202 Cardiovascular and Neurologic Oncologic Emergencies

• Early symptoms of cardiac tamponade are tachypnea and dyspnea with exertion.

• The superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome is caused by obstruction of blood flow through the SVC by compression or vascular thrombosis.

• Headaches from brain tumors are often described as tension-type headaches, but more frequently they have associated nausea and are sometimes worse with body positioning that increases intracranial pressure (i.e., leaning forward).

• In patients with spinal cord compression from malignant disease, pain may precede neurologic changes by several weeks. At the time of presentation to the emergency department, some motor weakness is usually evident.

• Corticosteroids and radiation therapy are typical initial treatments for spinal cord compression from malignant disease.

Cardiovascular Oncologic Emergencies

Cardiac Tamponade

Epidemiology

Malignant cardiac involvement is common, occurring in 11% to 12% of patients with cancer. Of these patients, three fourths have epicardial involvement, and one third of these patients have a pericardial effusion.1 The most common malignant primary tumor that progresses to involve the pericardium is lung cancer. Breast cancer, gastrointestinal cancers, melanoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, and leukemia account for most other cases. These tumors invade the pericardium through direct or metastatic spread. Less commonly, malignant primary pericardial tumors such as mesothelioma and sarcoma or benign tumors such as angioma, fibroma, or teratoma may occur. In a study conducted from 1996 to 2005, malignant disease was the primary cause of medical cardiac tamponade (65%), followed by unknown causes (10%), viral disease (10%), and anticoagulant medication–related intrapericardial bleeding (3%).2

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Physical Findings

Patients with pericardial tamponade most commonly present with shortness of breath, hypotension, and often with clear lungs. Unfortunately, physical examination holds little value for diagnosing the presence of a pericardial effusion. However, as a malignant effusion becomes large enough to cause cardiac tamponade, some distinct physical findings may become evident. The Beck triad, first described in 1935, consists of increased jugular venous pressure, hypotension, and muffled heart sounds. However, this triad is most useful in acute cardiac tamponade, and it may be uncommon or difficult to assess in patients with atraumatic cardiac tamponade.3

Medical Decision Making and Diagnostic Testing

Electrocardiography

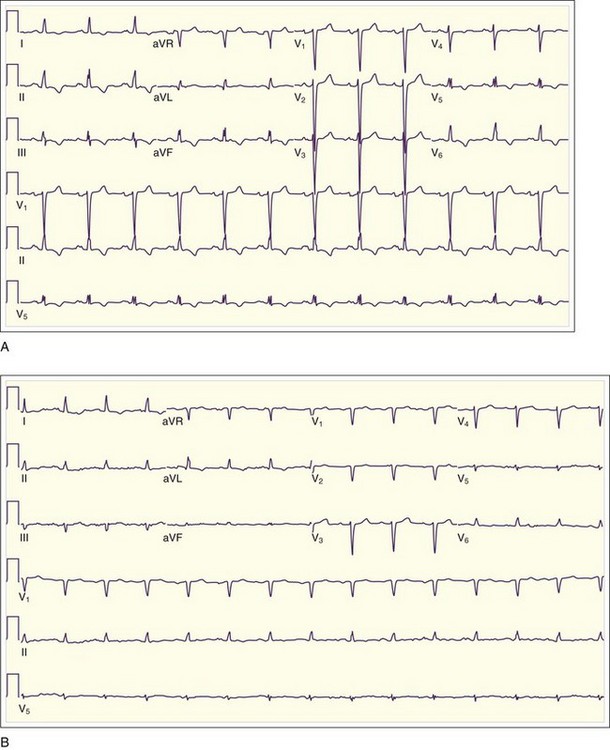

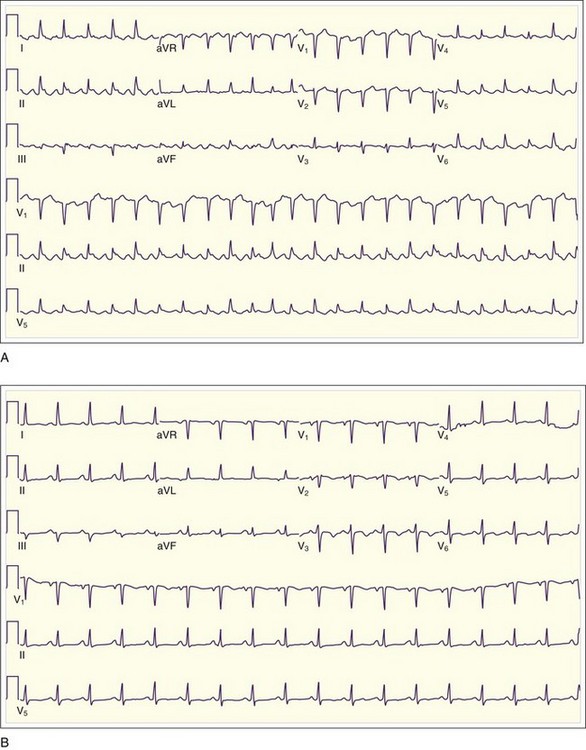

Low QRS voltage may be a sign of a large pericardial effusion, but it is more likely to be associated with tamponade physiology. In one small study, Bruch et al.4 studied 43 patients with a pericardial effusion. Of those patients, 14 of 23 with tamponade demonstrated low-voltage QRS complexes, as opposed to none of the 23 patients with effusion but without tamponade4 (Fig. 202.1). Electrical alternans (Fig. 202.2), demonstrated as beat-to-beat alterations in the amplitude of the QRS complex, is relatively specific but not very sensitive for cardiac tamponade. Electrical alternans may also rarely occur in patients with very large effusions without tamponade. Electrical alternans is caused by swinging of the heart in the pericardial effusion, and it generally disappears after removal of even modest amounts of pericardial fluid.

Chest Radiography

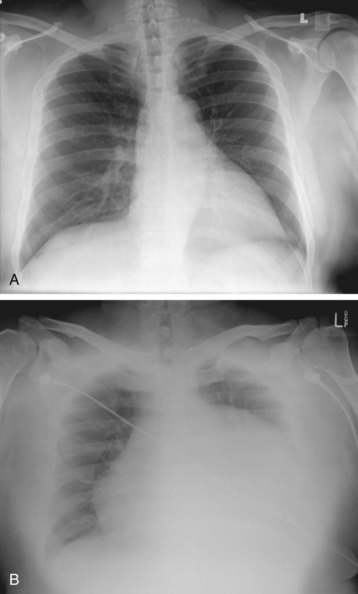

The typical finding on chest radiograph is an enlarged cardiac silhouette (the “water bottle”–shaped heart), as seen in Figure 202.3. In most cases, the lung fields are clear unless preexisting lung disease (e.g., malignant disease) is present. Cardiac tamponade may manifest without an enlarged cardiac silhouette if a small, rapidly accumulating effusion is the cause.

Echocardiography and Emergency Medicine Bedside Ultrasound

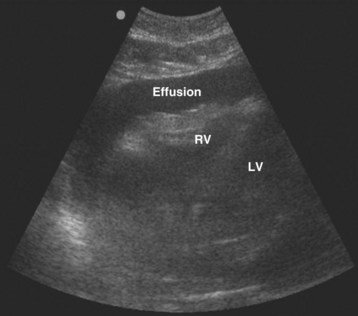

Echocardiography and emergency medicine bedside ultrasound play crucial roles in the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade. The first steps are to suspect a problem and to perform a screening cardiac ultrasound examination5 (Fig. 202.4).

Treatment

Pericardiocentesis may be performed under electrocardiographic or echocardiographic guidance. Echocardiographic guidance is preferred when available, because it allows greater precision of procedure direction and needle angle. Placement of an indwelling catheter is advisable, to prevent reaccumulation of fluid. The technique used for pericardiocentesis can be found in the “Tips and Tricks” box. Fluid obtained from pericardiocentesis should be sent for Gram stain, culture, acid-fast stain and culture, cytologic study, carcinoembryonic antigen determination, and polymerase chain reaction evaluation. Complications of pericardiocentesis are listed in Box 202.1.

Tips and Tricks

Technique for Pericardiocentesis Using Ultrasound Guidance

• Using bedside ultrasound, locate the ideal site of skin puncture where the largest fluid collection lies closest to the skin surface. This site is usually located on the left anterior chest wall. The clinician can choose either to mark the skin or to use the ultrasound device with a sterile sheath for dynamic guidance at this point.

• Prepare the skin in sterile fashion, and anesthetize the skin if time permits.

• Attach a 20-mL syringe to an 18-gauge spinal needle.

• Insert the needle at the site and trajectory determined by bedside ultrasonography. Take care to avoid the neurovascular bundle at the lower rib border and the internal mammary artery, which lies 3 to 5 cm lateral to the sternal border.

• Gently aspirate as the needle is advanced until fluid is obtained.

• Aspirate as much fluid as possible using the three-way stopcock.

• Alternately, use an over-the-needle catheter or the Seldinger technique if prolonged drainage is necessary. The Seldinger technique is performed using the same methods as outlined, but the clinician may use a thin-walled 18-gauge needle to pass a guidewire, followed by a catheter (e.g., a pigtail catheter) that may be left in place.

Disposition and Prognosis

Patients with cardiac tamponade are admitted to the hospital, typically in a cardiac care or intensive care unit (see the “Priority Actions” box). Emergency referral to cardiology for a pericardial window procedure is determined if the patient is hemodynamically stable for the procedure. Documenting the hemodynamic instability and emergency intervention is important (see the “Documentation” box). Initial in-hospital mortality is high for patients with malignant effusion and pericardial tamponade; the median survival is 150 days, and the 1-year mortality rate is 76.5%. This mortality results jointly from the underlying cancer and the cardiovascular compromise.2

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

• Consider malignant pericardial effusion in patients with a history of cancer who have tachypnea and dyspnea on exertion.

• Determine whether the patient has cardiac tamponade physiology by physical examination (i.e., Beck triad, pulsus paradoxus) or diagnostic evaluation (i.e., emergency bedside ultrasound).

• Perform an emergency pericardiocentesis or refer to cardiology for a pericardial window, based on hemodynamic instability.

• Assess for postprocedure reversal of tamponade physiology and for complications.

• Admit to a cardiac care or intensive care unit so that vital sign monitoring and follow-up diagnostics can be performed.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

• Vital signs, examination findings, and diagnostics supporting hemodynamic instability and cardiac tamponade physiology

• Informed consent for the emergency pericardiocentesis

• Postintervention assessment of vital signs, examination findings, or diagnostics to support therapeutic reversal of tamponade and improved patient clinical condition

• Code status to support the patient’s wishes given the underlying cancer history and invasiveness of the procedure

Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

Epidemiology

Currently, malignant disease is the cause of SVC syndrome in 85% of cases. Bronchogenic carcinomas account for most cases, and small cell and squamous cell carcinomas are far the most common causes. Although lung cancer is the leading cause of SVC syndrome, the overall incidence of SVC syndrome in patients with lung cancer is low, at 2% to 4%. The next most common malignant cause of the SVC syndrome is non-Hodgkin lymphoma because of its frequent presentation as a mediastinal mass. Metastatic cancers account for a small proportion of cases of SVC syndrome. Patients with SVC syndrome rarely experience immediately life-threatening complications in the absence of concurrent central airway obstruction.6,7

Pathophysiology

SVC syndrome is caused by one of several mechanisms. The first is direct compression by tumor or by enlarging lymph nodes (from inflammation or metastatic disease). The second is direct invasion of the SVC by tumor or other pathologic processes. The third is obstruction of the SVC by thrombus. Thrombus may additionally occur in up to 50% of patients with one of the other causes of SVC syndrome, and it may account for some treatment failures when therapy is directed at the underlying malignant disease.8 With compression of the SVC, the patient has increased resistance to venous blood flow, which is diverted through collateral venous networks.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The physical examination of the patient with SVC syndrome is often diagnostic. Most patients have facial edema or dilation of chest wall or neck veins. Some patients have cyanosis, arm edema, or plethora. A patient with the SVC syndrome who does not have visible upper body venous dilation is rare.9 An indwelling central venous device may be a clue to the diagnosis in thrombotic causes of SVC syndrome.

Dyspnea, one of the most common symptoms of SVC syndrome, occurs in more than half of patients. Patients may complain of fullness or swelling of the face, trunk, or upper extremities that may be exacerbated by positional changes such as bending over or lying down. Contrary to previous beliefs, catastrophic neurologic events appear to be quite rare.6,7 Findings of cerebral edema, laryngeal edema or upper airway stridor, or hemodynamic compromise represent the greatest emergencies.

Medical Decision Making and Diagnostic Testing

The initial test of choice when SVC syndrome is suspected is chest plain film radiography. Most of these radiographs are abnormal; one series found 84% of films to be abnormal. The most common abnormal findings were mediastinal widening in 64% (Fig. 202.5) and pleural effusion in 26%.9 A mass may also be seen in the superior mediastinum, right hilum or perihilum, or right upper lobe. Less commonly, right upper lobe collapse or rib notching may be apparent. However, a normal chest radiograph does not rule out the possibility of SVC syndrome.9

The next test is a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 202.6). CT defines the level and extent of blockage, provides detail on the amount of collateral flow, and is often able to identify the cause of obstruction. The presence of collateral vessels with compression of the SVC on CT is a reliable indicator of SVC syndrome, with a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 92%.10,11

Disposition and Prognosis

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

• Diagnose the SVC syndrome in a patient with lung cancer or lymphoma with head or neck swelling, engorged upper extremity veins, plethora, or dyspnea.

• Determine whether the patient has any emergency obstructive SVC syndrome findings of cerebral edema, airway obstruction, or hemodynamic compromise, and provide supportive measures and specialist consultation on an emergency basis.

Neurologic Oncologic Emergencies

Central Nervous System Emergencies

Epidemiology

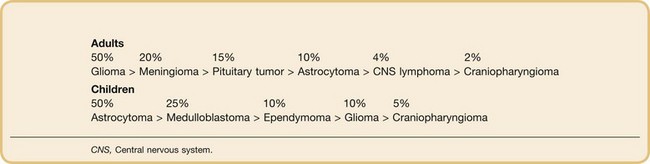

Although brain tumors account for only 2% of all tumors, they have significant sequelae. The 5-year survival rate of patients of all ages and all races who have malignant brain tumors is 33%; for children less than 14 years old, it is 62%; and for adults 65 years or older, it is 4.9%.12 In children, brain tumors are the most common solid malignant tumors and the second leading cause of cancer death after leukemia. Box 202.2 illustrates the differences in primary tumor types between adults and pediatric patients.

In general, a slight male predominance is seen in the incidence of malignant brain tumor. Whites have the highest incidence, with a descending incidence in Latinos and African Americans, and the lowest incidence in Native Americans and Asian Americans.12 The rising incidence of brain tumors in industrialized countries is thought to be mostly a result of environmental exposures and improved detection using diagnostic imaging.

Pathophysiology

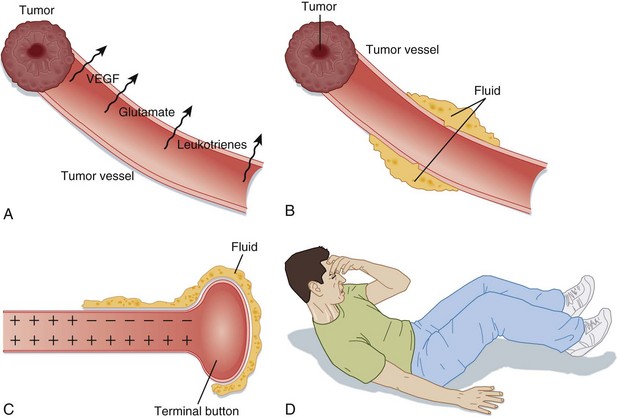

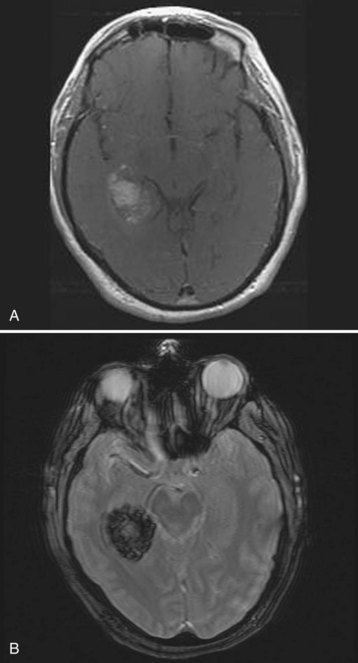

The pathogenesis of tumor-related neurologic dysfunction involves disruption of the blood-brain barrier leading to vasogenic edema. This condition is caused primarily by factors that increase the permeability of the tumor vessels (vascular endothelial growth factor, glutamate, and leukotrienes) and by the absence of tight endothelial cell junctions in tumor blood vessels. This process culminates in leakage of protein-rich fluid into the extracellular space, predominantly in the white matter of the brain. When this peritumoral edema begins to accumulate, the synaptic transmission can be disrupted and thus can lead to altered neuronal excitability and neurologic sequelae (Fig. 202.7). Vasogenic edema is what causes patients to suffer from headaches, nausea or vomiting, seizures, cognitive dysfunction, focal neurologic deficits, encephalopathy, or increased ICP leading to syncope or fatal herniation. Intratumoral hemorrhage, obstructive hydrocephalus, and tumor embolization can also have tumor-related consequences, but these entities are much less common than vasogenic edema.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Headache is the most common symptom of brain tumor, and headaches occur in approximately 40% to 50% of patients with primary or metastatic brain tumors. In one retrospective review, headaches were described variably, but most were described as tension-type headaches. The patients described the headaches as bifrontal and worsening ipsilateral to the lesion.13 Tumor-related headaches were differentiated from tension headaches by complaints of nausea and vomiting or especially by worsening of the headache with changes in body positioning that increased ICP (i.e., leaning forward). Worsening of the headache typically occurred following maneuvers that increase intrathoracic pressure, such as coughing, sneezing, or the Valsalva maneuver.

Seizure represents the most common presenting symptom of gliomas and cerebral metastases. In these tumor types, one study showed that seizure was the initial complaint in approximately 20% to 25% of patients.14 Patients who present with seizure activity usually have smaller primary tumors or fewer metastatic lesions in the brain compared with other presenting symptoms, because the seizure leads to earlier diagnostic imaging and diagnosis. Seizures can be generalized or focal, depending on the location in the brain of the tumor. Frontal lobe tumors may cause tonic-clonic movements in an extremity, and occipital lobe tumors may cause visual disturbances. Temporal lobe seizures may cause abrupt personality changes. Patients with a history of tumor-related seizures commonly present in a similar fashion on each visit, with or without a prodromal phase followed by a postictal period. If the seizures are generalized, the patient will be fatigued and sleepy; if the seizures are focal, however, the patient may have Todd paralysis.

Acute mental status change describes a deficit in cognitive function and is a presenting complaint in approximately 30% to 35% of patients with brain metastases.15 Cognitive dysfunction includes memory problems and mood or personality changes. Patients commonly present with fatigue, low energy, increased urge to sleep, and apathy toward daily activities.

Medical Decision Making and Diagnostic Testing

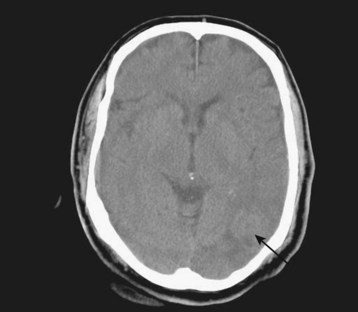

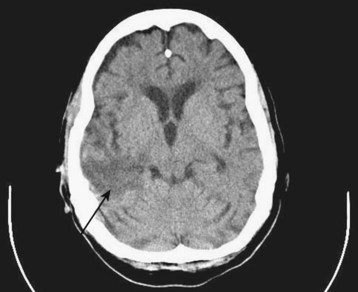

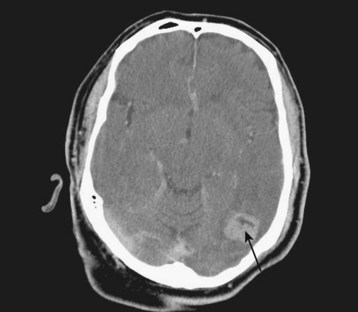

Diagnostic neuroimaging is the standard for confirming brain tumors and subsequent neurologic manifestations of oncologic emergencies. For the EP, CT scanning is the initial test of choice because of its speed and availability. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred study for primary and metastatic brain tumors, but it does not need to be performed on an emergency basis (Figs. 202.8 through 202.12).

Treatment

Tips and Tricks

Treatment Alternatives for Patients with Acute Vasogenic Edema

• Antiemetics (phenothiazine of choice or ondansetron for refractory vomiting)

• Euvolemia (0.9% normal saline solution)

• Euglycemia (80 to 120 mg/dL)

• Normal osmolarity (295 to 305 mOsm)

• Blood pressure control (CPP > 60 mm Hg and CPP < 120 mm Hg when ICP > 20 mm Hg)

• Ensure airway protection with intubation if necessary.

• Consider pretreatment with an agent to blunt increased ICP (e.g., 1.5 mg/kg lidocaine).

• Choose a sedative agent that does not increase ICP (e.g., etomidate 0.3 mg/kg or propofol 2 mg/kg).

• Consider a defasciculating dose of a nondepolarizing agent before a depolarizing agent (e.g., 0.01 mg/kg vecuronium before 1.5 mg/kg succinylcholine).

• Elevate the head of the bed to 30 degrees.

• Consider hyperventilation after discussion with a specialist (ensure PCO2 30 to 35 mm Hg).

• Consider antiseizure medication or barbiturate therapy (i.e., lorazepam, 2- to 5-mg bolus, or pentobarbital, 5-to 20-mg/kg bolus, then 1 to 4 mg/kg/hour).

Disposition and Prognosis

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

• Consider a central nervous system emergency in patients with a history of cancer who have mental status change, headache, cognitive dysfunction, seizure, syncope, or focal findings.

• Address life-threatening emergencies with prompt interventions (i.e., intubation to prevent anoxic brain injury; antiepileptic medications for status epilepticus).

• Prevent secondary brain injury by directing therapies to maintain oxygenation and perfusion of the brain and to reduce inflammation and neurologic sequelae of the tumor.

• Obtain prompt neurologic specialist input with the assistance of medical oncology for brain monitoring and admission management.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

• Fundus examination for evidence of papilledema

• Serial neurologic examinations to assess for a change in condition

• Continuous electroencephalographic monitoring for seizure activity (especially in intubated or paralyzed patient)

• Serial blood pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure measurements

• Time of neurologic consultant evaluation and recommendations and interventions

• Management to prevent secondary brain injury

• Code status to support the patient’s wishes given the underlying cancer history and neurologic outcome

Epidural Spinal Cord Compression

Epidemiology

Neoplastic ESCC is a common complication of metastatic cancer that has been documented to occur in 5% of patients with cancer.16 The most widely accepted definition of ESCC includes any radiographic indentation of the thecal sac. Although the cauda equina is not technically considered part of the spinal cord, the pathophysiology of compression of the cauda equina is the same as that of the spinal cord. Thus, compression of the thecal sac by malignant disease at this level is also referred to as ESCC.

The most common tumors are prostate, breast, and lung cancers (each accounting for 15% to 20% of all cases), which tend to metastasize to the vertebral column. Other important tumors are renal cell carcinoma, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and plasmacytoma, which make up most of the remaining cases. In children, the most common causes are sarcomas, neuroblastomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, Wilms tumor, and germ cell tumors. The most common vertebral levels of involvement for ESCC for all age groups are the thoracic spine (60% to 78%), followed by the lumbar spine (16% to 33%), followed by the cervical spine (4% to 15%); multiple levels are involved in up to 50% of patients.17 Delays in diagnosis and treatment remain common, and reports from multiple countries describe poor neurologic outcome in half or more of patients diagnosed with ESCC, including motor weakness, bladder dysfunction, and inability to ambulate.18–20

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The most common presenting symptom of ESCC is back pain, which occurs in more than 80% of patients.16 In general, pain precedes the onset of neurologic symptoms by several weeks. The pain is generally slowly progressive, although abrupt worsening of pain may signal a pathologic compression fracture. The pain may worsen with recumbency, movement, or the Valsalva maneuver, or it may develop a radicular quality. The radicular pain may be bilateral, especially in thoracic lesions.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Malignant Epidural Spinal Cord Compression Cautions for the Physician

• Back pain in a patient with prostate, lung, or breast cancer

• Repeat patient visits for accelerating back pain with risk factors for cancer without a plan for diagnostic imaging

• Not including ESCC in the differential diagnosis of a patient with urinary retention with risk factors for cancer

• Assuming that the ESCC is limited to the lumbar spine

• Not documenting a thorough neurologic examination, including strength, sensation, rectal tone, or reflex testing, in a patient suspected of malignant ESCC

Medical Decision Making and Diagnostic Testing

Although plain radiography is easily accessible in the ED and is able to predict ESCC in most patients with an evident lesion, it is still generally inadequate. Between 10% and 17% of patients have ESCC without findings on plain radiography.16

MRI and myelography (or CT myelography) remain the cornerstones of diagnosis of ESCC. MRI holds several advantages in that it is accurate, reliable, noninvasive, and able to image the entire thecal sac regardless of whether myelographic block is present (Fig. 202.13).

Disposition and Prognosis

![]() Documentation

Documentation

• Thorough neurologic examination, including motor, sensory, genitourinary (including rectal tone), and reflex testing

• Serial neurologic examinations to assess for a change in condition

• Time of neurologic consultant evaluation and recommendations and interventions

• Code status to support the patient’s wishes given the underlying cancer history and neurologic outcome

Cornily J, Pennec P, Castellant P, et al. Cardiac tamponade in medical patients: a 10-year follow up survey. Cardiology. 2008;111:197–201.

Forsyth PA, Posner JB. Headaches in patients with brain tumors: a study of 111 patients. Neurology. 1993;43:1678–1683.

Mandavia DP, Hoffner RJ, Mahaney K, Henderson SO. Bedside echocardiography by emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:377–382.

Sun H, Nemecek AN. Optimal management of malignant epidural spinal cord compression. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24:537–551.

Wan JF, Bezjak A. Superior vena cava syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24:501–513.

1 Klatt EC, Heitz DR. Cardiac metastases. Cancer. 1990;65:1456–1459.

2 Cornily J, Pennec P, Castellant P, et al. Cardiac tamponade in medical patients: a 10-year follow-up survey. Cardiology. 2008;111:197–201.

3 Guberman BA, Fowler NO, Engel PJ, et al. Cardiac tamponade in medical patients. Circulation. 1981;64:633–640.

4 Bruch C, Schmermund A, Dagres N, et al. Changes in QRS voltage in cardiac tamponade and pericardial effusion: reversibility after pericardiocentesis and after anti-inflammatory drug treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:219–226.

5 Mandavia DP, Hoffner RJ, Mahaney K, Henderson SO. Bedside echocardiography by emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:377–382.

6 Ahmann FR. A reassessment of the clinical implications of the superior vena caval syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 1984;8:961–969.

7 Schraufnagel DE, Hill R, Leech JA, et al. Superior vena caval obstruction: is it a medical emergency? Am J Med. 1981;70:1169–1174.

8 Davenport D, Ferree C, Blake D, et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of superior vena caval obstruction. Cancer. 1978;42:2600–2603.

9 Parish JM, Marschke RF, Dines DE, et al. Etiologic considerations in superior vena cava syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981;56:407–413.

10 Wan JF, Bezjak A. Superior vena cava syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24:501–513.

11 Kim HJ, Kim HS, Chung SH. CT diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome: importance of collateral vessels. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;37:363–366.

12 Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS). Primary brain tumors in the United States, 1997-2001: CBTRUS statistical report. Chicago: Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States; 2004.

13 Forsyth PA, Posner JB. Headaches in patients with brain tumors: a study of 111 patients. Neurology. 1993;43:1678–1683.

14 Coia LR, Aaronson N, Linggood R, et al. A report of the consensus workshop panel on the treatment of brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:223–227.

15 Clouston PD, DeAngelis LM, Posner JB. The spectrum of neurological disease in patients with systemic cancer. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:268–273.

16 Bach F, Larsen BH, Rohde K, et al. Metastatic spinal cord compression: occurrence, symptoms, clinical presentations, and prognosis in 398 patients with spinal cord compression. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1990;107:37–43.

17 Sun H, Nemecek AN. Optimal management of malignant epidural spinal cord compression. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24:537–551.

18 Husband DJ. Malignant spinal cord compression: prospective study of delays in referral and treatment. BMJ. 1998;317:18–21.

19 Helweg-Larsen S. Clinical outcome in metastatic spinal cord compression: a prospective study of 153 patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 1996;94:269–275.

20 Milross CG, Davies MA, Fisher R, et al. The efficacy of treatment for malignant spinal cord compression. Australas Radiol. 1997;41:137–142.