Chapter 47

Cardiovascular Manifestations of Connective Tissue Disorders and the Vasculitides

1. What is the leading cause of death in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and what are the most common cardiac manifestations of RA?

2. What are the cardiovascular manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)?

3. What are the cardiovascular consequences of NSAIDs with predominantly cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibition?

4. What is the major cardiovascular concern associated with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antagonists?

5. What are the clinical manifestations of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome?

Antiphospholipid antibodies (APLAs) promote intravascular clotting and can be found in primary APLA syndrome or secondary to other conditions, most commonly SLE. Clinical manifestations of APLA syndrome include spontaneous venous and arterial thromboses, strokes and neurologic syndromes, digital and extremity ischemia, livedo reticularis, thrombocytopenia, and recurrent spontaneous abortions. From a cardiac standpoint, acute coronary thromboses and diffuse small-vessel clotting resulting in global myocardial dysfunction have been described. In addition, Libman-Sacks endocarditis, defined by sterile vegetations on the mitral > aortic/tricuspid > pulmonary valves, is thought to arise from organization of thrombi and can cause valvular regurgitation or stenosis requiring surgical correction. Treatment for APLA syndrome is warfarin (goal international normalized ratio [INR] of 2.0-3.0) +/− daily low-dose aspirin, +/− hydroxychloroquine. Drugs associated with drug-induced lupus are given in Table 47-1.

TABLE. 47-1

DRUGS ASSOCIATED WITH DRUG-INDUCED LUPUS

| Drugs Definitively Known to Cause Drug-Induced Lupus | Cardiovascular Medications that Probably Cause Drug-Induced Lupus |

| Procainamide Hydralazine Diltiazem TNF-α antagonists Minocycline Chlorpromazine Quinidine D-Penicillamine Isoniazid Methyldopa Interferon-α |

β-Blockers Captopril Hydrochlorothiazide Amiodarone |

β-Blockers, Beta-adrenergic blocking agents; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

6. Describe the characteristic myocardial lesions of scleroderma and systemic sclerosis and their clinical manifestations.

7. What is the most common cardiac complication of scleroderma and systemic sclerosis?

8. What are the most common cardiac findings associated with the seronegative spondyloarthropathies?

9. Name the clinical manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), including the most common cardiovascular complications.

Polyarteritis nodosa is a nongranulomatous, patchy, necrotizing vasculitis of medium-sized muscular arteries. Constitutional symptoms (e.g., fever, malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, and weight loss) are common. Focal tissue ischemia and infarction can cause one of four cutaneous findings (painful subcutaneous nodules, non-blanching livedo reticularis, skin ulceration, or digital ischemia), asymmetric mononeuritis multiplex, hyperreninemic hypertension or renal insufficiency, or mesenteric infarction or aneurysmal rupture. Vasculitis in the distal coronary arteries cause recurrent, small myocardial infarctions (Fig. 47-1) that variably manifest as angina, acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or arrhythmias. Treatment for PAN is high-dose corticosteroids and cytotoxic therapy (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or methotrexate).

Figure 47-1 Numerous coronary artery aneurysms are present in this patient with polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). From Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, editors: Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders.

10. What are the most common findings in Takayasu arteritis and how should these patients be managed?

Takayasu arteritis is a granulomatous vasculitis of the aorta and its branches that is most common in young Asian women. Resultant arterial stenosis is much more common than aneurysm formation. Claudication, especially in the upper extremities, is the most common symptom. The most common findings include bruits, hypertension, and upper extremity blood pressure and pulse asymmetry. Aneurysms, when they occur, are most common in the aortic root and can cause significant aortic regurgitation (AR). Angiographic evaluation of the entire aorta and its primary branches, to determine the distribution and severity of vascular lesions, is recommended. When contraindications to angiography exist, magnetic resonance (MR) or computed tomographic (CT) angiography are acceptable alternatives. High-dose corticosteroids and anatomical correction of clinically significant lesions are the treatments of choice. Cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and anti-TNF agents are reserved for severe disease.

11. What are the most common cardiac manifestations of Kawasaki disease?

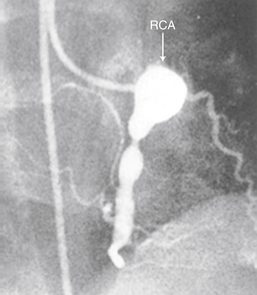

Kawasaki disease is an acute systemic febrile illness most common in infants and young children. Defining symptoms include high-spiking fever, cervical lymphadenopathy (nontender, greater than 1.5 cm in diameter, usually unilateral), erythematous and/or desquamative skin rash, and mucous membrane lesions (oropharyngeal injection, strawberry tongue, bilateral nonexudative conjunctivitis). Typical lab abnormalities include leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), and late thrombocytosis. Thrombosis of coronary artery aneurysms (especially those greater than 8 mm) is the most common cause of death. For this reason, serial echocardiography to evaluate coronary artery anatomy and other parameters is crucial. Treatment consists of high-dose aspirin and intravenous immune globulin. A coronary angiogram from a patient with Kawasaki disease is shown in Figure 47-2.

Figure 47-2 Coronary angiogram demonstrating giant aneurysm of the right coronary artery (RCA) in 6-year-old boy. (From Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al: Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics 114:1708-1733, 2004.)

12. What is the most common cardiovascular complications of Marfan syndrome (MFS)?

13. How should MFS be managed from a cardiovascular standpoint?

14. How is Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) type IV different from the other types?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Andrews, J., Mason, J.C. Takayasu’s arteritis—recent advances in imaging offer promise. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(1):6–15.

2. Antman, E.M., Bennett, J.S., Daugherty, A., et al. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;115(12):1634–1642.

3. Arnett, F.C., Willerson, J.T. Connective tissue diseases and the heart. In Willerson J.T., Cohn J.N., Wellens H.J.J., et al, eds.: Cardiovascular medicine, ed 3, London: Springer-Verlag, 2007.

4. Chung, E.S., Packer, M., Lo, K.H., et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial of infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure: results of the anti-TNF Therapy Against Congestive Heart Failure (ATTACH) trial. Circulation. 2003;107(25):3133–3140.

5. Levine, J.S., Branch, D.W., Rauch, J. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(10):752–763.

6. Mandell, B.F., Hoffman, G.S. Rheumatic diseases and the cardiovascular system. In Libby P., Bonow R., Mann D., et al, eds.: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2008.

7. Milewicz, D.M. Inherited disorders of connective tissue. In Willerson J.T., Cohn J.N., Wellens H.J.J., et al, eds.: Cardiovascular medicine, ed 3, London: Springer-Verlag, 2007.

8. Milewicz, D.M. Treatment of aortic disease in patients with Marfan syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:e150–e157.

9. Newburger, J.W., Takahashi, M., Gerber, M.A., et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease. Circulation. 2004;110:2747–2771.

10. Roman, M.J., Salmon, J.E. Cardiovascular manifestations of rheumatologic diseases. Circulation. 2007;116:2346–2355.

11. Sattar, N., McCarey, D.W., Capell, H., McInnes, I.B. Explaining how ‘‘high-grade’’ systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003;108:2957–2963.

12. Schur, P.H., Rose, B.D., Drug-Induced Lupus. Basow D.S., ed. UpToDate. UpToDate: Waltham, MA, 2013 Available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/drug-induced-lupus Accessed March 26, 2013

13. Stone, J.H. Polyarteritis nodosa. JAMA. 2002;288:1632–1639.