41 Care of the genitourinary surgical patient

Adrenalectomy: Partial or total excision of one or both adrenal glands.

Bladder Neck Operation (Y-V Plasty): A plastic repair of the bladder neck for correction of stricture.

Chordee: Downward bowing of the penis as a result of congenital malformation or hypospadias with fibrous bands.

Circumcision: Excision of the foreskin (prepuce) of the glans penis.

Cystectomy: Excision of the bladder and adjacent structures; may be partial (excision of a lesion) or total (excision of a malignant tumor). This operation usually involves the additional procedure of ureterostomy.

Cystolithotomy: Opening of the bladder for removal of stones.

Cystoscopy: Direct visualization of the urethra, prostatic urethra, and bladder by means of a tubular lighted telescopic lens.

Cystotomy: An incision into the bladder.

Epididymectomy: Excision of the epididymis from the testis. This procedure is rarely done but may occasionally be indicated for treatment of persistent infection.

Epispadias: Urethral meatus situated in an abnormal position on the upper side of the penis. Surgical correction involves plastic repair.

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy: Use of shock waves through a liquid medium into the body to disintegrate stones.

Heminephrectomy: Partial excision of the kidney.

Hydrocelectomy: Excision of the tunica vaginalis of the testis for removal of a hydrocele (a fluid-filled sac).

Hypospadias: A deformity of the penis and malformation of the urethral wall in which the urinary meatus is located on the underside of the penis, either short of its normal position at the tip of the glans or on the perineum or scrotum. This condition is often associated with chordee. Surgical correction involves plastic repair; penile straightening and urethral reconstruction (urethroplasty) are usually done in two or more stages.

Intravenous Pyelogram: A radiologic procedure in which intravenous dye is injected to assist in the visualization of renal structure. This procedure is used to diagnose abnormalities and look for blockages.

Kidney Transplant: Removal of a donor kidney with nephrectomy and ureterectomy, followed by transplantation of the donor kidney into the recipient’s iliac fossa.

Nephrectomy: Removal of a kidney; used in treatment of some congenital unilateral abnormalities that cause renal obstruction or hydronephrosis; sometimes necessitated by the presence of tumors or severe injuries.

Nephrostomy: An opening into the kidney for temporary or permanent drainage.

Nephrotomy: An incision into the kidney.

Nephroureterectomy: Removal of a kidney and the entire ureter that drains it.

Orchiectomy: Removal of the testis or testes. This procedure renders the patient sterile.

Orchiopexy: Suspension of the testis within the scrotum. This procedure is used in the treatment of an undescended or cryptorchid testis to bring it into the normal intrascrotal position.

Penile Implant: A penile prosthesis implanted for treatment of organic sexual impotence.

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy: Removal or disintegration of renal stones with passage of a nephroscope through a percutaneous nephrostomy tract.

Phimosis: Tightness of the foreskin so that it cannot be drawn back from over the glans; also, the analogous condition in the clitoris.

Prostatectomy: Enucleation of prostatic adenomas or hypertrophied masses.

Pyeloplasty: Revision or reconstruction of the renal pelvis.

Pyelostomy: An incision into the renal pelvis for drainage or for irrigation of the renal pelvis.

Pyelotomy: Incision into the renal pelvis.

Radical Prostatectomy: Common surgical treatment for prostate cancer in young men where the entire prostate is removed.

Spermatocelectomy: The removal of a spermatocele, which usually appears as a cystic mass within the scrotum, attached to the upper pole of the epididymis. A spermatocele is usually caused by an obstruction of the tubular system that conveys the sperm.

Transurethral Surgery: Piecemeal resection of the prostate gland and of tumors of the bladder and bladder neck and fulguration of bleeding vessels and of tumors with a resectoscope passed into the bladder via the urethra.

Urethral sling: Midurethral sling used as treatment for stress incontinence. A piece of mesh is introduced along the midurethral section using an introducer through either a retropubic approach or a vaginal approach.

Ureterectomy: Complete removal of one or both of the ureters.

Ureterolithotomy: Incision into the ureter and removal of stones.

Ureteroneocystostomy (Ureterovesical Anastomosis; Vesicopsoas Hitch Procedure): Division of the ureter from the urinary bladder and reimplantation of the ureter into the bladder at another site.

Ureteroplasty: Reconstruction of the ureter.

Ureteroscopy: Direct visualization of the ureters and upper urinary tract with the use of a lighted semirigid scope that passes through the urethra and bladder.

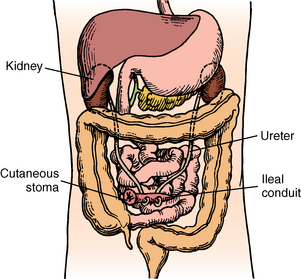

Ureterostomy, Cutaneous (Anastomosis of Transplant; Bricker Operation; Ureteroileostomy): Diversion of the urinary stream with anastomosis of the ureters into an isolated loop of ileum that is brought out through the abdominal wall as an ileostomy.

Urethral Dilatation and Internal Urethrotomy: Gradual dilation of the urethra and lysis of a urethral stricture.

Urethral Meatotomy: Incisional enlargement of the external urethral meatus for relief of stenosis or stricture.

Urethroplasty: Reconstructive surgery of the urethra.

Urethrovesical Suspension (Pubovaginal Slings): Suspension of the urethra with a permanent polypropylene mesh tape for the treatment of stress incontinence.

Varicocelectomy: Ligation and partial excision of dilated veins in the scrotum.

Vasectomy: Excision of a section of the vas deferens. This procedure is performed electively for birth control or before prostatectomy to prevent the spread of infection from the urethra to the epididymis.

Vasoepididymostomy: Anastomosis of the vas deferens to the epididymis.

Vasovasostomy: Anastomosis of two separate segments of the vas deferens for reversal of a vasectomy.

Vesicourethral Suspension: Suspension of the bladder neck to the posterior surface of the pubis in women for treatment of stress incontinence.

Nursing care after diagnostic procedures

Renal angiography

For a renal angiographic examination, a small catheter is threaded through the femoral artery into the aorta or renal artery, radiopaque dye is instilled, and radiographs are made.1 Local anesthesia is usually all that is needed; however, general anesthesia may be used for children or patients who cannot cooperate during the procedure. When the patient is admitted to the PACU, the groin area is inspected for bleeding at the site. A pressure-type dressing usually is present and can be replaced with a simple bandage after a few hours. Pedal pulses should be checked to ensure that no interruption of blood supply to the extremities has occurred. Urine output should be measured and closely monitored for hematuria. Special attention should be considered for the patient with renal insufficiency or renal failure. If possible, the leg should be kept straight. Fluids should be encouraged to facilitate excretion of the dye.2

Renal biopsy

Renal biopsy is usually performed at the bedside with only local anesthesia, although general anesthesia may be used for children. The patient should maintain bed rest in a flat supine position for as long as 4 hours. Some physicians ask for the patients with a previous transplant to maintain a side lying or prone position. Pillows can be used for positioning for comfort and to decrease the risk of skin breakdown. Vital signs are monitored, and the site of the biopsy is checked for bleeding. Coughing and other activities that increase abdominal venous pressure should be avoided. Fluids should be increased to 3000 mL daily, and the urine should be observed for occult blood.3

Cystoscopy

Diagnostic cystoscopy can be performed in a special procedures room with only local anesthesia and appropriate sedation.1 Children and patients who cannot or do not tolerate the procedure may need general anesthesia. This procedure can also be performed with spinal anesthesia.

On admission to the PACU, the patient is positioned to ensure airway patency if general anesthesia was used.4 The patient may have to lie flat on the back if spinal anesthesia was used, with a gradual increase in the head of bed if tolerated and allowed by physician orders. After the effects of anesthesia have been eliminated, the patient may assume a position of comfort. The patient may have back pain, a feeling of bladder fullness, and bladder spasms. These symptoms may become severe enough to necessitate analgesia. Belladonna and opium suppositories or intravenous opioids may be administered to relieve patient discomfort as prescribed by the surgeon.2,3

Oral fluid administration should be encouraged and started as soon as the effects of anesthesia are gone. Urine output should be monitored carefully. The patient can expect frequency of urination and a burning sensation because of trauma to the mucous membranes from the procedure; this condition may inadvertently cause voluntary retention.2,3 The urine may be pink tinged for several voidings, which is to be expected. Bright blood or clots in the urine, however, should be reported to the surgeon. Severe abdominal pain should be reported because it can indicate accidental urethral or bladder perforation or internal hemorrhage.5

General postoperative care

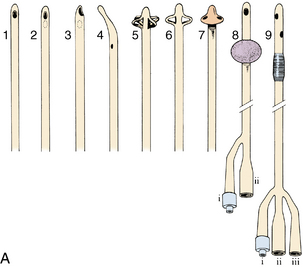

Assessment of the patient after genitourinary surgery involves particular attention to fluid and electrolyte balance. Intake and output records are especially important and must be accurately maintained. Postoperative care is directed primarily at urinary tract function, which is second in importance only to cardiorespiratory function. Maintenance of patency of the urinary tract often depends on the use of catheters, which come in a variety of shapes and sizes (Fig. 41-1).

The catheter should be anchored securely to the patient’s thigh with a leg strap and locking device with the tubing brought over the leg. The catheter should be secured to prevent undue tension on the urinary meatus. The connecting tubing should be attached to the bed linens so that no proximal loops of tubing lie below the distal tubing; this is a straight gravity drainage system. The tubing should never be under the patient, because compression of the tubing obstructs the flow of urine. The tubing should be checked frequently for kinks. The urine receptacle should always be kept below the bladder level to prevent urine reflux up the tubing. Particular attention must be paid to this principle during the transfer of patients.

Mucus or blood, or both, can clog the tubing and prevent urine flow. Irrigations should be administered only according to the surgeon’s orders. All irrigations are sterile procedures and can be either continuous or intermittent. For intermittent irrigation, a large sterile Toomey syringe and sterile irrigating solution (usually normal saline solution alone or with a selected antibiotic) are used. Care must be taken to keep all parts of the drainage system sterile. This action may be accomplished by placing a small sterile plastic cover on the drainage tubing while the irrigation is performed. Irrigations should never be given with pressure. When the bladder is irrigated, no more than 30 mL should be instilled at one time, unless ordered otherwise by the surgeon.1

After transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), continuous irrigation is usually preferred. With continuous irrigation, normal saline solution is typically connected with a three-way urinary catheter. Nursing care should include vigilant monitoring of patients for hyponatremia and the development of TURP syndrome.6 The report from the perioperative nurse should include the amount of intraoperative irrigation and the duration of the procedure. During the immediate postanesthesia phase, patient confusion should be monitored and differentiated from confusion as a result of amnesiacs, opioids, or hyponatremia (see also the Prostatic Surgery section in this chapter).

If hyponatremia is diagnosed, treatment may include the administration of hypertonic saline solution for a gradual increase in the patient’s serum sodium level. Care includes monitoring for signs of intracellular to extracellular fluid shifts. As fluid moves back into the extracellular space, pulmonary edema and heart failure can occur quickly.6

Suprapubic catheters

A suprapubic catheter can also be placed into the urinary bladder via abdominal incision and cystostomy.1 This procedure is typically done for more permanent or long-term use of the suprapubic catheter. The surgeon may choose this method if conventional methods of treatment for urinary incontinence fail, as with spinal cord injury or neurogenic bladder. The care of the catheter is the same as with the puncture wound, but the nurse should also apply nursing care that relates to the abdominal incision.

Ureteral catheters

Ureteral catheters are used to drain urine or splint the ureters while they heal. The catheters can be placed through the urethra or through abdominal or flank incisions.1 Care of these catheters is essentially the same as that for urethral catheters. Attention to patency must be especially meticulous because the renal pelvis can hold only 5 mL without overdistention and damage to the kidneys.1,2

Sterile irrigations are undertaken only as ordered by the physician. Only 5 mL of fluid should be used for the irrigation via gravitational flow. Irrigations should never be given with pressure, such as with a syringe and plunger. The nurse must be sure to avoid situations that can cause dislodgement or displacement of these catheters, which could be disastrous to the outcome of the surgery. Special care must be taken during patient transfer to ensure that these catheters stay in place. One person should be assigned this responsibility during the transfer. If the catheters should become dislodged despite all the precautions taken, the surgeon must be notified immediately.1,5

Intake

Optimal fluid intake is exceptionally important for the patient after surgery; increased fluids are the general rule. Fluids should be given orally if the patient can tolerate this preferred route, and intake should be increased to total of 3000 mL in a 24-hour period. Special consideration regarding type and amount of fluids should be taken with any patient with renal insufficiency. Parenteral fluid therapy is indicated for a short time until the effects of anesthesia have passed and is continued only if the oral route of intake is inadequate.2,4

Dressings

Care of dressings varies according to the procedure and can include anything from a bulky dressing to Steri-Strips or bandages. Dressings applied after urinary tract surgery often become soaked with blood and urine. They should be reinforced as necessary, and the surrounding skin should be kept clean and dry to prevent unnecessary excoriation and breakdown.3 (Excessive staining that is unexpected for a particular procedure and indicates a complication is so indicated in the discussion of the specific procedure later in this chapter.) Excessive bleeding and hemorrhage are ever-present dangers of this surgery, because the kidneys and prostatic bed are extremely vascular. Vital signs must be monitored closely, and all avenues of output, especially the incisions and drainage tubes, should be evaluated frequently for bleeding.2,3

Abdominal distention

All patients should be assessed for abdominal distention after surgery that involves abdominal and flank incisions (see Chapter 40 for care of the patient after an abdominal incision because the same care applies after genitourinary surgery). These patients often arrive with nasogastric tubes, the care for which is discussed in Chapter 40. In addition, the patient should be assessed for distention caused by overfilling of the bladder because of an inability to void or a malfunction of the catheters.

Bladder ultrasound scan is a noninvasive method to assess bladder volume for determining bladder distention or postvoid residual urine. This portable battery-operated device can be used at the bedside as a noninvasive replacement to intermittent catheterization (Fig. 41-2). This painless procedure eliminates discomfort, embarrassment, and risks associated with catheterization. Data from the bladder ultrasound scan can be printed and become part of the patient’s chart. Depending on the volume and whether the patient is capable of voiding, straight catheterization should be performed to relieve urinary retention; this procedure is typically done with volumes greater that 300 mL. A bladder ultrasound scan can be repeated as necessary and has been shown to decrease the risk of urinary tract infections associated with intermittent catheterization.7

FIG. 41-2 Using a bladder scanner to determine amount of urine in the bladder.

(From deWit S: Fundamental concepts and skills for nursing, ed 3, St. Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

Management of discomfort and pain

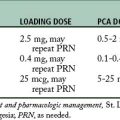

Discomfort after genitourinary surgery can be relieved with the administration of opioids, including intravenous morphine or fentanyl, belladonna, and opium suppositories. In the outpatient setting, the nurse may consider using oral medications such as oxycodone and hydrocodone. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should also be considered.8 The physiology of the need to void should be explained to the patient before surgery. The patient should be instructed not to attempt to void around the catheter, because exertion of pressure causes the bladder muscles to contract and results in painful bladder spasms. The avoidance of straining around the catheter and of intake of excessive fluids decreases bladder irritability and spasms. As the nerve endings become fatigued, the frequency and severity of the spasms diminish.

Nursing care after specific procedures

Renal and ureteral surgery

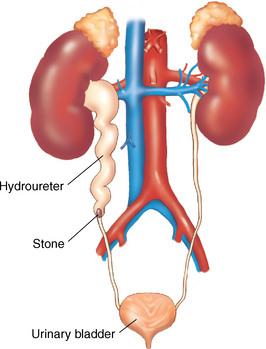

General anesthesia is commonly used for surgery on the kidneys and ureters. The kidneys are usually approached posteriorly through an incision that requires resection of the 11th or 12th rib. The surgical approach to the ureters is made through muscle-splitting flank incisions (Fig. 41-3).1,5 The perianesthesia course for these patients is usually smooth and involves general care and maintenance of urinary tract function. The patient should be placed in a position that avoids tension on suture lines or as indicated by the surgeon.

FIG. 41-3 Hydroureter is caused by obstruction in the lower part of the ureter.

(From Leonard PC: Building a medical vocabulary, ed 8, St. Louis, 2012, Saunders.)

All surgical patients are at risk for fluid volume deficit from the intake restrictions before surgery and from the decreased intake after surgery, possibly related to postoperative nausea or vomiting.2,3 Maintenance of exceptionally accurate intake and output records is important. Low urine output should be reported to the surgeon.

Skin care for these patients is important. Urine should not be allowed to remain on the skin. Plain water should be used to cleanse the skin, which should be carefully dried. No powders, lotions, or harsh skin preparations should be applied to the skin. If a ureteroileostomy has been performed, the stoma must be inspected frequently to ensure adequate vascularization. If skin turns a bluish hue, the surgeon should be notified immediately.2

A urinary catheter is often in place and receives care as previously discussed. Fluid intake is increased both orally and parenterally to keep blood clots from forming in the ureters or bladder. Intestinal decompression may be necessary and is accomplished via nasogastric tube (see Chapter 40). Decompression is essential when an ileal conduit procedure (ureterostomy) is performed to allow healing of the intestinal anastomosis (Fig. 41-4).3,5 Any evidence of abdominal distention should be reported to the surgeon immediately.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy

After extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, the patient may be admitted to the PACU for a brief period of observation.5 Vital signs should be monitored as with any renal or ureteral surgery. Fluids should be increased, and intake and output monitored carefully. Initially, the color of the urine may be cherry red to pink because of trauma from surgery; this condition may take several hours to clear. Petechiae, redness, and bruising may be seen on the skin at the site of lithotripsy. This petechiae should be documented by the perianesthesia nurse on assessment in the PACU. The patient may have pain from the force of the shock waves. This pain is usually localized to the skin and may be relieved with ice packs. Renal colic pain may also be experienced as the fragments of pulverized stones pass through the lower urinary tract.2

Ureteroscopy

Since the 1980s, rigid ureteroscopy has been used for the removal of distal ureteral calculi.1 Today, flexible and rigid ureteroscopy are used for the diagnosis and treatment of stones, fulguration of epithelial tumors, analysis of gross hematuria, and management of ureteral strictures.1 Complications are rare but include perforation of the ureter; therefore close observation of color and amount of urine output should be maintained. All urine should be strained, and any calculous fragments should be collected for inspection and identification. Ureteral stents are commonly placed during this procedure to facilitate urine flow and prevent obstruction or ureteral colic caused by edema.1 If the surgeon has elected to externalize the stent suture, patients should be educated on its care.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy

Large stones that are not easily removed with ureteroscopy can be removed through a percutaneous tract into the renal collecting system. Local anesthesia or moderate sedation is used to establish the percutaneous nephrostomy tract with the guidance of fluoroscopy or ultrasound scan. A plastic sheath is left in place through which a rigid or flexible nephroscope can pass. Stones smaller than 1 cm can be removed manually with a grasping forceps. General anesthesia is used for the surgical procedure itself. For stones greater than 71 cm, lithotripsy is used according to the surgeon’s preferred method and the location of the stone.1

Postoperative nursing care should include the consideration of surgical complications and all postanesthesia considerations.2,3 Blood loss from damage to an intrarenal artery is the most significant complication of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Extravasation of the irrigation solution used during surgery is another complication. Rare complications include damage to the surrounding organs caused by perforation with the placement of the percutaneous nephrostomy tube. The nephrostomy tube may be left in place for 1 to 5 days. Pain at the nephrostomy site may require management with opioids. As with all genitourinary surgeries, adequate fluid intake is encouraged.2,3

With each of the types of renal stone removal procedures, nursing care should include patient education on types of stones, diet for the prevention of stones, and fluid intake to improve the excretion of stones and prevention of new stone formation.9 There are five types of renal stones: calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, uric acid, struvite, and cysteine.10,11 Of these the calcium oxalate stone is the most common. Each stone has different diet and fluid intake recommendations and restrictions. It is important to educate patients on the importance of follow-up with the surgeon in order to identify the type of renal stones they are producing. By knowing the chemical makeup of the stone, the surgeon is able to make specific recommendations to the patient (Box 41-1).

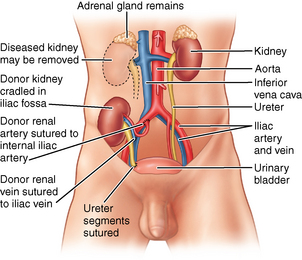

Kidney transplantation

The kidney is the most commonly transplanted organ and the only one that can be preserved in a viable state for some time (Fig. 41-5). The kidney is relatively easy to remove and implant. Most people have two functioning kidneys and need only one to sustain life; therefore kidney transplantation is done only for patients who need the organ to replace a diseased or nonfunctioning solitary kidney. Transplantation can be accomplished two, three, or more times in the same patient, with the use of hemodialysis when a functioning kidney is not in place.12

FIG. 41-5 Transplanted kidney in place.

(From Black JM, Hokanson Hawks J: Medical-surgical nursing: clinical management for positive outcomes, ed 8, St. Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

Kidney grafts come from two sources: cadaver donors and living donors. Most living donors are a close blood relative of the recipient. Ideally, an identical twin is the best donor. The closer the recipient and donor in blood line, the better the chances for survival of the kidney graft. Although the living related donor is best, cadaver donors are the most common source for kidney graft.1,5,12

General anesthesia is the preferred method of anesthesia for both the donor and the recipient in renal transplantation.4 After surgery, care of the living donor is essentially the same as that for the patient who has undergone nephrectomy.12 All care considered previously for the urologic patient applies, as does care for the patient after abdominal incision. If the laparoscopic approach was used for the living donor, four to five stab wounds are found from the trocars used during surgery.1,12 Postoperative priorities include accurate intake and output, fluid volume and electrolyte replacement, adequate pulmonary perfusion, and pain and comfort measures.

Because postoperative care is routine, the donor patient often feels forgotten. Before surgery, the patient was considered heroic and received a generous helping of attention and glory. After surgery, attention is directed primarily to the organ recipient. The donor patient feels this even in the PACU. For this reason, the perianesthesia nurse must be aware of the needs of the postoperative donor and show concern for the patient’s physical and psychologic well being. The care of these patients should be assigned to separate teams, if possible. In addition to normal self concern, the donor is concerned about the recipient and should receive factual information.12

For the renal transplant patient, the commonly used immunosuppressive agents are nonspecific and suppress the entire immune system. However, immunosuppressive therapy is vital to the treatment for the renal transplant patient to prevent rejection of the donor kidney. Calcineurin inhibitors, which block production of interluekin-2 in the T cell lymphocyte, purine inhibitors, and steroids are the first-line medications given for immunosuppression. A transplant patient receives one drug from each category. Sometimes, an antibody agent directed against T cells is given (Box 41-2).8,12 PACU nurses should know the specific agents and transplant protocols used by their hospitals. Wound infections are among the common causes of death after kidney transplantation.12 Meticulous aseptic technique is therefore imperative with these patients to prevent the introduction of infection.

BOX 41-2 Immunosuppression Medications

• Induction (administered in the first week after transplantation)

• Maintenance (administered during the first week and maintained throughout viability of transplant)

• Rejection (administered when rejection is identified, often the first 2 to 4 weeks after transplant)

From Barone CP, et al: The postanesthesia care of an adult renal transplant recipient, J Perianesth Nurs 18:32-41, 2003.

On admission to the PACU, the recipient should be kept in a flat position for 12 hours, which allows the kidney to set. The head of the bed may be elevated 30 degrees to provide comfort and respiratory care. After 12 hours, the patient may turn to the side of the transplant. Turning to the opposite side may dislodge the graft. All vital signs are monitored continuously. Many renal transplant patients need antihypertensive medications after surgery. Blood pressures are more easily controlled as the fluid status becomes stable.12

A urinary catheter is in place, and all urine should be carefully monitored for volume and specific gravity. During the immediate postoperative period, the renal allograft is extremely sensitive to hypovolemia, and even a transient period of poor renal perfusion can result in oliguric renal failure. The kidney from a living donor may start to function almost immediately after transplantation, and diuresis occurs. The volume of urine output may be great enough to warrant measurement every 15 minutes. The cadaver kidney, however, reacts more slowly, depending on the cold ischemic time spent during transportation.12

Urine samples are generally collected hourly to ascertain electrolyte content, creatinine level, and osmolarity. Once daily, the total 24-hour urine collection (minus the small samples sent hourly) is sent to the laboratory for creatinine clearance test and culture. Urine output less than 1 mL/kg/h should be reported to the surgeon, because any decrease in urine output may be a sign of early rejection or complications of the anastomosis site.12 Likewise, any gross hematuria should be reported immediately. A baseline postoperative weight should be ascertained as soon as feasible.

Other nursing considerations include care of the potential nasogastric tube that provides intestinal decompression and receives care as discussed previously. A central venous pressure line may be present for assessment of the patient’s cardiovascular status. Monitoring of these systems is imperative to ensure adequate renal perfusion and prevent fluid overload. Skin integrity should be maintained, and the dressing over the incision site should exhibit a minimal amount of drainage. The recipient may have a stenting catheter from the renal pelvis out through the urethra along with the urinary catheter for the first 36 to 48 hours to ensure ureteral patency.2,3

Intravenous fluids provide most of the intake for these patients until the nasogastric tube can be removed. Intravenous replacement fluid composition is determined by the serum and urine electrolyte content, the hematocrit, and the clinical course of the patient. Volume is determined from necessary fluid requirements of the patient in normal status plus replacement on a volume-to-volume basis of drainage from the urinary catheter, nasogastric tube, ureterostomy, and cystostomy.1,12 For the first 72 hours after operation, the major source of output is from the ureterostomy.1 Meticulous handling of the closed urinary drainage system is mandatory to prevent the introduction of infection.

The threat of graft rejection is always present; therefore the health care professional must observe closely for signs of rejection.2,12 Hyperacute allograft rejection can occur within minutes of the completion of the vascular anastomosis or in the first few postoperative hours.1,12 Signs and symptoms of hyperacute rejection are noted in Box 41-3. To prevent irreversible damage to the kidney, treatment of a threatened rejection immediately is of the utmost importance.

Bladder surgery

The bladder is a smooth muscle storage tank that holds urine until a reflex, normally with voluntary control, releases the urine to pass through the urethra to be eliminated.1 Surgical procedures on the bladder include the removal of stones, foreign bodies, and tumors; the repair of strictures at the bladder neck and of injuries, such as lacerations; and the removal of the bladder itself.1,5

Anesthesia for these procedures may be either spinal or general.1,4 On admission to the PACU, the patient is placed in a supine position. The head of the bed can be raised 30 degrees as soon as feasible. The removal of stones or foreign bodies and the resection of selected tumors can be accomplished via cystoscopy, which was discussed previously. After the repair of lacerations or after cystotomy for removal of stones, the patient is admitted to the PACU with a urinary catheter and a urinary diversion, such as a suprapubic cystostomy, usually in place. Urine from these drainage systems is pink tinged but should not become grossly bloody. Dressings should remain dry and intact, fluids should be increased, and oral fluids should be started as soon as the effects of anesthesia have passed.

Cystectomy

Lacerations or ruptures of the bladder are often the result of accidental trauma. They require emergency surgery, and the postoperative patient should be assessed carefully for any unrecognized associated injuries.1 Pain should be minimal to moderate for these patients and easily controlled with analgesics. The presence of severe pain may represent a complication, such as internal hemorrhage and damage to a ureter, and should be reported to the surgeon.

Cystectomy may be performed as a result of trauma or underlying pathology, such as muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Whether the cystectomy is partial or radical (including hysterectomy and anterior vaginectomy in females and prostatectomy in males), urinary diversion is necessary.1,5 Care for an ileal conduit was discussed in the section on ureteral surgery. Other forms of urinary diversion include Koch pouch, cutaneous continent ileocecal reservoir, and ileocolic neobladder and orthotopic bladder substitution. The type of urinary diversion is specific for each patient with consideration to age, height and weight, surgical history, and medical history.13,14

Postanesthesia care includes all the principles of surgical nursing along with special consideration to drains and catheters specific to type of diversion. The PACU nurse should observe the patient for potential complications that include stricture of the anastomosis site, rupture of the reservoir with neobladder or Koch pouch, infection, and any metabolic complications. Irrigation of the urethral catheter with 50 mL of saline solution 0.9% every 6 hours while the suprapubic catheter is freely draining is started immediately after surgery to prevent mucous from clotting the catheter.13,14

Bladder neck suspensions

Quality of life challenges are significant in patients with incontinence. Bladder neck suspensions in a variety of techniques are performed to correct urinary stress incontinence.1,5 Postoperative complications for all techniques include urinary retention, wound infection, urinary tract infection, continued incontinence, retroperitoneal hemorrhage, and organ perforation.2

Sling procedures including the Tension-Free Vaginal Tape (TVT Sling) are a recent development for the correction of urinary stress incontinence caused by pelvic floor relaxation in women and are considered a first-line surgical intervention. This procedure can be done with local anesthetic and MAC. Potential complications include postoperative voiding difficulties, bowel perforation, and erosion of the tape into the bladder, urethra, or vagina.15

Artificial urinary sphincter

Another treatment for urinary incontinence is the placement of an artificial urinary sphincter (AUS). This invasive procedure is a method to restore control over urinary function. AUS is a prosthetic device that consists of three parts: a balloon pressure reservoir, a control pump that is implanted in the scrotum or labia, and a cuff that occludes the urethra. This prosthetic device substitutes for the sphincteric mechanism and prevents the loss of urine. Indications for this procedure include postprostatectomy urinary leakage, congenital disorders of the bladder, and unsuccessful reconstructive surgery of the urethra.13,14

Postanesthesia care includes principles of care for patients receiving general anesthesia. Specific assessment for this procedure includes observation for signs of hematoma along the plane of dissection for the pump in the scrotum or labia.13 A bladder ultrasound scan can be used to assess for urinary retention that can result from edema around the cuff site.1

Along with the use of opioid analgesics to control pain, ice packs to the scrotum or labia and perineal areas provide comfort and prevent swelling. The patients arrive in the PACU with an indwelling catheter, and traction on the urethral catheter should be prevented to avoid increased pressure on the cuff of the sphincter.13

Prostatic surgery

The prostate gland is a small, walnut-sized male reproductive organ. Its sole function is to manufacture a secretion that becomes part of the semen; the prostate gland is a nonessential organ. Surgical procedures performed on the prostate gland include the excision of tumors and the resection or total removal of the gland.1

The preferred anesthesia is spinal, although general anesthesia may be used. Several different approaches are common in surgery on the prostate.6 The transurethral approach is the most common, especially if only minor obstructive lesions or small portions of the gland are to be removed. A resectoscope is introduced through the urethra, and the surgeon excises the tissue with a moveable tungsten wire that operates on high-frequency current controlled with a foot pedal.1,5

When the patient is admitted to the PACU after TURP, a three-way urinary catheter may be in place (see Fig. 41-1, A). One lumen allows filling of the retention balloon, one lumen allows outflow of the urine and irrigation fluid from the bladder, and one lumen is attached to the irrigation fluid system. Irrigation fluid, which is usually normal saline solution at room temperature, is available in 3000-mL plastic bags and may be regulated like intravenous solutions. To avoid creation of a hypothermic state with irrigation of the bladder with this solution, the saline solution should be warmed before administration, and the patient’s body temperature should be monitored.2 The triple-lumen catheter is advantageous in that blood clots do not regularly form and block the system when the flow is continuous. The irrigation rate should be regulated so that drainage remains a light-pink watermelon color. If drainage becomes bright red, speed up the irrigation; if the returning fluid is clear, slow down the irrigation. Some institutions use a Y-connecting system with one arm of the Y connected to the irrigating fluid and the other to straight-gravitational drainage from the bladder. In either instance, a fair amount of bleeding can be expected after TURP, because the prostatic bed is highly vascular. This bleeding may also increase as the spinal anesthesia wears off and may require frequent irrigation to prevent clogging of the drainage tube. If the catheter becomes clogged, the surgeon should be notified and may order irrigation with a piston syringe and the same normal saline irrigating solution. If patency of the catheter cannot be reestablished, the surgeon must be notified.2,3

The patient’s vital signs should be monitored closely. Observe for signs and symptoms of post-TURP syndrome (hyponatremia) that can occur from venous absorption of the irrigation fluid through the venous sinuses. Serum sodium and potassium levels should be checked during the postoperative period, because changes in fluid balance may affect these electrolytes. Signs and symptoms of hyponatremia are a low serum sodium level, tachypnea, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, hypertension, bradycardia, increased pulse pressure, restlessness, apprehension, and mental disorientation.6 If this syndrome occurs, the perianesthesia nurse should notify the anesthesia provider and surgeon, administer oxygen to the patient, monitor blood loss and electrocardiographic and fluid and electrolyte status, and administer intravenous fluid (hypertonic saline solution 3% or 5% in 100 mL/h increments until the serum sodium level is satisfactory) and diuretics to mobilize the edema.2,6

Pain should be minimal to mild and easily controlled with analgesics. Analgesics or tranquilizers can be administered to control the discomfort of bladder spasms and of the presence of the catheter, which makes the patient feel an urgency to void although the bladder is being emptied. Symptoms of abdominal pain, abdominal rigidity, increased pulse rate, and other signs of shock should alert the nurse to the possibility that the bladder wall or the capsule of the prostate was accidentally perforated during surgery; these symptoms should be reported to the surgeon immediately.3,8

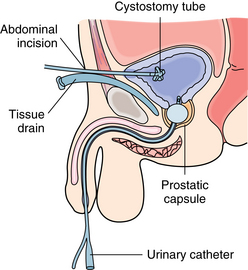

Other approaches to prostatic surgery include retrograde or suprapubic, perineal, and retropubic incisions.1,5 When the suprapubic approach is used, a midline vertical incision is made in the lowest part of the abdomen, the bladder is incised, and the tumors are removed.1 This procedure is the choice when 60 g or more of tissue is to be removed. The patient is admitted to the PACU with a urinary catheter, which may or may not be attached to an irrigation system. If it is not connected to an irrigation system, the catheter has to be irrigated frequently via syringe to prevent clots from clogging the drainage system.2,5 The patient also has a suprapubic catheter that should be connected to straight-gravitational drainage in place; output should be measured carefully (Fig. 41-6). In addition, a small Penrose drain is inserted in the suprapubic space and brought out through a separate stab wound. A dressing of several layers of 4 × 4 sponges should cover the incision and the drain. A moderate amount of serosanguineous drainage can be expected because of the presence of the drain. This dressing should be reinforced as necessary to keep the skin clean and dry. If excessive bright-red bleeding occurs, the surgeon must be notified.

FIG. 41-6 Suprapubic prostatectomy. Note placement of inflated urinary catheter in prostatic fossa.

(From Monahan FD, et al: Phipps’ medical surgical nursing: health and illness perspectives, ed 8, St. Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

The surgeon can apply traction to the urinary catheter by taping the catheter to the inner thigh. Because the traction puts tension against the vesical outlet and promotes hemostasis, it can produce painful bladder spasms that may be relieved with the use of intravenous opioids or belladonna and opium suppositories as prescribed by the surgeon.1,5 After the traction is removed, a small increase in bleeding can be expected for a short time.

The perineal approach, used for removal of large amounts of tissue, is the approach of choice for prostatic cancer.1,5 A V-shaped incision is made above the rectum in this approach. The patient is admitted to the PACU with a urinary catheter and a perineal drain. Because of the perineal drain, a moderate amount of serosanguineous drainage can be expected, and the dressing should be reinforced as necessary. No instrumentation, including thermometers, should be placed in the rectum during the immediate postoperative period.

When a retropubic approach is used, a small incision is made above the pubis and a capsular incision is made into the upper surface of the prostate.1 This approach is used in the nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy for patients whose carcinoma is confined within the prostate.1 This approach is preferred because of the decreased risk of postoperative complications of long-term incontinence and impotence.

On the patient’s arrival to the PACU, a urinary catheter is in place and a small drain may be present that was inserted in the incision or brought out through a stab wound lateral to the incision. As with all urologic patients, accurate intake and output records must be maintained after prostatic surgery. The perianesthesia nurse must be sure to indicate in the output data whether irrigation solution is included. Output should be documented hourly. Color and appearance of urine should be monitored closely and documented.

Most prostatic surgery is performed on adult men older than 50 years of age because prostatic hypertrophy most commonly occurs after 40 years of age.10 As a result, assessment of cardiorespiratory status should be performed frequently. Oxygen should be administered and weaned with pulse oximetry. All patients should be connected to a cardiac monitor for assessment of changes. Astute observation of vital signs is imperative to monitor cardiovascular function, because postoperative bleeding may impair it. Observe carefully for decreasing blood pressure and increasing pulse rate, which may indicate impending shock.2,3

One of the most common postoperative complications after the nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy is pulmonary embolism. For this reason, the surgeon may order low-dose heparin. Care in the PACU should include deep-breathing exercises and position changes along with passive or active movement of the extremities.2 As with other urologic procedures, some type of antiembolism stocking or sequential compression device should be used.2,3

Scrotal surgery

The scrotum is a sac separated into two pouches: externally by the median raphe and internally by the dartos tunic. Each pouch contains a testis, an epididymis, and a spermatic cord. The vas deferens, which is continuous with the epididymis at the lower end of the testis, and the arteries, veins, nerves, and lymphatic vessels that are held together by spermatic fascia form the spermatic cord.1 Operations on the scrotum include excision of masses and tumors, correction of deformities, and excision of diseased or abnormal structures that interfere with normal function.1,5

Anesthesia for scrotal surgery may be local, general, or spinal. Spinal anesthesia is commonly used for adult patients, whereas general anesthesia is usually preferred for children younger than 12 years. Local anesthesia is often used for simple procedures, such as vasectomy and epididymectomy.1,4

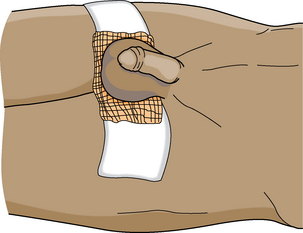

The PACU course after surgery on the scrotal structures is usually uneventful. Care is dictated primarily by anesthesia agent and its method of administration.4 The patient may assume a position of comfort after surgery. Any dressings present should remain dry and intact. Oral food and fluids may be reinstituted as soon as the patient tolerates them. An athletic supporter commonly is applied to provide scrotal support and elevation (Fig. 41-7). This device is suspended from thigh to thigh, with a tight sling across the expanse on which the scrotum is supported. A T-binder may also be used (Fig. 41-8).2

FIG. 41-7 A simple scrotal support.

(From Monahan FD, et al: Phipps’ medical surgical nursing: health and illness perspectives, ed 8, St. Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

FIG. 41-8 T-binder for scrotal support.

(From Harkreader H, et al: Fundamentals of nursing: caring and clinical judgment, ed 3, St. Louis, 2007, Saunders.)

As with any genital surgery, the patient’s body image concerns and questions of fertility in particular may be of paramount importance. These concerns are not usually addressed in the PACU, but the nurse must be sensitive to them and be prepared to assist the patient with factual information and reassurance. Often these patients feel an urgency to inspect the operative site and should be assisted to do so, if necessary.

Penile and urethral surgery

Surgery on the penis and urethra involves removal of tumors or obstructions to urinary flow, plastic repair of deformities, and circumcision or excision of the foreskin.1 Partial or total amputation of the penis is rarely necessary, but can be performed for malignant disease, which is essentially skin cancer. Laser technique is generally effective for the treatment of condyloma acuminata and squamous cell carcinoma of the penis.

Anesthesia for these procedures may be local, general, or spinal. The PACU course is usually smooth, and care is determined primarily by the type of anesthesia.4 Physical care of the patient who has had a plastic repair of hypospadias or epispadias is dictated by the surgeon. Care after cystoscopy was discussed at the beginning of this chapter; the same care applies for patients who undergo cystoscopy for the resection of tumors.

Patients who have undergone surgery on the penis should avoid erection during the PACU phase and for at least 1 week after surgery. Patients with penile prostheses should be admitted to the PACU with the penis in a flaccid state; the prosthesis should remain deflated. Inflation of the prosthesis should be avoided until after the first postoperative visit to the surgeon.5

Pain may be significant but should not be severe. Scrotal and penile support with a Bellevue bridge and the application of a light ice pack provide some relief; however, analgesia with small doses of opioids may be necessary.2,5 Food and fluids may be restarted as soon as the patient tolerates them. Urine output should be checked and recorded. Low abdominal distention on palpation may be caused by voluntary retention, which is not uncommon because of fear that micturition creates pain. The patient should be reassured and informed that overdistention of the bladder causes an increase in discomfort and possible complications.2

Adrenalectomy

Adrenalectomy involves the removal of one or both of the adrenal glands, which are situated on top of the kidneys.1,5 Adrenalectomy, an extensive and shock-producing procedure, may be performed for several reasons, including metastasized cancer from the reproductive organs, hyperfunction caused by hyperplasia of the organ, and adrenal tumors. The following two adrenal tumors are of major consequence: pheochromocytoma, a usually benign tumor that causes hyperfunction and results in severe symptoms, and neuroblastoma, a malignant tumor that is a leading cause of death in childhood.1,11

General anesthesia is used for adrenalectomy and can include the use of cortisone titrated to maintain catecholamine levels and blood pressure. Cortisone is usually necessary only when bilateral adrenalectomy is performed or when the uninvolved adrenal gland has poor function. The administration of cortisone, which is continued in the PACU, is an extremely important nursing procedure. The anesthesia provider and surgeon should give specific instructions for titration of the solution.4 Failure to maintain postoperative levels of cortisone leads to hypovolemic and hyponatremic shock.1 Perianesthesia care of these patients is a nursing challenge; observations must be especially astute.

The surgical approach for adrenalectomy may be lateral, anterior, or posterior.1,5 On admission to the PACU, the patient is placed in the side-lying position until reactive from anesthesia, at which time the patient is placed in a semi-Fowler position. The surgeon may prefer the patient to be positioned on the operative side so that the perinephric space is obliterated to discourage bleeding. Assessment is aimed primarily at the cardiovascular status of the patient because hemorrhage and shock are the two most common and most disastrous complications. Profound shock may develop because of the reduction of circulating catecholamines that is precipitated by removal of the glands and the effects of the drugs used for preoperative control of hypertension.1,2 The effects of these drugs usually last for a few hours after surgery. Because most of these drugs produce vasodilation, they are usually a factor in postoperative hypotension; therefore a fluid challenge usually is given in an attempt to treat hypotension. If fluid is not successful in increasing the blood pressure, then vasopressor drugs are used. Epinephrine or norepinephrine in an intravenous solution can be titrated to maintain blood pressure, according to the surgeon’s instructions.

Shock can also result from hemorrhage because the adrenal glands are extremely vascular. Intravenous fluids, including hypertonic saline solutions, blood, plasma, dextran, and glucose in water can be used to maintain blood volume and prevent shock.1,2 Dressings over the bilateral incisions should remain relatively dry, although drains are placed. If these dressings become soaked, the surgeon should be notified because this represents excessive bleeding. If the patient has abdominal pain, abdominal distention, nausea, or vomiting, development of an abdominal hematoma may be indicated; these signs should be reported to the surgeon.2

Other parameters of the patient’s status that can give clues to the development of shock should also be assessed. Dehydration (increased urine specific gravity) and restlessness may indicate developing shock. Central venous pressure should be checked. A urinary catheter should be in place, and urine output should be monitored hourly. The development of oliguria or output of less than 1 mL/kg/h can indicate shock and subsequent renal shutdown.2,3 Serum and urine electrolyte levels, especially sodium, should be determined hourly.

All care outlined for the patient after high abdominal incisions in Chapter 40 is applicable to this patient. Good pulmonary toilet should be instituted immediately in the PACU. A nasogastric tube often is necessary until normal intestinal peristalsis returns. Incisional pain may require the use of opioid analgesics. Because many opioids have a hypotensive effect, they should be titrated judiciously; blood pressure must be monitored continuously for at least 30 minutes after their administration.

Summary

This chapter has discussed the perianesthesia care of the patient who undergoes genitourinary surgery. The perianesthesia nurse should have an understanding of anatomic location and normal function of this system and the important postanesthesia nursing concerns for this type of patient. Adrenalectomy was included in this chapter because of the proximity of the adrenal glands to the kidneys.

1. Tanagho E, McAninch. Smith’s general urology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

2. Schick L, Windle PE. Perianesthesia nursing core curriculum: preprocedure, phase I and phase II PACU nursing. St. Louis: Saunders; 2010.

3. Stannard D, Krenzischek. Perianesthesia nursing care: a bedside guide for safe recovery. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 2012.

4. Stoelting R, Miller R. Basics of anesthesia, ed 6. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2011.

5. Rothrock J. Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 14. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011.

6. Eaton J. Detection of hyponatremia in the PACU. J PeriAnesth Nurs. 2003;18(6):392–397.

7. Krapp K, Gale T. Bladder ultrasound. Encyclopedia of Nursing & Allied Health. eNotes.com 2006, available at http://www.enotes.com/bladder-ultrasound-reference/bladder-ultrasound, 2002. Accessed January 30, 2012

8. Katzung B. Basic and clinical pharmacology, ed 10. Los Altos, CA: McGraw Hill; 2006.

9. National Kidney Foundation: Diet and kidney stone fact sheet. available at www.kidney.org/atoz/content/diet.cfm

10. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse: Kidney stones in adults. available at kidney.niddk.nih.gov/KUDiseases/pubs/stonesadults/index.aspx

11. Litwin M, Saigal C. Uroligic diseases in America. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office: NIH pub No 07-5512; 2007.

12. Barone C, et al. The postanesthesia care of an adult renal transplant recipient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2003;18(1):32–41.

13. Quallich S, Ohl D. Urinary sphincter, part I: overview. Urol Nurs.2003;23(4):259–268.

14. Quallich S, Ohl D. Artificial urinary sphincter, part II: patient teaching and perioperative care. Urol Nurs.2003;23(4):269–273.

15. Polt C. Taking the pressure off for women with stress incontinence. Nursing. 2006;36(2):49–51.

Alspach JG. Core curriculum for critical care nursing, ed 6. St. Louis: Saunders; 2006.

Atlee J. Complications in anesthesia, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Barash PG, et al. Clinical anesthesia, ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Barrett K. Ganong’s review of medical physiology, ed 23. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2010.

Bickley LS, Szilagyi PG. Bates’ guide to physical examination and history taking, ed 9. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Brunton L, et al. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, ed 11. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2005.

Canale ST, Beaty JH. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics, ed 11. St. Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Cottrell J, Smith D. Anesthesia and neurosurgery, ed 4. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001.

Fleisher LA. Anesthesia and uncommon diseases, ed 5. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Hall J. Guyton & Hall’s textbook of medical physiology, ed 12. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

Hamlin L, et al. Perioperative nursing: an introductory text. Chatswood, Australia: Elsevier; 2009.

Hanson K. Minimally invasive and surgical management of urinary stones. Urol Nurs. 2005;25:458–464.

Lake C, et al. Clinical monitoring: practical applications for anesthesia and critical care. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001.

Miller R, et al. Miller’s anesthesia, ed 7. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

Nagelhout J, Plaus K. Nurse anesthesia, ed 4. St. Louis: Saunders; 2009.

Overstreet DL, Sims TW. Care of the patient undergoing radical cystectomy with a robotic approach. Urol Nurs. 2006;26(2):117–125.

Peliciano T, et al. A retrospective, descriptive, exploratory study evaluating incidence of postoperative urinary retention after spinal anesthesia and its effect on PACU discharge. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008;23(6):394–400.

Perimenis P, Koliopanou E. Postoperative management and rehabilitation of patients receiving an ileal orthotopic bladder substitution. Urol Nurs. 2004;24(5):383–386.

Stoelting R, Hillier SC. Pharmacology and physiology in anesthetic practice, ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Townsend CM, et al. Sabiston textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. ed 19. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012.