43 Care of the breast surgical patient

Adenocarcinoma: A general type of cancer that starts in glandular tissues anywhere in the body. Almost all breast cancers start in glandular tissue of the breast and therefore are adenocarcinomas. The two main types of breast adenocarcinomas are ductal carcinomas and lobular carcinomas. Benign breast lesions are the most commonly excised lesions (fibrocystic changes and fibroadenomas).

Augmentation Mammoplasty: Surgery to enlarge or augment the size of the female breast with a breast implant; the most popular cosmetic procedure.

Breast Biopsy: Excision of breast tissue. The specimen is sent to the pathology laboratory for frozen sectioning. In addition, a needle localization can be performed when a suspected lesion is identified with mammogram results. The procedure involves placing a thin needle or guide into the breast with mammographic visualization. The lesion is then excised and taken to the pathology laboratory for frozen sectioning to determine a diagnosis.

Breast Reconstruction (Mammoplasty): The breast is reconstructed after mastectomy.

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS): Ductal carcinoma in situ (also known as intraductal carcinoma) is the most common type of noninvasive breast cancer. Cancer cells are inside the ducts, but have not spread through the walls of the ducts into the fatty tissue of the breast. Nearly all women diagnosed at this early stage of breast cancer can be cured. The best way to find DCIS is with a mammogram. With more women getting mammograms each year, diagnosis of DCIS is becoming more common. DCIS is sometimes subclassified based on its grade and type to help predict the risk of return of cancer after treatment and to help select the most appropriate treatment. Grade refers to how aggressive cancer cells appear with a microscope. Several types of DCIS exist, but the most important distinction among them is whether tumor cell necrosis (areas of dead or degenerating cancer cells) is present. The term comedocarcinoma is often used to describe a type of DCIS with necrosis.

Infiltrating (or Invasive) Ductal Carcinoma (IDC): With a start in a milk passage, or duct, of the breast, this cancer has broken through the wall of the duct and invaded the fatty tissue of the breast. At this point, it has the potential to metastasize, or spread, to other parts of the body through the lymphatic system and bloodstream. Infiltrating ductal carcinoma accounts for approximately 80% of invasive breast cancers.

Infiltrating (or Invasive) Lobular Carcinoma (ILC): ILC starts in the milk-producing glands. Similar to IDC, this cancer has the potential to spread (metastasize) elsewhere in the body. Approximately 10% to 15% of invasive breast cancers are invasive lobular carcinomas. ILC may be more difficult to detect with mammogram than IDC.

Inflammatory Breast Cancer: This rare type of invasive breast cancer accounts for approximately 1% of all breast cancers. In inflammatory breast cancer, the skin of the breast appears red and feels warm, as though it were infected and inflamed. The skin has a thick, pitted appearance that doctors often describe as resembling an orange peel. Sometimes the skin develops ridges and small bumps that resemble hives. Doctors now know that these changes are not caused by inflammation or infection, but the name given long ago to this type of cancer still persists. Cancer cells that block lymph vessels or channels in the skin over the breast cause these symptoms.

In Situ: This term is used for an early stage of cancer in which it is confined to the immediate area at which it began. Specifically in breast cancer, in situ means that the cancer remains confined to ducts (ductal carcinoma in situ) or lobules (lobular carcinoma in situ). It has not invaded surrounding fatty tissues in the breast nor spread to other organs in the body.

Lobular Carcinoma In Situ (LCIS): Although not a true cancer, LCIS (also called lobular neoplasia) is sometimes classified as a type of noninvasive breast cancer. It begins in the milk-producing glands, but does not penetrate through the wall of the lobules. Most breast cancer specialists think that LCIS itself does not become an invasive cancer, but that women with this condition have a higher risk of developing an invasive breast cancer in the same or the opposite breast. For this reason, women with LCIS should have physical examinations two or three times per year and an annual mammogram.

Lumpectomy: Only the tumor and surrounding tissue of a “breast lump” are excised. The rest of the breast remains intact. The procedure includes dissection of the axillary lymph nodes. The lump is generally smaller than 4 cm in diameter.

Mastopexy (Breast Lift): Reshaping (uplifting) the sagging breasts with surgical tightening of the skin.

Medullary Carcinoma: This special type of infiltrating breast cancer has a relatively well-defined distinct boundary between tumor tissue and normal tissue. It also has some other special features, including the large size of the cancer cells and the presence of immune system cells at the edges of the tumor. Medullary carcinoma accounts for approximately 5% of breast cancers. The outlook, or prognosis, for this kind of breast cancer is better than for other types of invasive breast cancer.

Modified Radical Mastectomy: Removal of the entire breast and axillary lymph nodes; the pectoralis major muscle is left intact. In some instances, the pectoralis minor muscle is excised.

Mucinous Carcinoma: This rare type of invasive breast cancer is formed by mucus-producing cancer cells. The prognosis for mucinous carcinoma is better than for the more common types of invasive breast cancer. Colloid carcinoma is another name for this type of breast cancer.

Paget Disease of the Nipple: This type of breast cancer starts in the breast ducts and spreads to the skin of the nipple and then to the areola, the dark circle around the nipple. It is a rare type of breast cancer and occurs in only 1% of all cases. The skin of the nipple and areola often appears crusted, scaly, and red with areas of bleeding or oozing. Women may notice burning or itching. Paget disease may be associated with in situ carcinoma or with infiltrating breast carcinoma. If no lump can be felt in the breast tissue and the biopsy shows DCIS but no invasive cancer, the prognosis is excellent.

Phyllodes Tumor: This rare type of breast tumor forms from the stroma (connective tissue) of the breast, in contrast to carcinomas, which develop in the ducts or lobules. Phyllodes (or hylloides) tumors are usually benign but rarely malignant, with the potential to metastasize. Benign phyllodes tumors are successfully treated by removing the mass and a narrow margin of normal breast tissue. A malignant phyllodes tumor is treated with removal along with a wider margin of normal tissue or with mastectomy. These cancers do not respond to hormonal therapy and are not so likely to respond to chemotherapy or radiation therapy. In the past, both benign and malignant phyllodes tumors were called cystosarcoma phyllodes.

Radical Mastectomy: Removal of the entire breast, skin, nipple, areolar complex, and pectoralis major and minor muscles with axillary node dissection.

Tubular Carcinoma: Tubular carcinomas are a special type of infiltrating breast carcinoma and account for approximately 2% of all breast cancers. They have a better prognosis than usual infiltrating ductal or lobular carcinomas.

Breast cancer, the most common cancer in women,1 is a malignant tumor that develops from cells of the breast. Although breast cancer in men is rare, it does occur. With the newer forms of treatment of cancer of the breast, including improved forms of diagnosis, surgical procedures on the breast have increased. However, with earlier breast cancer diagnosis and with the advent of enhanced radiation and chemotherapy protocols, surgical procedures performed on the breast might not be as extensive as in years past. All women are at risk for breast cancer. The two most significant risk factors are female gender and older age.2 Ninety-five percent of new cases and 97% of breast cancer deaths occurred in women older than 40 years.2 Risk of breast cancer also increases if the woman’s mother, sister, or daughter has had the disease. Breast surgery is most commonly performed on women; however, procedures are occasionally performed on men and children. In addition, nondisease breast procedures may be performed for cosmetic purposes. Breast cancer is the second leading cause of death for women after lung cancer.1 The chances of a woman having breast cancer are one in eight. Chances of dying from breast cancer are approximately 1 in 33. Breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer in African American women and the second leading cause of death in African American women, exceeded only by lung cancer. Approximately 1 in 100 men is expected to develop breast cancer in a lifetime. As the patient’s advocate, the perianesthesia nurse must be supportive, caring, and reassuring to the patient having breast surgery. Positive support is the start of the patient’s rehabilitation process. Early detections, self examination, mammography, and an increased public awareness are all important factors in decreasing annual breast cancer mortality.2 Breast cancer treatment today involves a combination of therapies, including surgical excision of the tumor, radiation therapy alone, or a combination of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. New studies and treatment protocols are continuously being developed and subjected to trials, but early detection remains the best hope for cure.

Surgical interventions and perianesthesia nursing care

Breast biopsy

For many of the female patients who undergo a biopsy, the diagnosis is fibrocystic disease. Fibrocystic disease describes a variety of benign and localized tumors or swelling within the breast tissues, including cysts, masses, and intraductal papillomas. Other nonfibrocystic conditions also may cause breast lumps. Inflammatory conditions, such as breast abscesses, fat necrosis, and lipomas of the skin (e.g., sebaceous cysts), can cause breast lumps.

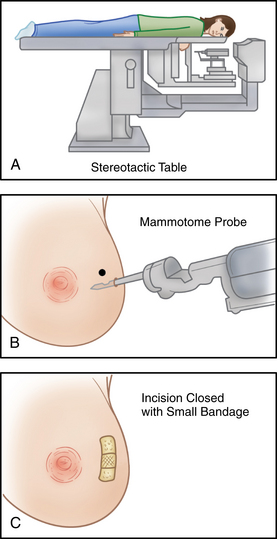

The patient is usually admitted as a same-day surgery patient. The patient may undergo needle biopsy, incisional biopsy, or excisional biopsy. A needle biopsy includes the introduction of a disposable cutting-type needle through the mass to entrap a core of tissue. The needle is withdrawn, and the specimen is sent to the pathology laboratory. In an incisional biopsy, a portion of the mass is surgically excised along a curved incision line. An excisional biopsy may be needed to remove the entire mass and some of the adjacent tissue around it for examination. A stereotactic procedure may be performed in which the patient lies face down on a special table. The breast protrudes through a hole in the table and is lightly compressed while the computer provides detailed diagnostic images. The biopsy area is located and a probe is inserted to remove the tissue specimens (Fig. 43-1).

Surgical choices for the treatment of cancer

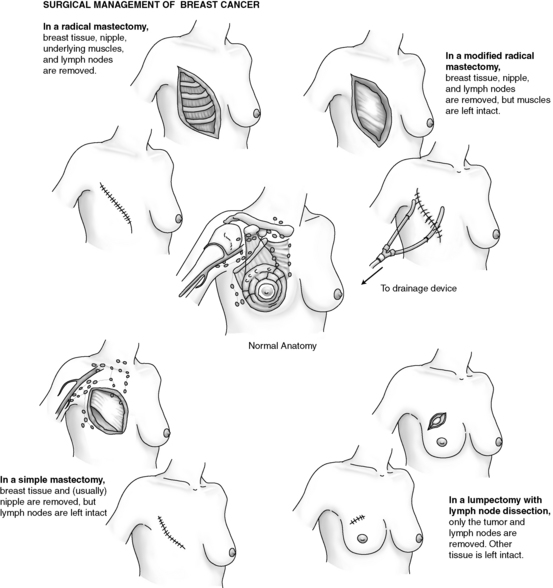

Most women need some type of surgery to treat the breast tumor and remove as much of the cancer as possible. Surgical treatment choice depends on the stage of the disease, the size and site of the mass, and the patient’s individual choice. Advances in early diagnosis and modifications in surgical techniques have increased the number of surgical choices in the treatment of breast cancer (Fig. 43-2). Surgical treatment may range from breast-conserving techniques (lumpectomy) to modified radical mastectomy that involves the breast and the axillary nodes.

FIG. 43-2 Surgical choices for treatment of breast cancer.

(Redrawn from Ignatavicius DD, Workman ML: Medical-surgical nursing: critical thinking for collaborative care, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

Lumpectomy

Lumpectomy, also called breast-conserving therapy, is the surgical treatment of choice when the breast tumor is well defined and less than 5 cm in diameter. In landmark clinical trials reported in 1988, the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Cancer Project reported that lumpectomy followed by radiation therapy produced 8-year disease-free survival rates equal to those of modified radical mastectomy.3

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

A sentinel lymph node biopsy may be done to visually examine the lymph nodes without having to remove them first. Sentinel node biopsy was developed to reduce the morbidity associated with surgical staging of the axilla in patients with no palpable axillary nodes.3 A blue dye alone or in combination with a radiolabeled colloid dye is injected near the tumor and is carried by the lymph system to the first (sentinel) node to receive lymph from the tumor. This lymph node is most likely to contain cancer cells if the cancer has spread. The sentinel node is not located in the same site in every patient. When this node is found, it is removed and examined. If it is free of cancer, further surgery may not be needed. If there is evidence of positive nodes and axillary node dissection and adjunct therapy may be required. It is done through a separate incision and involves a sample of 10 to 15 lymph nodes lateral and inferior to the pectoralis minor muscles for pathology. Removal and examination of the nodes allows for staging of the cancer and helps the patient and provider to choose adjuvant therapy and treatment options. A possible side effect from the removal of the lymph nodes is lymphedema or swelling of the arm (seen in 1 to 3 of 10 women; Box 43-1).

BOX 43-1 Lymphedema

Clinical trials are underway to study the effectiveness of new treatments and therapies to reduce the incidence of lymphedema after breast cancer surgery. One current trial (CA:GB 70305) is investigating whether a combination of education, use of light arm weights with exercise, a light compression sleeve with vigorous activity, and regular breathing exercises can reduce the risk or severity of lymphedema after axillary lymph node dissection (www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/CALGB-70305).

Modified from Mohler III ER, Mondry TE: Patient information: lymphedema after breast cancer surgery, available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/patient-information-lymphedema-after-breast-cancer-surgery?source=search_ result&search=lymphedema&selectedTitle=5∼109. Accessed December 11, 2011.

When the patient is admitted to the PACU, all the initial assessment measures should be performed. The blood pressure cuff should be placed on the arm opposite the operative side. The arm on the operative side should be elevated on a pillow because the removal of lymph nodes increases the risk of lymphedema. The operative-side arm should be assessed frequently for circulatory adequacy with monitoring of color, temperature, capillary refill, and the presence and strength of the radial pulse. Venipunctures and injections should not be performed on the operative-side arm. Sentinel node biopsy is usually an outpatient procedure that allows rapid return to full mobility and permits return to work weeks sooner than after axillary dissection.3 Dressings should be small, and bleeding or drainage should be minimal. A Hemovac or Jackson-Pratt closed-drainage system may be connected to drains placed at the incision site, but with a sentinel node biopsy are seldom required.

Mastectomy

Partial (segmental) mastectomy

The partial mastectomy involves the removal of more of the breast tissue than in the lumpectomy and is usually followed by radiation therapy. Some surgeons refer now to lumpectomy or partial mastectomy as a wide local excision.3

Modified radical mastectomy

The modified radical mastectomy is the most commonly performed surgery for elimination of breast cancer. The entire involved breast and axillary, pectoral, and superior apical nodes are removed. The underlying pectoral muscles are not removed. The modified radical mastectomy is performed with hopes of decreasing the chance of the malignancy spreading.

Radical mastectomy

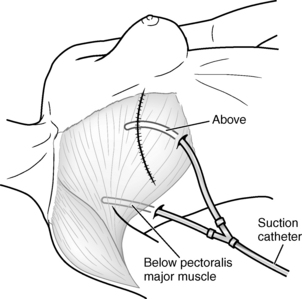

Mastectomy is performed with general anesthesia. The patient is admitted to the Phase I PACU, with the head of the bed elevated 30 to 45 degrees. Admission assessments are performed per PACU protocol. Dressings may be bulky and should be checked frequently for excessive serosanguineous drainage and for constriction. Patients should be observed closely for signs of postoperative hematoma below the skin flaps. Attention to the drains and the maintenance of free drainage within the vacuum system prevent this potential complication. Drains are usually placed under the skin flaps to remove excess blood and serum that ordinarily collect under the wound site, thus causing edema, infection, and sloughing of the skin graft (Fig. 43-3).4 The drains may be connected to Hemovac or Jackson-Pratt devices or some other closed suction device. Generally, additional vacuum is needed the first 8 postoperative hours, and the Hemovac is connected to vacuum pressure of 20 to 30 mm Hg. These drains should be monitored for excessive bleeding, which must be reported to the surgeon. Dressings are necessarily snug, but should not impair respiration or circulation to the upper extremity. The arm on the operative side should be supported and elevated on a pillow; it must be checked frequently for cyanosis or pallor, and the pulse must be palpated for intensity. If signs of respiratory distress or impaired circulation arise, the surgeon should be notified to rearrange the dressing.

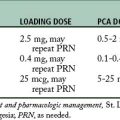

Patients usually need intravenous fluid augmentation for the first 24 postoperative hours. Oral feeding is allowed after cough and gag reflexes have returned and if nausea is not present. Small sips of fluids may be offered and taken as desired, and diet resumed as tolerated. Postoperative pain can be moderate to severe and can usually be controlled with opioids such as meperidine and morphine. The incidence of persistent postsurgical pain in patients who received breast surgery has been identified as much as 65%.5 With the increased preoperative use of paravertebral nerve blocks for breast surgery patients, pain management has been greatly enhanced, resulting in less need for opioids and improved patient satisfaction.6 Hypothermia may be a problem because of prolonged exposure in the operating room, and rewarming should be accomplished with additional warmed blankets or a forced warm air device. Postoperative instructions for patients who have axillary node dissections should include hand and arm care instructions. Consistent education and support are necessary. Emotional support may be sought through support groups such as the Reach to Recovery program (American Cancer Society: web site, www.cancer.org/; or telephone, 800-ACS-2345).

Implications for practice

Paravertebral block greatly improves the quality of recovery and pain relief after breast cancer surgery. Most patients receiving a PVB have less postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting. Perianesthesia nurses should be aware that these patients will have reduced opioid requirements and tolerate early ambulation or mobilization. Patients should be monitored for hypotension and signs and symptoms of pneumothorax.

Source: Boughey JC, et al: Improved postoperative pain control using thoracic paravertebral block for breast operations, Breast J 15(5):483-488, 2009.

Breast reconstruction

Breast reconstruction may be performed in a variety of methods in which the surgeon, in collaboration with a plastic surgeon, tailors the operation to the patient’s individual irregularity. Reconstructive options can be divided into two main types: those that use autogenous tissue and those that require alloplastic material.3 Breast reconstruction can be performed with three different techniques: available tissue with an implant, the use of tissue expanders, and the use of flaps. Use of the available tissue is the simplest procedure, but often sufficient tissue is not available after mastectomy. If enough tissue is available, an appropriately sized implant is placed under the remaining skin flap or muscle. The other breast may have its size adjusted with either a reduction mammoplasty or a mastopexy to achieve symmetry if necessary and the patient desires to do so. Autogenous methods of reconstruction give the best symmetry.3

Myocutaneous flap reconstruction (Figs. 43-4 and 43-5) involves moving nearby muscle and skin into the area of the mastectomy to replace the significant tissue deficiency after mastectomy. Commonly used muscle and skin flaps include the latissimus dorsi and rectus abdominis muscles with attached skin. Nipple-areola reconstruction can be accomplished with small portions of the labia and grafting to the selected location or areola reconstruction with tattooed pigment.3 Postoperative care is generally the same as for the patient who undergoes other types of breast surgery, with attention to graft and flap donor sites (see Chapter 44).

Mastopexy (breast lift)

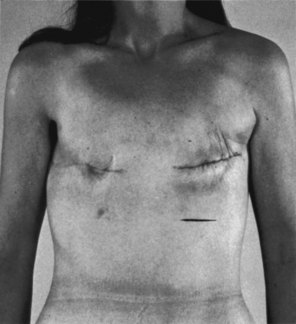

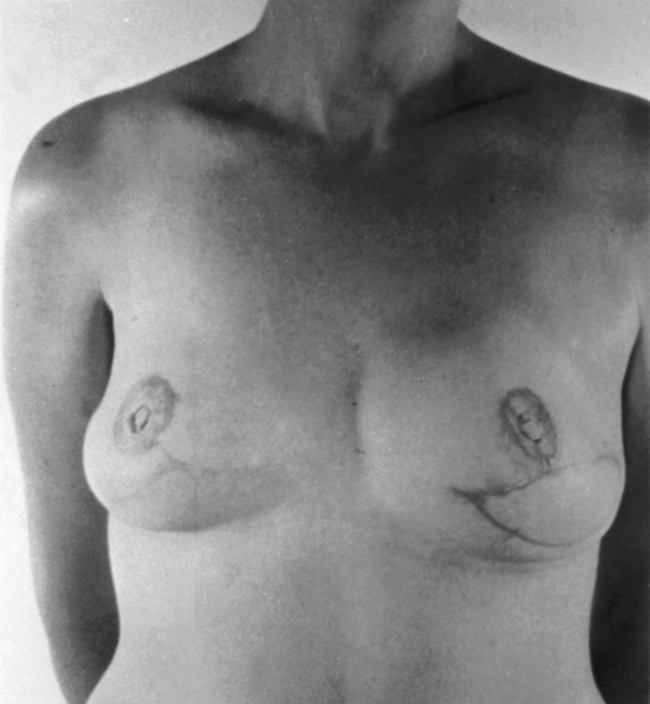

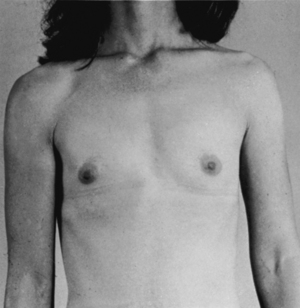

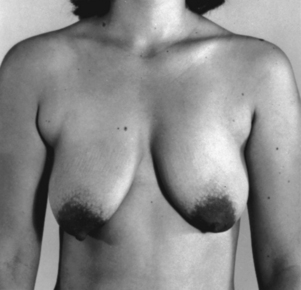

Breast ptosis (sagging) is defined by the position of the nipple areolar complex related to the inframammary crease. The reshaping process differs from reduction mammoplasty in the amount of tissue removed. There is usually minimal to no removal of breast tissue with use of a breast implant when needed.7 Generally less than 300 g of tissue removed is considered a mastopexy procedure (Figs. 43-6 and 43-7).

FIG. 43-6 Mastopexy (breast lift). Before surgery, this patient had sagging (ptosis) of the breasts.

FIG. 43-7 Mastopexy, showing same patient in Fig. 43-6 several weeks after surgery. Scars are beginning to fade.

Postoperative dressings are minimal, and drains are rarely necessary because the entire procedure, with the exception of nipple release, is at the level of the dermis. Drainage should be minimal, and if frank bleeding occurs, the surgeon should be notified. Pain is usually not a problem, and discomfort can be controlled with mild analgesics. Food and fluids may be resumed as tolerated after nausea has disappeared.

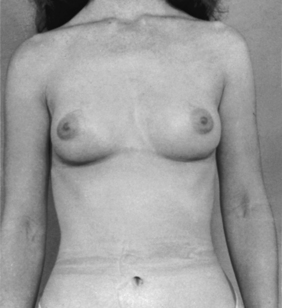

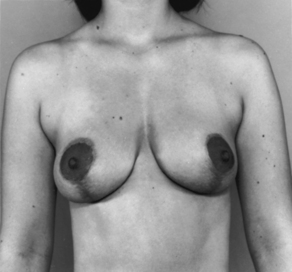

Augmentation mammoplasty

Breast augmentation is done for hypomastia, to correct breast asymmetry, to recreate the breast after mastectomy, or for the patient’s desired enhancement of breast size (Figs. 43-8 and 43-9).7 Incisions may be inframammary, axillary, or semicircular around the lower half of the areolar outline. The inframammary approach is the simplest, but the axillary incision provides the least visible scar after surgery. Breast implants can be placed beneath the mammary tissue or under the muscle layer of the chest. Many surgeons believe that positioning the implants beneath the muscle provides the patient with the most natural appearance. Breast augmentation can also be accomplished endoscopically with transluminal breast augmentation in which a small incision is made inside the navel. These patients have self-adhesive wound strips over the umbilical incision and are fitted with an elastic bandage.

Reduction mammoplasty

Reduction mammoplasty is the surgical method to correct gigantomastia or macromastia in which patients have back pain, breast pain, postural changes, or shoulder strap discomfort from the weight of the breasts.7 These women may also have an inability to participate in physical activities such as jogging, aerobics, and horseback riding. Breast reduction is performed with general anesthesia. Breast tissue and skin are excised; the nipple areolar complex is elevated superiorly on the new breast mound. Reduction mammoplasty is a lengthy procedure in which significant fluid and blood loss is anticipated. Because of the prolonged anesthesia and surgery time, some providers use a team approach to reduce the surgical time. Some patients donate autologous blood before this surgery, but all patients should have a blood type and screen before surgery. Frequently, intravenous crystalloids are all that is necessary for fluid replacement.

A newer method in reduction mammoplasty is the laser deepithelialization technique. When the carbon dioxide laser is used to remove the epidermis from the inferior pedicle, reduction mammoplasty can be performed with little blood loss. The inferior pedicle technique is a commonly used approach to reduction mammoplasty. When the inferior pedicle technique is used, the laser simplifies skin removal. The laser is preferred for pedicle deepithelialization in all patients, especially patients who have large ptotic breasts, because rigid stabilization is not necessary.

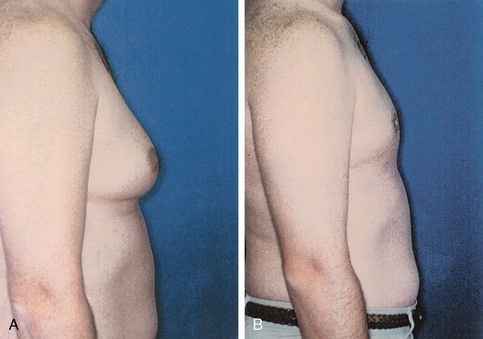

Surgery in gynecomastia

Gynecomastia, or benign hypertrophy of one or both breasts in boys and men, is relatively common (Fig. 43-10). The condition may be bilateral or unilateral. The causes may be hormonal, systemic disease-oriented, drug-related, or idiopathic.

FIG. 43-10 A, Preoperative view of gynecomastia. B, Postoperative view after excision of gynecomastia.

(From Rothrock J: Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 14, St. Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

Postoperative care is essentially the same as that for women who undergo breast surgery. If no drains are necessary, the patient can be discharged the day of surgery after reflexes have returned, nausea has subsided, and food and fluids can be taken.

Summary

A diagnosis of breast cancer can be overwhelming for both the patient and their family. Many facilities have hired breast care nurse navigators to offer support, answer questions, and “navigate” the patient through their journey.8 After breast surgery, patients need emotional support and encouragement to express concerns and fears. Patients should be provided with accurate and complete information in a hopeful and positive manner, yet they should not be given unfounded or unreasonable hopes and promises. The nurse navigator, as an educator and patient advocate, can be a single point of contact for the patient and their family. In addition, perianesthesia nurses should encourage patients to discuss their fears and feelings regarding their diagnosis and treatment and provide patients with detailed postoperative instructions (see Chapter 28). The web site for the American Cancer Society (www.cancer.org) can provide the patient with an abundance of information regarding breast cancer after care and support groups.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Cancer prevention and control. available at: www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/data/women.htm, December 31, 2011. Accessed

2. American Cancer Society: Breast cancer facts and figures 2011-2012. available at: www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-030975.pdf, December 31, 2011. Accessed

3. Townsend CM, et al. Sabiston textbook of surgery, ed 18. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008.

4. Pearsall EB. Breast surgery. Rothrock J, ed. Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 14, St. Louis: Mosby, 2011.

5. Pasero C. Persistent postsurgical and posttrauma pain. J Perianesth Nurs. 2011;26:38–42.

6. Boughey JC, et al. Improved postoperative pain control using thoracic paravertebral block for breast operations. Breast J. 2009;15(5):483–488.

7. Dreger V. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Rothrock J, ed. Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery. ed 14. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011.

8. Sein E, et al. Fox Chase Cancer Center partners develops orientation manual for breast care nurse navigators. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2009;36(3):45–46.

Barash P, et al. Clinical anesthesia, ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

Boughey JC, et al. Improved postoperative pain control using thoracic paravertebral block for breast operations. Breast J. 2009;15(5):483–488.

Elliott FL, et al. The scarless latissimus dorsi flap for full muscle coverage in device-based immediate breast reconstruction: an autologous alternative to acellular dermal matrix. Plast Reconstr Surg.2011;128:71–79.

Fisher B, et al. Eight-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing mastectomy and lumpectomy with or without radiation in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:822–828.

Ganong W. Review of medical physiology, ed 23. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2010.

Gutowski KA. Aesthetic and functional breast surgery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:337–345.

Hall J. Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology, ed 12. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2011.

Longnecker D, et al. Principles and practice of anesthesiology, ed 2. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998.

Mohler ER, Mondry TE. Lymphedema after breast cancer surgery. (website) www.uptodate.com/contents/patient-information-lymphedema, July 26, 2011. Accessed

Miller R, et al. Miller’s anesthesia, ed 7. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

Miller RD, Pardo M. Basics of anesthesia, ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2011.

Nagelhout J, Plaus K. Nurse anesthesia, ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2011.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer, version 1.2011. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf, July 31, 2011. Accessed

National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Guidelines for Patients: version 2.2011. available at: http://www.nccn.com/files/cancer-guidelines/breast/index.html, July 31, 2011. Accessed

St. Francis Health: Breast care nurse navigator. available at: www.stfrancishospitals.org/cancer, July 26, 2011. Accessed

Schick L, Windle PE. Perianesthesia nursing core curriculum: preprocedure, phase I and phase II PACU nursing. ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation: Breast cancer research. available at http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/BreastCancerResearch.html, December 30, 2011. Accessed