Chapter 16. Cardiovascular System

Rationale

Approximately 50% of all children have innocent heart murmurs. Screening and referral of children with murmurs assists in distinguishing between innocent and organic murmurs. Assessment of cardiac and vascular function is an essential component of many hospitalizations, particularly when surgery is performed and when drugs are administered. When cardiac problems have been identified, knowledgeable assessment aids in monitoring the effectiveness of treatment regimens and in early detection of complications.

Anatomy and Physiology

The heart is a muscular four-chambered organ located in the mediastinum. The upper chambers of the heart are the atria; the lower chambers are the ventricles. Septa divide the two ventricles and the two atria. Four valves prevent the backflow of blood into the chambers. The tricuspid valve, located between the right atrium and ventricle, and the bicuspid, or mitral valve, located between the left atrium and ventricle, are the atrioventricular valves. The pulmonic valve, located in the pulmonary artery, and the aortic valve, in the aorta, are the semilunar valves. Closure of the four valves produces vibrations that are thought to be responsible for heart sounds. S1 refers to the “lubb” sound produced by closure of the atrioventricular valves, and S2 to the “dubb” sound produced by closure of the semilunar valves. Table 16-1 summarizes the various sounds and their characteristics.

| Sound | Cause | Location | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 (lubb) | Mitral and tricuspid valves are forced closed at the beginning of systole (heart contraction). | Apex of heart | S1 is longer and lower pitched than S2. |

| Synchronous with carotid pulse. | |||

| Closure of valves usually heard as one sound, but slight asynchrony can produce audible splitting, best heard in the fourth left interspace. | |||

| S2 (dubb) | Aortic and pulmonic valves are forced closed at the beginning of diastole (heart relaxation). | Base of heart | Short, high-pitched S2 can be split during inspiration. Splitting is best heard in the aortic area. If the breath is held on inspiration, “physiologic split” is accentuated. |

| S3 | Vibrations are produced by rapid ventricular filling. | Apex of heart | Heard early in diastole. Dull, low pitched. |

| Normal in children and young adults. | |||

| S4 | Resistance to ventricular filling after contraction of atria. | Apex of heart | Low pitched. |

| Considered abnormal. Best heard when child is supine. |

In its initial stage of development the heart is a straight tube. Between the second and tenth weeks of gestation it undergoes a series of changes to become a four-chambered organ. The heart begins beating during the third week of gestation. During fetal life it primarily distributes the oxygen and nutrients that have been supplied through the placenta. The fetal lungs are largely bypassed by shunts that exist during fetal life. At birth these shunts begin to close as pulmonary vascular resistance drops. Pulmonary vascular resistance approximates adult levels by 6 weeks. Pulmonary vascular resistance is still relatively high in the first month of life, and cardiac defects such as ventricular septal defect might not be detected.

The heart is large in relation to body size in the infant. It lies somewhat horizontally and occupies a large portion of the thoracic cavity. Growth of the lungs causes the heart to assume a lower position, and by 7 years of age the heart has assumed an adult position that is more oblique and lower. Heart size increases in adolescence in conjunction with rapid growth.

At birth ventricular walls are similar in thickness, but with circulatory demands the left ventricle increases in thickness. The thinness of the ventricle produces a low systolic pressure in the newborn. The systolic pressure rises after birth until it approximates adult levels by puberty. Blood vessels lengthen and thicken in response to increased pressures.

Equipment for Assessment of Cardiovascular System

▪ Stethoscope (preferably with a small diaphragm)

Preparation

The child can sit or lie. Allow the child to handle the stethoscope. Listening to the parent’s or nurse’s heart or to their own hearts is often effective in dispelling anxieties in young patients. Ask the parent or child about heart disease in family members. Inquire whether the child has had difficulty in feeding (infant), undue fatigue, intolerance for exercise, poor weight gain, weakness, cyanosis, edema, dizziness, epistaxis, squatting, frequent respiratory tract infections, or delayed development. Ask the parent whether the mother had any infection or took medications during pregnancy, age of mother at infant’s birth, and presence of maternal diabetes or alcohol use. Inquire whether the child had problems at birth, such as low birth weight, prematurity, congenital infection, or respiratory difficulty. Inquire about temperament of the child and family responses to illness.

Assessment of Heart

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Inspection | |

| Observe the child’s body posture. | Clinical Alert |

| Squatting is seen in tetralogy of | |

| Fallot. | |

| Persistent slight hyperextension of the neck in infants can indicate hypoxia. | |

| Restlessness accompanied by abdominal pain, pallor, vomiting, unconsolable crying, and shock can indicate acute myocardial infarction in susceptible children. | |

| Observe the child for cyanosis, mottling, and edema. | Clinical Alert |

| Cyanosis, pallor, and mottling can indicate heart disease. Edema can indicate congestive heart failure. Edema of sacral and periorbital areas is more common in younger children. | |

| Edema of the extremities is more common in older children but in the younger child can more likely indicate renal failure. | |

| Cyanosis increases with crying in children with an atrioventricular canal defect and with some other cardiac defects. | |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Observe the child for signs of respiratory difficulty (grunting, costal retractions, flaring of the nares, adventitious chest sounds) and hacking cough. | Clinical Alert |

| Respiratory difficulties and congested cough can indicate congestive heart failure or respiratory infection. | |

| Inspect the child’s nailbeds for clubbing, lengthening, widening, and splinter hemorrhages (thin, black lines). | Clinical Alert |

| Clubbing indicates hypoxia. | |

| Splinter hemorrhages indicate emboli and might indicate bacterial endocarditis. | |

| Symmetric chest expansion is normal. | |

| In thin children the apical pulse, or point of maximal impulse (PMI), can be seen as a pulsation. | |

| Examine the anterior chest from an angle. | Clinical Alert |

| A sternal lift or heave can signal congestive heart failure. | |

| Observe for the symmetry of chest movement, visible pulsations, and diffuse lifts or heaves. | A systolic heave can indicate right ventricular enlargement. |

| Palpation | |

| Using the fingerpads, palpate the anterior chest for the apical pulse or PMI. The location of the PMI is usually felt at the apex of the heart and is found in the fourth intercostal space in children 7 years of age or younger and in the fifth intercostal space in children older than 7 years. | The apical pulse normally is palpable in infants and young children. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| A lower, more lateral PMI can indicate cardiac enlargement. | |

| An amplified PMI can indicate anemia, fever, or anxiety. | |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| The PMI is left of the midclavicular line until 4 years, midclavicular between 4 and 6 years, and to the right of the line by 7 years. | |

| Fingertips are more useful for detecting pulsations, and the ball of the hand (palmar surface at the base of the fingers) is useful for detecting vibratory thrills or precordial friction rubs. | Clinical Alert |

| Rubs and thrills are abnormal and should be reported. | |

| Thrills feel much like the belly of a purring cat. | |

| Percussion | |

| Percussion is used to estimate heart size by outlining cardiac borders. | |

| It is a difficult technique and has limited use-fulness in assessing the heart in infants and young children. | |

| The location of | |

| PMI is a more useful indicator of heart size. | |

| Auscultation | |

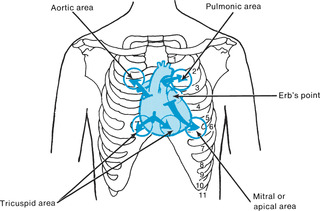

| Using both the bell (for low frequency; S3, S4 sounds) and the diaphragm (for high frequency; S1, | |

| S2 sounds), auscultate for heart sounds. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

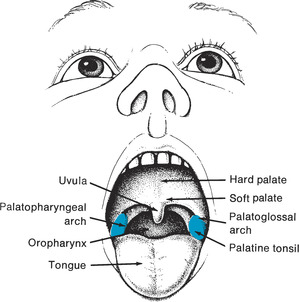

| Beginning in the second right intercostal space (aortic area), systematically move the stethoscope from the aortic to the pulmonic area (Figure 16-1). S2 is best heard at the base of the heart (aortic and pulmonic areas). Move down to Erb’s point, and then to the tricuspid and mitral areas. S1 is heard at the beginning of the apical pulse, which facilitates differentiation of S1 and S2. Evaluate the sounds for: | |

| Quality (normally S1 and S2 are clear and distinct) | S2 normally loudest in the aortic and pulmonic areas, near the base of the heart. S2 normally splits on inspiration in children and becomes single on expiration. |

| S1 and S2 are equal in intensity at Erb’s point. | |

| S1 is loudest in the mitral and tricuspid areas. | |

| Sinus arrhythmia is a normal variant in which the rate increases with inspiration and decreases with expiration. If unsure whether auscultation suggests sinus arrhythmia or a serious arrhythmia, ask the child to hold the breath. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| With sinus arrhythmia, holding the breath results in a steady heart rate. | |

| Pulse rate may be lower in athletic children and adolescents. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Heart sounds will be auscultated primarily on the right side of the chest if the child has dextrocardia. | |

| S1 is intensified during fever, exercise, and anemia. | |

| Accentuation of S1 can also indicate mitral stenosis. | |

| A split S2 that is fixed with the act of respiration can indicate an atrial septal defect. | |

| Pulse rate usually increases 8 to 10 beats for every degree of Fahrenheit increase. | |

| Rate (synchronous with radial pulse) | S1 that varies in intensity can indicate serious arrhythmia and must be reported. |

| Intensity (consistent with what would normally be found at each auscultatory point) | |

| Rhythm (normally regular) | |

| The child should be helped to assume at least two different positions during auscultation. If adventitious sounds are suspected, have the child assume sitting, standing, leaning forward, and left sidelying positions. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

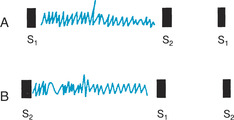

| Auscultate for additional sounds, such as S3 and and S4, which are best assessed with the infant or child lying on the left side. Assess for abnormal sounds such as clicks, murmurs, and precordial friction rubs. Murmurs should be evaluated and documented as to: | S3 is a normal finding. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Innocent or nonpathologic murmurs do not increase over time and do not affect the child’s growth (Table 16-2). Innocent murmurs are usually systolic (Figure 16-2), medium-pitched, and best heard at the second and third left interspaces. Innocent murmurs can disappear with changes in position and can be accentuated during fever, stress, or exercise. | |

| Location, or auscultatory area in which found. | |

| Timing in the S1-S2 cycle | |

| Intensity and whether intensity varies with the child’s position. Intensity is usually graded on a 6-point scale, with grade I being very faint and grade VI being audible even with the stethoscope off the chest. Grade III is considered moderately loud. PitchQuality (whether murmur is musical, blowing, or swishing) Precordial friction rubs are high-pitched grating or scratching sounds that are unaffected by breathing patterns. Pleural friction rubs stop when children hold their breath. | Organic murmurs are caused by congenital or acquired heart disease. Murmurs occurring before 3 years of age are usually related to congenital defects, and after 3 years to rheumatic heart disease. (Table 16-3) provides descriptions of murmurs associated with cardiac defects. Murmurs associated with rheumatic heart disease include those of aortic and mitral stenosis and of aortic and mitral regurgitation. Additional sounds and murmurs must always be described and reported for further evaluation. |

Assessment of vascular integrity is necessitated by cast application and by other conditions that can impair blood flow. Femoral and dorsal pedal areas should be palpated if cardiac defects are suspected.

| Adapted from Zator Estes ME: Health assessment & physical examination, ed 2, Clifton Park, 2002, Delmar Thomson Learning. | ||||

| Type of Murmur | Age | Intensity | Quality | Other Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary flow murmur (of the newborn) | Low–birth-weight newborn; disappears by 3 to 6 months of age | Grade I to IV (very faint to loud) | Rough | |

| Stills | >2 years | <Grade IV (loud) | Squeaking, twanging, musical | Best heard with child in supine position and with bell |

| Venous hum | 3 to 6 years | <Grade IV (loud) | Continuous hum | Heard best with child in upright position; disappears when supine and if head is turned |

| Pulmonary ejection | 8 to 14 years | <Grade IV (loud) | Slightly grating | |

| Defect | Location | Timing | Intensity | Pitch | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic stenosis | Right second interspace (aortic area) | Crescendo effect, occurring between S1 and S2 | Variable | Medium | Harsh |

| Pulmonic stenosis | Pulmonic area, third left interspace | Crescendo effect, occurring between S1 and S2 | Variable | Medium | Harsh |

| Mitral stenosis | Mitral area | Occurs between S2 and S1 | Variable (Grade I to IV); can be accentuated by exercise | Low | Rumbling |

| Aortic regurgitation | Aortic area | Heard between S2 and S1; usually a short period follows S2 before sound begins | Variable (Grade I to IV); most audible when child leans forward and exhales | High; best heard with diaphragm of stethoscope | Blowing Can be confused with breath sounds |

| Mitral regurgitation | Mitral area | Occurs between S1 and S2 | Variable; unaffected by respiratory cycle | High | Blowing |

| Ventricular septal defect | Left sternal border; third, fourth, and fifth interspaces | Heard between S1 and S2 | Very loud | High | Blowing |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | Second left interspace | Continuous; louder in late systole (just before S2); obscures S2; softer in diastole | Loud | Medium | Harsh, machinery like |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | Second and third left interspaces | Heard between S1 and S2 | Not well transmitted |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Palpate the peripheral arteries for rhythm and for pulse rate, using the same finger. Use the same fingerpads to palpate the pulses simultaneously for equality. | Normally pulses are palpable, equal in intensity, and even in rhythm. |

| Palpate the radial pulse. | |

| The radial pulse is best felt in children older than 2 years of age and who do not evidence spasticity. | |

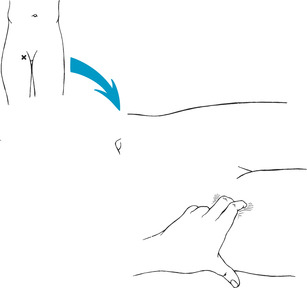

| Palpate the femoral pulse by applying deep palpation midway between the iliac crest and the symphysis pubis. | Clinical Alert |

| Diminution or absence of the femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, or posterior tibial pulses can indicate coarctation of the aorta. | |

| The child must be in the supine position (Figure 16-3). | A brachial-femoral lag is abnormal, when the two pulses are palpated simultaneously. |

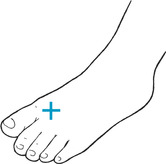

| Palpate the popliteal pulse by having the child flex the knee (Figure 16-4). Palpate the dorsalis pedis pulse along the upper medial aspect of the foot (Figure 16-5). Palpate the posterior tibial pulse posterior to the ankle on the medial aspect of the foot. |

Anxiety: related to change in health status.

|

| Figure 16-1Cardiac auscultatory areas.(From Hockenberry MJ et al: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 7, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

|

| Figure 16-2Timing of murmurs in S1-S2 cycle. A, Systolic murmur. B, Diastolic murmur. |

|

| Figure 16-3Femoral pulse.(From Potter PA: Pocket guide to health assessment, ed 3, St Louis, 1994, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

|

| Figure 16-4Popliteal pulse. |

|

| Figure 16-5Dorsalis pedis pulse. |

Altered family processes: related to shift in health status of family member.

Fluid volume excess: related to compromised regulatory system.

Altered growth and development: related to chronic illness.

Knowledge deficit: related to diet, drug therapy, signs and symptoms of complications.

Risk for impaired skin integrity: related to fluid excess.

Impaired social interaction: related to fatigue, limited mobility.

Activity intolerance: related to imbalance between oxygen supply/demand.

Sleep pattern disturbance: related to shortness of breath.

Altered tissue perfusion, cardiopulmonary: related to edema, weak or absent pulses, blood pressure changes in extremities.

Decreased cardiac output: related to physical illnesses/anomalies.

Fatigue: related to poor physical condition.

Impaired physical mobility: related to limited cardiovascular endurance.

Altered parenting: related to physical illness, presence of stress.

Social isolation: related to altered state of illness.

Risk for altered development: related to complexity of therapeutic regimen.