40 Care of the gastrointestinal, abdominal, and anorectal surgical patient

Antrectomy: Removal of the distal part of the stomach.

Appendectomy: Removal of the vermiform appendix, performed with an open or laparoscopic technique.

Cholecystectomy: Removal of the gallbladder; the procedure can be performed with an open or a laparoscopic approach.

Cholecystostomy: Placement of a tube or drain into the gallbladder to permit drainage of the organ, and rarely can be used to remove stones. This procedure is performed infrequently except to provide relief in a patient with cholecystitis who has prohibitive operative risk precluding cholecystectomy. This procedure is usually performed percutaneously in the radiology suite.

Colostomy: Colon brought through the abdominal wall to drain into a drainage device (bag); may be permanent or temporary, single or double lumen. May be performed with either an open procedure or a laparoscopic approach.

Diverticulum: A herniation of mucosa or submucosa through a weakness in a muscular wall of the colon, most commonly in the sigmoid colon, but may be found throughout the colon.

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): A side-viewing fiberoptic endoscope is used to cannulate pancreatic and biliary ducts through the ampulla of Vater for cholangiography, pancreatography, stone removal, and invasive manipulation such as sphincterotomy.

Endoscopy: Visualization of a body cavity with a lighted tube or scope. Most commonly performed to visualize the inside of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum or colon.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): Passage of a fiberoptic endoscope, usually with topical anesthesia and intravenous sedation, to view the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. Biopsies or control of bleeding may also be performed with this procedure.

Esophagoscopy: Direct visualization of the esophagus and cardia of the stomach by means of a rigid or flexible lighted instrument (esophagoscope). Esophagoscopy can be used to obtain a tissue biopsy or secretions for study to aid in diagnosis.

Gastrectomy: Removal of the stomach. If less than a total gastrectomy is performed, in which only part of the stomach is removed, the procedure is typically described as distal gastrectomy, proximal gastrectomy, or subtotal gastrectomy, suggesting only a small proximal gastric remnant remains. Total gastrectomies are most commonly performed for cancers in the proximal part of the stomach.

Gastroscopy: Direct inspection of the stomach with possible removal of a tissue specimen by means of a lighted instrument (gastroscope); bleeding can also be controlled and biopsy specimens can be obtained with this procedure.

Hemorrhoidectomy: Surgical excision of dilated veins of the rectum.

Hernia: The displacement of any viscus (usually bowel) or tissue through a congenital or acquired opening or defect in the wall of its natural cavity, most commonly the muscular wall of the abdomen. Usually this term is applied to protrusion of abdominal viscera; however, it is actually the defect itself through which abdominal contents have protruded.

Herniorrhaphy: Repair of a hernia. Hernias are classified according to anatomic site and condition of the viscus that has protruded. Reducible hernias are those in which the bowel or contents of the hernia sac can be replaced into the normal cavity. An irreducible, or incarcerated, hernia is one in which the contents cannot be replaced. A strangulated hernia is one in which the blood supply to the protruding segment of bowel is obstructed. When a segment of bowel becomes strangulated, it rapidly becomes necrotic. A strangulated hernia constitutes a surgical emergency. Hernias can be repaired with an open or laparoscopic technique.

Herniorrhaphy, Diaphragmatic: Replacement of abdominal contents that have entered the thorax through a defect in the diaphragm and repair of the diaphragmatic defect.

Herniorrhaphy, Epigastric and Hypogastric: Repair and closure of the abdominal wall defect.

Herniorrhaphy, Femoral: A defect in the region of the femoral ring, which is located just below the Poupart (inguinal) ligament and medial to the femoral vein. Femoral hernias are seldom found in children and occur most often in women.

Herniorrhaphy, Incisional: Repair of a defect in the abdominal wall that was a prior site of placement of a surgical incision. These types of repairs commonly involve placement of prosthetic (synthetic) mesh (e.g., Prolene, Gore-Tex, Parietex).

Herniorrhaphy, Inguinal: Repair of a defect in the inguinal region; may be direct (through Hesselbach triangle) or an indirect (through the internal ring) inguinal hernia. These repairs also commonly use some type of prosthetic mesh, most commonly Prolene or Parietex.

Herniorrhaphy, Umbilical: Reconstruction of the abdominal wall beneath the umbilicus (umbilical ring) can occur in pediatric patients and is most common in African American infants. In children, this hernia often closes spontaneously in infants before 2 years of age; therefore these repairs should generally not be performed until after the age of 2 years. Umbilical hernias in adults will never resolve spontaneously.

Ileostomy: Terminal ileum brought through the abdominal wall to empty into a drainage device (bag). Commonly used to treat inflammatory conditions of the bowel, such as ulcerative colitis and regional enteritis (Crohn disease), and to provide a permanent or temporary stoma after surgery for obstruction or cancer.

Intussusception: Telescoping of the bowel into itself.

Laparoscopy (Peritoneoscopy): Direct visualization of the peritoneal cavity by means of a lighted instrument (often connected to a color video monitor) inserted through the abdominal wall via a trocar placed through a small incision. An increasing number of abdominal procedures are performed assisted via laparoscopic techniques. Gastrointestinal or abdominal procedures commonly performed via laparoscopy include cholecystectomy, gastrojejunostomy, splenectomy, Nissen fundoplication, inguinal herniorrhaphy, appendectomy, jejunostomy, colostomy, colectomy, ileocolectomy, and pancreatectomy.

Laparotomy (Celiotomy): An opening made through the abdominal wall into the peritoneal cavity, to perform an operation in the abdomen in an open fashion (e.g., not laparoscopic).

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple Procedure): Removal of the head of the pancreas, the entire duodenum, the gallbladder, a portion of the jejunum, the distal third of the stomach, and the lower half of the common bile duct, with reestablishment of continuity of the biliary, pancreatic, and gastrointestinal systems. The procedure, which is used primarily for the treatment of malignant disease of the pancreas, duodenum, and ampulla, is associated with a less than 3% risk of perioperative mortality if performed in a high volume center. Sometimes a pylorus-sparing procedure is performed, which leaves the entire stomach intact.

Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG): Endoscopic procedure for the insertion of a tube into the stomach, either for the purpose of decompression or feeding, performed with local anesthesia and intravenous sedation.

Pyloromyotomy (Fredet-Ramstedt Operation): Enlargement of the lumen of the pylorus with longitudinal splitting of the hypertrophied circular muscle without severing of the mucosa; used as treatment for pyloric stenosis in infants. Pyloric stenosis is most common in firstborn male infants.

Pyloroplasty: A longitudinal incision made in the pylorus (full thickness) and closed transversely to permit the muscle to relax and establish an enlarged outlet. Heineke-Mikulicz is the most common type of procedure.

Splenectomy: Removal of the spleen; can be performed in an open or minimally invasive approach.

Transduodenal Sphincteroplasty: Partial division of the sphincter of Oddi and exploration of the common bile duct for treatment of recurrent attacks of acute pancreatitis caused by formation of calculi in the pancreatic duct or blockage of the sphincter of Oddi. Can also be used in treatment of biliary stones which cannot be removed by endoscopic or percutaneous means.

Volvulus: Intestinal obstruction as a result of twisting of the bowel, most commonly sigmoid colon or cecum.

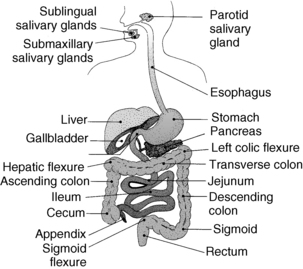

Care of the patient after abdominal surgery or surgery on the gastrointestinal tract is an extremely broad subject. Surgical intervention within the abdominal cavity is generally directed toward restoring normal function and therefore involves repair of congenital abnormalities, reconstruction of deformities, removal of obstructions to restore patency of the gastrointestinal tract and the biliary tract, treatment of malignant disease, and maintenance of the integrity of related organs, such as the liver, pancreas, and spleen (Fig. 40-1).

FIG. 40-1 Digestive system and its associated structures.

(From Sole ML, et al: Introduction to critical care nursing, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.)

General care after abdominal surgery

Abdominal or gastrointestinal surgery can be performed with regional or general anesthesia. The choice of anesthesia varies with the type of procedure, the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary status, and the surgeon’s need for muscle relaxation. Usually only short, simple procedures are performed with regional (spinal or epidural) anesthesia. Diagnostic procedures such as endoscopy, biopsy, and percutaneous gastrostomy often are performed with sedation only. Inguinal or femoral herniorrhaphies are often performed with regional (spinal) or general anesthesia, and occasionally with only local anesthesia. Most other abdominal surgical and laparoscopic procedures are performed with general anesthesia. All laparoscopic procedures require general anesthesia because of the need for relaxation of the abdominal wall and the need to control the patient’s respirations.

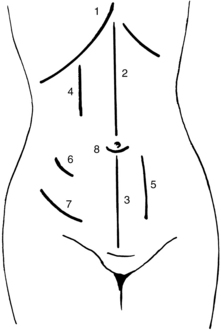

A number of abdominopelvic incisions have been developed and are commonly used (Fig. 40-2). An ideal incision ensures ease of entrance, maximal exposure of the operative site, and minimal trauma. It should also provide good primary wound healing with maximal wound strength.

The reader should review Chapters 26 through 31 for general care after surgery. See Chapter 45 for a discussion on bariatric surgical procedures and care.

Perianesthesia care

Dressings and drains

All tubes should be connected to the appropriate drainage devices, usually straight-gravity or closed-bulb suction drainage, as the surgeon specifies. Nasogastric tubes will usually be attached to constant or low intermittent wall suction. Maintenance of the patency of these tubes is one of the most important nursing functions after gastrointestinal surgery. Irrigation of nasogastric tubes after esophageal or gastric surgery should be directed by the surgeon’s orders.

Fluid and electrolyte balance

Fluid and electrolyte shifts or losses can be substantial during gastrointestinal surgery. Losses continue after surgery through gastrointestinal tubes or other drains, and through third-spacing of fluid into the abdomen. For this reason, accurate intake and output records are mandatory. This recording begins with the intake and output report from the anesthesia care provider, which should be the first PACU entry. All drainage from incisions should be included in the assessment of electrolyte balance. Frequent serum electrolyte determinations may be necessary if losses are great. Intravenous fluids are used for replacement for at least the first 24 hours after surgery and at least until the nasogastric tube is removed. See Chapter 14 for a discussion of the specific problems in electrolyte loss from the gastrointestinal tract.

Care of the patient with nasogastric or intestinal tubes

If gastric decompression is needed, short tubes are generally used; long intestinal tubes are no longer used. Short tubes used include the Levin and the plastic Salem sump, which is a double-lumen nasogastric tube and is the most commonly used tube. The double lumen prevents excessive negative pressure from developing when the tube is connected to suction. To benefit from the double-lumen tube, however, it is important that the lumen to air is not obstructed and is “sumping,” or the tube will become obstructed by sucking on the gastric wall.1

When the patient returns from the operating suite with a nasogastric tube in place, the nurse must ascertain why the tube was placed, where it was placed, and whether it should be connected to suction or to straight-gravity drainage. The physician often orders the tube to be connected to low-pressure intermittent suction (20 to 80 mm Hg). Usually only low-pressure intermittent suction is used, because excessive negative pressure in either the stomach or the bowel pulls the mucosa into the lumen of the tube and can cause traumatic ulcers. For double-lumen nasogastric tubes, continuous suction at 40 to 60 mm Hg is usually ordered and is necessary for the tube to function properly. Keeping the open lumen above the midline improves functioning of the double-lumen tube.

Patient comfort

Gargling with warm tap water or warm saline solution (or with viscous lidocaine or applications of a local anesthetic spray) can relieve the patient’s sore throat. A physician’s order should be provided for these measures. Some surgeons allow patients to suck on isotonic ice chips or hard candy or to chew gum. Anesthetic throat lozenges, if allowed, may be comforting to the patient. All patients with a gastrointestinal tube in place are given essentially nothing by mouth until the tube is removed. The only exception may be certain medications, given orally or through the tube, or ice chips (less than 200 mL every 8 hours). Some surgeons believe that allowing patients to consume ice chips increases comfort and also helps to keep the tube patent by having the melted ice chips frequently sucked out of the stomach by the tube.

Care after surgery on the gastrointestinal tract

Esophagus

Postoperative care depends on the kind of incision used to expose the operative site: abdominal, thoracic, or laparoscopic. Surgery on the esophagus frequently involves a thoracic incision. Care for the patient after a thoracic incision is discussed in Chapter 34. Procedures involving the esophagus are performed with general anesthesia.

A nasogastric tube is in place and should be cared for as previously discussed. The nurse should not manipulate the tube. Chest tubes should be managed as discussed in Chapter 34. A large, sterile dressing should be in place and should be checked frequently for drainage and reinforced as necessary. Excessive bloody drainage should be reported to the surgeon.

Stomach

Surgery on the stomach involves procedures to treat the complications of ulcers (e.g., pyloroplasty, gastric resection, gastrectomy), removal of portions of the stomach for malignant disease, and rerouting of the gastrointestinal system at this point to treat pyloric obstruction. In addition, gastric restrictive procedures for the treatment of clinically severe obesity (bariatric surgery) are also performed commonly (see Chapter 45). These procedures can be conducted as both open and laparoscopic procedures. All postoperative care of the patient is generally the same, and anesthesia is general.

After surgery, the patient should be placed in a semi-Fowler position to relieve tension on the abdominal wall suture line, to prevent aspiration, and to promote drainage. When the patient’s condition is hemodynamically stable, the obese patient (e.g. a patient requiring bariatric surgery) may benefit from positioning in a reverse Trendelenburg position at 45 degrees to maximize respiratory effort and decrease the effects of the abdominal weight interfering with adequate ventilatory effort. For open procedures, the abdominal incisions are fairly high, long, and painful; particular attention must be paid to pulmonary toilet. This patient must be encouraged more often than any other to expand the lungs and to cough and must generally have assistance to change position. Assistance in splinting the wound with the hands or with a firm pillow is usually appreciated by the patient. These procedures generally produce considerable postoperative pain, and analgesics should be used generously but judiciously. Patient-controlled or continuous epidural analgesia may be effective for upper abdominal incisional and visceral pain. Patients who have diagnosed or may have obstructive sleep apnea or obesity hypoventilation syndrome are extremely sensitive to opioid analgesics.2 Cautious administration and vigilant monitoring are essential, especially in these patients, to avoid respiratory depression and complications.

Bariatric gastric surgery

After bariatric procedures, the nurse should also be aware of the risk of leaks that occur with anastomoses or staple lines on the stomach. Leaks may occur and can be fatal if unrecognized. Symptoms of leaks range from abdominal tenderness, left shoulder pain, tachycardia, decreased urine output, fever, elevated white blood cell counts, oxygen desaturation, or a patient’s anxiety (e.g., sense of impending doom). It is important to note that morbidly obese patients often do not manifest signs of intraabdominal catastrophe in expected ways; often tachycardia is the only sign. The surgeon should be notified immediately if any of these signs or symptoms occur. See Chapter 45 for a detailed discussion on bariatric surgical procedures and care.

Small bowel

The patient with an ileostomy enters the PACU with a bag in place over the stoma. The condition of the stoma should be pink and moist. Returns may be expected almost at once and should be recorded. Particular attention must be paid to this stoma, the drainage, and the collection device; no leakage onto the skin should be allowed because this causes significant skin irritation. Under the collection device, the peristomal skin is protected with a skin barrier that includes pectin-based and karaya-based wafers or paste.

Large bowel

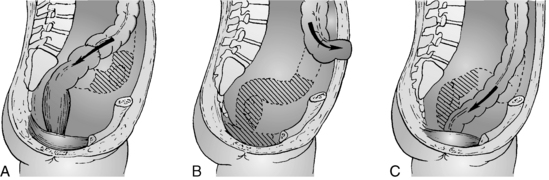

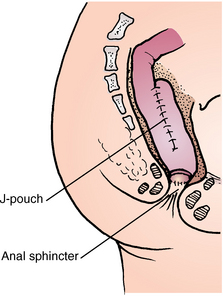

Surgery on the large bowel includes appendectomy, colostomy, various types of colonic resection for removal of tumors or correction of other problems, total proctocolectomy with ileostomy or ileoanal anastomosis (Fig. 40-3), and abdominoperineal resection with permanent colostomy (Fig. 40-4). Most of these surgical procedures are performed with general anesthesia. On return to the PACU, patients are kept flat and on one side until the reflexes have returned; they may then assume a position of comfort unless otherwise specified by the surgeon. Specifically after abdominoperineal resection, patients should not have any direct pressure on their perineal wounds. Postoperative care is essentially the same as for small bowel surgery.

FIG. 40-3 Ileoanal anastomosis with J-pouch for treatment of ulcerative colitis.

(From Black JM, Hokanson Hawks JH: Medical-surgical nursing: clinical management for positive outcomes, ed 8, St. Louis, 2008, Saunders.)

Implications for practice

When patients are undergoing colorectal surgery, there is no evidence to support the use of mechanical bowel preparation. The bowel cleaning can be omitted without compromising patient safety. Further study is warranted in these patients.

Source: Guenaga KF et al: Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD001544, 2005.

Appendectomy and herniorrhaphy

Patients who have undergone surgery for appendectomy or herniorrhaphy usually return to the PACU almost fully awake and without serious postoperative complications. Generally, no nasogastric tube, indwelling urinary catheter, or drain is in place, and recovery is generally uneventful. However, patients who have large ventral hernia repairs with mesh may have nasogastric tubes and drains in place. Patients can assume a position of comfort as soon as pharyngeal reflexes have returned, and they can start a progressive diet as tolerated unless a nasogastric tube is in place. All the postoperative care outlined in Chapters 26 through 31 is applicable. When the laparoscopic approach is used, general anesthesia usually is given. Patients may have shoulder pain or bloating because of insufflation of air. They may also have sore throat from intubation and the neuromuscular blocking agents. Monitor fluid intake and replace fluid losses appropriately. Dressings should remain dry and intact, and any postoperative incisional bleeding or drainage should be reported to the surgeon. The most important postoperative complication is bleeding. The nurse should also watch for urinary retention. If the patient has undergone inguinal hernia repair, the nurse should watch for development of scrotal edema or hematoma, which may indicate slow bleeding from the operative site.

Lower rectum and anus

Surgery on the lower rectum and anus includes excision of pilonidal cysts, rectal fissures, fistulas, rectal abscesses, tumors, and hemorrhoids. Perianesthesia nursing care is the same as for any patient who undergoes local, regional, or general anesthesia. Dressings should be checked frequently for excessive drainage and bleeding. The incisions may be closed, but often are packed to facilitate drainage of infected material and aid in healing. Urinary retention can be a problem because the proximity of the bladder and operative site can make urination difficult. Pain can be severe, but patients are often embarrassed by the location of the operative site and might not ask for analgesia. The nurse should be alert to signs and symptoms of pain and discomfort and administer analgesia as necessary for relief.

Surgery on related organs within the abdominal cavity

Liver

Open or laparoscopic surgery on the liver for the excision of tumors or the repair of lacerations is done with general anesthesia and, if open, involves a fairly long upper abdominal vertical or bilateral subcostal oblique (chevron) incision. Liver transplantation may be indicated in patients with end-stage liver disease, fulminant acute liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma, and pediatric metabolic liver diseases when a patient meets established criteria.3 The transplanted liver may be from a living donor or cadaver. All care previously discussed for patients after general anesthesia and upper abdominal incisions applies. Respiratory care is of paramount importance. The liver is an extremely vascular organ. It is difficult to suture; gross bleeding is common and often involves large blood losses, especially when surgery is necessitated by traumatic injury or large resection. Large drains of the suction (grenade or bulb) type are placed in the region of the laceration or excision of the tumor and are brought through separate sites to the skin surface. For the first 8 hours, expect approximately 100 to 250 mL of serosanguineous drainage from the drains.

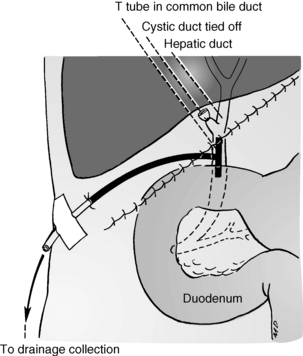

Vital signs must be assessed frequently, and any downward trend should be reported to the surgeon at once. Blood replacement or hemostasis may be inadequate. Rapid infusions of fluid replacements may be needed, especially after extensive liver resection or transplant. Occasionally, this patient also has a T-tube in place in the common bile duct (Fig. 40-5). This tube should be attached to straight-gravity drainage, and accurate measurements of the output should be made. A nasogastric tube is often in place and should receive care as discussed previously. Pain may be severe, and opioid analgesics or epidural analgesia are necessary to promote rest and respiratory effort.

Spleen

Surgery on the spleen involves general anesthesia and removal of the organ, with either an open or laparoscopic technique. The spleen is removed because of rupture from trauma; accidental trauma from associated surgery; diseases that cause damage, such as mononucleosis and malaria; a variety of hematologic diseases; left-sided portal hypertension; and hypersplenism. If the procedure is done with an open technique, a midline or left subcostal incision is used. Postoperative care for the patient after splenectomy is the same as that for the patient after repair of a lacerated liver. Dressings should remain dry and intact. A drain may be placed in the subdiaphragmatic space to prevent the collection of blood under the diaphragm and to detect unrecognized injury to the pancreas that may have occurred.

Pancreas

Frequent assays of blood glucose levels should be ordered for all patients after pancreatic surgery. Most of these patients need to receive intravenous insulin during the postoperative period. Generally, insulin doses are titrated to maintain the blood glucose levels between 140 and 180 mg/dL in the critical care setting and at less than 140 mg/dL in the noncritical care setting.4 The insulin aids in preventing hyperglycemia.

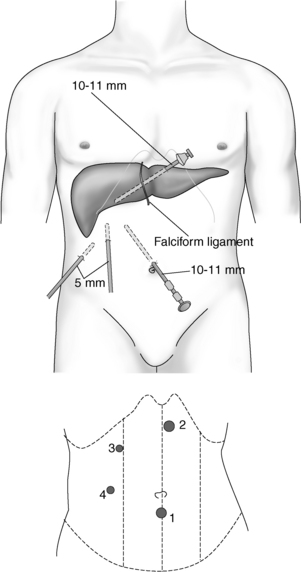

Biliary tract

Surgery on the biliary tract includes exploration for removal of stones from the gallbladder and the ducts and removal of the gallbladder. It can also include repair of biliary tract injuries and resection for malignant disease or benign strictures. Anesthesia is general, regional, or a combined technique. For cholecystectomy, the procedure is performed with a laparoscope, the patient has an umbilical incision and three small subcostal incisions for instruments (Fig. 40-6); if performed open, the incision is either a right subcostal or a midline incision. On return to the PACU, the patient is placed in a semi-Fowler position. All tubes must be cared for appropriately. A nasogastric tube is typically placed during surgery and is often removed when the operative procedure ends. A T-tube is placed in the common bile duct if the common duct was opened during surgery. This tube is usually connected to straight-gravity drainage to a bile bag. Careful attention must be paid to maintaining the patency of this tube and its attachment to the patient; the surgeon needs to be called immediately if the tube is dislodged.

FIG. 40-6 Placement of laparoscope and instrument ports for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

(Redrawn from Malt RA: The practice of surgery, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

After laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the patient may have one of the most stable conditions of any seen in the PACU. Any patient with unexplained pain, oliguria, or hypotension should be immediately discussed with the surgeon. Complications of gas embolism, deep vein thrombophlebitis, subcutaneous emphysema, injuries to major vessels and intestine, and bile leakage all have been reported after laparoscopic procedures. Right shoulder pain is often experienced because of the referred pain from a nerve running up from the diaphragm; however, this resolves fully within 72 hours.

Summary

This chapter discussed the care involved after surgery on the gastrointestinal tract, including the esophagus and the anus, and the accessory organs: the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and spleen. Surgery on the female reproductive organs, which are also contained within the abdominal cavity, is reviewed in Chapter 42. The care common to all patients undergoing abdominal surgery was discussed, and only the most important variations related to specific procedures were included.

1. Altman GB, et al. Fundamental and advanced nursing skills, ed 3. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar; 2010.

2. Gross JB, et al. Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology.2006;104(5):1081–1093.

3. DuBay DA, Sung RS. Liver transplantation. In Minter RM, Doherty GM: Current procedures: surgery. available at: www.accesssurgery.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/content.aspx?aID=6563318, January 5, 2012. Accessed

4. Moghissi ES, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Endocr Prac. 2009;15(4):353–369.

Black JM, Hokanson Hawks JH. Medical-surgical nursing: clinical management for positive outcomes. ed 8. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.

O’Brien D. Gastrointestinal Care. Schick L, Windle PE. Perianesthesia nursing core curriculum: preprocedure phase I and phase II PACU nursing. ed 2. St. Louis: Saunders; 2010.

Nagelhout JJ, Plaus KL. Handbook of nurse anesthesia, ed 4. St. Louis: Saunders; 2010.

Rothrock JC. Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 14. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011.

Townsend CM, et al. Sabiston textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. ed 18. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008.