatory mechanisms to attempt to maintain a steady relationship between volume and pressure within the cranial vault.11 Displacement of CSF and vasoconstriction, howeve is limited and when the limit is reached, ICP increases.

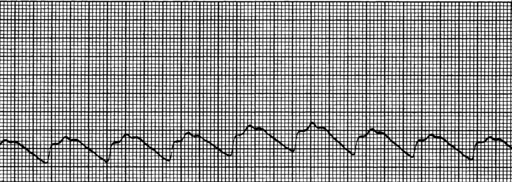

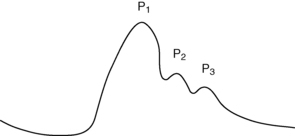

Intracranial pressure can be measured with an intraparenchymal catheter bolt or a ventriculostomy (also called an external ventricular drain [EVD]). Both devises are surgically placed with sterile technique and should be transduced to a monitor to allow assessment of the ICP waveform. The intraparenchymal catheter displays a continuous ICP reading in addition to the ICP waveform. The ventriculostomy can be used to monitor ICP and evacuate CSF. The pulse wave arises primarily from arterial pulsations and to a lesser degree from the respiratory cycle.11 Assessment of the ICP waveform provides valuable clinical information regarding cerebral compliance. The ICP waveform has three peaks known as P1, P2, and P3 (Fig. 55-1). P1 is the percussion wave and originates from pulsations of the arteries and choroid plexus; P2 is the tidal wave and terminates in the dicrotic notch; and P3 is the dicrotic wave, which immediately follows the dicrotic notch.11 The P2 wave is a reflection of intracerebral compliance; a rise in ICP is reflected by a progressive rise in P2 and a concomitant rise in ICP numeric reading on the monitor (Fig. 55-2).11 Analysis of the ICP waveform along with the ICP value and neurologic assessment are used to determine interventions to reduce ICP.

FIG. 55-1 Normal intracranial pressure wave form.

(From McQuillan KA, et al: Trauma nursing: from resuscitation through rehabilitation, ed 4, St. Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

Cerebral edema increases the pressure within the cranial vault, adversely increasing ICP. Cerebral edema may be vasogenic edema, cytotoxic edema, or interstitial edema. Vasogenic edema is an extracellular edema from increased capillary permeability and can develop around tumors or abscesses or with cerebral trauma.11 Vasogenic edema can be treated with osmotic diuretics or, if the cause is tumors, corticosteroids are usually effective.11 Cytotoxic edema occurs during states of poor cerebral perfusion, hypoxia, or anoxic states that cause diffuse cerebral edema. Osmotic diuretics or hypertonic saline solution may be beneficial in treating acute states of cytotoxic edema.10 Interstitial edema occurs with hydrocephalus, and the primary acute intervention is the removal of CSF though an EVD until the condition corrects itself or a surgical shunt is placed.11

CSF is a clear colorless fluid that fills the ventricles of the brain and subarachnoid spaces of the brain and spinal cord. Most CSF is produced by the choroids plexus, which are located in the third and fourth ventricles of the brain. CSF is constantly produced at a rate or approximately 25 mL/h or 500 mL/day.11 When the pressure within the brain exceeds 15 mm Hg, CSF production may slow or the brain displaces CSF to accommodate increases in brain tissue edema. Additional interventions may be the active removal of CSF through an EVD when the ICP exceeds a certain ICP parameter.

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) is the third component of intracranial pressure dynamics. The brain receives approximately 20% of the cardiac output and consumes 20% of the body’s oxygen and 25% of the body’s glucose.8,11,12 When pressures within the cranial vault increase beyond normal ranges, the heart has more difficulty delivering nutrients to the brain. Factors that decrease cardiac output and function, increased blood viscosity, and hypotensive states significantly compromise effective cerebral blood flow. Cerebral vasculature is also influenced by changes in carbon dioxide levels in the blood. High levels of carbon dioxide (i.e., PaCO2) cause cerebral vasculature dilation and increase blood flow, and decreased levels of PaCO2 cause vasoconstriction of cerebral vasculature and decrease blood flow. However, reduction of PaCO2 to less than 35 mm Hg reduces blood flow to the brain tissue and may exacerbate cerebral ischemia, further increasing ICP.10,11 During states of elevated ICP, PaCO2 may be artificially lowered through mechanical ventilation settings that cause hyperventilation to induce cerebral vasoconstriction. However, caution to avoid hyperventilation that lowers PaCO2 less than 35 mm Hg is warranted to avoid worsening cerebral ischemia causing a secondary cerebral insult.

Autoregulation refers to the ability of the brain to maintain a constant CBF despite changes in the arterial perfusion pressure (systemic circulation). Autoregulation is a protective homeostatic mechanism of the brain that attempts to keep cerebral perfusion constant and generally continues to maintain CBF until the ICP exceeds 40 mm Hg.11 Autoregulation provides a constant CBF flow by adjusting the diameter of blood vessels based on changes in the intracerebral pressure. It works synergistically with other protective mechanisms of the brain (e.g., reducing PaCO2 and displacing CSF) to maintain CBF. Autoregulation, however, is limited as a compensatory mechanism. A critical point can be reached because of sustained increases in ICP, global or local diffuse injury, cerebral edema, ischemia, or inflammation.11 If autoregulation is lost, reduced cerebrovascular tone occurs and the CBF becomes dependent on changes in systemic blood pressure. Therefore, a primary goal in management of ICP is effective treatment of the cause of the increase in ICP so that autoregulation is maintained as a compensatory mechanism of CBF.

CPP is a parameter that is calculated from the mean arterial pressure (MAP) minus the ICP and is an indicator of general cerebral perfusion and CBF. Cerebral perfusion pressure becomes increasingly important when the patient loses autoregulatory homeostasis because of sustained increases in ICP. The minimal CPP necessary to maintain adequate perfusion is 50 to 70 mm Hg.11–15 The optimal CPP remains an area of great controversy, and the mechanism of cerebral injury may influence ideal CPP for brain tissue perfusion. Patients with traumatic brain injury may tolerate a CPP of 50 to 70 mm Hg; however, patients with other etiologies (e.g., cerebral hemorrhage) may require a higher CPP threshold.11–15 Because CPP is dependent on MAP, interventions to increase MAP may be necessary if ICP cannot be lowered to maintain effective cerebral perfusion during states of increased ICP. Vasoactive agents to support cardiac output and blood pressure are frequently administered to increase CPP to meet cerebral perfusion demands.

Newer technology can be introduced invasively into the brain and cerebral vasculature to measure brain tissue oxygenation (PtbO2). A brain tissue oxygen probe can be inserted through an intracranial bolt or tunneled and provides information that reflects brain tissue oxygenation associated with cerebral oxygen demand and systematic oxygen delivery.16 A catheter can also be placed in the jugular vein to measure jugular venous oxygen saturation (Sjvo2), which reflects cerebral oxygen demands.17 Neuromonitoring with microdialysis catheters can be used to identify clinical events that precede clinical examination changes.18 A cerebral microdialysis catheter can be inserted through an intracranial bolt and allows sampling of cerebral substances within the interstitial fluid to evaluate the brain metabolism markers (e.g., glucose, lactate, pyruvate, glutamate, glycerol). Evaluation of these markers along with clinical assessment can assist with interventions to prevent secondary brain tissue injury from elevated ICP.18,19

Transient increases in ICP are dynamic temporary increases in ICP. Transient increases in ICP can be caused by coughing, pain, or excessive stimulation. Transient increases in ICP are associated with cerebral hypoxemic and ineffective cerebral perfusion states.11 Signs and symptoms of transient increases in ICP of more than 15 mm Hg include headache, aphasia, changes in respiratory pattern (e.g., Cheyne-Stokes), changes in vital signs, decreases or changes in level of consciousness, motor dysfunction (e.g., hemiparesis), visual disturbances, and nausea and vomiting.11 In addition, sudden diuresis may indicate a dysregulation of antidiuretic hormone related to ICP.

Consequences of increased ICP can be more devastating than the initial neurologic insult.8,11 Nursing interventions need to focus on assessing risk factors for increases in ICP and implementing and monitoring the effects of interventions to reduce sustained increases in ICP.

Postanesthesia management of the neurosurgical patient

Monitoring of ICP, documentation and assessment of the ICP waveform at set intervals, and correlation of the neurologic assessment during elevations in ICP are important nursing assessment interventions. Immediate interventions to reduce ICP include elevating the head of the bed 30 degrees8,20 and maintaining a neutral neck alignment. If noxious stimuli, environmental stimuli, or nursing activities are the cause of increase in ICP, limiting of noxious events such as venipuncture, suctioning, and nursing cares should be considered.

Management of pain and sedation is an important nursing intervention during the perianesthesia care of the neurosurgical patient. Short-acting analgesics and sedation agents should be used to allow continued assessment of the patient’s neurologic status. Maintaining normothermia or inducing mild hypothermia (core temperature, 33° to 36° C) has been found to be neuroprotective in patients with cerebral injury.21 For every decrease in temperature below normal, brain metabolism decreases by 7% to 10%.11,21 Body temperature can be maintained or lowered with conventional air sources, ice, cooling blankets, or intravascular devices. Regardless of the method used to maintain normothermia or mild hypothermia, interventions should not induce shivering. Shivering can adversely increase metabolic demand and oxygen consumption needs beyond the benefits of lowering the patient’s body temperature.

The research on the negative effects of hyperglycemia in critical illness continues to mount. Whereas hyperglycemia can cause adverse patient outcomes, rigorous insulin regimens to maintain tight control of serum glucose can result in hypoglycemia; even transient hypoglycemia can have detrimental effects on patient outcome.22,23,24 Current guidelines recommend a slightly higher serum glucose during critical illness (140 to 180 mg/dL) as studies have that found attempts for tighter glucose control (e.g., 80 to 110 mg/dL) resulted in transient hypoglycemic events.24 Critical illness increases the secretion of counterregulatory hormones, such as glucagon, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and growth hormone; it also results in an increase in hepatic glucose production, decrease in peripheral glucose uptake, and induction of a hyperglycemic state. The hyperglycemia of critical illness is initially an adaptive response to stress; however, over time it exacerbates the circulation of abnormal inflammatory mediators and worsens states of tissue ischemia.23 Glucose is a primary substrate for energy in the brain, and states of both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia have been found to worsen cerebral perfusion.22 Therefore efforts to maintain normoglycemic states (serum glucose, 110 to 180 mg/dL) by administering intravenous insulin either intermittently or via continuous infusion are indicated in the management of the critically ill neurosurgical patient.22

Postoperative care of the ICU burn trauma patient

Unintentional deaths from fire and burns are estimated at 3000 deaths from residential fires and 500 from other sources, including motor vehicle and aircraft crashes and contact with electricity, chemicals, or hot liquids.25 An estimated 75% of these deaths occur at the scene or during initial transport.25 Approximately 450,000 burn injuries require medical attention; 45,000 of these individuals need hospitalization.25 A small percentage of burn-injured patients do not survive (approximately 6%); these patients have associated inhalation injury.26 However, in the face of these sobering facts, the overall mortality and morbidity rates from burn injury have declined over the years because of advances in burn prevention strategies and medical interventions for this patient population. Elements that have been attributed to patient survival include more rapid response by emergency teams, efficiencies in transport to burn treatment facilities, advances in fluid resuscitation, improvements in wound coverage, better support of the hypermetabolic response to injury, advances in infection control practices, and improved treatment of inhalation injuries.27,28

Patients with burn injury have special needs throughout hospitalization. The American Burn Association (ABA) has established guidelines to determine which burn-injured patients should be transferred to a specialized burn center to maximize treatment and decrease patient morbidity and mortality (Box 55-3).29 Patients who meet the criteria outlined by the ABA should be transported to the nearest burn center to maximize patient survival and functional outcome.

BOX 55-3 Criteria for Burn Center Transfer and Referral

• Partial-thickness burns of greater than 10% total body surface area

• Burns that involve the face, hands, feet, genitalia, perineum, or major joints

• Third-degree burns in any age group

• Electrical burns, including lightning injury

• Burn injury in patients with preexisting medical disorders that could complicate management, prolong recovery or affect mortality.

• Any patients with burns and concomitant trauma

• Burned children in hospitals without qualified personnel or equipment for the care of children

• Burn injury in patients who will require special social, emotional, or rehabilitative intervention

From American Burn Association: From Committee on Trauma: Guidelines for the operation of burn centers, resources for optimal care of the injured patient (excerpted), Chicago, 2006, American College of Surgeons, available at www.ameriburn.org/BurnCenterReferralCriteria.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2011.

Brief review of burn injury pathophysiology

Burn tissue injury is associated with the coagulation of cellular protein caused by exposure or contact with heat produced by thermal, electric, chemical, or radiation energy. The depth of coagulative tissue necrosis (depth of burn wound) depends on the intensity of the heat and length of time the tissues are exposed to the heat source. Thermal injury from flame, steam, scald, and contact with hot objects is the most frequent cause of burn injury. Inhalation injury is frequently associated with thermal injury when the victim is trapped in an enclosed space during the fire. Electric injury occurs when electric energy is converted into heat and causes tissue destruction as the current flows through the body. Electric current travels through the body along a path of least resistance, such as nerves, blood vessels, and muscles, sparing the skin except at the entry and exit points of the current resulting in deep internal tissue damage.27,28 Chemical injuries from either acidic or alkaline agents cause tissue destruction related to the type, strength, and duration of contact. Radiation burns are infrequent and usually are the result of medical radiation treatments or industrial accidents.

Regardless of what caused the burn injury, the tissue damage can be conceptualized as having three zones that represent the depth of tissue coagulation. Full-thickness burn is the deepest tissue injury in which full coagulation of the tissue proteins has occurred and causes irreversible tissue necrosis. Immediately surrounding the necrotic tissue area is the region or zone of stasis in which blood flow is impaired.27,28 This region is considered a critical area because it can progress to tissue necrosis if tissue perfusion is inadequate during the burn fluid resuscitation period, which creates a larger burn wound injury. The outer zone of hyperemia has sustained minimal tissue injury and usually heals rapidly. Early goals of burn management focus on stopping the burning process and providing adequate fluid resuscitation to prevent the extension of burn injury from lack of perfusion.

When burn injury occurs, myriad local mediators are released by the body in response to the tissue insult. These mediators—such as histamine, serotonin, prostaglandins, thromboxane A2, kinins, oxygen radicals, platelet aggregation factor, complement cytokines, interleukins, and catecholamines—cause arteriolar and venules dilation, increased microvascular permeability, and decreased perfusion.28,30,31 Proteins leak from the intravascular space into the extravascular space and increase tissue oncotic pressure, creating edema.31 Thromboxane A2, a mediator that causes vasoconstriction, is also released by the body and may compromise perfusion to the burn injury area and cause extension of the depth of burn tissue injury.28,31 Concurrently, the coagulation system is activated, which causes platelet aggregation and activation of polymorphonuclear neutrophil leukocytes and macrophages, which are essential to wound healing. The summation of the activation of the body’s intense inflammatory response is vascular stasis and rapid formation of tissue edema. Edema places the patient at risk of developing intraabdominal hypertension (IAH) that can progress to life-threatening abdominal compartment syndrome.28,30,32 Measurement of intraabdominal pressure via, bladder pressure monitoring may be initiated to evaluate the development of IAH.32 Extensive edema also compromises intravascular fluid volume creating osmotic and hydrostatic pressure changes, often necessitating continued fluid resuscitation to meet tissue perfusion needs that exacerbates edema formation, creating a clinical challenge for optimal fluid volume replacement that minimizes edema formation.

Effective fluid resuscitation is an initial priority to prevent burn shock and progression of tissue injury. Several formulas can be used to guide fluid resuscitation needs based on the patients total body surface area (TBSA) injured. One of the more common formulas used to calculate fluid volume resuscitation is the Parkland formula (Box 55-4). Regardless of the formula used, the goal is to support the circulatory system throughout the initial 24 to 48 hours following the burn injury.33 Fluid shifts are significant during early resuscitation, requiring ongoing evaluation of tissue perfusion (e.g., heart rate, blood pressure, urine output, serum lactate levels) and assessment of complications from edema formation (e.g., IAH and compartment syndrome). Optimal fluid for resuscitation remains a topic of significant research. Fluids for resuscitation include crystalloids (typically lactated Ringer solution), hypertonic saline, and colloids (e.g., albumin, fresh frozen plasma).33 A critical balance is needed to provide optimal fluid resuscitation to meet tissue and organ perfusion needs without inducing secondary complications associated with overresuscitation and edema.

In addition, the extensive loss of tissue and the exaggerated physiologic inflammatory and stress response associated with the burn injury place the patient at risk for infection, hypothermia, hypercatabolism, and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), acute kidney injury (AKI), and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.34–36 The intensity of the hypermetabolic changes experienced by burn patients is directly related to the extent of injury.35 Metabolic demands increase by an estimated 30% in patients with an injury that covers 20% of the TBSA or more and by 100% in patients with burns that cover 50% of the TBSA or more.35,37 Meeting nutritional goals is essential because 10% loss of total body mass leads to immune dysfunction, 30% leads to decreased wound healing, and 40% loss leads to death.35 Efforts to attenuate the hypermetabolic response in critically ill burn patients may include beta-adrenergic blockage with propranolol.35 Other pharmacologic anticatabolic therapies include growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor, intensive insulin therapy, and oxandrolone.35,37

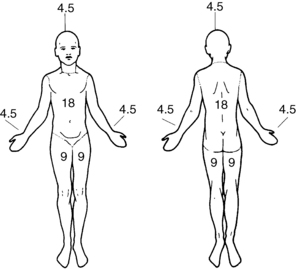

Extent and depth of tissue injury

Burn injuries are described according to the extent and depth of tissue injury. Extent is the TBSA that has been injured, and depth is the severity of tissue necrosis. The rule of nines is a quick and easy method of estimating TBSA (Fig. 55-3). Using this method, the body is divided into seven areas that represent 9% or a multiple of 9% of the body surface area, with the remaining 1% representing the genitalia. This method is most frequently used in the emergency room or upon initial assessment of the burn injured patient to estimate TBSA needed in calculated fluid resuscitation needs for the patient.27 When the patient is in the acute care setting, the percentage of TBSA is more precisely calculated with the Berkow38 and Lund-Browder39 formulas. This assessment tool is used to estimate the amount of tissue injured by the thermal agent. The primary goal in estimating the TBSA of burn injury is to predict: morbidity or survival, physiologic response in relation to fluid shifts, fluid resuscitation requirement, and metabolic and immunologic responses.

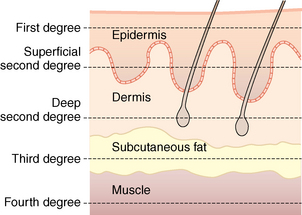

Burn wound depth describes tissue damage based on anatomic loss of the layers of the skin. Depth is estimated from the most external layers of the skin to the internal. Fig. 55-4 depicts the anatomic depth and nomenclature used to describe burn wound depth. Deep partial-thickness and full-thickness burn wounds require tissue grafting for effective healing, cosmesis, and prevention of infection with removal of devitalized tissue. Assessment of burn wound depth may occur several times in the initial 48 hours of admission as burn wounds may progress or extend to deeper layers of the skin in the early days post injury.

Surgical and postanesthesia management of the burn-injured patient

Current management involves the early excision of eschar (necrotic tissue) of deep partial-thickness and full-thickness burn wounds.30 Early surgical debridement is thought to decrease bacterial load, release of inflammatory mediators, and lower the risk of SIRS and sepsis complications.30,40 The goal of surgery is to remove most of the devitalized tissue and cover wounds with either autografts or biologic or synthetic dressings that promote wound healing and closure. The operative plan involves removal of devitalized tissue and an evaluation of the wound bed before application of an autograft or synthetic dressing. If an autograft is used to cover the burn wound, it is important to realize that the donor site for the autograft tissue is also a wound that requires observation after surgery. Physician orders and postoperative notes identify the surgical procedure (e.g., excision, debridement, grafting technique) and type of wound coverage place on the burn wound.

Other priorities focus on ensuring adequate fluid perfusion though effective management of intravenous fluids and vasoactive agents as needed. Efforts to maximize perfusion are necessary to enhance effective blood flow to the tissue bed. Evaluation of blood loss from the surgical procedure and insensible loss from the dressings need to be assessed, and blood products or fluids are adjusted to maintain mean arterial pressure greater than 70 mm Hg and urine output greater than 0.5 mL/kg/h.34 Continuous heart rate monitoring and trends are helpful in monitoring the cardiovascular response after surgery. The heart rate may be falsely elevated from a catecholamine response to the burn injury and surgery; however, changes in heart rate can be used to evaluate effectiveness of fluid replacement interventions.27 Other invasive parameters such as pulmonary artery wedge pressure, stroke volume assessment, and mixed venous oxygen saturation may also provide helpful assessment data to evaluate effectiveness of tissue perfusion.33,41,42 Caution should be used in evaluating fluid volume replacement needs based on central venous pressure readings. Current evidence suggests that central venous pressure readings alone might not adequately reflect the vascular volume status (e.g., hypovolemia or hypervolemia) in guiding fluid resuscitation needs.42 Acid-base balance and serum lactate levels can also provide valuable information on the effectiveness of fluid resuscitation after surgery and tissue perfusion. A base deficit and elevated serum lactate are markers of metabolic acidosis and corrects to normal with adequate resuscitation. A base deficit of 5 mEq/L or more and serum lactate greater than 2.0 are indicators of shock and have been associated with increased mortality.41

Patients with electrical burn injury need additional attention and monitoring of heart rate and rhythm. As voltage passes through the patient’s body, damage to the myocardial system is possible. These patients should receive continuous cardiac monitoring for up to 72 hours to assess for conduction disturbances and myocardial damage.27 Typically, if dysrhythmias occur, they are seen in the first few hours after injury. Myoglobinuria, however, is a serious complication that must be assessed and treated in electrical burn–injured patients. Therefore fluid resuscitation to support the patient’s perfusion and additional fluid to clear the kidneys of myoglobin are necessary during the postanesthesia period. Urine output of 75 to 100 mL/h or 1 to 2 mL/kg/h is usually necessary to treat myoglobinuria.33,34

Pulmonary assessment involves management of the ventilator to maximize oxygenation and ventilation. Third spacing and edema place the burn patient at risk for ARDS. Nursing interventions that monitor the ventilatory management of the patient, airway pressures, patient’s tolerance of the ventilatory mode, and oxygenation parameters are important aspects of nursing care after surgery. The nurse should assess for early signs of ARDS by evaluating the patient’s ventilatory airway pressures, changes in tidal volumes, and signs and symptoms of hypoxemia. The patient may need sedation or neuromuscular blocking agents to assist with ventilator efforts as the ARDS progresses. Newer mechanical ventilation modes, specifically high frequency percussive ventilation, may be initiated as a salvage option for refractory ARDS and treatment of inhalation injury. 43 Pneumonia is a serious complication in a burn-injured patient. Nursing interventions to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia are essential. Nursing interventions include assessment of the head of bed greater than 30 degrees; frequent oral care and toothbrushing with oropharyngeal suctioning; assessment of cuff pressure of the endotracheal tube; and assessment of enteral tube feeding tolerance.44 Patients with inhalation injury are at greater risk of developing ARDS and pneumonia because of the direct injury to the lung parenchyma. Inhalation injury frequently requires more aggressive fluid resuscitation to support systemic perfusion; however, this may increase pulmonary third spacing. Serial bronchoscopy is frequently performed to evaluate the severity of inhalation injury, and aggressive pulmonary suctioning is usually needed to assist with removal of debris and secretions.

Prevention of hypothermia and adverse effects of hypothermia such as electrolyte imbalances, tissue vasoconstriction, and coagulopathies are additional areas for nursing care focus.21 Application of convection air heating devices and thermal hats and warming of the patient’s room can assist with preventing hypothermia. Care is needed, however, to prevent overshoot that causes hyperthermia. The burn patient cannot effectively regulate body temperature because of the tissue loss; therefore external temperature changes can greatly influence the patient’s body temperature.

Maintenance of nutritional management through surgery and after surgery is also a standard of care in the management of the burn patient. Typically the patient has a postpyloric feeding tube in which low-dose continuous tube feeding is provided to the patient, including during the perioperative procedure.37 Hypermetabolism associated with burn injury requires significant nutritional replacement strategies to meet metabolism demands and provide substrates for tissue healing.

The final nursing priority is effective management of pain. Burn-injured patients have hypermetabolism in response to the injury and ongoing insults with surgical management for burn wound excision and wound coverage. Opioid infusions, usually morphine or fentanyl, are the mainstay for treating pain. The addition of continuous or intermittent (scheduled) anxiolytic agents is also beneficial with pain management.27,45 Evidence-based pain assessment tools are needed to assess a patient’s pain, and the patient may have a difficult time obtaining pain relief during the immediate postanesthesia period. Burn patients frequently have a tolerance to analgesic agents; therefore continuous infusions of analgesics and sedation agents titrated to desired pain and sedation responses for the patient provide optimal management after surgery. Efficacious postanesthesia management of the critically ill, burn-injured patient plays a vital role in the functional outcome and future rehabilitation.

Postoperative care of the septic ICU patient

Patients admitted and treated for sepsis in the emergency department, inpatient medical-surgical unit, or ICU is often transferred to the OR for surgery. The initial presentation is often nonspecific, and the severity may be deceiving. Critical illness may often be accompanied by localized or systemic infection. Patients may arrive with a relatively benign diagnosis, or clinically unapparent infection can progress within hours to a more devastating form of disease.46 Sepsis is an acute systemic response to a bacteria invasion or to the toxins produced by bacteria (Box 55-5); it is associated with SIRS.47 Dellinger and colleagues47 provided clinical definitions of SIRS, sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock. Although sepsis can occur from infection by gram-positive or yeast infections, the most common cause is from gram-negative endotoxins. With system infection, myriad cellular, humoral, and immunologic defense systems initiate a cascade of mediator-induced responses. With sepsis, this inflammatory response is exaggerated, creating the complex clinical presentation of activation of neutrophil, inflammation, increased vascular permeability, platelet aggregation and destruction, and vasoconstriction. Cellular and humoral mediators such as lipoteichoic acid, leukotrienes, cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukins, prostaglandins, histamine, serotonin, complement, thromboxane A2, and arachidonic acid metabolites are mediators known to be responsible for the overwhelming systemic response seen with sepsis and SIRS.48 Research continues to identify additional mediators and their actions. Serum marker of inflammation to include C-reactive protein and procalcitonin are also an area of active research exploring the variation in these markers and a patient’s inflammatory responses during sepsis.49,50

BOX 55-5 Consensus Definitions

Bacteremia: The presence of viable bacteria within the blood.

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS): The presence of altered organ function in a patient who is acutely ill and in whom homeostasis cannot be maintained without intervention.

Sepsis: The presence of infection associated with SIRS. SIRS plus the clinical presence of one manifestation:

Septic Shock: A state of acute circulatory failure characterized by persistent arterial hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation or tissue hypoperfusion unexplained by other causes.

Severe Sepsis: Sepsis complicated by end-organ dysfunction.

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome: Systematic response to infection with the presence of two of the following clinical findings:

From Dellinger RP, et al: Surviving sepsis: campaign guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock, Crit Care Med 32:858–872, 2004.

The key to treating septic patients is early identification and aggressive treatment of the suspected cause.41 Patients at highest risk of sepsis include very young and older patients and patients with chronic illness, immunosuppression, exposure to infection, and invasive procedures.51 Implementation of early sepsis recognition and treatment protocols is needed to reduce the morbidity and mortality of patents with sepsis.52, 53

Pathophysiology and management of sepsis and septic shock

The key to understanding septic shock is the profound hemodynamic instability. The nurse may witness two different dysfunctional patterns of the cardiovascular system as a consequence to sepsis. The first is characterized by high cardiac output and low systemic vascular resistance, and the second reveals a more classic shock with low cardiac output and high systemic vascular resistance.51 These two clinical findings reflect a hyperdynamic or hypodynamic shock state. The hyperdynamic response is termed early septic shock, and the hypodynamic response is the late septic shock that indicates a severe septic shock and is not reversible.

Activation of a SIRS and subsequent mediator release creates the complex clinical presentation of profound vasodilation and increased capillary permeability that manifests as hypotension. Activation of the complement cascade causes mast cells to degranulate liberating histamine, resulting in local vasodilation and capillary permeability. Neutrophil activation initiates synthesis of leukotrienes and oxygen free radicals, also increasing permeability and bronchoconstriction. Platelet aggregation in the microvasculature obstructs flow, perpetuating an inflammatory response to injury. Platelet consumption also ensues, causing coagulopathies and ultimately profound thrombocytopenia.51

Treatment of hypoperfusion associated with sepsis focuses on aggressive fluid resuscitation and early diagnosis and source identification to include obtaining blood cultures prior to antibiotic administration.53 Fluid resuscitation with crystalloid or colloid agents should occur as soon as possible in patients with hypotension or elevated serum lactate. A fluid challenge of 1000 mL of crystalloids or 300 to 500 mL of colloids over 30 minutes should be given initially to treat sepsis-induced tissue hypoperfusion.53 Continued fluid resuscitation goals include: (1) central venous pressure of 8 to 12 mmHg, (2) mean arterial pressure ≥65 mmHg, (3) urine output ≥0.5 mL/kg/h, and (4) central venous oxygen saturation ≥70% or mixed venous oxygen saturation ≥65%.53 Vasopressor agents such as norepinephrine or dopamine centrally administered may need to be added to increase blood pressure. Epinephrine, phenylephrine, or vasopressin should not be administered as the initial vasopressor agent in patients with septic shock.53 Vasopressin (0.03 units/min) may be added to norepinephrine infusion.53 Inotropic support may be indicated to augment cardiac function.

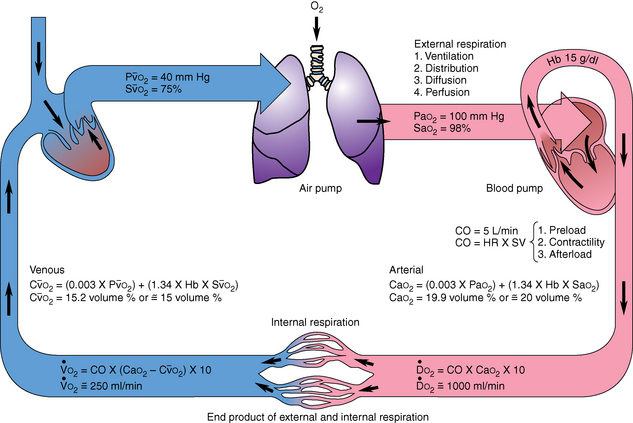

Pulmonary dysfunction

The lung is one of the primary target organs in sepsis. Transport and utilization of oxygen at the cellular and tissue levels are vital for survival (Fig. 55-5). ARDS is associated with an oxygen extraction defect that affects the utilization and delivery of oxygen to the tissues. The subsequent formation of interstitial edema contributes to the inability to extract oxygen. In addition, the release of inflammatory mediators damages the endothelium of the pulmonary vasculature and increases the permeability of the alveolar-capillary defect, resulting in ventilation–perfusion mismatch and impaired gas exchange.51 Changes in lung compliance and impaired gas exchange are two pathophysiologic abnormalities that can lead to ARDS. Protracted oxygen debt can result in the development of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and eventual organ death.54

FIG. 55-5 Oxygen transport.

(From Copstead LE, Banasik JL: Pathophysiology, ed 4, St. Louis, 2010, Saunders.)

The goals of managing septic patients with ARDS are maximizing pulmonary gas exchange, optimizing oxygen delivery to the tissues, and preventing further organ injury. Mechanical ventilation or noninvasive ventilation may be needed to assist with oxygenation and effective ventilation. Positive end-expiratory pressure can be used to avoid extensive lung collapse at end expiration.53 The PACU nurse’s role in ongoing vigilant assessments, interventions, and monitoring that help to promote improved gas exchange and reduced oxygen demands provides a crucial key to better survival rates.

Metabolic dysfunction

The metabolic derangements that accompany septic shock are dependent on the severity and duration of the illness that result in intensified transport and perfusion problems. Some of these abnormalities are manifested by: (1) mechanical obstruction of capillary beds by platelet aggregation, (2) vasoconstriction that causes shunting formation in the organs, (3) inflammatory mediator interaction, and (4) impaired cellular oxidative metabolism or oxygen debt to the tissues.54 Increased lactic acidosis is persistent even though oxygen consumption is consistently increased. Patients in septic shock need higher oxygen delivery because of the escalating metabolic demand. Sustained proteolysis is evidenced by high urinary nitrogen excretion.54 Gluconeogenesis is increased; however, concurrent insulin resistance results in hyperglycemia in the hyperdynamic state of septic shock. In late septic shock, a profound hypoglycemia develops as glycogen stores are depleted and are insufficient to supply the body’s demands.

Steroid therapy

In the neurohumoral response to septic shock, many patients have an inadequate adrenal reserve. Although the physiologic mechanism is not fully understood, it is likely caused by the inflammatory cascade that leads to inadequate release of adrenocorticotropin. Intravenous hydrocortisone may be considered in adult septic shock patients when hypotension responds poorly to aggressive fluid and vasopressor support.53 An adrenocorticotrophin hormone level is not recommended before administering hydrocortisone.53.The recommended hydrocortisone dose is ≤300 mg/day, and therapy can be weaned when vasopressor agents are no longer needed to support the patient’s blood pressure.53

Glycemic control

As discussed previously, tight glycemic control (serum glucose of 80 to 100 mg/dL) is no longer recommended, because hypoglycemic events associated with regulating tight control in critically ill patients have been found to result in adverse patient outcomes.55 Current evidence suggests maintaining serum glucose between 140 to 180 mg with aggressive insulin therapy and close monitoring indicated in the management of the critically ill septic patient.24

Acute kidney injury

AKI is often associated with sepsis and septic shock. Generally, two pathophysiologic causes are cellular ischemia related to hypoperfusion and the presence of SIRS. Mediators of inflammation, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6, influence the perfusion to the kidneys and cause damage to the renal tubules.54 Because the cause of AKI is inadequate renal perfusion, often related to deficits in intravascular volume, prompt replacement of crystalloids, colloids, and blood is warranted.41 Low-dose dopamine (1 to 3 mcg/kg/min) does not provide renal protection and should not be administered.56 Management of acid-base, cardiovascular, and intake and output alterations is vital in preserving kidney function and preventing organ failure in the septic patient.54

Postanesthesia management of the patient in septic shock

Advances continue in early identification and aggressive treatment of patients with sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock .The surviving sepsis campaign (www.survivingsepsis.org) provides a comprehensive, evidence-based guideline to assist clinicians in the management of severe sepsis and septic shock.

Postanesthesia care of the patient in septic shock must first focus on fluid resuscitation and identification of possible cause. Peripheral vasodilation, hypotension, and myocardial depression can significantly impede tissue perfusion. End-organ perfusion should be monitored with assessment of skin temperature, color, capillary refill, and peripheral pulses every hour. Because of mediators of inflammation, vasopressor and inotropic agents may be needed, in addition to aggressive fluid resuscitation, to support tissue and end-organ perfusion. Blood product administration may be indicated if the patient has a hemoglobin less than 7.0 g/dL, with a goal of transfusing to a hemoglobin of 9.0g/L.53 Tachycardia should be assessed, and interventions to keep the heart rate at less than 100 beats/min should be initiated.

Interventions to maximize oxygenation and ventilation are concurrently necessary to ensure that cellular oxygen delivery and consumption needs are being met. The patient may need frequent suctioning to remove secretions and careful monitoring of blood gases. Because ARDS frequently accompanies sepsis, the patient may need mechanical ventilation. Lower tidal volumes (6 mL/kg of estimated body weight) is the current recommendation for patients requiring mechanical ventilation, because lower tidal volumes result in less barotrauma.53 The PACU nurse should frequently monitor the septic patient for decreased pulmonary compliance associated with airway hyper-reactivity or pulmonary consolidation, which further impairs ventilation.57

Sepsis management implications for the PACU nurse

Management of the septic critically ill patient in the PACU can be challenging, even to the most experienced critical care nurse. The high mortality rate of septic shock emphasizes the importance of preventing and reversing the rapid progression of the disease.41,51,53 Effective postanesthesia nursing care mandates knowledge of current sepsis research related to pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of SIRS. An understanding of the process of sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock sequelae is imperative. The PACU nurse must have a high degree of suspicion when the etiologies that predispose sepsis are seen in the recovering patient. Likewise, monitoring of the ICU patient vigilantly for signs and symptoms of decreased cardiac output and alterations in oxygenation and tissue perfusion provides key assessment information. Furthermore it is necessary to report, in a timely manner, the subtle but significant critical changes in the patient’s condition to the surgeon, anesthesia provider, or intensivist. New advancements in sepsis therapies should be used as evidence-based practice guidelines to care.

Family presence during resuscitation

The impressive expertise of postanesthesia nurses is often taken for granted by both the nursing staff members and medical colleagues.58 The staff members expect the patients under their care to do well. However, what does the staff do when the patient’s condition becomes life threatening or even fatal? What happens in the PACU when things go wrong? Are these specialty nurses prepared for end-of-life nursing interventions? PACU nurses must become knowledgeable about the current evidence that emphasizes not only the needs of the patients, but more importantly the needs of the surviving families.

Source: Dollin CT, et al: Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: using evidence-based knowledge to guide the advanced practice nursing in developing formal policy and practice guidelines, J Am Acad Nurse Pract 23:8–14, 2011; Halm MA: Family presence during resuscitation: a critical review of the literature, Am J Crit Care 14:494–511, 2005.

The presence of a patient’s family during resuscitation is emerging as an acceptable practice in the critical care setting. Critical care and emergency department nurses have been leaders in advocating family presence during resuscitation. In the landmark article of 2001 entitled Family Presence During Invasive and Resuscitation: Hearing the Voice of the Patient, the authors reported an NBC Dateline poll that showed 74% of 2464 respondents believed family members should be allowed to be in an emergency department during invasive procedures.59 Current evidence supports the multiple benefits of this practice to patients, families, and health care providers.58–63 Patients believe that family presence gives them the feeling of support, personhood, connectedness, and advocacy.61,63 Research has repeatedly revealed that families have specific needs that include: (1) having honest, consistent, and thorough communication with health care providers; (2) being physically and emotionally close to their loved one; (3) feeling that the health care providers care about their loved one; and (4) visiting the patient frequently during a health-related crisis.64 Both patients and families believe that they have a right to have families present during resuscitation.65 Health care providers agree that family presence encourages professional behavior of staff at the bedside and facilitates end-of-life closure issues for families.64–68 The Emergency Nurses Association and the AACN have issued position statements in support of family presence during resuscitation.69,70 PACU nurses need to expand their knowledge of family presence during resuscitation and adopt a holistic framework that provides the best possible outcomes for patients and families during the end of life.

The PACU nurse must remember the family when resuscitating an ICU patient in the PACU. The benefits far outweigh the risks in implementing family presence in the PACU. Research reveals that families perceive that: (1) they have been supported, (2) everything was done for the patient, (3) patient-family connectedness was maintained, (4) the patient’s personhood was respected, and (5) they coped better with death.61–64

1. Mamaril M, et al. ASPAN’s Delphi study on national research: priorities for perianesthesia nurses in the United States. J Perianesth Nurs.2009;24:4–13.

2. American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses: Perianesthesia nursing standards and practice recommendations 2010-2012. Cherry Hill, NJ: American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses; 2010.

3. Fontaine DK. Impact of the critical care environment on the patient. Morton PG, et al. Critical care nursing: a holistic approach. ed 9. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

4. Ayres SA, et al. Care of the critically ill, ed 3. Chicago: Yearbook Medical Publishers; 1988.

5. Bizek KS. The patient’s experience with critical illness. Morton PG, et al. Critical care nursing: a holistic approach. ed 9. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

6. Norton C. The family’s experience with critical illness. Morton PG, et al. Critical care nursing: a holistic approach. ed 8. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

7. Johannes MS. A new dimension of the PACU: the dilemma of the ICU overflow patient. J Perianesth Nurs.1994;9:297–300.

8. Bader MK. Gizmos and gadgets for the neuroscience intensive care unit. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006;38:248–260.

9. Saiki RL. Current and evolving management of traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am. 2009;21:549–559.

10. Inoue K. Caring for the perioperative patient with increased intracranial pressure. AORN J. 2010;91:511–518.

11. Hickey J, Olson DM. Intracranial hypertension: theory and management of increased intracranial pressure. Hickey JV, ed. The clinical practice of neurological and neurosurgical nursing, ed 6, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.

12. Bershad EM, et al. Intracranial hypertension. Semin Neurol. 2008;28:690–702.

13. Slazinski T. Intracranial bolt and fiber optic catheter insertion (assist), intracranial pressure monitoring, care, troubleshooting, and removal. Weigand D, ed. AACN procedure manual for critical care, ed 6, St. Louis: Elsevier, 2011.

14. Bratton SL, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury: a joint project of the Brain Trauma Foundation. J Neurotrauma.2007;24(Suppl1):S1–S106.

15. Li LM, et al. The surgical approach to the management of increased intracranial pressure after traumatic brain injury. Anesthesia-Analg. 2010;111:736–748.

16. Maloney-Wilensky E. Brain tissue oxygen monitoring: insertion (assist) care and troubleshooting. Weigand D, et al. AACN procedure manual for critical care, ed 6, St. Louis: Saunders, 2011.

17. Slazinski T. Jugular venous oxygen saturation monitoring: insertion (assist), patient care, troubleshooting, and removal. Weigand D, ed. AACN procedure manual for critical care, ed 6, St. Louis: Saunders, 2011.

18. Presciutti M, et al. Neuromonitoring in intensive care: focus on microdialysis and its nursing implications. J Neurosci Nur.2009;41:131–139.

19. Timofeev I, et al. Cerebral extracellular chemistry and outcome following traumatic brain injury: a microdialysis study of 223 patients. Brain.2011;134:484–494.

20. Fan J. Effect of backrest position on intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure in individuals with brain injury: a systematic review. J Neurosci Nurs.2004;36:278–288.

21. Niklasch DM. Induced mild hypothermia and the prevention of neurological injury. J Infus Nurs. 2010;33:236–242.

22. Godoy DA, et al. Treating hyperglycemia in neurocritical patients: benefits and perils. Neurocrit Care.2010;13:425–438.

23. Moghissi ES. Revisiting inpatient hyperglycemia: new recommendations, evolving data and practice implications for implementation. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine LLC, and Global Directions in Medicine, Inc; December 2009.

24. Kavanagh BP, McCowen KC. Glycemic control in the ICU. New England Journal of Med. 2010;363:2540–2546.

25. American Burn Association: Burn incidence and treatment in the United States: 2011 fact sheet. available at: www.ameriburn.org/resources_factsheet.php, May 20, 2011. Accessed

26. Colohan SM. Predicting prognosis in thermal burns with associated inhalation injury: A systematic review of prognostic factors in adult burn victims. J Burn Care Res.2010;31:529–539.

27. Makic MBF, Mann E. Burn injuries. McQuillan K, et al. Trauma nursing from resuscitation through rehabilitation, ed 4, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009.

28. Kramer GC. Pathophysiology of burn shock and burn edema. Herndon D, et al. Total burn care, ed 3, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

29. American Burn Association: Burn Center Referral Criteria. available at: www.ameriburn.org/BurnCenterReferralCriteria.pdf /, March 1, 2012. Accessed

30. Chipp E, et al. Sepsis in burns. Annals of Plastic Surg. 2010;65:228–236.

31. Shupp WJ, et al. A review of the local pathophysiologic basis of burn wound progression. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:849–873.

32. World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome: Consensus definitions and recommendations. available at: www.wsacs.org/consensus.php, May 20, 2011. Accessed

33. Warden GD. Fluid resuscitation and early management. Herndon D, ed. Total burn care, ed 3, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

34. Brusselaers N, et al. Outcome of acute kidney injury in severe burns: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med.2010;36:915–925.

35. Gauglitz GG, et al. Burns: Where are we standing with propranolol, oxandrolone, recombinant human growth hormone and the new incretin analogs. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care.2011;14:176–181.

36. Sheridan RL, Tompkins RG. Etiology and prevention of multisystem organ failure. Herndon D, ed. Total burn care, ed 3, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

37. Norbury WB, Herndon DN. Modulation of the hypermetabolic response after burn injury. Herndon D, ed. Total burn care, ed 3, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

38. Berkow SG. A method for estimating the extensiveness of lesions (burns and scalds) based on surface area proportions. Arch Surg. 1924;8:138–142.

39. Lund CC, Browder NC. Estimation of areas of burns. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1944;79:352–357.

40. Bessey PQ. Wound care. Herndon D, ed. Total burn care, ed 3, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

41. Funk D, et al. A systems approach to the early recognition and rapid administration of best practice therapy in sepsis and septic shock. Curr Opin Crit Car. 2009;15:301–307.

42. Marik PE, et al. Does central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? A systematic review of the literature and the tale of seven mares. Chest. 2008;134:172–178.

43. Allan PF, et al. High-frequency percussive ventilation revisited. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:510–520.

44. Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Prevent ventilator associated pneumonia. available at: www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/Campaign/VAP.htm, May 20, 2011. Accessed

45. Meyer WJ. Management of pain and other discomforts in burned patients. Herndon D, et al. Total burn care, ed 3, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

46. Rivers EP, et al. Early innovative interventions for severe sepsis and septic shock: taking advantage of the window of opportunity. Can Med Assoc.2005;173:1054–1065.

47. Dellinger RP, et al. Surviving sepsis: campaign guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med.2004;32:858–872.

48. Pinksy MR. Septic shock, Medscape Drugs, Conditions and Procedures. available at emedicine.medscape.com/article/168402-overview, May 20, 2011. Accessed

49. Becker KL, et al. Procalcitonin in sepsis and systemic inflammation: a harmful biomarker and a therapeutic target. Br J Pharm.2010;159:253–264.

50. Pierrakos C, Vincent JL. Sepsis biomarkers: a review. available at. Critical Care. 2010;14:1–18. ccforum.com/content/14/1/R15. Accessed May 20, 2011

51. Latto C. An overview of sepsis. Dimension in Critical Care Nurs. 2008;27:195–200.

52. Westphal GA, et al. Reduced mortality after the implementation of a protocol for the early detection of severe sepsis. J Crit Care. 2011;26:76–81.

53. Dellinger RP, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: intervention guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock 2008. Intensive Care Med.2008;34:17–60.

54. VonRueden K, et al. Shock and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. McQuillan K, et al. Trauma nursing from resuscitation through rehabilitation, ed 4, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009.

55. Griesdale DE, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and mortality among critically ill patients: a meta-analysis including NICE-Sugar study data. CMAJ.2009;180:821–827.

56. Rauen C, et al. Evidence-based practice habits: Transforming research into bedside care. Crit Care Nurse.2009;29:46–59.

57. Lee CS. The role of exogenous arginine vasopressin in the management of catecholamine-refractory septic shock. Crit Care Nurse. 2006;26:17–29.

58. Iacono M. Critical stress debriefing: application for perianesthesia nurses. J Perianesth Nurs.2002;17:423–426.